Contact: Xiaodon Liang, senior policy analyst, [email protected]

As of 2024, the United States is currently replacing or modernizing nearly every component of its strategic nuclear forces. This modernization program, which will continue through the decade and into the next, will require at least $540 billion in acquisition costs. The new strategic delivery vehicles will cost an additional $430 billion to operate and maintain over their lifetimes. The National Nuclear Security Administration’s weapons activities will require an estimated $650 billion over the next 25 years. In total, the modernization of U.S. strategic forces will cost at least $1.5 trillion over their lifetime. The program includes:

- Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles

- Submarines (SSBNs) and Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs)

- Strategic Bombers, Cruise Missiles, and Gravity Bombs

- Nuclear Warhead and Pit Production Facilities

(In line with Department of Defense nomenclature, the term “acquisition costs” as used in this fact sheet includes research, development, test, and evaluation costs, procurement costs, and military construction costs. These are separate from the costs to operate and maintain weapons systems, and the costs of disposing them at the end of their lifetime. Together, these cost categories are referred to as lifecycle or lifetime costs.)

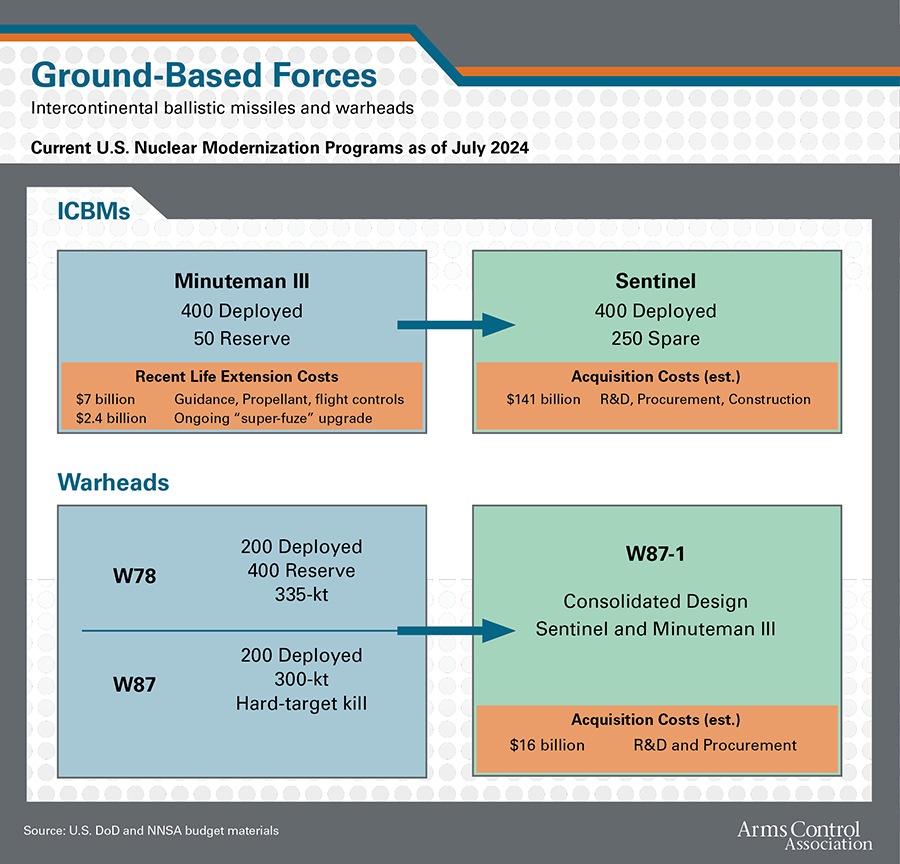

1. Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs)

The United States Air Force currently deploys about 400 Minuteman III ICBMs (as of September 1, 2022) located across three wings: the 90th Missile Wing at F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming; the 341st Missile Wing at Malmstrom Air Force Base in Montana; and the 91st Missile Wing at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota. U.S. nuclear-armed ICBMs are on high alert, meaning the missiles can be fired within minutes of a presidential decision to do so. Under New START, the United States maintains 50 extra missile silos in a “warm” reserve status.

Today’s Minuteman weapon system is the product of almost 40 years of continuous enhancement. The Pentagon spent more than $7 billion in the 2000s and 2010s on life extension efforts to keep the ICBMs safe, secure, and reliable through 2030. This modernization program has resulted in an essentially “new” missile, expanded targeting options, and improved accuracy and survivability.

Sentinel: Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent

The Air Force is replacing the Minuteman III missile, its supporting launch control facilities, and command and control infrastructure with a program known as the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD). The new ICBM, called the LGM-35A Sentinel, is supposed to meet an initial deployment target of May 2029 but may miss that date by two years. In line with the program delays, Congress eliminated procurement funding for the Sentinel in its 2024 appropriations bill and reassigned the funds to additional R&D.

As part of this program, the Air Force intends to purchase over 650 new missiles, 400 of which would be operationally deployed through the 2070s. The remaining missiles would be used for test flights and as spares. After Boeing withdrew its proposal from consideration in July 2019, the Air Force awarded a $13.3 billion development contract to the sole remaining bidder, Northrop Grumman, in September 2020.

The Sentinel has experienced substantial cost increases over the course of the missile’s development. Early estimates from August 2016 set expected program costs at $85 billion for the acquisition of the missile and $153 billion in life-cycle operations and sustainment costs. By October 2020, those cost estimates had increased to $96 billion and $168 billion, respectively.

In January 2024, the Air Force notified Congress that the program had triggered a critical breach of the Nunn-McCurdy Act, a cost-discipline provision of law. A subsequent mandatory review of the acquisition program determined that the new ICBM would cost $141 billion (in 2020 dollars) to acquire after minor revisions to lower costs. The Pentagon also confirmed that the program would be delayed by “several” years.

The W78, W87, and W87-1 ICBM Warheads

Minuteman III ICBMs are currently armed with one of two warheads, the 335-kiloton W78 or the 300-kiloton W87. The Minuteman ICBMs that are assigned the W78 can deliver up to three independently targetable warheads but are deployed with only one. The W87 is a newer design, originally paired with the now-retired Peacekeeper ICBM. The Air Force decided to reassign the W87 to the Minuteman III to retain the Peacekeeper’s higher accuracy and improved hard-target kill capability. Approximately 200 W87s were transferred. The latest Minuteman III modernization program involved replacing the warhead fuze on the W87s; this effort entered full-rate production in 2024 and is expected to have an overall R&D and procurement cost of $2.4 billion. The new fuze is believed to grant the Minuteman III an improved capability to destroy hardened missile silos by dynamically adjusting detonation height, taking missile accuracy into consideration.

In 2018, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), the autonomous Department of Energy agency responsible for building and maintaining nuclear weapons, abandoned a proposal for a common SLBM and ICBM warhead to focus solely on replacing the W78 with a new variant of the W87. This new warhead, the W87-1, will also be fielded on the Sentinel ICBM, and the NNSA projects it to cost $16 billion.

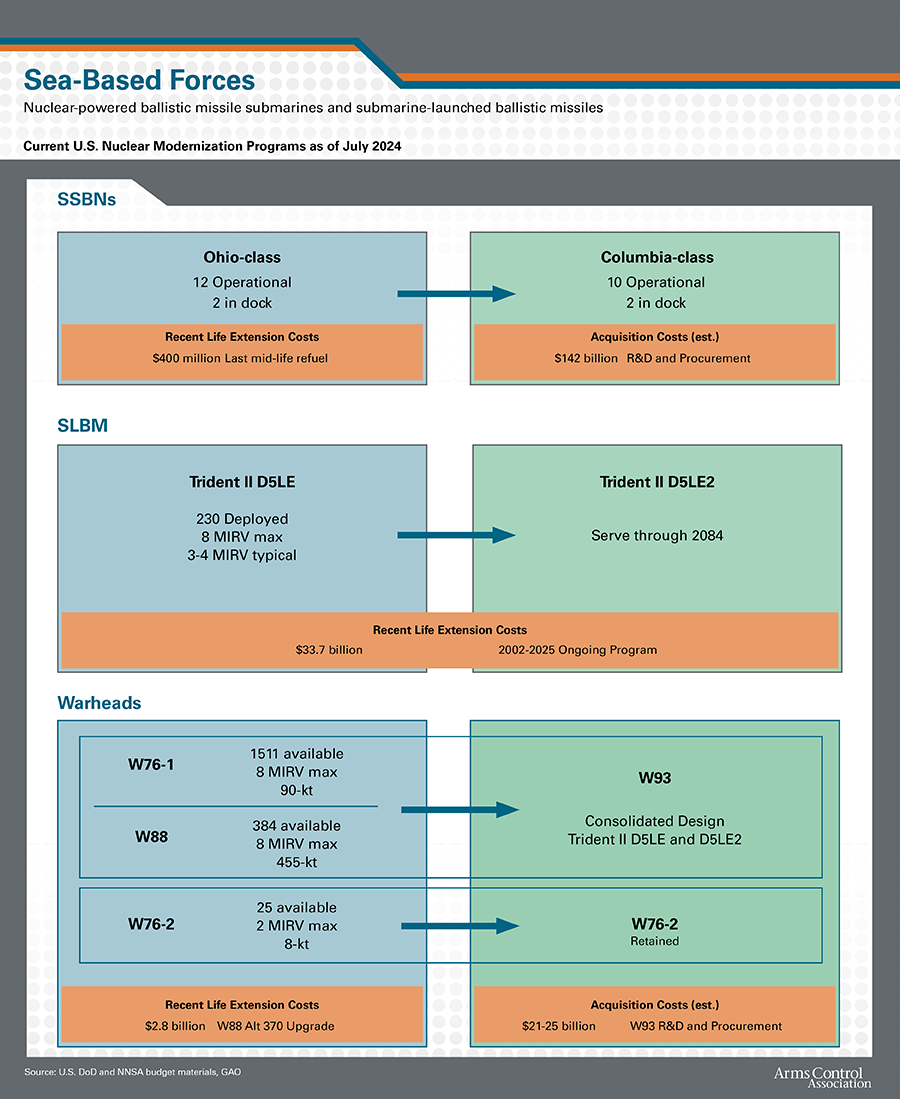

2. Submarines (SSBNs) and Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs)

The Navy deploys, as of September 1, 2022, 220 Trident II D5 SLBMs. The Navy operates a total fleet of 14 Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) based out of Bangor, Washington, (8 boats) and Kings Bay, Georgia (6 boats). Each boat is armed with 20 SLBMs, and eight to 10 boats are deployed at any time. The Ohio-class submarines have a service life of 42 years — two 19-year cycles with a four-year mid-life nuclear refueling. The cost of the last mid-life servicing of an Ohio-class boat, the USS Louisiana, was estimated at $400 million. The Ohio-class SSBNs were first deployed in 1981 and will reach the end of their planned service lifetimes at a rate of approximately one boat per year between 2027 and 2040.

The Navy plans to replace the Ohio-class starting in October 2030 with a new class of 12 ballistic missile submarines, now referred to as the Columbia-class. In 2012, the Pentagon projected that the lead boat in the class would begin its first deterrent patrol in 2031. The Navy disclosed in April 2024, however, that delivery of the first submarine—purchased in 2021—is likely to be delayed by 12 to 16 months. The Navy paid for a second boat in FY 2024 and plans to procure one each year from 2026 to 2035. The Navy has referred to the program as “the nation’s top defense acquisition priority.”

According to Defense Department estimates from 2017, the cost to develop and buy the submarines would be $128 billion in then-year dollars, with total life-cycle costs of $267 billion. In the president’s budget request for fiscal 2025, the Navy estimated that total procurement costs for the class would be $126 billion and that R&D would cost $5.7 billion through 2029, with further R&D expenses unknown. According to a Congressional Budget Office report from October 2023, the future cost of the Columbia class remains one of the most significant drivers of cost uncertainty for the future shipbuilding budget.

Trident II D5 Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles

First deployed in 1990, the force of Trident II D5 SLBMs has been successfully tested over 160 times since design completion in 1989 and is continuously evaluated. Each Trident ballistic missile can carry up to 8 warheads but normally carries an average of 4-5 warheads.

The Navy announced a first Trident II D5 life-extension program in 2002 that would modernize key components and allow the missile to serve aboard Columbia-class submarines until 2042. The first D5LE missiles were loaded onto submarines in 2017. The service announced in 2019 that it would pursue a second life-extension program (D5LE2) for the missiles to ensure they can operate for another 60 years, through 2084. The combined cost of the two life-extension programs is projected to be approximately $33.7 billion in R&D and procurement.

W76, W88, and W93 Warheads

The D5 SLBMs are armed with 1,511 W76-1, 25 W76-2, and 384 W88 warheads.

The W76-1 warhead has an estimated yield of 90-100 kilotons and completed a life-extension program in 2019 to lengthen its service life for an additional 30 years. The new W76-2 warhead, first proposed in the 2018 Nuclear Policy Review, has an estimated yield of 8 kilotons and was initially deployed at the end of 2019.

The W88 warhead entered the stockpile in 1989 and was recently life-extended. The NNSA intended to deliver the first production unit of the W88 Alt 370 life extension program—which replaces the arming, fuzing, and firing subsystem, refreshes the conventional high explosives within the weapon, and supports future life extension options—in 2020, but this did not occur until July 2021. The NNSA now believes it will deliver the last Alt 370 warhead in FY 2025.

The NNSA requested and received initial funding for a new W93 warhead (previously known as the “next Navy warhead”) in FY 2021. The Pentagon plans to have the new warhead eventually replace the W76-1 and W88 warheads on life-extended Trident II missiles. The Navy aims to also design a new reentry body, known as the MK7 aeroshell, to house the W93.

The NNSA believes the W93 program will enter its design definition stage in FY 2025 and plans to spend $456 million on the new warhead in that year. The MK7 aeroshell is still in the design definition stage as of 2024 and will cost $287 million in FY 2025. The costs of both the warhead and aeroshell are expected to increase significantly in the coming years, with projected R&D costs alone rising to more than $900 million each by FY 2029.

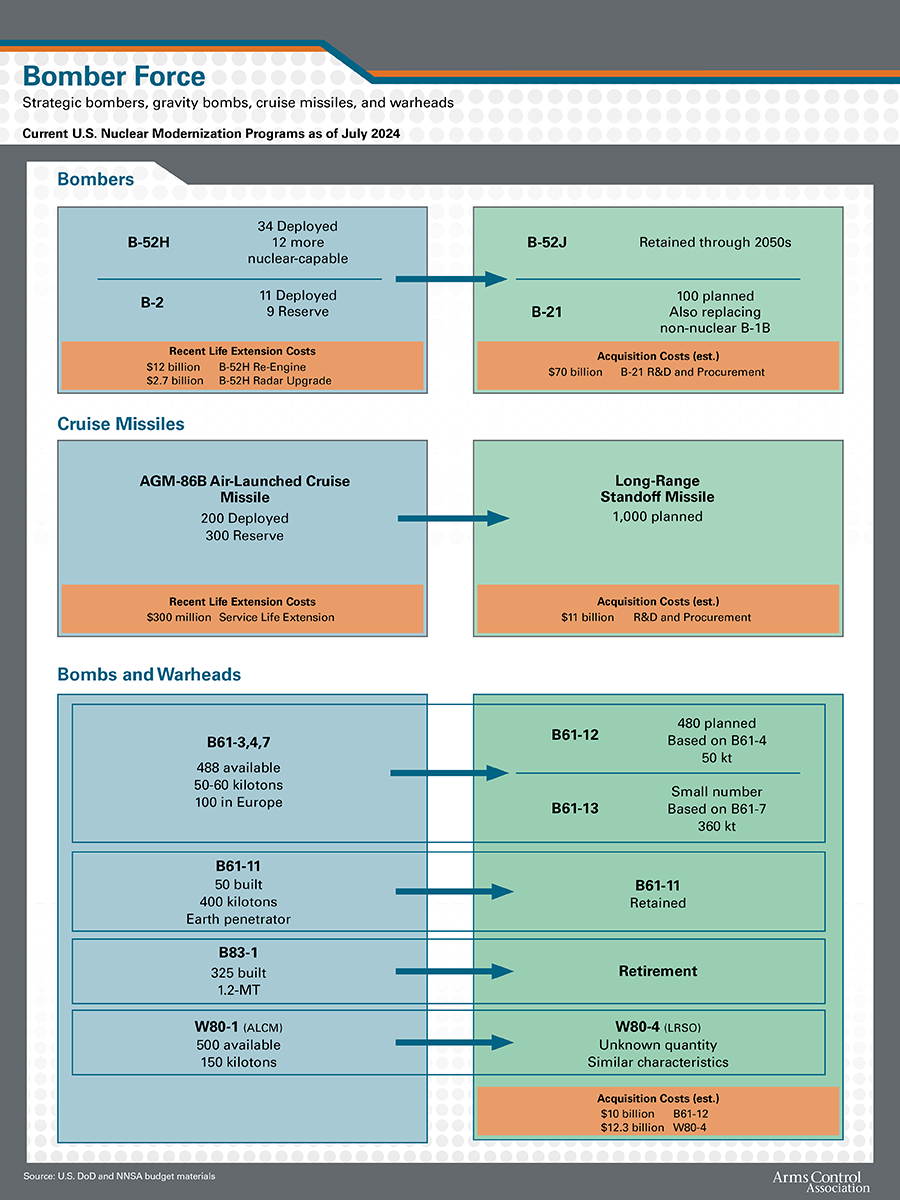

3. Strategic Bombers, Cruise Missiles, and Gravity Bombs

The United States Air Force operates a total fleet of 19 B-2 Spirit bombers at Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri and 46 nuclear-capable B-52H Stratofortress bombers at Minot Air Force Base, North Dakota, and Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. As of the September 2022 New START data exchange, 10 of the B-2s and 33 of the B-52Hs were deployed. In December 2022, one of 20 operational B-2 bombers was lost after it malfunctioned in flight and caught fire after landing, bringing the total fleet down to 19.

B-52H Bomber

First deployed in 1961, the B-52H fleet has undergone numerous modification programs, beginning in 1989, to incorporate updates to the bombers’ global positioning system and weapons-delivery capabilities. The bomber can now carry up to 2,000-pound munitions and a total of 70,000 pounds of mixed ordnance armaments. The B-52H is no longer assigned to carry nuclear gravity bombs and instead is armed with up to 20 air-launched cruise missiles for nuclear missions. The Air Force operates a total of 76 B-52H bombers, with 46 being nuclear-capable and the rest conventional.

The B-52Hs are currently being upgraded with AESA radar, new satellite communications systems, and modern engines. The Defense Department estimated in late 2021 that the engine overhaul would cost $12 billion dollars. Following the upgrade, the B-52s will be redesignated as B-52Js, and the Air Force expects them to remain in service through the 2050s.

B-2 Bomber

The Air Force continually modernizes the B-2 fleet, which first became operational in 1997 and is expected to last through 2058. In FY 2025, the Air Force requested more than $100 million to implement communications and avionics upgrades for the small fleet of bombers.

The B-2 can carry up to 16 nuclear gravity bombs, either the B61 or B83, but not cruise missiles. The bomber can also carry conventional weapons.

The Air Force announced in February 2018 that “once sufficient B-21 aircraft are operational, the B-1s and B-2s will be incrementally retired.” The B-1 bomber is no longer certified to perform nuclear missions.

B-21 Bomber

The Air Force is planning to purchase at least 100 new, dual-capable long-range penetrating bombers that are scheduled to enter service in 2025. The new bomber is known as the B-21 Raider. Much about this long-range bomber remains classified, including its speed, payload, stealthy characteristics, and production schedule. The Air Force awarded a contract to Northrop Grumman in October 2015 to begin developing the B-21 program. The new bomber conducted its first flight in November 2023, two years behind schedule.

The Pentagon set a cost ceiling of $550 million per aircraft in 2010, which is equal to roughly $700 million in 2023 taking into account inflation. In 2021, the Pentagon estimated 30-year total acquisition and operation costs for the new bomber program would reach $203 billion. Because of the secrecy surrounding the program, it is not possible to fully reconstruct ongoing costs. As of FY 2025, the lifetime unclassified R&D and procurement projections for the program total $41.2 billion, or only $412 million per plane – far below the $700 million target. Congress appropriated $8.2 billion for the program in fiscal 2024 and the president requested $8 billion in fiscal 2025.

Air-Launched Cruise Missile and Long-Range Standoff Cruise Missile

The B-52H carries the AGM-86 air-launched cruise missile (ALCM), first deployed in 1982. Each ALCM carries a W80-1 warhead, first produced in 1982.

As of 2023, the Air Force retains roughly 500 nuclear-capable ALCMs, of which about 200 are believed to be deployed at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota.

Some reports indicate that the reliability of the ALCM could be in jeopardy due to aging components that are becoming increasingly difficult to maintain. In recent years, the Air Force has spent roughly $300 million on a service life extension of the AGM-86.

The Air Force is developing the long-range standoff cruise missile (LRSO) to replace the AGM-86 by 2030. The new missile, the AGM-181, will be carried by B-52H bombers, as well as the new B-21. The first missile is slated to be produced in 2027, and the Air Force intends to purchase 1,000 in total. This new nuclear-capable missile will be armed with the refurbished W80-4 warhead.

The Air Force announced in April 2020 that Raytheon would be the sole contractor for the development of the LRSO and was awarded a $2 billion development contract in July 2021.

In 2016, the Pentagon projected the cost of the LRSO program to be about $11 billion (in then-year dollars). According to the fiscal 2025 budget request, the total acquisition cost of the program is now expected to be at least $16 billion. That does not include the cost of the W80-4 warhead, which is expected to cost an additional $12.3 billion.

B61 and B83 Gravity Bombs

The NNSA has consolidated variants of the B61 gravity bomb through a life-extension program that completed in December 2024. Before the program began, these variants included the B61-7 and B61-11, which are strategic weapons assigned to the B-2, and the B61-3 and B61-4, which are non-strategic weapons deployed in Europe. The B83-1 gravity bomb, a megaton-yield weapon that the Biden administration has sought to retire, remains in the stockpile, although funding for its maintenance has been reduced by the administration to minimal levels.

The B61 life-extension program, which the NNSA completed in December 2024, converted the -3, -4, and -7 variants of the bomb to a new B61-12 design. The NNSA’s independent Office of Cost Estimating and Program Evaluation told the GAO that its assessment of the program projected a total cost of approximately $10 billion. The first deployment of B61-12s to Europe likely took place in December 2022.

In 2023, the Biden administration announced it would build a new variant of the B61, the B61-13. The Pentagon says the new weapon will have a yield of roughly 360 kilotons and will provide options for targeting “harder and large-area” military targets. Previously, two older weapons, the B61-7 and the B83-1, with yields of roughly 360 kilotons and 1.2 megatons, respectively, were assigned this role. The B61-7 is currently being subsumed into the new B61-12 program, and the Biden administration has made clear its intention to retire the B83-1 despite some Congressional resistance. In FY 2024, the Biden administration requested a reduction in spending on maintaining the B83-1 of 47 percent, and Congress agreed to this change after the announcement of the B61-13.

U.S. nuclear gravity bombs can be deployed not only on the B-2 bomber, but also on allied and U.S. fighter aircraft. The F-16 and F-35 are flown by multiple NATO countries and therefore are certified both in the United States and in allied states to carry the B61 variants. In addition, the U.S. F-15E combat aircraft is also certified to carry B61 variants, including the B61-12.

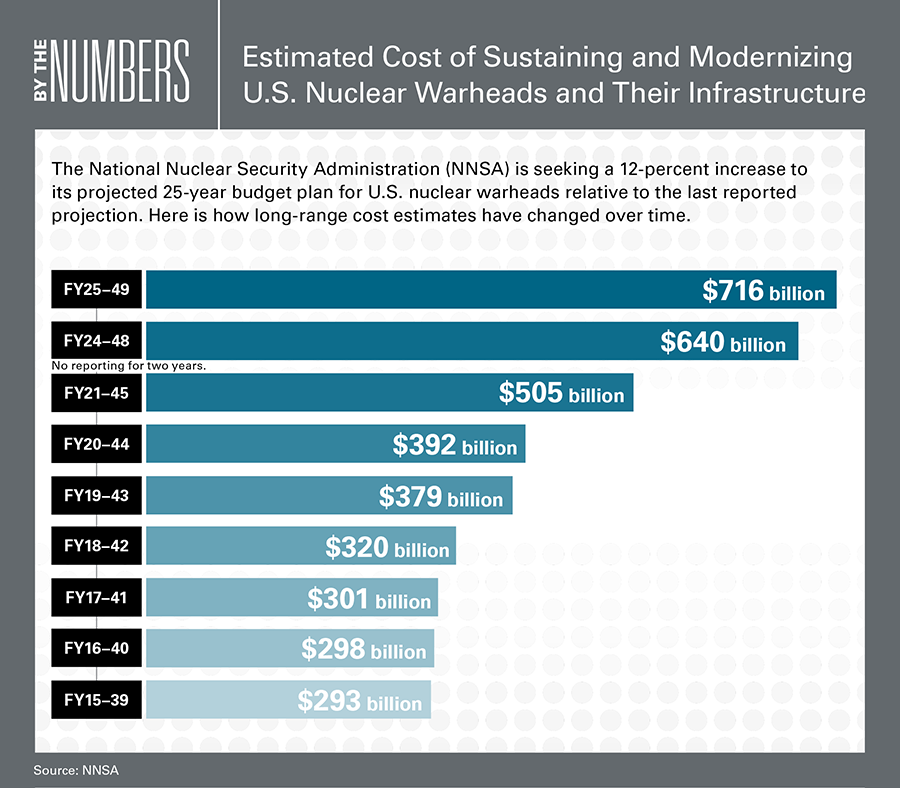

4. Nuclear Warhead and Pit Production Facilities

The NNSA is currently building or expanding several facilities to meet a nuclear bomb production target of 80 plutonium pits per year. Plutonium pits are the core of a thermonuclear device, often referred to as the ‘primary.’ The Savannah River Plutonium Reprocessing Facility, at which the NNSA intends to produce 50 pits per year, is likely to cost between $18 and $25 billion dollars, according to the latest administration estimate. Upgrades to the Los Alamos Pit Production Facility, where the other 30 pits per year will be assembled, will cost around $5.5 billion.

According to the NNSA’s budget request for fiscal year 2025, in addition to the construction costs of the two plutonium facilities, the agency will be spending another $4 billion annually from 2027 onward to produce pits at the sites. Weapons activities will cost roughly $716 billion dollars over the next 25 years, according to the NNSA’s own projections.

Other NNSA construction projects are also costly. The Uranium Processing Facility at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, which will handle and shape the enriched uranium for nuclear weapons and navy fuel reactors, is now expected to cost at least $9.5 billion. The nearby lithium facility has a $2.4 billion price tag. Both facilities will produce components used in the ‘secondary’ of a nuclear fusion weapon.