U.S. Shifts Arms Control Strategy with Russia

The Trump administration has softened its demand that China immediately participate in trilateral nuclear arms control talks with the United States and Russia and says it is now seeking an interim step of a politically binding framework with Moscow.

But the administration continues to reject Russia’s offer of a clean five-year extension of the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) and has said that President Trump will not consider an extension until several conditions are met.

According to Trump administration officials, the framework with Russia must cover all nuclear warheads, establish a verification regime suitable to that task, and be structured to include China in the future.

“We’re dealing with Russia right now on a nuclear arms pact,” said President Donald Trump Aug. 11. “They want to do it badly.”

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said Aug. 31 that the United States is in “detailed discussions with them [Russia] on an arms control agreement” and that he hopes Washington and Moscow can “get that done before the end of the year.”

Following talks from Aug. 17-18 in Vienna with Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov, U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Arms Control Marshall Billingslea pinned a potential extension of New START on Moscow fixing alleged verification flaws in the treaty and agreeing to the new framework.

“New START is a deeply flawed deal negotiated under the Obama-Biden administration,” said Billingslea during an Aug. 18 press briefing. “It has significant verification deficiencies.”

According to Billingslea, these deficiencies include the absence of sufficient exchanges of missile telemetry and the limited frequency of on-site inspections.

Rose Gottemoeller, chief U.S. negotiator for New START, addressed Billingslea’s comments regarding verification in May. She said that in the end, “the United States got what it wanted in the New START verification regime: streamlined inspection procedures at a sufficient level of detail to be effectively implemented.”

He said that he would recommend that Trump consider extending the treaty only “if we can fix” the flaws “and if we can address all warheads, and if we do so in a way that is extensible to China.”

“[I]f Russia would like to see that treaty [New START] extended, then it’s really on them to come back to us,” he said, citing a mandate from Trump. “The ball is now in Russia’s court.”

Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy Robert Soofer reiterated the administration’s position at a Sept. 2 discussion hosted by the Mitchell Institute.

“There are some conditions that have been laid out for a possible New START extension” that “will depend on how much progress we’re making with Russia,” said Soofer. “Now we are waiting to see if Russia has the political will now to come talk to us about it.”

Following the August talks, Ryabkov responded that Russia would not support an “extension at any cost.” He added that “any additions” to New START “would be impossible both for political and procedural reasons.”

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said Aug. 23 that “the Americans put forth conditions that are, frankly speaking, absolutely unrealistic, including the demand that China join the New START or some other similar treaty that will be signed in the future.” Moscow, he said, continues to support an unconditioned extension of the treaty.

National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien suggested Aug. 16 that Putin could visit the White House to seal a new bilateral arms control understanding. “We’d love to have Putin come here to sign a terrific arms control deal that protects Americans and protects Russians.” But Billingslea emphasized Aug. 18 that the two sides “remain far apart on a number of key issues.”

The Trump administration has not specified what it would be willing to put on the table to incentivize Russia’s agreement apart from consideration of an extension of New START.

Billingslea told Axios Aug. 21 that Russia raised “a range of issues with U.S. capabilities” in Vienna, but that Moscow’s non-nuclear concerns about, for example, U.S. missile defenses are not on the table as part of a possible framework deal.

Billingslea has offered few clues about how a new agreement should capture U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons that have never before been limited by arms control, such as shorter-range tactical nuclear warheads and warheads held by each country in reserve.

He hinted, however, that the preferred U.S. approach would not necessarily hinge on counting individual unconstrained warheads and that a new agreement might put a cap on, rather than reduce, such warheads.

“What we likely will see is a hybrid approach that would maintain limitations on the strategic systems but which would provide for a method of ensuring that the overall inventory of warheads writ large is static,” he said.

New START expires next February but can be extended by up to five years if the U.S. and Russian presidents agree to do so. The treaty caps the U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals at 1,550 deployed warheads and 700 deployed missiles and heavy bombers each.

On-site inspections under the treaty, which were suspended in March due to the coronavirus, have yet to resume, and the next meeting of the Bilateral Consultative Commission (BCC), the implementing body of the treaty, remains postponed.

“The United States is studying how and when to resume inspections and the BCC while mitigating the risk of COVID-19 to all U.S. and Russian personnel,” said a State Department spokesperson Sept. 16. “The United States continues to implement and abide by the New START Treaty.” —KINGSTON REIF and SHANNON BUGOS

NEW START

China Still Rejects Trilateral Arms Control Talks

While the United States continues to push China to join trilateral arms control talks with Russia, Beijing continues to refuse to do so and has indicated that it does not plan to do so in the future either.

“We have implored the Chinese to be part of our strategic dialogue,” said Secretary of State Mike Pompeo Sept. 2. “If the Chinese Communist Party is serious about participating on the global stage and being a nation of size and scale that is part of this community, then it has an obligation.”

“We’re not going to negotiate another bilateral arms control treaty,” said Billingslea Aug. 18. Any framework that the United States reaches with Russia, he continued, “will be the framework going forward that China will be expected to join.”

Billingslea claimed that many “countries have already called out the Chinese for their failure to negotiate with us in good faith, and that chorus of calls…would accelerate dramatically once we have created an architecture to control all nuclear weapons.”

But China remains unmoved. “It is our clear and consistent position that China has no intention to take part in a trilateral arms control negotiation with the U.S. and Russia,” Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian said Aug. 21.

China has pointed to the difference in the sizes of its nuclear arsenal as compared to those of the United States and Russia as a reason for it not to join talks.

China currently possesses a nuclear warhead arsenal in the low 200s, according to the annual report by the Defense Department on the country’s military power published Sept. 1.

While the Pentagon says that Beijing’s warhead stockpile “is projected to at least double in size as China expands and modernizes its nuclear forces,” China’s nuclear arsenal would still be far below that of the United States and Russia. The United States and Russia are each believed to have about 6,000 total nuclear warheads, including retired nuclear warheads awaiting dismantlement.

Russia continues to say that it will not force China to come to the table and that if a multilateral nuclear agreement is to be negotiated then nuclear-armed France and the United Kingdom must be part of it as well.

Support for New START Remains Strong

Foreign leaders and members of Congress have continued to voice strong support for an immediate five-year extension of New START.

“I welcome the recent talks between the United States and the Russian Federation in Vienna, and I strongly urge both sides to agree to move quickly to extend the Treaty by the full five years,” said UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres Sept. 15. An extension, he said, would “lay the ground for negotiations on new agreements, including with other nuclear-armed countries.”

“It is critical for global security that Russia and the U.S. extend the New START Treaty as quickly as possible,” said German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas Aug. 10. “This presents an opportunity to involve China in particular in the future, thereby strengthening the Non-Proliferation Treaty as a whole.”

In Congress, Sens. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.), Rand Paul (R-Ky.), and Susan Collins (R-Maine) wrote a Sept. 8 letter to President Trump urging him to extend New START.

“At this juncture it is unlikely significant changes to the New START treaty could be successfully negotiated, nor a new treaty ratified in the Senate, prior to the lapse of the current agreement,” they wrote. “The best course of action would be for the United States to extend the current treaty, allowing time to negotiate with Russia, as well as China, on the contours of a new agreement.”

Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) and 16 other Democratic senators introduced a resolution Aug. 6 also calling on Trump to immediately extend New START for another five years.

“While President Trump has eagerly ransacked a series of bedrock nonproliferation agreements, he should spare New START a similar fate,” said Markey in a press release. “Through a simple extension, he can credibly claim to have limited two new Russian strategic nuclear systems, the only systems that experts believe Moscow can deploy during the extension.”

CBO Weighs Cost of New START Expiration

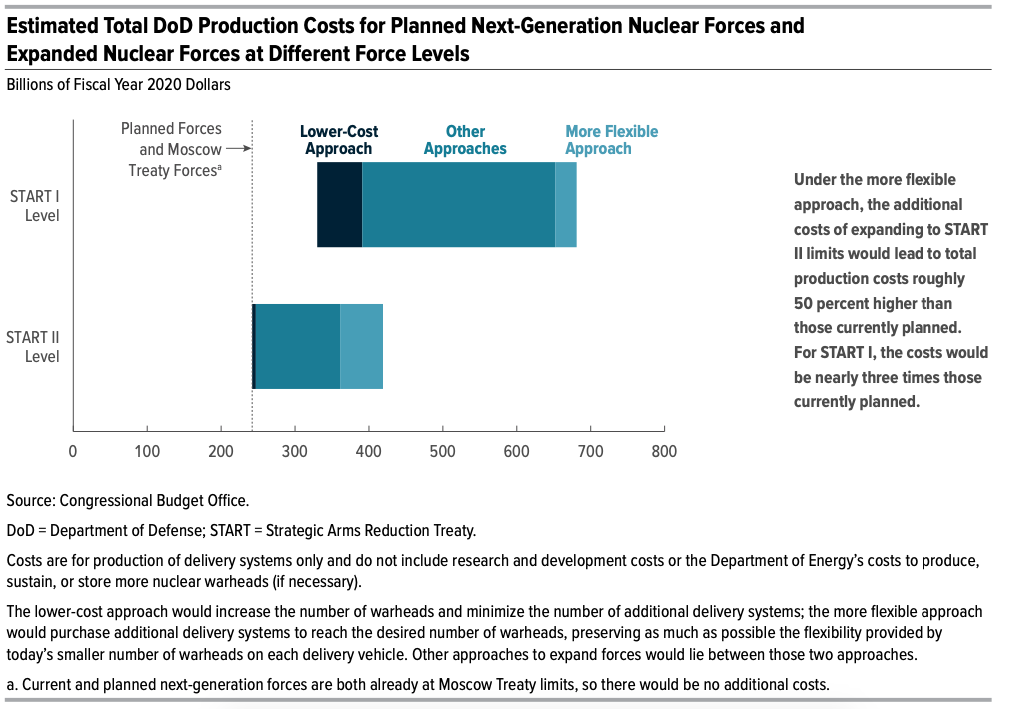

The potential expiration of New START with nothing to replace it could saddle the Defense Department with modest to staggeringly high costs if the United States decides to grow its deployed nuclear arsenal, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) found in an August report.

On the modest end, expanding forces to reach the limits set by the 2002 Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT), or the Moscow Treaty, would not increase the Pentagon’s cost relative to its current plans, since the New START limits are comparable to the SORT limits.

At the high end, the Pentagon could pay $410 billion to $439 billion as a one-time cost and $24 billion to $28 billion annually in pursuit of a more flexible approach that involves buying more delivery systems.

CBO estimated the cost if the United States increases its deployed strategic nuclear forces to the levels of three previous arms control treaties: SORT, which limited warheads to 1,700 to 2,200; START II, which sought to limit warheads to 3,000 to 3,500 but was never entered into force; and the 1991 START I treaty, which capped warheads at 6,000.

New START limits the United States and Russia to 1,550 deployed strategic warheads on 700 deployed strategic delivery vehicles. The Trump administration’s plans to sustain and modernize the U.S. nuclear arsenal are likely to exceed $1.5 trillion over the next several decades after including the impact of inflation.

CBO examined two approaches for expanding U.S. forces to reach each of the three treaties’ respective levels. The lower-cost and less flexible approach would involve increasing the number of warheads allocated to each missile and bomber and minimize any potential purchase of additional delivery systems. The more flexible yet more expensive approach would purchase more delivery systems to reach the number of desired warheads.

The United States could also take an approach that lies between those two approaches, CBO noted.

CBO said that the projected cost to increase the arsenal could be even higher, as the office’s estimates did not include the production of additional warheads by the Energy Department, any new operating bases or training facilities if needed, or an expansion in delivery system production capability.

Sen. Bob Menendez (D-N.J.), ranking member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.), chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, requested the report in September 2019. After the report’s release, the two released a statement calling for the extension of New START.

“The Trump administration’s unwillingness to continue the decades of strategic arms control by failing to extend the New START Treaty is driving the United States toward a dangerous arms race, which we cannot afford,” they said.

Following U.S.-Russian arms control talks in Vienna in mid-August, Lt. Gen. Thomas Bussiere, Deputy Commander of U.S. Strategic Command, said that the U.S. military is “agnostic” on the question of whether extending New START is in its best interests.

Bussiere added, “We do believe, however, that it [the treaty] does provide increased international security.”

INF TREATY

U.S. Seeking to Rapidly Deploy INF-Range Missiles

The United States is moving quickly to develop missiles formerly banned by the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, according to Trump administration officials. But questions remain about how it might use the missiles and where they would be based.

“Now that we are out of the INF Treaty, the department is making rapid progress to field ground-launched missiles,” said Deputy Defense Secretary David Norquist on Sept. 10 at the Defense News Conference.

Billingslea in August told Nikkei Asian Review, a Japanese news outlet, that the United States aims to talk with its allies in Asia about where to base such missiles.

The Trump administration wants to “engage in talks with our friends and allies in Asia over the immediate threat that the Chinese nuclear buildup poses, not just to the United States but to them, and the kinds of capabilities that we will need to defend the alliance in the future,” said Billingslea Aug. 15.

Billingslea specifically highlighted the ground-launched variant of the Tomahawk sea-launched cruise missile that the United States tested shortly after withdrawing from the INF Treaty in August 2019, reported Nikkei. Washington also tested an intermediate-range ballistic missile in December 2019.

The cruise missile is “exactly the kind of defensive capability that countries such as Japan will want and will need for the future,” said Billingslea.

Billingslea also emphasized that the United States should “get this capability from prototype to a deployed and deployable system, and then we will certainly want to have detailed discussions with all of our allies on the importance of being able to defend ourselves from threats and coercion and intimidation.”

In addition to the Tomahawk variant, General Joseph Martin, vice chief of staff of the Army, said that the Army is looking at developing a ground-launched version of the Standard Missile 6 (SM-6).

“We’re looking at land-based, land-launched Tomahawk missiles and SM-6s, which are in the Navy’s inventory,” to base on land as mid-range capabilities, said Martin Aug. 21.

The Marine Corps fiscal year 2021 budget request released in February included funding to purchase Tomahawk missiles, ostensibly for use as a ground-launched capability.

In October 2019, Taro Kono, Japan’s defense minister, downplayed the idea of Tokyo hosting INF-range missiles from the United States, saying that the two countries “have not been discussing any of it.” Australia and South Korea have also poured cold water on the prospect.

Both China and Russia responded to Billingslea’s remarks, saying they will respond if the United States deploys new ground-launched missiles.

“China firmly opposes U.S. plan to deploy land-based medium-range missiles in the Asia Pacific,” said Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian Aug. 21. “If the U.S. is bent on going down the wrong path, China is compelled to take necessary countermeasures to firmly safeguard its security interests.”

Russian Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova said Aug. 20 that “Undoubtedly, the deployment of new American missile systems in the region would provoke a dangerous new round of the arms race.” Such a move by Washington “would call for compensatory response measures,” she added.

Signed in 1987, the INF Treaty led to the elimination of 2,692 U.S. and Soviet Union nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers.

STRATEGIC STABILITY

Germany Calls U.S. Withdrawal from Open Skies “Wrong”

The Trump administration made the wrong decision to withdraw from the 1992 Open Skies Treaty, German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas said Aug. 10.

“There have…been shortcomings in Russia’s implementation of the Open Skies Treaty in recent years,” he said. “Nonetheless, we believe that the withdrawal by the U.S. is wrong.”

“Germany will continue to implement the Treaty on Open Skies and to do everything it can to preserve it,” he added.

Citing Russian compliance and implementation issues, the United States announced in May its intent to withdraw from the treaty, which will take place officially in November. Immediately after the U.S. announcement, Berlin signed onto a joint statement with 10 other European countries expressing regret over the decision. Maas’ recent remarks are a stronger denunciation of Washington’s move.

The 34 states-parties to the treaty met July 6 to discuss the way forward following the planned U.S. withdrawal in November.

One of the issues Washington cited for its withdrawal—Russia’s restriction on observation missions over Kaliningrad to no more than 500 kilometers—had been close to a resolution before the U.S. withdrawal, according to Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov.

“But now that the sides have approached mutually acceptable solutions on settling issues of flights over Kaliningrad, the U.S. has declared its withdrawal from the treaty,” said Lavrov Aug. 23. “This showed again that the U.S. decision to withdraw from the treaty is not linked with Russia’s actions. The Americans simply wanted to get rid of any instruments that limit their freedom of ‘maneuver.’”

Meanwhile, flights have resumed since their suspension March 1 due to the coronavirus pandemic. From Aug. 10-13, Russia conducted a flight over Germany, which included passing over Ramstein Air Base, a U.S. Air Force base; Spangdahlem Air Base, a NATO base; and U.S. troops in Bavaria.

Signed in 1992 and entered into force in 2002, the Open Skies Treaty permits each state-party to conduct short-notice, unarmed, observation flights over the others’ entire territories to collect data on military forces and activities. All imagery collected from overflights is then made available to any of the 34 states-parties.

FACT FILE

NEW RESOURCES & ANALYSES

- “Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the new nuclear danger,” by Daryl G. Kimball, The Hill, Aug. 5, 2020

- “We bombed Hiroshima, Nagasaki 75 years ago. Today, nuclear war still menaces,” by Lynn Rusten, USA Today, Aug. 6, 2020

- “It’s Time to Rethink Our Russia Policy,” by Rose Gottemoeller, Thomas Graham, Fiona Hill, Jon Huntsman Jr., Robert Legvold, and Thomas R. Pickering, Politico, Aug. 5, 2020

- “The New Nuclear Arms Race: The Outlook for Avoiding Catastrophe,” by Akshai Vikram, Ploughshares Fund, Aug. 6, 2020

- “The World Can Still Be Destroyed in a Flash,” by the Editorial Board, The New York Times, Aug. 6, 2020

- “New START: Why An Extension Is In America's National Interest,” by Zack Brown, The National Interest, Aug. 19, 2020

- “The U.S. Needs a Realistic Russia Strategy,” by the Editorial Board, Bloomberg, Aug 24, 2020

- “The Pentagon’s 2020 China Report,” by Hans Kristensen and Matt Korda, Federation of American Scientists, Sept. 1, 2020

- “Spinning good news on arms control,” by Steven Pifer, The Hill, Sept. 11, 2020

CALENDAR

| Sept. 15-30 | United Nations General Assembly, New York City |

| Sept. 21 | Deep Cuts Commission event, “After the demise of the INF Treaty: How to prevent a nuclear arms race in Europe.” RSVP here. |

| Sept. 26 | International Day for the Total Elimination of Nuclear Weapons |

| Oct. 2 | The high-level event to commemorate and promote the International Day for the Total Elimination of Nuclear Weapons will be held as a formal event of the UN General Assembly |

| Nov. 21-22 | G20 Summit, Riyadh |