"[Arms Control Today] has become indispensable! I think it is the combination of the critical period we are in and the quality of the product. I found myself reading the May issue from cover to cover."

May 2022

Edition Date

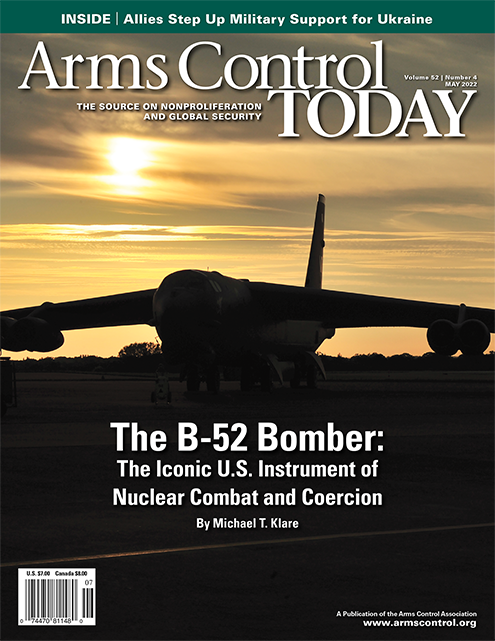

Cover Image

May 1, 2022

May 1, 2022

May 1, 2022

May 1, 2022

May 1, 2022

May 1, 2022

May 1, 2022

May 1, 2022

May 1, 2022

May 1, 2022

April 30, 2022