Despite some significant accomplishments, the OPCW faces serious challenges and new threats.

June 2025

By Fernando Arias

The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) is an international organization made up of 193 states that are parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), a treaty that entered into force in April 1997.

By joining the CWC, the states-parties have committed themselves to the total elimination of all stockpiles of chemical weapons, abiding thus by the principles of zero tolerance and accepting the stringent OPCW verification system. As a result, after 28 years of OPCW efforts, more than 72,000 metric tonnes of chemical weapons declared by the states-parties have been irreversibly destroyed.

In 2023, the destruction of all declared chemical weapons was hailed as a great success, and a sign that the ethical and political taboo against the use of chemical weapons remains strong among states-parties.

The notion that chemical weapons are abhorrent and have no place in today’s world is firmly accepted and represents a consolidated understanding. In recent years, chemical weapons have been used in some countries, but their use has never been acknowledged by the perpetrators because of the strong taboo against their use.

Beyond the destruction of declared chemical weapons, the OPCW’s other main activities have included regular inspections of chemical industry sites, international cooperation and capacity-building programs, scientific research, and various types of investigations and assistance provided to the states-parties.

The purely technical nature of the organization’s mandate requires a strong corps of staff equipped with top-notch expertise in various scientific and technological fields. At the same time, because the membership is made up of states-parties, the OPCW also possesses a highly visible diplomatic component, directly affected by the political positions adopted by the states-parties in their capitals and conveyed to the organization through their respective ambassadors.

When the CWC was negotiated, some relevant stakeholders believed that following the elimination of all declared chemical weapons stockpiles, the OPCW could be shut down or downsized to a very small Secretariat, as the core goal of destruction would have been reached.

But given the recent significant advances in science and technology, as well as the unstable global world order, the organization is now more necessary than ever.

Today, emerging technologies provide new and powerful instruments that offer clear advantages, yet also pose serious risks. Drone technology, for example, has increased the ability to widely disseminate chemicals, while nanotechnology offers the possibility to reduce significantly the size of laboratories. With the advent of 3D printing technology, laboratory equipment now can be produced locally while avoiding international trade scrutiny.

Nanotechnology has reduced the size of laboratories and automation systems have boosted the capacity of chemical production. These developments also have allowed reductions in the number of staff with access to sensitive information, making it much more difficult to detect illicit production. Moreover, quantum computing with the necessary programs has become instrumental in the design of new chemicals. Together with artificial intelligence, the efficiency and power of these new technologies has increased exponentially.

In this context, the use of the internet in its various forms, including the dark web, has facilitated access—sometimes illegal—to equipment, chemical substances, different sorts of instruction manuals, and expert advice.

All of these new technical features present new risks and threats that create a far more complex and difficult environment to manage than the one in which the recently concluded destruction of classic chemical weapons took place.

All of these new technical features present new risks and threats that create a far more complex and difficult environment to manage than the one in which the recently concluded destruction of classic chemical weapons took place.

The most effective way to tackle these new threats is by ensuring there is always a combination of robust expertise in the OPCW Secretariat and that the OPCW agenda has the active support of the states-parties.

In this respect, the organization already has at its disposal a powerful instrument in the OPCW Centre for Chemistry and Technology, a facility inaugurated by King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands in May 2023.

The center was designed specifically to keep pace with the rapid international progress in science and technology. It is composed of a modern laboratory, multiuse training areas featuring state-of-the-art equipment, classrooms, meeting rooms, and a multipurpose atrium to cater to different types of activities.

The center’s potential is high: Many scientific research, training, and international-cooperation activities already are taking place there, and many more will be carried out in the coming years.

In addition, the Secretariat is paying particular attention to a number of other matters with the Syrian and Ukrainian dossiers being of high relevance.

Our task in Syria is very challenging. Its chemical weapons program became more open to complete elimination after Syrian President Bashar al-Assad was ousted in December 2024, and Ahmad al-Sharaa became the new caretaker president.

The Syrian chemical weapons dossier is a very old one. In 2005, Syria declared to the 1540 Committee of the United Nations that it had no chemical weapons. Eight years later, Syria became a member of the OPCW and declared its chemical weapons program to the organization, fully aware that the details would be verified by OPCW inspectors.

In its initial declaration, Syria listed 27 chemical weapons production facilities and 1,300 metric tonnes of chemical weapons stockpiles that were part of a program that had spanned four decades. All of the declared facilities and chemical agents were inspected by the OPCW and destroyed by the international community under the stringent OPCW verification system. Most of the 1,300 metric tonnes were destroyed outside of Syria.

Soon after Syria’s CWC accession, OPCW inspectors realized that the declaration was neither accurate nor complete. Moreover, there were indications that chemical weapons were still being used by the Assad regime.

To address these outstanding issues, the Secretariat established several special teams dedicated to the Syrian chemical weapons dossier. The Declaration Assessment Team has been in charge of clarifying the initial declaration of Syria, which was incomplete. After 28 rounds of consultations, the initial declaration submitted by the Syrian authorities was amended 20 times, and when the Assad regime fell in December there were still 19 outstanding issues, some of them of a very substantive nature.

The Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) has been responsible for determining whether toxic chemicals have been used as weapons in Syria. At the request of the former Syrian government, the FFM mandate did not include identifying who was responsible for any alleged attacks. The FFM has produced numerous reports confirming that toxic chemicals were used in Syria on repeated occasions.

On August 7, 2015, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2235 by consensus, creating the OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM) and expressing the determination to identify and hold accountable those responsible for the use of chemical weapons in Syria.

The JIM produced seven reports, attributing four cases of chemical weapons use to the Syrian Armed Forces of the Assad regime and three to the Islamic State. Because of disagreements at the Security Council, the JIM expired in November 2017 as its mandate was not renewed.

The CWC states-parties decided to hold a special session of the OPCW Conference of the States Parties in June 2018. The conference mandated that the OPCW Secretariat continue the task of the JIM, and set up the necessary arrangements to identify chemical weapons perpetrators in Syria.

As a result, the Secretariat decided to set up a new entity known as the Investigation and Identification Team (IIT) which, so far, has produced reports concerning six cases. The Assad regime’s armed forces were identified as chemical weapons perpetrators against the Syrian people in five of the cases and ISIS, in one case.

The role of the OPCW in identifying chemical weapons perpetrators finds its basis in a number of fundamental principles, namely that the use of chemical weapons is reprehensible and the perpetrators of such use in Syria should be held accountable. These principles are in line with the well established positions of the UN Security Council and General Assembly, other UN bodies, and those of a significant number of member states as expressed in their national statements to the UN and the OPCW. The principles also are laid down in the 2015 Ieper Declaration, which was issued for the centennial commemoration of the first large-scale use of chemical weapons during World War I.

Today, these common principles form an undisputed part of customary international law. In several instances, the Security Council has dealt with and discussed the content and findings of the IIT reports, thereby recognizing the role of the OPCW on this matter.

Over the past few years, the General Assembly has adopted resolutions, sponsored annually by Poland, concerning CWC implementation. The resolutions have stated that the individuals responsible for using chemical weapons should be held accountable and stressed the importance of the mandate conferred by the OPCW Conference in 2018 that originated the creation of the IIT.

After Assad’s fall, the OPCW Secretariat established contact with the new Syrian authorities, including with Sharaa and Foreign Minister Asaad al Shaibani. The high-level contacts and the deployments of the OPCW team of experts to Syria have been positive, and the new Syrian authorities, despite the difficult legacy they have inherited, are cooperating well with the OPCW.

The organization has a new and historic opportunity to obtain clarifications on the full extent and scope of the Syrian chemical weapons program. To do so, the Secretariat will need to have access to documents, locations, and people which, in turn, may shed further light on the program.

Establishing a full inventory of the components of the Assad chemical weapons program will be a difficult task, as the new authorities have very little knowledge about it. However, with the financial and political support of the states-parties and the knowledge of the OPCW experts, the organization will carry out this challenging task, visiting a large amount of chemical-weapons-related sites, to assess them, always counting on the goodwill and cooperation of the new Syrian authorities.

The situation in Ukraine has also required special attention. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the OPCW has been in contact with diplomats from both countries, which have repeatedly accused the other of using chemical weapons.

The situation in Ukraine has also required special attention. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the OPCW has been in contact with diplomats from both countries, which have repeatedly accused the other of using chemical weapons.

Upon Ukraine’s request, the OPCW Secretariat has provided assistance and protection programs to several groups of Ukrainian experts, and has already carried out technical assistance visits to Ukraine and produced two reports establishing that banned chemicals have been used on the front lines.

In China, meanwhile, operations continue for the excavation, recovery, and destruction of the chemical weapons abandoned by Japan at the end of World War II.

In the final days of the war, the Japanese Imperial Army, in its retreat, abandoned thousands of chemical weapons munitions in various provinces throughout China. The weapons were buried in pits and have remained there for many years, causing them to physically degrade.

Despite the clear degradation, most of the explosive charges and chemical agents contained in the munitions have been found to be still active. This has rendered the destruction of these abandoned munitions a dangerous, complex, and expensive endeavor.

Thanks to the good cooperation between China, Japan, and the OPCW; significant Japanese financial support; and Chinese logistical support more than 92,000 items of chemical weapons abandoned in China have already been recovered and destroyed, using sophisticated technology in a responsible manner that ensures protection for individuals and the environment. But the task is not yet complete.

As this undertaking has been and continues to be dangerous and complex, the Chinese and Japanese teams responsible for this process must be commended for their determination and courage.

On the global scale, despite the efforts of the states-parties over the last 30 years and the significant accomplishments made, the current situation is very challenging, with the OPCW facing traditional and new risks and threats.

Advances in science and technology provide the organization with new instruments that increase efficiencies, including in our laboratory and in the training of our experts, rendering the investigations and the findings related to alleged chemical weapons use more accurate.

However, advances in science and technology also provide new means for non-state actors to cause harm. In this context, the national implementing measures, namely domestic legislation, adopted by the states-parties is of paramount importance for the responsible implementation of the CWC.

Most states-parties already have enacted comprehensive legislation enabling their law enforcement, customs officials, judiciary, military, chemical industry, and international trade authorities to implement and enforce the obligations under the CWC on the territory of each state-party.

Unfortunately, today, one-third of the members have yet to adopt comprehensive legislation. The Secretariat conducts regular capacity-building activities and promotes international cooperation between states that have already enacted legislation and those that have yet to do so. This includes the sharing of templates of legislation already in force and the exchange of information between legal experts from different states.

Today, the OPCW is an active, responsible, and strong organization that provides concrete results.

Nevertheless, chemical weapons have been used in several countries over the last few years, new technologies present clear risks, and the international global geopolitical situation has produced a dramatically deteriorated security environment, with the international arms control structure facing a difficult moment.

In this context, the OPCW’s future success is not guaranteed. Nations must be reminded that the taboo against using chemical weapons can only be maintained when it is defended in a sustained manner.

The New Nuclear Age: At the Precipice of Armageddon

By Ankit Panda

Influence Without Arms: The New Logic of Nuclear Deterrence

By Matthew Fuhrmann

June 2025

The New Nuclear Age: At the Precipice of Armageddon

By Ankit Panda

Polity Press

2025

Ankit Panda details factors contributing to the “new nuclear age,” an unprecedented shift in the current nuclear security landscape that follows two other periods. The first, from the creation of the atomic bomb through the Cold War, was marked by Soviet-U.S. competition. The second featured growing proliferation concerns in South Asia and the Korean peninsula, as well as rapid reduction of the Russian and U.S. arsenals. The book focuses on the new nuclear age, which is characterized by the effects of recent technological advancements in weapons; new players, such as North Korea; and competition among China, Russia, and the United States. Panda details the historical context leading to this era, including debates on risks associated with deterrence. There is a special focus on advancements in missile defense, cyberattack capabilities, and artificial intelligence. The book also notes recent flashpoints in nuclear security threats and advocates for a return to restraint and arms control, with a focus on effective verification. Of note is Panda’s discussion of deterrence, which he argues shows evidence of preventing nuclear escalation. But unlike many proponents of deterrence, he assesses this approach as being entangled with coercion, and existing “as a function of the terror inherent in nuclear weapons.” The book is a timely overview of the emerging nuclear security landscape, informed by the need to combat increasingly complicated risks of nuclear escalation.—LIPI SHETTY

Influence Without Arms: The New Logic of Nuclear Deterrence

By Matthew Fuhrmann

Cambridge University Press

2024

Matthew Fuhrmann looks at nuclear deterrence through nuclear latency and analyzes how the capacity to build nuclear weapons can affect deterrence calculations and the move toward nuclear disarmament. He asserts that “a country’s influence would grow with shorter times to a bomb.” The author provides a complete theory of latent nuclear deterrence in two parts. First, he considers challenges that arise when using latency for influence, and then he provides potential mitigations for these challenges. Some of these challenges include delayed punishment; additional costs, such as sanctions; and regional instability. As potential solutions, he lists nuclear restraint, variable enrichment reprocessing, and using nuclear latency to mitigate other conflicts in a given region. Through 20 case studies and detailed historical records, Fuhrmann argues that nuclear latency can be used to deter adversaries. In his final chapter, the author synthesizes his findings and their potential contributions to nuclear disarmament and proliferation. His final lesson is that “weaponless deterrence may open the door to nuclear disarmament.” Fuhrmann calls for increased investigation into latent nuclear deterrence theories as they apply to fissile material production capacity, foreign perceptions of the intentions of states that are pursuing nuclear-related activities, verification, the survivability of latent nuclear capability, and parity in breakout times—LIBBY FLATOFF

June 2025

A History of Nuclear Haves and Have-Nots

The Struggle for Abolition: Power and Legitimacy

in Multilateral Nuclear Disarmament Diplomacy

By Kjølv Egeland

Routledge

2025

Reviewed by Naomi Egel

Kjølv Egeland’s The Struggle for Abolition: Power and Legitimacy in Multilateral Nuclear Disarmament Diplomacy traces the history of disarmament efforts from the 1968 adoption of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) to the 2021 entry into force of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). In those five decades, Egeland covers the high points of disarmament efforts such as the TPNW and the first UN Special Session on Disarmament, as well as the disappointments and unmet aspirations, from the 1975 NPT Review Conference to the third UN Special Session on Disarmament in 1988.

The word “struggle” in the book’s title aptly characterizes the history of disarmament efforts. The book shows how the dissatisfaction of non-nuclear, mostly neutral, and nonaligned states lacking progress toward disarmament and lacking recognition of their role as sovereign equals led to crises of legitimacy in multilateral disarmament diplomacy. Those crises were at times resolved through institutional reforms and greater commitments by nuclear-weapon states to future nuclear disarmament. In other instances, failures to achieve such reforms and commitments deepened divides between nuclear weapon states and non-nuclear-weapon states.

Egeland contends that the effectiveness of nuclear-weapon states’ efforts to ward off these challenges and reforms depended on when they are taken. They were more likely to succeed when dissatisfied non-nuclear-weapon states still viewed the “nuclear regime complex,” generally understood to be the set of international rules and agreements governing nuclear weapons, as having high legitimacy, and less likely to succeed when such non-nuclear-weapon states viewed the regime as having low legitimacy.

After introducing the concepts of nuclear order and recognition in Chapter 1, subsequent chapters each consider a time period in the development of the nuclear regime complex. Chapter 2 covers the period between 1969 and 1978, Chapter 3 examines 1979 to 2000, and Chapter 4 addresses 2001 to 2021. By taking a chronological approach to understanding disarmament diplomacy, Egeland draws the reader’s attention to underappreciated moments, initiatives, and events that shaped subsequent disarmament efforts.

For example, although the 1996 Model Nuclear Weapons Convention failed to gain traction at the time, it provided a rallying point and a basis upon which nongovernmental organizations and states later pursued the TPNW. The chronological approach to disarmament diplomacy also underscores how long many disarmament efforts have been in the works. For example, Egeland demonstrates how disarmament diplomats and advocates pursued the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty in the early 1960s, in the context of the development of the Limited Test Ban Treaty, and in the 1990s, and in the intervening years as well.

A central theme of the book is the efforts by non-nuclear-weapon states to achieve recognition as sovereign equals by nuclear-weapon states and to have their priorities and objectives given equal weight to those of nuclear-weapon states. This echoes other scholarship that has emphasized the importance of status-seeking and the desire of smaller states to overcome international hierarchies as a motivator for state action in world politics.1 The Struggle for Abolition underscores the need to take seriously the nonmaterial factors that shape states’ negotiating behaviors in disarmament diplomacy.

Yet this coupling of recognition and disarmament can have the consequence of underappreciating progress toward disarmament that lacked a central role for non-nuclear-weapon states. If disarmament and recognition go hand in hand, steps toward disarmament negotiated by nuclear-weapon states are unlikely to satisfy the recognition demands of certain non-nuclear-weapon states. In describing the reaction of non-nuclear-weapon states to bilateral U.S.-Russian and U.S.-Soviet arms control agreements, the book shows that states at the forefront of disarmament advocacy were disappointed and underwhelmed by the products of bilateral superpower arms control negotiations that lacked participation from non-nuclear-weapon states and that were concluded during periods of disagreement in multilateral disarmament diplomacy.

Conversely, the pairing of disarmament and recognition can lead such states to emphasize the importance of measures that had few material implications but were significant in terms of recognition. For example, in discussing the development of the NPT, Egeland concludes, “If judged as an attempt at tackling the neutral and non-aligned states’ material security dilemma vis-à-vis the nuclear-weapon states and their allies, the NPT’s disarmament language looks next to worthless.” However, “by casting the NPT as a step towards disarmament, Article VI allowed the non-nuclear-weapon states to describe themselves not simply as ‘inferior’ or ‘unequal’, but as ‘equal in waiting.’”

Likewise, in contrasting these states’ positive reaction to the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) II, which never entered force as a treaty, and their scorn of SALT I, which did enter into force as a formal treaty, he notes, “What had changed over the course of the second half of the 1970s, of course, was not the contents of SALT but the social environment in which nuclear diplomacy was enacted.” These different reactions to various steps toward disarmament underscore the importance of non-material factors and of recognition, in anticipating whether an action or agreement is likely to satisfy states seeking disarmament.

Although the book does not limit its focus to any specific states, neutral and nonaligned states are often at the center of the struggle for both disarmament and recognition. Sweden and Mexico appear repeatedly as strong disarmament advocates. Yet Sweden’s approach to disarmament and nuclear weapons has changed in recent years. Sweden did not vote in favor of the TPNW in 2017, did not join the TPNW, and has joined NATO since the TPNW entered into force. Although Sweden was a strong Cold War disarmament advocate, it has played a less prominent role in the post-Cold War period, especially after 2010, even before it joined NATO.

Mexico, meanwhile, consistently has been at the forefront of disarmament diplomacy. This raises interesting questions of how stalwart certain states or other actors are in disarmament advocacy: Why do certain actors take leadership roles in disarmament advocacy and why, at some point, do they step back from those roles? If disarmament diplomacy and sovereign recognition go together, why would Sweden reverse its approach, unlike other countries? It does not appear that Sweden’s desire for recognition was fully met or that sufficient progress on disarmament was achieved. More broadly, when is disarmament diplomacy a priority for states and when does it stop being so? Understanding the prioritization of disarmament diplomacy not as a constant attribute of certain states, but as a dynamic shaped by external and internal factors, can help identify when recognition concerns are likely to be especially salient, and for which states.

Lurking through the book is the question of the extent to which disarmament diplomacy and the nuclear regime complex are a distinct negotiating space versus an area of negotiation shaped by external events. At times, the disagreements and the divide between non-nuclear-weapon states seeking disarmament and nuclear-armed states reflects the distinction between haves and have-nots in terms of nuclear weapons. At other times, Egeland and the actors he examines in his book explicitly link crises of legitimacy in the nuclear regime complex to broader divides in world politics, especially those between former colonizers and the formerly colonized, or great powers and the rest. The extent to which disarmament diplomacy is insulated from external events matters because it points to alternatively narrower or broader paths through which legitimacy can be undermined and through which recognition can be achieved.

What does the struggle for nuclear abolition look like today? As nuclear-weapon states appear uninterested in arms control limits or reductions, nuclear and non-nuclear multilateral institutions are under strain, and the NPT continues to be mired in perpetual crisis, prospects for nuclear disarmament appear dim. As a result, the nuclear regime complex appears to have very low levels of legitimacy for many non-nuclear-weapon states. At the same time, the United States and Russia appear less concerned with multilateralism and disarmament diplomacy than perhaps ever, and are reluctant to recognize non-nuclear-weapon states as equals. Domestic actors in countries such as Poland and South Korea are increasingly discussing the possibility of developing their own nuclear weapons.

Yet as Egeland shows, earlier disarmament efforts can lay the groundwork for later achievements, even if they do not succeed at first. Moreover, the nuclear regime complex has contributed to important norms, including taboos against nuclear testing and nuclear use, which have endured. Nonetheless, in a context in which the dominant nuclear-weapon states appear less influenced by international norms and less responsive to pressure from non-nuclear-weapon states, the nuclear regime complex faces serious challenges to sustain past successes, let alone make further progress.

Extensively researched, with rich archival evidence and interviews with participants in disarmament negotiations, The Struggle for Abolition is an important contribution to understanding why the nuclear regime complex has endured thus far, how it has evolved, and how cycles of legitimacy crises have shaped it. By centering the role of non-nuclear-weapon states, this book provides a valuable addition to work that has been more focused on the role of the United States in developing and sustaining the multilateral nonproliferation regime.

ENDNOTES

1. For example, Benjamin de Carvalho and Iver Neumann, eds., Small State Status Seeking: Norway’s Quest for International Standing. (London: Taylor & Francis, 2014); Vincent Pouliot, International Pecking Orders: The Politics and Practice of Multilateral Diplomacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016); Naomi Egel and Steven Ward, “Hierarchy, revisionism, and subordinate actors: The TPNW and the subversion of the nuclear order,” European Journal of International Relations Vol. 28, No. 4 (2022): 751-776; and Rohan Mukherjee, Ascending Order: Rising Powers and the Politics of Status in International Institutions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Naomi Egel is an assistant professor in the Department of International Affairs and a faculty fellow at the Center for International Trade and Security at the University of Georgia.

At the age of 24, Garwin, a physicist, designed the 1952 Ivy-Mike nuclear explosion test that ushered in the first hydrogen bombs.

June 2025

By Raymond Jeanloz

Richard Garwin, who died last month at the age of 97, is best known for designing the 1952 Ivy Mike nuclear explosion test. It vaporized the island of Elugelab in the Eniwetok Atoll and ushered in the U.S. development and deployment of the first hydrogen bombs. Garwin was 24 at the time.

Less widely known is his tireless work in arms control and disarmament. Over more than half a century, he addressed the threats of nuclear weapons and nonproliferation, global war, conflict in space, terrorism, and bioweapons. Garwin participated in security meetings run by the Pugwash Conferences, the International School on Disarmament and Research on Conflicts and Amaldi Global Security starting in the 1970s; served as vice chair of the Federation of American Scientists, which holds an archive of his papers; and chaired the U.S. State Department’s Arms Control and Nonproliferation Advisory Board from 1993 to 2001.

By far his longest association, however, was with the U.S. National Academy of Sciences Committee on International Security and Arms Control (CISAC). He was a member from 1980 to 2023 and an observer thereafter. The committee serves the United States by providing a quiet venue for discussions with foreign technical, military, and policy experts on nuclear, biological, cyber, and space security; arms control; and nonproliferation. This involved regular meetings with Russia, China and India that have been underway for decades.

Garwin contributed significantly to innumerable meetings with these foreign counterparts. He was committed to documenting ideas in writing, coauthoring such CISAC reports as: Nuclear Arms Control: Background and Issues (1985); The Future of the U.S.-Soviet Nuclear Relationship (1991); Monitoring Nuclear Weapons and Nuclear Explosive Materials (2005). He co-wrote Making the Nation Safer: The Role of Science and Technology in Countering Terrorism (2002) after the September 11 attacks.

The National Academy suited him as a venue, as he could emphasize technical matters in discussions bearing on public policy. Garwin was relentless in bringing the logic of engineering and science to each conversation, including on topics that are frightening and therefore emotional. The objective was to provide evidence-based advice, applying the scientific method as vetted by expert peer review.

A focus on technical matters helps initiate arms control discussions. After all, some of the world’s most daunting challenges, such as control of nuclear arsenals, are among the consequences of scientific discovery and the resulting technologies must be understood to be contained. Science and engineering can also provide solutions for arms control, from developing monitoring technologies for verifying treaties to establishing communication channels to avoid crisis.

Garwin brought the international aspects of science to bear, with researchers comparing, competing and, when appropriate, collaborating with each other worldwide. His own scientific collaborators ranged from George Charpak (Megawars and Megatons, 2001) in France to Antonino Zichichi and his Ettore Majorana Centre in Sicily.

More generally, Garwin could appreciate the capabilities of a foreign colleague without needing to agree with the actions or motivations of that individual’s government. This spirit of international technical collaboration made him unusually effective in discussions with counterparts from Russia, China and other nations with which the United States has sustained dialogues. Garwin pointed out unjustified assumptions or flaws in colleagues’ technical analyses as readily as he acknowledged the validity of a point with which he concurred.

The interactions were no less courteous and professional than one would expect for the best of scientific meetings, even when discussions broached topics about unprecedented death and destruction.

Garwin had a special appreciation for the people of China, where he and his wife Lois traveled for more than 40 years. After his first visits in the 1970s, he engaged with scientists and military officers of China’s nuclear-weapons community through CISAC, playing a key role in the production of the English-Chinese, Chinese-English Nuclear Security Glossary (2007). This unique volume is intended to help governments and the arms control community by reducing misunderstandings of concepts and definitions.

His efforts have been appreciated in China as in the United States, with a leading Chinese counterpart writing in 2014, that “Dr. Garwin has contributed enormously to enhance communications, cooperation, and mutual trust, as well as understanding both between the peoples of the two nations and especially the scientists.”

For Garwin, the essential matter is that facts of nature exist independent of humans. Some facts are eventually discovered by humans, often without anticipation, let alone preparation. Yet it is up to humans to decide how to develop, deploy, and ultimately control the resulting technologies to the betterment of humanity.

The agency is accepting public comments until July 14 on the impact of plans to produce plutonium pits at the Savannah River Site.

June 2025

By Lipi Shetty

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) gave formal notice May 9 that it would prepare a nationwide, programmatic environmental impact statement on its proposed plutonium pit production plans.

According to the notice, the NNSA has identified 13 potential focal issues for inclusion in the statement, including the impacts of the generation, transportation, and disposal of radioactive waste. Two virtual public meetings were held May 27 and May 28, to gather initial feedback on the impact statement. NNSA is also accepting written public comments until July 14.

The environmental impact statement is the result of a September 2024 ruling by a U.S. district judge that the NNSA violated the National Environmental Policy Act by failing to properly consider environmental impacts and analyze alternatives to its plutonium pit production plans announced in 2018. (See ACT, November 2024.) As a part of a rapid expansion of U.S. nuclear weapons production, the 2018 plan aims to produce 30 pits per year at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico and 50 pits at the Savannah River Site in South Carolina.

The lawsuit, which resulted in a January 2025 settlement, was filed by the South Carolina Environmental Law Project representing the Gullah/Geechee Sea Island Coalition and Nuclear Watch New Mexico, Savannah River Site Watch, and Tri-Valley Communities Against a Radioactive Environment. (See ACT, March 2025.)

According to a Jan. 17 press release by the plaintiffs, the settlement required the NNSA to halt all production preparations at the Savannah River Site until completion of the environmental impact statement within two and half years.

In a joint statement May 9, the plaintiffs highlighted the centrality of the plutonium pit production effort to the broader U.S. nuclear modernization plan and urged the public to engage in the commenting process.

Comments on the scope of the programmatic environmental impact statement can be emailed to [email protected] or mailed to National Nuclear Security Administration, Office of Pit Production Modernization, U.S. Department of Energy, 1000 Independence Ave. SW, Washington, DC 20585. The NNSA expects it will issue the draft impact statement in one year and will issue the final report and record decision within two years.

The final preparatory committee meeting ahead of the 2026 nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference ended with little optimism that there will be a consensus outcome document next year.

June 2025

By Sizuka Kuramitsu, Lipi Shetty, and Daryl G. Kimball

The third and final preparatory committee meeting ahead of the 2026 nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference ended May 9 with little room for optimism for agreement on a consensus outcome document next year.

The review process is designed to bring together the 191 NPT states-parties to formally review compliance with and implementation of the treaty’s three pillars of disarmament, nonproliferation, and peaceful uses of nuclear energy.

According to diplomatic sources who spoke with Arms Control Today, the two-week-long preparatory meeting came close to consensus on a draft package of proposals for strengthening the review process, but disputes among some NPT nuclear-armed states, including China, emerged on the final day.

The impasse over strengthening the review process scuttled any further efforts to reach an agreement on a separate draft package of substantive recommendations for the Review Conference, which the president of the meeting, Harold Agyeman of Ghana, circulated for consideration.

In his opening statement, Agyeman emphasized that the NPT is under stress. “Today, we stand at a crossroads, and the credibility of the treaty, which for 50 [years] has served as the cornerstone of global non-proliferation and nuclear disarmament efforts, is challenged, within a context where predictability is required more than ever,” he said April 28.

“As we therefore complete the final lap towards the 2026 Review Conference, my appeal to states-parties is simple. Time is running out on us and we must be ready to see the bigger picture, to put aside our national differences and work collectively towards the goal of a world free of nuclear weapons that preserves the human civilisation.”

Although the vast majority of states did seek to find common ground, differences among the NPT’s nuclear-armed states continued to dog the discussions and stymie progress.

During the two week preparatory committee meeting, states-parties voiced various concerns about existing and emerging threats to the treaty, including the impact of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on the global nuclear order; China’s nuclear weapons build-up; the forward deployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in Europe; Russian nuclear weapons in Belarus; threats to the global nuclear test moratorium; and the failure of the five NPT nuclear-armed states to engage in negotiations on disarmament, which is a central obligation under

Article VI of the treaty.

As states agreed at the 2000 Review Conference, the third preparatory committee should take stock of the two previous preparatory committee meetings and “make every effort to produce a consensus report containing recommendations” for the following year’s review conference. But as was the case in the past, the states-parties could not produce substantive recommendations for the next year’s conference by consensus.

As at previous preparatory committee meetings, a group of 48 states issued a joint statement to condemn Russia’s war against Ukraine including the occupation of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant and nuclear sharing with Belarus. “We condemn in the strongest possible terms Russia’s irresponsible and threatening nuclear rhetoric as well as its posture of strategic intimidation, including its announced deployment of nuclear weapons in Belarus,” read the joint statement.

In keeping with recent U.S. abstentions in other fora on the subject since the inauguration of President Donald Trump, the United States did not join the statement condemning Russia.

The United States, represented by a less senior delegation than in years past, reiterated Trump’s statements expressing a readiness to talk with China and Russia on “denuclearization.” The statements also sought to contrast the U.S. record on its relative transparency regarding its nuclear arsenals and nuclear posture with that of China.

Referring to Trump, Paul Watzlavick, the recently appointed head of the U.S. delegation, said April 29: “He has made clear his desire to address the threat posed by Russia and China’s nuclear arsenals.”

“In sharp contrast to China’s opaque nuclear weapons build-up, the United States has been remarkably transparent, releasing the number of weapons in our stockpile twice in the last four years. However, for too long U.S. leadership and transparency have not been met with reciprocity by China and Russia,” Watzlavick said.

The closing session on May 9 opened with several joint statements, including one delivered by Ireland on behalf of 49 states-parties on the importance of strengthening transparency and accountability measures.

Referring to the fast approaching expiration of the last remaining treaty limiting the Russian and U.S. nuclear arsenals, the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), Austria also took to the floor to deliver a joint statement on behalf of 24 states calling on the United States and Russia to re-engage on nuclear disarmament and to refrain from increasing the size of their deployed strategic arsenals after New START expires on Feb. 6, 2026.

Underscoring the importance of disarmament under current high tensions, it is “urgent to preserve and achieve further reduction and limitations of deployed strategic nuclear arsenals,” the joint statement said.

It also called “for the urgent commencement of negotiations for a successor agreement and … for a return to full and mutual compliance with the limits set by the treaty until such time as a successor pact is concluded in order to secure the achievements of the New START Treaty before its expiry and to achieve further progress on the limits on and reduction of deployed strategic nuclear arsenals.”

The 2026 NPT Review Conference is set for April 27 to May 22 in New York and will be chaired by Vietnam. The last time an NPT review conference adopted a substantive outcome document by consensus was in 2010.

Some U.S. officials say the plan likely will reduce the capacity of the government to deal with the broad range of arms control and disarmament challenges.

June 2025

By Daryl G. Kimball

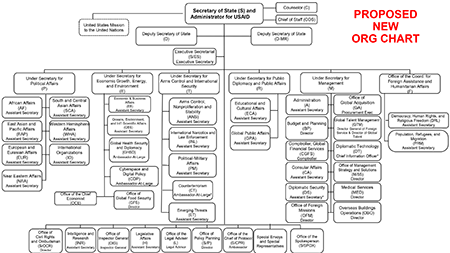

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced plans for a sweeping overhaul and downsizing of the State Department, including reducing U.S.-based staff by 15 percent and closing or consolidating more than 100 bureaus overseas.

“We cannot win the battle for the 21st century with bloated bureaucracy that stifles innovation and misallocates scarce resources,” Rubio said April 22 in a department-wide email obtained by the Associated Press. He said the reorganization aimed to “meet the immense challenges of the 21st century and put America First.”

Overall, Rubio’s plan calls for reducing the number of bureaus and offices from 734 to 602 through consolidation or elimination, according to a department fact sheet.

In addition to structural “efficiencies,” the proposed organizational chart would make several major functional changes, including eliminating the most senior department position dedicated to human rights and civilian security, abolishing the equity and global accountability offices, and further dismantling the U.S. Agency for International Development.

The plan also calls for another reorganization of the bureaus overseen by the undersecretary of state for arms control and international security that deal with nonproliferation, arms control and disarmament, which have been reshuffled four times since the late-1990s.

Rubio’s plan would fold the International Security and Nonproliferation Bureau (ISN) and the Arms Control, Deterrence, and Stability Bureau (ADS), formerly the Arms Control, Verification, and Compliance Bureau (AVC), into a single bureau with one assistant secretary instead of two.

The newly combined Arms Control, Nonproliferation, and Stability Bureau would become one of five bureaus (instead of the current three) under the Office of the Undersecretary for Arms Control and International Security. The other four new bureaus would be: International Narcotics and Law Enforcement; Political-Military Affairs; Counterterrorism; and Emerging Threats.

According to current and former U.S. officials, the consolidation of the ADS and ISN bureaus likely will reduce the capacity of the department and the government as a whole to deal with the broad range of arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament challenges.

By expanding the scope of the issues for which the undersecretary of state for international security and arms control would be responsible and eliminating one of the two assistant secretaries, there will be less time and fewer senior officials available to deal with these critical issues.

In addition, U.S. officials note that potential staffing cuts and retirements could diminish the specialized expertise that senior decision-makers at the State Department and other executive branch agencies depend on to formulate and implement policy on nuclear, chemical, biological, and conventional arms control and nonproliferation matters, civilian nuclear cooperation, space security, security assistance programs, and conventional arms trade policy.

The Trump administration has nominated Thomas DiNanno to be the new undersecretary of state for international security and arms control. The Senate has not yet voted on his confirmation for the post.

The Rubio proposal would further downsize the number of personnel responsible for a wide range of nonproliferation, arms control, and disarmament matters and is part of a longer-term trend underway since the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, first established in 1961 as an independent entity during the Kennedy administration, was folded into the State Department in 1999 during the Clinton administration. (See ACT, April 1997.) This ACDA merger led to the creation of the position of undersecretary for arms control and international security.

In 2005, the Bush administration merged the arms control and nonproliferation bureaus into the current ISN bureau. In addition, the verification and compliance bureau was expanded to include implementation. (See ACT, October 2005.)

In 2010, the Obama administration renamed the Bureau of Verification, Compliance, and Implementation (VCI) to become the Bureau of Arms Control, Verification and Compliance (AVC) and a number of offices in the ISN bureau were moved into the AVC. The ISN and Political-Military Affairs bureaus remained unchanged. At the time, Sen. Richard Lugar (R-Ind.), ranking member on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, opposed the idea of combining the arms control and verification functions within a single bureau. (See ACT, November 2010.)

The latest proposed State Department changes have not yet been completed and Congress may decide to weigh in, but the department is moving forward with the plan.

It is not yet clear how the proposed reorganization will align with the results of the 180-day review of U.S. treaties and funding of international organizations that was mandated by a presidential executive order issued February 4.

The order directs that the secretary of state “conduct a review of all international intergovernmental organizations of which the United States is a member and provides any type of funding or other support, and all conventions and treaties to which the United States is a party, to determine which organizations, conventions, and treaties are contrary to the interests of the United States and whether such organizations, conventions, or treaties can be reformed.”

The review is to include “recommendations as to whether the United States should withdraw from any such organizations, conventions, or treaties.”

On May 2, the Trump administration also released an outline of its fiscal year 2026 budget request to Congress that calls for a $1.7 billion reduction in assessed and voluntary contributions to international organizations.

It states that “the budget pauses most assessed and voluntary contributions to UN and other international organizations, including the UN regular budget” in order “to preserve maximum negotiating leverage.”

Rubio, who was named acting national security advisor following the dismissal of Michael Waltz in April, has also moved to downsize significantly the National Security Council.

The Trump administration’s plan to reach that total has left some congressional defense leaders dissatisfied.

June 2025

By Xiaodon Liang

U.S. President Donald Trump has proposed the first ever $1 trillion defense budget, but his administration’s plan to reach that total has left some congressional defense leaders dissatisfied.

On May 2, the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) released the Trump administration’s budget request for fiscal year 2026. The budget plan, presented in an abbreviated preliminary form, includes a base defense request of $892.6 billion, plus a $119.3 billion allocation of additional resources from the Republican-controlled Congress’ budget reconciliation bill

That bill, which includes $150 billion in additional defense spending over the next four fiscal years, remains the subject of intense negotiations between factions of the Republican Party. If those negotiations fail and the additional funds are not made available, the overall defense budget request will remain flat compared with the final amount appropriated by Congress for fiscal 2025. (See ACT, April 2025.)

The “reconciliation bill was always meant to change fundamentally the direction of the Pentagon … not to paper over OMB’s intent to shred to the bone our military capabilities and our support to service members,” said Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.), chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, in a May 2 press statement.

The House Armed Services Committee approved its portion of the reconciliation bill April 29, distributing the $150 billion in additional defense spending across several priorities. These include nuclear forces, which would receive an additional $12.9 billion, and integrated air and missile defense, which would receive $24.7 billion. The administration is yet to provide detailed information on how the base defense budget would be allocated.

“Gifting the Pentagon an additional $150 billion with little to no guard rails, on top of the nearly $900 billion defense budget already passed and without any budget plan from the President for Fiscal Year 2026 or even execution instructions for FY25, defies basic common sense,” said Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.), ranking member of the committee, in an Apr. 27 statement.

Within the nuclear forces budget, the House committee would allocate an additional $1.5 billion for “risk reduction” activities of the Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) program. Technological maturation and risk reduction (TMRR) is a phase of the R&D process that precedes engineering and manufacturing development (EMD). Following last year’s Nunn-McCurdy review of the Sentinel, the Defense Department rescinded the ICBM program’s authorization to proceed from TMRR to EMD.

The House committee bill also would provide $500 million for improvements to the Minuteman III ICBM. The Air Force is considering plans to keep that missile in service through 2050, Bloomberg News reported March 27.

The nuclear-capable sea-launched cruise missile program, which was opposed by the Biden administration but nevertheless funded by Congress in fiscal 2025, would receive $2 billion. A further $400 million would be made available for the National Nuclear Security Administration’s work on the new missile’s warhead.

The bill also would earmark $62 million to reopen missile tubes aboard the Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines. Those tubes were sealed as part of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, which is set to expire after Feb. 5, 2026.

The House bill would provide $4.5 billion for accelerated production of the B-21 bomber. (See ACT, May 2025.)

Although the Trump administration has released few details about the Golden Dome missile defense architecture, the House bill would provide $5.6 billion to develop “space-based and boost phase intercept capabilities.” An amendment introduced by Rep. Eugene Vindman (D-Va.) to strip $2.6 billion in funding from the program failed on a party-line vote.

The House proposal to increase spending on nuclear programs comes days after the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released the newest edition of a biannual estimate of the cost of U.S. nuclear forces. The CBO now calculates that the United States will spend $946 billion over the next decade—2025 to 2034—on nuclear modernization, operations, and sustainment.

The CBO approach to calculating total nuclear spending tabulates programmatic costs as published in presidential budget requests; extrapolates those costs over 10 years using public information about each program; and then adds an estimate of expected cost growth based on historical programs. The report noted $817 billion in programmatic spending over the next decade, with a further $129 billion in likely cost growth.

Thirty-eight percent of the nuclear spending will be taken up by the modernization of delivery systems within the Defense Department, while another 9 percent is attributable to expansion of the Department of Energy’s weapons complex.

Ten percent will go toward modernization of nuclear command and control systems, while the remainder—roughly

44 percent—pays for ongoing operations and sustainment.

CBO estimates that nuclear forces will account for 11.8 percent of the Defense Department’s total acquisition costs over the 10-year period, peaking at 13.2 percent in 2031.

Notably, however, the CBO estimates do not include cost overruns for the Sentinel ICBM that were publicized after the fiscal 2025 presidential budget request was released. The CBO estimate therefore excludes the cost implications of the Nunn-McCurdy review conclusion that the ICBM is expected to cost 81 percent more than a baseline of $77.8 billion in 2020 dollars. Instead, it assumes that the program is 37 percent over baseline, as the Defense Department informed Congress in late 2023. (See ACT, September 2024.)

It was the worst outbreak of direct military violence between the South Asian neighbors since the 1999 Kargil War.

June 2025

By Daryl Kimball and Xiaodon Liang

In a renewed flareup between nuclear-armed rivals, India and Pakistan fired conventionally armed missiles, drones, and artillery shells at each other in early May, in the worst outbreak of direct military violence between the South Asian neighbors since the 1999 Kargil War.

At the urging of top leaders from several states, including China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Pakistan’s army chief, Gen. Syed Asim Munir, agreed to a ceasefire, halting the fighting before it might have led to a full-scale ground war and a nuclear exchange.

Between May 6 and May 10, the two sides struck military bases inside the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir, and beyond. On May 10, U.S. President Donald Trump announced that U.S. mediation had secured a ceasefire, which both sides confirmed later that afternoon.

The exchange of long-range attacks was preceded by a crisis that began April 22, when an armed group killed 26 civilians in Pahalgam, a town in Indian-controlled Kashmir. India claims the Pahalgam attack was carried out by “Pakistani and Pakistan-trained terrorists belonging to the Lashkar-e-Taiba” militant group, according to a May 7 statement by Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri. Pakistan denied involvement in the attack.

Following India’s April 24 announcement that it would suspend the Indus Waters Treaty, which governs rights to shared riparian waters, Pakistan declared that it would react with “full force across the complete spectrum of national power,” a not-so-veiled reference to the possible use of nuclear weapons.

Under increasing domestic pressure to retaliate, the Modi government launched a major air strike May 6 against alleged “terrorist infrastructure” at nine sites in Pakistani-controlled Kashmir and other provinces of Pakistan. Pakistan claimed in a May 8 press release that the attack led to 31 deaths and 57 injuries.

Pakistan says it shot down five Indian air force combat jets May 6, including several French Dassault Rafale fighters. Although India has not acknowledged these losses, U.S. officials told Reuters May 8 that Chinese-origin Pakistani aircraft had downed at least two Indian combat jets, one of which was a Rafale. A French intelligence official also confirmed the loss of at least one Rafale jet to CNN May 7.

Subsequent rounds of missile and drone attacks by each side against civilian and military targets were accompanied by reported shelling of military positions along the Line of Control, the de facto border in Kashmir.

In the early morning of May 10, Indian missiles and drones targeted several Pakistani air bases outside Kashmir, including Nur Khan air base in Rawalpindi, according to a Pakistani military spokesman. On the same day, Pakistan launched attacks against Indian air bases and BrahMos hypersonic cruise missile storage sites in Kashmir, Punjab, and Gujarat.

In a press release, the Indian government claimed that the Pakistani director-general of military operations reached out to offer a ceasefire in the afternoon. Pakistan disputes that it initiated contact.

“The Indians requested a ceasefire after the 8th and 9th of May after they started their operation. We told them we will communicate back after our retribution,” Pakistani Lt. Gen. Ahmed Sharif Chaudhry said at a May 11 press conference.

The two countries also dispute the extent to which the United States was involved in brokering a ceasefire agreement. Although Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif thanked U.S. officials for their diplomatic intervention in a May 10 social media post, Indian officials have maintained that ceasefire negotiations were bilateral.

Reporting by U.S. news outlets suggests that U.S. officials were actively engaged in defusing the crisis. U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who is also acting national security advisor, held multiple phone calls with Indian and Pakistani officials beginning May 6, according to Reuters. Rubio and Vice President J.D. Vance proposed a plan for U.S. intermediation to Trump on May 9, after which Vance spoke with Modi to express U.S. concerns of a “dramatic escalation,” an unnamed source told the newswire.

But top U.S. officials became particularly concerned after the alleged Indian strike on the Nur Khan air base, which is near Pakistani military headquarters and also the Strategic Plans Division, which oversees nuclear forces, The New York Times reported.

Pakistani Defense Minister Khawaja Muhammad Asif said his country would only use nuclear weapons if “there is a direct threat to our existence,” in an April 28 interview with Reuters. With approximately 170 nuclear warheads each, India and Pakistan have enough nuclear firepower to obliterate the other; Pakistani doctrine retains the option to use nuclear weapons first against non-nuclear military threats.

In previous crises sparked by terrorist attacks in India, New Delhi has shown more relative restraint in its response. In January 2016, after militants attacked the Pathankot air base in northern Punjab, Pakistan made initial steps to investigate and arrest suspects tied to the multiday assault.

When a Kashmiri militant attacked an Indian paramilitary convoy in February 2019 in the Pulwama district of Indian-controlled Kashmir, India launched air strikes against a suspected terrorist base in Pakistan, outside of the Pakistani-controlled portion of the disputed territory. But during that crisis, no military bases were targeted.

In the wake of the latest conflict, Indian and Pakistani officials sought to depict to their publics and the world that their respective military operations were responsible and successful. But the underlying factors that led to this war and previous nuclear-tinged crises since the tit-for-tat Indian and Pakistani nuclear tests of 1998 still appear to exist: the possibility of cross-border terrorism by anti-Indian militia groups, the absence of regular dialogue between the two governments, and the presence of nuclear weapons.

Since the ceasefire was concluded, India and Pakistan have traded threats and made accusations of nuclear-weapons mismanagement. On May 12, Modi said India would strike at militant hideouts across the border again if there were new attacks on India and would not be deterred by what he referred to as Islamabad’s “nuclear blackmail.”

On May 15, Indian Defense Minister Rajnath Singh questioned the safety of nuclear weapons in Pakistan, calling it an “irresponsible and rogue nation.”“I believe that Pakistan’s nuclear weapons should be taken under the supervision of [the International Atomic Energy Agency],” Singh said.

In response, Pakistan’s Foreign Affairs Ministry said in a statement that Singh had revealed his “profound insecurity and frustration regarding Pakistan’s effective defence and deterrence.”

The accusation came shortly before U.S. President Donald Trump unveiled further details of his ‘Golden Dome’ missile defense system.

June 2025

By Xiaodon Liang

In an extended criticism of the Trump administration’s “deeply destabilizing” plans for a homeland missile defense shield, Beijing and Moscow allege that Washington is deliberately acquiring a “first strike” capability that creates “hardly surmountable obstacles to the constructive consideration of nuclear arms control and nuclear disarmament initiatives.”

The accusation, contained in a May 8 joint statement on global strategic stability, came shortly before U.S. President Donald Trump unveiled further details of his “Golden Dome” missile defense system (See ACT, March 2025). The new system “will be capable of intercepting missiles even if they are launched from other sides of the world and even if they are launched from space,” Trump announced May 20 at a White House press conference.

Gen. Michael Guetlein, the vice chief of operations at the U.S. Space Force, will lead the Golden Dome program, Trump said.

His comments focused primarily on a system of space-based interceptors for boost-phase intercept of adversary missiles, which Trump says will cost $175 billion and three years to complete. But in a separate statement issued by the Defense Department following the press conference, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth said the Golden Dome will be a “system of systems” that “is designed to leverage some past investments.”

“All of the systems comprising the Golden Dome architecture will need to be seamlessly integrated,” Hegseth said. It “will be fielded in phases, prioritizing defense where the threat is greatest.”

Andrea Yaffe, the acting principal deputy assistant secretary of defense for space policy, told senators May 13 that the department has developed several missile defense architecture options, which were then presented by Hegseth to Trump. Yaffe spoke in response to questioning by Sen. Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.) in a hearing before the Strategic Forces subcommittee of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

Although that key subcommittee is split over the merits of the president’s missile defense plan, senators acknowledged that a full assessment of the architecture would require more detail when the full defense budget arrives.

The “economics don’t work,” said Sen. Angus King (I-Maine), the subcommittee’s ranking member, pressing Yaffe and other officials to explain how a missile defense shield could defend against a Chinese or Russian strike involving hundreds or thousands of missiles.

At the request of the subcommittee, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) published estimates May 5 indicating that a system of space-based interceptors would cost between $161 billion and $542 billion over 20 years, depending on requirements and design decisions. The CBO cautioned, however, that these estimates were derived from plans originally formulated to address the threat of “one or two [intercontinental ballistic missiles] ICBMs fired by North Korea.”

Asked May 15 about the upper estimate of $542 billion at the POLITICO 2025 Security Summit, Gen. B. Chance Saltzman, the chief of space operations, said, “I’ve never seen an early estimate that was too high.”

In their May 8 statement, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin characterized the Golden Dome project as a rejection of the “inseparable interrelationship between strategic offensive arms and strategic defensive arms, which is one of the central and fundamental principles of maintaining global strategic stability.”

The statement was issued during a visit by Xi to Moscow to attend commemorations of the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe and the founding of the United Nations.

In past joint statements, the two countries have expressed brief concerns about U.S. missile defense plans. For example, in a June 2019 statement on strengthening contemporary global strategic stability, the two sides said that U.S. missile defense plans would have an “extremely negative effect on international and regional strategic balance, security and stability.”

But the new statement from May 2025 is more specific and much lengthier, outlining concerns that the United States is developing the capability to use “high-precision conventional weapons or a combination of nuclear and non-nuclear weapon systems” to launch a strike against the strategic nuclear forces of Beijing or Moscow. Golden Dome would then, in this hypothetical scenario, intercept a “radically weakened retaliatory strike with air and missile defense assets.”

The aspiration of the United States to “ensure an overwhelming military superiority … fundamentally contradicts the logic underlying the maintenance of strategic balance,” the joint statement claims.

Although China and Russia have missile defense capabilities, neither country has articulated plans for large-scale homeland strategic missile defense. China has tested its Chinese Dongneng-3 interceptor against an intermediate-range target, while Russia maintains a local missile defense system around Moscow that can intercept a limited number of intercontinental ballistic missiles.

The most advanced Russian mobile air and missile defense system, the S-500, is designed to intercept intermediate-range ballistic missiles.

As an Atlantic Council report in February noted, Russian missile defense investments are focused on “protecting Russian leadership, critical command and control, and nuclear forces.”