Fifteen years after it was signed by Russia and the United States, the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty is less than one month from expiring. Will the two countries start building up their arsenals again?

January/February 2026

By Xiaodon Liang and Daryl G. Kimball

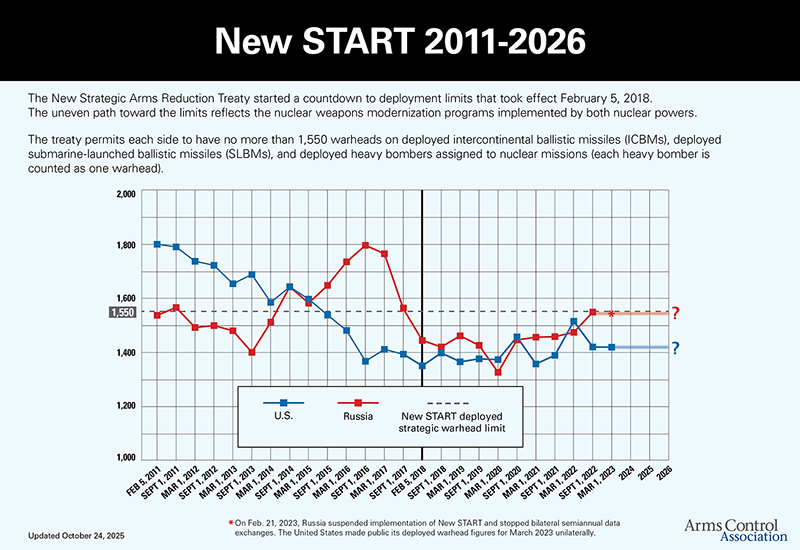

The United States and Russia have dramatically reduced their nuclear stockpiles since the end of the Cold War, thanks to a series of bilateral arms control agreements that have won the support of Republicans and Democrats alike. But with the expiration of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) set for Feb. 5, and no bilateral talks on further follow-on agreements to contain or cut U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals on the horizon, a new era of unconstrained global nuclear competition looms.

After nearly a year of negotiations, New START was signed by presidents Barack Obama and Dmitry Medvedev April 8, 2010. It capped accountable deployed strategic nuclear warheads and bombs at 1,550 and counted each heavy bomber as one warhead. These limits were approximately 30 percent below the 2,200-warhead limit set by the 2002 Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT), which did not include any new verification provisions.

New START also limited the two sides to no more than 700 deployed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and heavy bombers assigned to nuclear missions. Deployed and nondeployed ICBM launchers, SLBM launchers, and bombers were limited to 800. This additional cap restricted the ability for a “break out” of the treaty by preventing either side from retaining large numbers of non-deployed launchers and bombers.

New START was the first treaty to include provisions for directly counting the number of warheads on a missile. Inspectors were permitted, during short-notice inspections, to require the host country to allow for the counting of re-entry vehicles on an ICBM or SLBM.

The treaty did not constrain missile defense programs although its preamble acknowledges the “interrelationship between strategic offensive arms and strategic defensive arms” and that “current strategic defensive arms do not undermine the viability and effectiveness of the strategic offensive arms of the Parties.”

Given that the 1991 START treaty and its verification provisions expired Dec. 5, 2009, Russia and the United States were interested in re-establishing treaty-mandated verification mechanisms for New START. As General Kevin Chilton, commander of U.S. Strategic Command, testified to Congress in June 2010, “If we don’t get the treaty, [the Russians] are not constrained in their development of force structure and... we have no insight into what they’re doing. So, it’s the worst of both possible worlds.”

Upon signing New START, Obama said: “While the New START treaty is an important first step forward, it is just one step on a longer journey.” It was a prescient statement.

Senate ratification of the treaty was a struggle largely due to opposition from a bloc of senators led by Jon Kyl (R-Ariz.), who demanded a long-term plan and budget for modernizing the U.S. nuclear delivery systems and life-extending warheads. In November 2010, the Obama administration delivered revised estimates for funding National Nuclear Security Administration nuclear weapons complex programs totaling $85 billion for fiscal years 2012-2016, an average of $8.5 billion per year. Today, the NNSA weapons budget consumes $20 billion annually.

On December 22, 2010, following an eight-month-long process and eight days of often intense floor debate, a bipartisan Senate supermajority voted 71-26 in favor of ratification. Kyl still voted "no." The Russian State Duma and Federation Council completed the ratification process Jan. 26, 2011. The treaty entered into force Feb. 5, 2011, and both parties met the treaty’s central limits by the implementation deadline, Feb. 5, 2018.

Although New START modestly cut the U.S. and Russian strategic arsenals, it still left both with extraordinary firepower and further disarmament diplomacy to pursue. As Senator Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) noted in December 2010, New START “leaves our country [and Russia] with enough nuclear warheads to blow any attacker to Kingdom Come.”

However, since New START entered into force, Moscow and Washington have misfired on their on-again, off-again discussions on further nuclear reductions. In 2013, Russian President Vladimir Putin rebuffed an Obama initiative to engage in talks designed to achieve a further one-third reduction, and in 2020, U.S. and Russian negotiators resumed wide-ranging arms control talks but failed to reach any agreement.

With the original 10-year lifespan of the treaty about to expire, President Joe Biden and Putin agreed at the 11th hour, Feb. 3, 2021, to exercise the one-time, five-year extension allowed by Article XIV of the treaty. The move came after the first administration of President Donald Trump balked at extending New START with Russia, while seeking to engage China in a three-way arms control negotiation in 2020.

Following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia formally notified the United States Feb. 28, 2023, that it would suspend implementation of key New START provisions, including stockpile data exchanges and on-site inspections, which already were suspended temporarily in 2020 by mutual agreement due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Putin said Russia would not resume implementation unless the United States ended support for Ukraine and brought France and the United Kingdom into arms control talks. He later clarified that Russia would continue abiding by the treaty’s central limits.

In January 2025, the U.S. State Department said that, although “Russia [was] probably close to the deployed warhead limit during much of [2024] and may have exceeded the deployed warhead limit by a small number during portions of 2024,” the United States nonetheless “assesses with high confidence that Russia did not engage in any large-scale activity above the Treaty limits.”

With the final New START expiration date now approaching, Putin announced Sept. 22 that Russia is “prepared to continue observing the … central quantitative restrictions” of the treaty for one year after its expiration if the United States “acts in a similar spirit.” The proposal came in the context of talks on ending the conflict in Ukraine and vague statements by Trump that he wanted to maintain limits on nuclear arsenals.

In the absence of such an arrangement, each side will be free to upload additional warheads on existing land- and sea-based missiles, thus increasing their total strategic arsenals for the first time in decades. How the next chapter in the long-history of U.S.-Russian nuclear relations will unfold is yet to be determined.

The U.S. president said he would act “immediately” if Tehran takes steps to rebuild its nuclear program.

January/February 2026

By Kelsey Davenport

President Donald Trump said the United States will support new Israeli strikes against Iran’s missile program and threatened to take military action “immediately” if Tehran takes steps to rebuild its nuclear program.

Trump told reporters Dec. 29 that if Iran “will continue with the missiles,” the United States will support Israeli strikes and suggested that Tehran should make a deal with Washington to avoid further attacks.

Trump’s threats came during Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s Dec. 29 trip to visit the president at Mar-a-Lago. Before the trip, Israeli officials emphasized that Israel is ready to strike Iran again and suggested that Netanyahu would seek U.S. support for further military action during his visit.

Israel targeted the missile program during its 12-day air campaign against Iran in June, but Tehran was still able to conduct counterstrikes against Israel and the U.S. airbase in Qatar. (See ACT, July/August 2025.)

Since the conflict ended, Iran has announced steps to rebuild and expand its missile program, including equipping its missiles with new technologies. The commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, Major General Mohammad Pakpour, said Dec. 7 that Iran will incorporate stealth technologies into its systems so that they can better evade missile defenses, according to Iran’s state-run Press TV.

Trump’s Dec. 29 comments did not make clear what type of support his administration would provide if Israel strikes Iran’s missile program again, but he suggested that the United States would strike Iran directly if the country took certain steps to reconstitute nuclear activities.

Trump said that he heard that Iran is “trying to build up [its nuclear program] again.” If true, the United States will have “no choice but [to] very quickly eradicate that buildup,” he said.

Although it does not appear that Iran is restarting nuclear activities impacted by the U.S. and Israeli strikes in June, such as uranium enrichment, it is more challenging to assess the status of the country’s nuclear program while Tehran continues to prohibit International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspectors from accessing bombed sites.

Iran is legally obligated under the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) to implement safeguards on its nuclear program, but it suspended cooperation with the agency following the June attacks. Iran later allowed inspectors to return to sites that were not targeted, such as the Bushehr nuclear power plant, but has yet to provide the agency with reports about its nuclear materials or allow inspectors to access bombed facilities, arguing that safety and security concerns preclude cooperation. (See ACT, October 2025.)

In addition to suspending cooperation, Iran called for the IAEA to revise its safeguards approach to take into account the realities of armed conflict, as the agency continues to press Tehran to allow inspectors to visit nuclear facilities damaged by Israeli and U.S. military strikes.

Behrouz Kamalvandi, a spokesman for the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI), said Dec. 9 that after an attack, a country “cannot be expected to immediately allow inspectors into damaged sites, because that could mean handing sensitive information to its enemies.”

Iran has accused the IAEA of providing information used by Israel and the United States in the June strikes but presented no evidence to support those accusations.

IAEA Director-General Rafael Mariano Grossi said in a Dec. 20 interview with RIA Novosti, a Russian state news service, that the agency must assess for itself if Iran’s nuclear sites are unsafe or inaccessible due to the strikes. He reiterated Iran’s legal obligation to allow the IAEA access and said talks with Tehran are ongoing.

In November, the IAEA Board of Governors censured Iran for failing to implement its safeguards obligations and urged Tehran to cooperate with the agency. (See ACT, December 2025.)

Kamalvandi did not provide details about the changes Iran wants the IAEA to make, but he noted that the NPT and its safeguards provisions were drafted for “peaceful conditions,” and said that procedures and processes need to be revised to function under “wartime pressures” when there are unique security interests.

Despite suspending cooperation with the IAEA, Kamalvandi said that Iran remains committed to the NPT and its safeguards agreement.

Esmaeil Baghaei, the Iranian foreign ministry spokesman, reiterated Iran’s commitment to the NPT and said Dec. 22, at his weekly press briefing, that the issues raised by the IAEA require answers from the “parties responsible” for the current situation. Baghaei said that the “perpetrators of illegal and criminal attacks on these facilities” caused the interruption of monitoring.

China says it will maintain minimal nuclear capabilities but U.S. intelligence says China deployed ICBMs in one third of the silos at new missile bases.

January/February 2026

By Xiaodon Liang

China will maintain its nuclear capabilities “at the minimum level required for national security” while continuing a policy of no first use of nuclear weapons, a new policy statement claims, even as U.S. intelligence alleges the deployment of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) in a third of the silos at China’s new missile bases.

The restatement of Chinese policy came Nov. 27 in an official government white paper on arms control, disarmament, and nonproliferation. The paper is Beijing’s first comprehensive statement on these topics since open-source intelligence analysis identified a large-scale expansion of Chinese nuclear forces in 2021. (See ACT, September 2021).

But the document will disappoint those seeking an official acknowledgement by Beijing of its buildup or an explicit explanation of the logic behind its evolving force posture.

The paper comes close when blaming the United States for “reinforcing its nuclear deterrence and war-fighting capabilities” and “blurring the line between missile defense and strategic offense on purpose,” which constitute “severe threats” to strategic stability.

In response, China is improving “strategic early warning, command and control, missile penetration, and rapid response, as well as [nuclear forces’] survivability,” the document says.

This falls short of confirming a Pentagon claim, reiterated in this year’s edition of an annual report on China’s military, released Dec. 23, that China is making “progress on its attempts to achieve” an “early warning counterstrike” capability “where warning of a missile strike enables a counterstrike launch before an enemy first strike can detonate.”

The report reveals a previously unreported test launch by China of several ICBMs in “quick succession” in December 2024, “indicating the ability to rapidly launch multiple silo-based” missiles. The Pentagon previously noted a similar test in September 2023.

U.S. intelligence continues to assess that China may acquire a force of 1,000 operational nuclear warheads by 2030, the new report says. Although the Chinese white paper does not discuss quantitative requirements, it states that China “never has and never will engage in any nuclear arms race.”

The Pentagon report indicates that China’s strategic forces have deployed DF-31 solid-fueled ICBMs at some 100 silos in new missile fields in the northwest of China. The new missile fields, along with 30 new silos at older fields, add a total of 350 launchers to the land-based leg of China’s strategic arsenal, which also includes around 140 siloed liquid-fueled and road-mobile solid-fueled ICBMs, according to research by the Federation of American Scientists.

The U.S. report estimates that China’s total number of warheads remains in the low 600s, a similar finding to last year. (See ACT, January/February 2025.) U.S. intelligence assesses “a slower rate of [warhead] production when compared to previous years.”

China has renovated and expanded a pit production and warhead assembly site at Pingtong, Sichuan province, over the last few years, the Washington Post reported Dec. 28, citing imagery analysis by the Open Nuclear Network and the Verification Research, Training and Information Center.

The Pentagon report repeats allegations that China is seeking low-yield warheads, for “counterstrikes against military targets” and to “control nuclear escalation” which would enable China to “deter non-nuclear military actions with its nuclear forces.”

The Pentagon also assesses that “Beijing continues to demonstrate no appetite” for arms control talks.

Although the Chinese white paper endorses the “complete prohibition and thorough destruction” of nuclear weapons, it falls back on the traditional Chinese policy that countries possessing the largest nuclear arsenals—Russia and the United States—have a “special and primary” responsibility to reduce their forces first. Beijing has long relied on this formulation to justify avoiding substantive nuclear arms control efforts.

The paper also criticizes extended deterrence and nuclear sharing arrangements, drawing attention once again to China’s proposal for a no-first-use agreement among the five officially recognized nuclear powers (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States).

Of note in the document’s discussion of nonproliferation is the absence of a restatement of China’s support for the goal of denuclearizing the Korean peninsula. Chinese leader Xi Jinping also did not mention denuclearization during a meeting with his North Korean counterpart, Kim Jong Un, in September. (See ACT, October 2025.)

The white paper repeats previous criticism by Chinese officials of the agreement between Australia, the UK, and the United States (AUKUS) to transfer naval nuclear reactors and highly enriched uranium to Australia as part of a nuclear-powered submarine arms sale.

The AUKUS agreement “apparently runs counter to the object and purpose of the [nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty],” the new policy document says.

Congress is demanding annual briefings on the U.S. strategic posture, the indefinite deployment of no fewer than 400 “operationally available” ICBMs and a 2034 target for the nuclear-capable sea-launched cruise missile to reach initial operational capability.

January/February 2026

By Xiaodon Liang

The Republican-led U.S. Congress approved an annual defense policy bill that green lights $901 billion in discretionary spending and adds more than $2 billion to President Donald Trump’s request for expanded funding for nuclear weapons modernization and strategic missile defense.

The National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2026, which Trump signed into law Dec. 18, is supplemented by $118 billion in mandatory defense spending approved earlier this year in a budget reconciliation act. It contains various statutory changes relevant to U.S. nuclear forces and their acquisition, while demanding regular briefings on the president’s signature defense program, the “Golden Dome” missile defense system.

Congress will set final budget levels in appropriations bills for fiscal 2026, which remain trapped in negotiations among legislators on a tangle of domestic policy issues.

This year’s defense policy act, which emerged Dec. 7 from negotiations between the House and the Senate, is not as strident as its equivalent from last year in calling for steps to prepare for an arms race. But the legislation reiterates a demand in the fiscal 2025 act for annual briefings on implementation of the recommendations of the 2023 report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States, conditioning certain spending on the initiation of these briefings.

The commission report called for planning to upload additional warheads to U.S. intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), reconvert certain B-52H bombers for a nuclear role, and open missile tubes on Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines, while also acquiring more Long Range Standoff (LRSO) nuclear cruise missiles, B-21 bombers, and Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines, among other proposals to expand the nuclear force. (See ACT, November 2023.)

This year’s authorization act codifies a requirement that the United States indefinitely deploy no fewer than 400 “operationally available” ICBMs, with 150 launch facilities at each of the three current ICBM bases. This goes beyond a restriction that Congress has imposed in previous years barring the use of annually authorized funds to cut the number of ICBMs or reduce their level of readiness.

The act reflects congressional concern regarding the transition from the presently serving Minuteman III ICBM to the future Sentinel ICBM, which has experienced delays and a large cost-estimate increase. (See ACT, September 2024.) Although the Senate’s version of the policy bill had set a target date of 2033 for the Sentinel to reach initial operational capability, the final version of the act drops the deadline. A Nov. 10 article by the defense trade publication Inside Defense also reported that the service is working toward a late 2033 date.

The new ICBM, which the Air Force expects to cost $141 billion in 2020 dollars, will have an annual authorized budget of $5.3 billion, according to the final version of the defense legislation, $1.2 billion more than Trump requested. That total includes funds appropriated earlier this year in a budget reconciliation act. (See ACT, June 2025.)

Given the delay to Sentinel, which the Air Force had indicated would reach initial operational capability by May 2029, the problem of sustaining Minuteman III missiles has garnered increased attention. (See ACT, October 2025.) The act requires the Pentagon to provide an annual report on its strategy for sustaining the Minuteman III until the Sentinel fully replaces the older missile.

The legislation also authorizes an extra $210 million over the president’s budget and sets a 2034 target for the nuclear-capable sea-launched cruise missile to reach initial operational capability, while requiring that the Pentagon and National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) provide a “limited number … to meet combatant command requirements” by the end of September 2032.

The Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine program is authorized to spend a total of $11.9 billion across discretionary and reconciliation funding, $710 million more than the president requested.

Although the Senate proposed spending an extra $149 million this year to accelerate the LRSO air-launched nuclear cruise missile program, conference negotiators snubbed the idea. The Senate proposal had included $8 million for advance planning for a conventional variant of the LRSO. Total authorized spending on the missile could reach $1.05 billion in fiscal 2026.

The defense policy act makes several changes to the nuclear weapons enterprise and how it is managed. Statutes governing the Nuclear Weapons Council, a body of five senior Pentagon officials and the administrator of the NNSA, are modified to explicitly entrust the council with the responsibility for “developing options for adjusting the deterrence posture of the United States in response to evolving international security conditions.”

Although the council focused previously on setting priorities for NNSA that reflect Pentagon needs, this year’s statutory changes grant the council more authority to monitor nuclear delivery systems acquisition programs managed by the armed services, as well. The act would grant the council the power to “annually review the plans and budget” of the military departments, whereas previously it only reviewed those of the NNSA.

Last year, Congress modified a senior position within the Pentagon to create a central policy lead for nuclear weapons matters. That role, now titled the assistant secretary of defense for nuclear deterrence, chemical, and biological defense policy and programs, has been further augmented in this year’s defense act by specific instructions to the Pentagon to provide authorities and resources to the new office for overseeing relevant acquisition programs

On Dec. 18, the Senate confirmed Robert Kadlec, the Trump administration’s nominee for the position. Kadlec previously served in the George W. Bush and first Trump administrations as a health and biosecurity expert. As assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the Department of Health and Human Services, Kadlec was an early driver of the Trump administration’s efforts to identify and distribute a vaccine for the COVID-19 pandemic.

Within the NNSA itself, the act creates a rapid capabilities program to “develop new nuclear weapons or modified nuclear weapons that meet military requirements.” According to its new statutory basis, the program will “utilize non-traditional approaches,” adopt “tailored risk-acceptance processes,” “maximize reuse of existing components,” and take other steps to “carry out projects with the goal of achieving first production unit within 5 years of project initiation.”

According to the NNSA’s budget request for fiscal 2026, the agency already has set up rapid capabilities projects under the Stockpile Responsiveness Program “to execute at least two concurrent rapid development activities.”

The act also amends the statutory requirement that NNSA be able to produce 80 plutonium pits per year by specifying that 30 pits be produced at Los Alamos National Laboratories and 50 pits at the future Savannah River Plutonium Processing Facility. NNSA’s plans for pit production are the subject of an environmental impact assessment mandated by the outcome of a recent National Environmental Policy Act lawsuit. (See ACT, November 2024.)

NNSA is now only required to publish a report on the Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan each odd-numbered fiscal year, with Congress eliminating a requirement for shorter updates each even-numbered year.

The Trump administration’s proposal to expand U.S. missile defense capabilities, known as the Golden Dome program, receives wary approval in the defense policy act. The legislation codifies changes to the U.S. policy on missile defense, closely tracking the administration’s Jan. 27 executive order. (See ACT, March 2025.)

The new policy states that the government will “provide for the common defense of the United States and its citizens by deploying and maintaining a next-generation missile defense shield.” The act nullifies previous language that the United States would “rely on nuclear deterrence to address more sophisticated and larger quantity near-peer intercontinental missile threats,” an assurance that attempted to address concerns in Beijing and Moscow that an expanding U.S. missile defense architecture could undermine strategic stability.

Despite this endorsement of the goals of the Golden Dome, the defense committees expressed concern about the program’s viability in demanding that the Pentagon provide an annual report on the system in addition to quarterly briefings.

A number of countries say the missiles are needed to respond to rising fears of a conflict with Russia, the use of long-range strike missiles and drones in the Ukraine war and concern about U.S. reliability as a NATO partner.

January/February 2026

By Xiaodon Liang and Naomi Satoh

France has become the latest European nation to inaugurate a new medium-range missile program in response to rising fears of a conflict with Russia, the widespread use of long-range strike missiles in the Ukraine conflict, and—more recently—concern about the reliability of U.S. commitments to defend NATO allies.

After a group of European NATO states agreed in July 2024 to form a European Long-Range Strike Approach (ELSA) consortium to jointly develop missiles with ranges up to 2000 kilometers, several prospective medium-range projects have emerged. (See ACT, September 2024.)

France is taking the first steps toward acquiring a ground-launched medium-range ballistic missile that meets the ELSA range requirement, allocating 15.6 million euros toward initial risk analysis in the 2026 budget of the government of French Prime Minister Sébastien Lecornu. The budget plan, released in October but not yet passed into law, foresees an initial commitment of 1 billion euros over the next few years.

The missile will likely enter service around 2030, a report of the national defense and armed forces committee of the French National Assembly indicated in April. It is one of two exploratory French programs, the second being a range-extended version of a sea-launched land-attack cruise missile with an original design range of 1,000 kilometers. The parliamentary report noted that the French military had a preference for the ballistic option and a target range of more than 2,000 kilometers.

Germany and the United Kingdom also have announced plans to jointly develop a “new long-range strike capability with a range of over 2,000 km,” according to a May 15 press release. The missile, to be produced under the ELSA framework, will be “among the most advanced systems ever designed,” according to a July 17 statement by the UK embassy in Berlin. The partners aim to bring it into service “within a decade,” the embassy said.

Germany, meanwhile, is in talks with the United States to purchase ground-launched Tomahawk cruise missiles, with a range of at least 1,600 kilometers. (See ACT, September 2025.)

These medium-range missiles would grant NATO states the capability to hold at risk Russian targets up to the Urals. European officials view these weapons as a conventional warfighting tool, not a “pre-nuclear capability for deterrence or escalation management,” according to the authors of a Nov. 13 report by the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a UK think tank.

But it is not only the traditional conventional military powers of Europe that are interested in longer-range strike capabilities. The Netherlands, another ELSA participant, is seeking a domestic version of the Tomahawk, challenging local firms to produce prototypes in six months, said Gijs Tuinman, junior defense minister in the Dutch government responsible for arms procurement, in an Nov. 20 interview with BNR Nieuwsradio.

Other members of the ELSA consortium include Italy, Poland, and Sweden.

Russian forces continue to launch medium-range missiles against Ukrainian targets as the full-scale invasion approaches its four-year mark. Between August and October, Russian forces fired 9M729 cruise missiles 23 times, according to an unnamed Ukrainian official cited in an Oct. 31 Reuters report.

The 9M729 missile, which has an estimated range of 2,500 kilometers, was the center of U.S. accusations of Russian noncompliance with the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. (See ACT, January/February 2019.)

Russia also plans to deploy the Oreshnik intermediate-range ballistic missile on combat duty by the end of this year, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced in Dec. 17 comments to defense ministry officials. The missile was first used in combat last November. (See ACT, December 2024.)

An Oreshnik-equipped Russian strategic rocket forces unit assumed duties in Belarus Dec. 30, according to a video from the Russian Ministry of Defense.

The departure of five countries marks the largest number of exits from a humanitarian disarmament treaty.

January/February 2026

By Jeff Abramson

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania completed their withdrawal from the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Treaty in December and Finland and Poland will follow suit in early 2026, marking the largest number of exits from a humanitarian disarmament treaty.

Departing states claimed their decisions were in response to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

The 1997 Ottawa Convention, also known as the Mine Ban Treaty, outlaws the production, use, storage and transfer of victim-activated anti-personnel landmines worldwide. It entered into force in 1999 and, before the recent withdrawals, had 166 states-parties, with the Marshall Islands and Tonga joining last year.

UN officials and many delegations criticized the withdrawals at the annual meeting of Mine Ban Treaty states-parties held Dec. 1-5 in Geneva. The special envoy to the convention, Prince Mired Raad Zeid Al-Hussein of Jordan, warned that the treaty risks losing its “teeth” and called for stepping up collective efforts to universalize and fully implement it.

In a separate development, the Washington Post reported Dec. 19 that U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth issued a directive Dec. 2 for a forthcoming policy to allow for expanded use by the United States of weapons banned by the accord. This directive will essentially reverse the approach adopted during the Biden administration.

The withdrawals, although controversial, were expected as foreign ministers of the Baltic states and Poland recommended in a March joint statement that their countries should leave the treaty. (See ACT, April 2025.) In April, Finland’s prime minister made a similar statement, and between June 27 and August 20, all five countries deposited instruments of withdrawal, starting six-month clocks after which their exits could become official.

At the Geneva meeting, some delegations acknowledged the security concerns of the withdrawing states, while others emphasized the indiscriminate nature of the weapons and rejected any claimed military utility when compared to the human harm landmines cause. In the final report of the meeting, state-parties expressed “regret” over the withdrawals and said they “represent[ed] a setback and challenges in universalization efforts.”

After the report’s adoption, the New Zealand delegation, speaking on behalf of Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Panama, said that the final text was not strong enough on this point and did “not reflect the significant repercussions of these withdrawals for the Convention’s aims.”

Even more controversially, Ukraine, a state-party to the treaty, had communicated a decision to “suspend the operation” of the treaty in July. Ukraine did not attend the Geneva meeting, but states-parties rejected Kyiv’s action. In the final report, they affirmed that the treaty “does not allow the suspension of its operation and consequently its obligations” and called for “Ukraine … to further engage within the framework of the Convention.” The treaty does not have a provision for suspension and only allows withdrawal for countries not engaged in armed conflict.

In November and December 2024, under President Joe Biden, Washington announced it would provide treaty-prohibited anti-personnel landmines to Ukraine under a “limited exception” to its anti-transfer policy. (See ACT, December 2025.) It is unclear whether Trump has continued those transfers.

Hegseth’s Dec. 2 memo delivered another blow to the Mine Ban Treaty by rescinding the Biden administration’s more restrictive 2022 policy so that the United States may deploy landmines without geographic restriction and allow combatant commanders to decide where and when “non-persistent” (but still banned) landmines may be deployed.

Although President Bill Clinton in the 1990s was an early champion of a treaty banning landmines, the United States never joined the convention, arguing that such weapons were still needed on the Korean peninsula. As presidents have since gone back and forth as to whether to eventually join the treaty, the United States had refrained from transferring treaty-prohibited landmines except to Ukraine in 2024, did not use them except in one isolated incident Afghanistan in 2002, did not produce new landmines, and was the global leader in funding humanitarian demining.

Trump’s policy will further complicate global anti-landmine efforts, as will plans by Finland, Lithuania, and Poland to begin new landmine production after their withdrawals are finalized.

A French news organization found that army forces dropped barrels of chlorine from the sky in an attempt to recapture the al-Jaili refinery near Khartoum from the Rapid Support Forces militia.

January/February 2026

By Daryl G. Kimball

A months-long investigation by the France 24 news organization found strong evidence of the use of chlorine gas as a chemical weapon near the al-Jaili refinery, north of the Sudanese capital Khartoum, by the Sudanese Army Forces Sept. 5 and 13, 2024.

When used as a weapon, chlorine is a choking agent that can cause severe respiratory issues, lung damage, and death. Its use as a weapon is prohibited by the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC).

According to the investigation by France 24, published Oct. 29 in cooperation with C4ADS, a nonprofit organization with a mission to defeat the illicit networks that threaten global peace and security, army forces dropped barrels containing chlorine gas from the sky in their attempt to recapture the refinery from the Rapid Support Forces militia, their opponents in the brutal and ongoing civil war.

The use of chemical weapons represents a new low in a conflict in which both sides have been accused of commiting war crimes on a wide scale. The army is the only armed group in Sudan with the aerial military capacity to carry out such attacks. Similar tactics were employed by the military forces of former dictator Bashar al-Assad during the civil war in Syria.

On Jan. 16, 2025, the United States under the Biden administration sanctioned Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, commander of the army and Sudan’s de facto head of state, alleging that the army had used chemical weapons, but did not publish any evidence for the claim.

On April 24, the U.S. Department of State announced that it had determined that the Sudanese government used chemical weapons in 2024, triggering the imposition of sanctions, including restrictions on U.S. exports to Sudan and on access to U.S. government lines of credit.

Sudan’s ministry of foreign affairs denied the allegations and complained that the United States did not raise the issue through the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) as required. Both countries are members of the CWC and Sudan serves on the OPCW Executive Council.

The France 24 investigation traced documents showing that an Indian company, Chemtrade International Corporation, exported the chlorine to Sudan. Chemtrade told France 24 that the Sudanese importer assured them that the chlorine would be used “only to treat potable water,” which is an important civilian use for this product in Sudan where clean water is scarce. It is estimated that 17 million people in Sudan do not have access to safe drinking water, which has exacerbated disease outbreaks. During the course of the war, the rebel militia has destroyed water treatment facilities and power plants.

On Nov. 29, Sudan’s pro-democracy Civil Democratic Alliance for Revolutionary Forces demanded an immediate investigation by the OPCW into reports that the army has used chemical weapons.

Trump on New START: ‘If It Expires, It Expires’

January/February 2026

U.S. President Donald Trump has asserted a noncommittal attitude toward the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which expires Feb. 5.

“If it expires, it expires. We’ll just do a better agreement,” he said in a wide-ranging interview with The New York Times published Jan 8. “You probably want to get a couple of other players involved also.”

The new comments suggest Trump would allow the last U.S.-Russia strategic arms control treaty to lapse without accepting a formal offer from Russian President Vladimir Putin to continue to respect the central limits of the agreement for one year if the United States also agreed to do so. When asked by a reporter Oct. 5 what he thought of Putin’s proposal, Trump said it “sounds like a good idea to me,” but the White House has not formally responded to the Kremlin offer.

Trump’s Jan. 8 remarks to the Times about the expiration of New START stand in contrast with comments he made in July when he said, “We are starting to work on that.… That is a big problem for the world, when you take off nuclear restrictions.”

Since taking office last January, his administration has neither outlined a strategy for negotiating a new nuclear arms control agreement with Russia nor outlined how it would bring China into nuclear risk reduction or arms control talks.—DARYL G. KIMBALL

IAEA Raises Concerns About Safety at Chernobyl

January/February 2026

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) concluded that a drone strike last February compromised nuclear safety at the mothballed Chernobyl nuclear complex after a visit to the Ukrainian site in November.

The IAEA conducted a comprehensive safety assessment at Chernobyl at the request of Ukraine’s nuclear regulator. The objective of the mission was to evaluate the status of the containment structure built in 2016 to prevent further radioactive release at a reactor unit destroyed in the infamous 1986 accident. The structure, known as the new safe confinement structure, was struck by a drone in February 2025. The strike caused a fire in the outer cladding of the structure but did not result in the release of radiation, according to the IAEA.

However, the agency’s November assessment suggests that, without repairs, the structure is at risk. IAEA Director-General Rafael Mariano Grossi said Dec. 5 that the agency concluded that the containment structure “lost its primary safety functions” due to the strike, but “there was no permanent damage to its load-bearing structures or monitoring systems.”

Grossi said there were limited repairs to the roof of the structure, but “timely and comprehensive restoration remains essential to prevent further degradation.”

The Dec. 5 statement said that there will be additional repairs on the structure in 2026 to “support the re-establishment of [its] confinement function.”—KELSEY DAVENPORT

OPCW Names New Director-General

Janyuary/February 2026

Sabrina Dallafior of Switzerland was chosen the next director-general of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) by the states-parties Nov. 27. She is the first woman appointed to the four-year position, which begins July 2026.

“As Director-General, I will accord the highest importance to upholding the norm against chemical weapons. Ensuring its long-term sustainability requires us to investigate all credible allegations of use, establishing the scientific facts, and to denounce all confirmed cases […] This is non-negotiable, as it touches the very core of the [Chemical Weapons] Convention,” Dallafior said in a statement released by the OPCW.

Currently, Dallafior is the Swiss ambassador to Finland. She has been a career diplomat since 2000 and has extensive multilateral experience regarding security and defense policy, disarmament, arms control, and nonproliferation.

Dallafior will succeed Fernando Arias, who has served as the fourth director-general since 2017. Under Arias, the OPCW has taken on investigations of chemical weapons use by the former government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and the illegal use of riot-control agents during the war in Ukraine. He also oversaw the elimination of the last declared chemical weapons stockpile by the United States.—DARYL G. KIMBALL