One day President Donald Trump said he may sell Tomahawks to Ukraine but five days later, he rejected the Ukrainian request.

November 2025

By Xiaodon Liang and Naomi Satoh

After signaling that the United States might transfer Tomahawk cruise missiles to help Ukraine defend against the full-scale Russian invasion, President Donald Trump reversed course, indicating that the Pentagon could not spare its limited stocks of the medium-range weapons.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy asked for the missiles in a Sept. 23 meeting with Trump. (See ACT, October 2025.) Zelenskyy previously had made a similar request in October 2024 as part of a broader proposal to U.S. President Joe Biden, The New York Times reported at the time.

While flying to Israel Oct. 12, Trump told reporters that, “if the war is not settled, we may very well” transfer the missiles. But in a meeting with Zelenskyy in Washington Oct. 17, Trump rejected the request.

The day prior, Russian President Vladimir Putin had spoken with Trump by telephone. The call lasted more than two hours, according to White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt.

Trump’s public vacillations on the Tomahawk missile come as the president attempts to pressure Russia and Ukraine to agree on a ceasefire.

The Wall Street Journal reported Oct. 22 that the White House recently lifted restrictions on U.S. targeting support for Ukraine’s use of shorter-range cruise missiles provided by NATO allies. In response, Trump said the United States has “nothing to do with those missiles,” in a social media post.

The Biden administration lifted the same restrictions in November, but Trump reimposed them after entering office, the Wall Street Journal said. (See ACT, October 2024 and December 2024.)

Trump also imposed sanctions Oct. 22 on the two major Russian oil and gas firms, Rosneft and Lukoil, barring U.S. companies and individuals from transacting with them. The economic impact of this move will hinge on whether the administration next opts for secondary sanctions on foreign actors that buy or trade in Russian oil.

Although Trump announced following his Oct. 16 phone call with Putin that the two leaders would meet in Hungary in roughly two weeks to discuss resolving the war, a lack of progress in talks at the foreign-minister level have left the summit up in the air, CNN reported Oct. 21.

With a range of around 1,600 kilometers, according to its manufacturer, the Tomahawk would be able to reach many targets in European Russia, including Moscow and St. Petersburg.

The transfer of Tomahawk missiles to Ukraine would “signal the advent of a totally new stage in this escalation, including in terms of Russia’s relations with the United States,” Putin said Oct. 2 speaking at the Valdai International Discussion Club in Sochi.

Dmitry Peskov, the Kremlin spokesman, reacted sharply to Trump’s initial suggestion that he might approve the sale in an Oct. 13 state television interview. If “a long-range missile is launched and is flying and we know that it could be nuclear, what should the Russian Federation think?” he asked, according to Reuters.

The last U.S. nuclear-capable Tomahawk, a sea-launched variant, was retired in 2012.

Explaining his subsequent about-face decision to deny the Ukrainian request, Trump noted that “we need Tomahawks for the U.S., too. We have a lot of them, but we need them,” Russian news agency TASS reported.

Estimates of the U.S. stockpile of Tomahawk cruise missiles suggest the president’s concerns are not unfounded. An analysis published Oct. 17 by Mark F. Cancian and Chris H. Park of the Center for Strategic and International Studies assessed that the Pentagon likely has around 1,360 Tomahawks in its arsenal that are not deployed on ships and submarines.

With annual U.S. production in the low double digits and about 20 Tomahawk missiles destroyed each year in tests and training, the Ukrainian proposal “would make Pentagon planners uneasy about depleting too much of the stockpile,” the analysts wrote.

The Pentagon also does not have many options for providing ground-launchers for the Tomahawk, which primarily serves as a ship- and submarine-based weapon with the U.S. Navy. Despite efforts to rapidly field longer-range, ground-launched missiles after the U.S. withdrawal from the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty in 2019, the total number of launchers remains small. (See ACT, May 2024.)

The U.S. Army has produced and equipped troops with two batteries’ worth of Mid-Range Capability Typhon launchers, while the Marine Corps acquired a small number of prototype launchers installed on light vehicles in a separate canceled program. (See ACT, September 2025.)

Despite the Trump administration’s decision to reject Zelenskyy’s request, the United States has been providing assistance to Ukraine’s military campaign against Russian oil and gas industry sites that began this spring, the Financial Times reported Oct. 12. This strategy was intensified after the Aug. 15 Alaska summit between Putin and Trump, according to an Oct. 16 report by CNN.

A BBC investigation found that Ukraine has attacked 21 of Russia’s 38 large petroleum refineries with drones since January, with a sharp rise in attacks in August and September.

Retail oil prices in Russia have increased by 40 percent since January, according to the Oct. 2 BBC report.

Russia has continued launching large-scale drone and missile attacks at Ukraine throughout the year. On Oct. 16, an attack with 300 drones and 37 missiles took Ukrainian gas facilities out of operation, Zelenskyy said in a social media post.

As the two sides advance their missile programs, talks to reduce Korean peninsula tensions seem unlikely.

November 2025

By Kelsey Davenport

North and South Korea are advancing their missile programs as talks to reduce tensions on the Korean peninsula appear unlikely in the coming months.

North Korea displayed a new intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), the Hwasong-20, during its Oct. 11 parade commemorating the 80th anniversary of the Workers’ Party. The state-run Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) described the new system as a “super-powerful strategic attack weapon.”

Following the event, South Korea said it will deploy a powerful conventionally armed ballistic missile, the Hyunmoo-5, which is designed to penetrate buried targets to deter North Korea, by the end of the year.

North Korea has tested ICBMs capable of reaching the continental United States, but the Hwasong-20 is more powerful, according to KCNA.

The three-stage, solid-fueled Hwasong-20 appears similar to the Hwasong-19, a solid-fueled ICBM that North Korea tested in 2024. But the tip of the Hwasong-20 is shaped differently, suggesting that it is designed to carry a different payload, possibly multiple warheads. (See ACT, December 2024.)

North Korea has not flight-tested the Hwasong-20, but it has tested the missile engine, which KCNA described in September

as a “new-type solid-fuel engine using the composite carbon fiber material.”

The Hwasong-20 was transported on an 11-axle transport erector launcher, or TEL, that is similar to the Hwasong-19. North Korea has designed a larger 12-axle TEL that its leader, Kim Jong Un, was pictured with in 2024. The use of the smaller TEL for the Hwasong-20 raises questions about whether North Korea is developing an even larger ICBM that would require the 12-axle TEL.

North Korea also paraded the short-range Hwasong-11E, a nuclear-capable ballistic missile with a hypersonic glide vehicle, for the first time. North Korea has fielded other short-range strategic missiles, but the addition of the hypersonic glide vehicle makes the Hwasong-11E more difficult to intercept using missile defenses.

KCNA described North Korea’s strategic weapons systems as forming the “essence of the military capability for self-defense” and reiterated that the country’s nuclear deterrent “cannot be yielded.” The KCNA commentary echoes Kim’s comments that North Korea will not negotiate with the United States over its nuclear program if the goal is denuclearization.

Top officials from Russia and China attended the anniversary parade and were pictured with Kim.

Prior to the event, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s United Russia Party signed a joint statement with North Korea’s Workers’ Party condemning the “aggressive politics of the West.” In the Oct. 9 statement, the United Russia Party expressed “firm support” for the steps North Korea is taking to “bolster up” defense capabilities. The Workers’ Party reiterated its “full support” for Russia’s “special military operations” in Ukraine.

After the parade, South Korea’s defense minister, Ahn Gyu-back, said that his country is preparing to deploy the Hyunmoo-5, a more powerful conventionally armed short-range ballistic missile. South Korea first displayed the system in 2024.

South Korea has been expanding the range and power of its conventional missile capabilities for more than a decade. Although President Lee Jae-Myung has toned down the rhetoric toward North Korea and called for the resumption of dialogue, he appears poised to continue his predecessors’ investments in South Korea’s military capabilities.

In an Oct. 17 interview with Yonhap News Agency, Ahn described the Hyunmoo-5 as a “bunker buster” that will maintain a “balance of terror” to deter North Korea. The “bunker buster” description refers to the Hyunmoo-5’s penetrating ability, which will allow South Korea to target hardened facilities below ground.

Ahn suggested that South Korea intends to mass-produce the missiles. A salvo of 15-20 Hyunmoo-5 missiles would have a destructive effect similar to a nuclear warhead, he said.

Ahn also said that South Korea is planning a new “next-generation missile system” that will have a “significantly enhanced warhead power and range.” South Korea needs to “significantly increase our arsenal of diverse missiles” to counter North Korea, he said.

During a parliamentary defense committee hearing Oct. 13, Ahn reiterated that South Korea’s focus is deterring the threat posed by North Korea. He pushed back against comments from U.S. officials that U.S. Forces Korea should expand its mission to include deterring China.

Currently, USFK focuses on supporting and training joint U.S.-South Korean forces and the United Nations Command, the multilateral force deployed in South Korea to enforce the 1953 armistice agreement that ended the Korean War.

But U.S. Army Secretary Dan Driscoll told reporters Oct. 1 that USFK should be ready to respond to threats from both North Korea and China, according to Korea/Joong Ahn Daily. The commander of USFK, U.S. Army General Xavier Brunson, said during an Aug. 10 press briefing that USFK must demonstrate “strategic flexibility” in response to the complex regional security environment. He suggested that South Korea and the United States may need to “modernize” the alliance to “go after other things.”

But in his Oct. 13 testimony to the National Assembly Defense Committee, Ahn said he disagreed with Driscoll and insisted that under the status of forces agreement between South Korea and the United States, South Korea will not be involved in a regional conflict “against the will of the Korean people.” South Korea’s “foremost objective must be to counter threats from and around the peninsula,” particularly North Korea, he said.

Persuading Russia and the United States to extend the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty is a major focus as the First Committee meets.

November 2025

By Shizuka Kuramitsu

The UN General Assembly First Committee, which deals with disarmament and international security, is holding its annual meeting under growing pressure, including the fast-approaching expiration of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START). Discussions also are showing the impact of recent UN reforms and Trump administration policy changes on multilateral nuclear negotiations.

At the committee’s 80th session, taking place Oct. 8 to Nov. 7 in New York, states have gathered to discuss and adopt decisions to renew their commitments to advancing disarmament and maintaining international peace and security.

As the committee convened, a Sept. 22 Russian proposal for Russia and the United States to continue adhering to New START’s central limits remained unanswered, despite U.S. President Donald Trump’s brief acknowledgement Oct. 5 that the measure “sounds like a good idea.” (See, ACT, October 2025.) The treaty, the last remaining brake on the two countries’ strategic arsenals, expires Feb. 5.

Moscow seems impatient for a U.S. response. In comments to reporters while on a state visit to Tajikistan Oct. 10, Russian President Vladimir Putin said, “If the Americans decide they don’t need [an informal extension], that’s not a big deal for us.”

Putin and Trump held a lengthy phone call Oct. 16 and announced a forthcoming summit meeting in Hungary, but after preparatory talks by their foreign ministers, the summit appears on hold.

As this First Committee meeting marks the last opportunity for the member states to gather at a multilateral forum on nuclear disarmament issues before New START expires, non-nuclear weapons countries are organizing to support continuation of the treaty.

Austria once again led efforts with 34 other states on a joint statement on the value of U.S.-Russian arms control, calling for the “urgent commencement of negotiations for a successor agreement and … a return to full and mutual compliance with the limits set by the treaty until such time as a successor pact is concluded.”

“We urge both parties to the treaty to spare no efforts in this regard and all other states to be fully supportive,” Austria added.

Due to UN-wide reforms to streamline operations and increase efficiency, known as the UN80 initiative, this year’s First Committee session has fewer meetings and resolutions.

At the general debate Oct. 9, Paul Watzlavick, senior official for the Bureau of Arms Control and Nonproliferation at the U.S. Department of State, said that “the United States is leading by example” to reduce the number of resolutions and costs at the First Committee to “to reinvest efforts in a streamlined, efficient, fit for purpose, arms control and disarmament architecture that more effectively convenes member states to solve problems.”

“We will not introduce any resolutions of our own this year, and we will continue to request others introduce periodicity into many of the annual resolutions that have not substantially changed from year to year, including those that we have both supported and not supported in the past,” said Watzlavick.

Some resolutions reflected changed policies being pushed at the domestic level by the Trump administration. According to foreign delegations speaking anonymously to Arms Control Today, one resolution that is submitted annually to the First Committee this year was missing references to gender and sustainable development goals, two policies Trump opposes. The references were returned to the draft after negotiations.

Similarly, some delegations highlighted a lessened U.S. engagement compared to the previous years.

The First Committee is chaired by Italy’s ambassador to the UN, Maurizio Massari, who said the committee has extra importance this year because it is the last multilateral debate on disarmament before the 2026 nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty Review Conference.

While acknowledging efforts to improve efficiency and streamline processes, Massari promised to “spare no efforts to foster constructive engagement and ensure the full and smooth functioning of the committee with an inclusive, pragmatic, and forward-looking approach aimed at revitalizing the disarmament agenda not as an abstract goal but as a shared imperative for international peace and security.”

“Humanity’s fate cannot be left to an algorithm,” UN Secretary-General António Guterres told participants.

November 2025

By Michael T. Klare

The United Nations has embarked on a major effort to assess the potential risks and benefits of artificial intelligence and to consider possible curbs on its future use.

During a series of meetings in late September, the Security Council and the General Assembly heard from senior government and industry officials on the need for increased international scrutiny of AI and the establishment of international mechanisms for its control.

In the first of these meetings on Sept. 24, the Security Council conducted an open debate on the implications of AI for international peace and security. Chaired by President Lee Jae Myung of South Korea, the event featured briefings by UN Secretary-General António Guterres and Yoshua Bengio, professor of computer science at the Université de Montréal and a leading figure in the field.

“Let us be clear: Humanity’s fate cannot be left to an algorithm,” Guterres told participants in the debate. “Humans must always retain authority over life-and-death decisions.” To prevent unintended consequences, he said, “military uses [of AI] must be clearly regulated through legal reviews, human accountability, and strong safeguards against misuse.”

Other speakers at the debate, including the senior officials of many UN member states, echoed those concerns. Khawaja Muhammad Asif, Pakistan’s minister of defense, noted that the May 2025 conflict between his country and India represents the first instance in which autonomous weapons “were used by one nuclear-armed state against another during a military exchange,” thereby demonstrating “the dangers which AI can pose.”

Many speakers, including Lee and UK Deputy Prime Minister David Lammy, called for adopting formal measures to control the use of AI use for military purposes. However, the principal U.S. delegate at the meeting, Michael Kratsios, the assistant to the president for science and technology, eschewed any sort of international oversight in this area. “We totally reject all efforts by international bodies to assert centralized control and global governance of AI,” he declared.

On the following day, the General Assembly conducted its own debate on AI’s risks and promises. Billed as the initial convocation of a “global dialogue on artificial intelligence governance,” the meeting was designed to enable delegates from UN member states to express their views on the subject.

Unlike the Security Council event, the General Assembly gathering did not consider the military dimensions of AI but focused instead on its social, economic, and scientific implications. Numerous delegates heralded AI’s potential to stimulate economic growth, develop life-saving medicines, and develop new energy sources, but also warned of its capacity to spread misinformation and curb human rights.

To address these issues and consider the possible adoption of measures to ensure the equitable use of AI for positive benefit and prevent its misuse, the General Assembly agreed to sponsor follow-up sessions of the global dialogue in 2026 and 2027. These gatherings, Guterres declared, “will take into account AI’s implications in all its dimensions—social and economic, ethical and technical, cultural and linguistic.”

He also said that the UN would establish an international independent scientific panel on artificial intelligence to be composed of 40 members who will “provide independent insights into the opportunities, risks and impacts associated with AI.”

Friction over Russia’s war against Ukraine and recent alleged incursions by both sides into each other's territory color how the exercises are viewed.

November 2025

By Shaghayegh Chris Rostampour

NATO and Russia conducted separate nuclear-related exercises in October amid heightened tensions driven by Moscow’s prolonged war with Ukraine and recent alleged incursions by both sides into each other’s territories. (See ACT, October 2025.)

NATO held its annual nuclear exercise, “Steadfast Noon,” Oct. 13-24, focusing on procedures for securing and preparing nuclear weapons for potential deployment. According to NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte, the two-week exercise aimed to ensure that the alliance’s nuclear deterrent remains “as credible, and as safe, and as secure, and as effective as possible.” He added in his Oct. 13 announcement that Steadfast Noon “sends a clear signal to any potential adversary that we will and can protect and defend all allies against all threats.”

The exercise involved 14 of NATO’s 32 member states, which contributed about 70 aircraft and 2,000 personnel operating out of airbases in Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, as well as the airspace over the North Sea. Although the training did not include live nuclear weapons, it involved dual-capable fighter jets certified to carry nuclear gravity bombs, as well as conventional support assets to simulate a nuclear scenario.

“These are conventional aircraft or other capabilities that can be used as part of a nuclear mission,” Jim Stokes, the director of NATO’s Nuclear Policy Directorate, said in a statement. “And this demonstrates the overall contribution that allies make, how we share the nuclear burden in different ways, and it really shows the unity we have at the alliance on nuclear issues.”

The exercise featured 13 different types of air assets, including dual-capable fifth-generation fighter jets, surveillance and reconnaissance assets, and refueling aircraft. The United States participated in the drills with four F-35s jets, which for the first time took a leading role as dual-capable aircraft in the “strike package” of the exercise, a term used to describe the simulation of a nuclear strike.

The drill also saw first-time participation by Finland and Sweden, marking a significant step in their integration into NATO’s nuclear planning framework following their respective accession to the alliance in 2023 and 2024. (See ACT, April 2024.) Sweden’s contribution included Gripen fighter jets providing conventional air support, a move that NATO officials said strengthens interoperability and bolsters the alliance’s broader deterrence posture. Finland contributed FA-18 Hornet fighter aircraft and staff officers.

An Oct. 13 NATO press release emphasized that Steadfast Noon is a “routine, long-planned training activity” and “not linked to any current world events.” However, Konstantin Kosachev, deputy chairman of the Russian Federation Council, described it as an “extremely dangerous development.” He told the Russian newspaper Izvestia that the maneuvers can “provoke reactions and retaliatory steps … not only from Russia.”

Meanwhile, Russian armed forces conducted their annual strategic nuclear exercise, dubbed “Grom,” Oct. 22 with land, sea, and air components. Gen. Valery Gerasimov, the chief of the general staff, said in a video report addressing Russian President Vladimir Putin, that the exercises would “practice the procedures for authorizing the use of nuclear weapons” and take a more offensive approach than last year’s exercise, which simulated a “massive nuclear strike in response to a nuclear strike by an adversary.”

Russian media broadcasted the launch of a land-based Yars intercontinental ballistic missile and a Sineva ballistic missile fired from a nuclear-powered submarine. Tu-95MS long-range bombers also fired air-launched cruise missiles, according to a statement by the Russian defense ministry.

Putin, who oversaw the exercise from the National Defense Control Center, emphasized that the maneuvers were scheduled in advance. However, tensions between NATO allies and Russia have been high on several fronts. Moscow recently accused NATO members of direct attacks on Russian territory; NATO has complained of Russian incursions into allied airspace. (See ACT, October 2025.)

U.S. President Donald Trump said recently that he expected to hold a summit with Putin in Budapest, but the meeting appears to be on hold.

Trump Says U.S. Will Resume Nuclear Testing

November 2025

President Donald Trump said the United States would resume nuclear testing after 33 years, a move that could provoke other major nuclear-armed countries to follow suit and accelerate a new arms race.

“We’ve halted [testing] many years ago, but with others doing testing I think it's appropriate to do so,” Trump told reporters Oct. 30 aboard Air Force One.

But on Nov. 2, U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright said the testing ordered by Trump will not involve nuclear explosions at this time.

“I think the tests we’re talking about right now are system tests.... These are what we call non-critical explosions,” he said in an interview with Fox News.

Some 187 countries, including the United States and the four other major nuclear powers, have signed the 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, which bans nuclear weapon testing, and are legally bound to observe it.

U.S. President Bill Clinton voluntarily halted testing in 1992 at the end of the Cold War. The Soviet tested its last nuclear weapon in 1990 and China, in 1996.

Earlier this year Brandon Williams, administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration, told Congress, “I would not advise testing.” He expressed confidence in the scientific experiments and supercomputer simulations that are used instead to ensure U.S. bombs still work.

In this century, only North Korea has conducted a nuclear test explosion and none recently. All such tests are monitored worldwide by the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO).

Robert Floyd, CTBTO executive secretary, said Oct. 30 that ”any nuclear weapon test by any state would be harmful and destabilizing for global nonproliferation efforts and for international peace and security.”

“The CTBTO monitoring system stands ready to detect any such test and provide the data to other CTBT states signatories,” he said in a statement.

Responding to Trump’s announcement on social media, U.S. Rep. Dina Titus (D-Nev.) said: “Absolutely not. I’ll be introducing legislation to put a stop to this.” The Nevada National Security Site, in her home state, is the only place where the United States could do nuclear testing.

Since 1945, there have been 2,056 nuclear test explosions worldwide, 1,030 of which were conducted by the United States.—CAROL GIACOMO

Russia Tests Nuclear-Powered Cruise Missile, Torpedo

November 2025

Russia successfully conducted Oct. 21 the first long-range flight test of the Burevestnik nuclear-powered cruise missile, a Russian military official said. This was followed Oct. 29 by announcement of a test of the Poseidon nuclear-powered and nuclear-capable unmanned underwater vehicle.

The latest Burevestnik test was announced by Gen. Valery Gerasimov, the chief of Russia’s General Staff, at an Oct. 26 meeting with President Vladimir Putin.

Gerasimov said the nuclear-capable missile, which bears the Russian designation 9M730, flew for 14,000 kilometers over 15 hours and “completed all prescribed vertical and horizontal maneuvers, showcasing a high capability to evade missile-defense and air-defense systems,” according to an official transcript of the meeting.

Putin said the Russian armed forces still had to identify a mode of employment for the missile as well as prepare relevant infrastructure. Open-source satellite imagery analyst Decker Eveleth located in September 2024 a possible launch site for the Burevestnik next to a nuclear warhead storage facility at Vologda, nearly 500 kilometers northwest of Moscow.

A Burevestnik protype exploded Aug. 8, 2019, on an off-shore platform at the Nyonoksa missile testing base, killing five scientists. (See ACT, September 2019.)

Putin, visiting a military hospital, announced Oct. 29 that “for the first time, we successfully launched [the Poseidon nuclear-armed torpedo] from a submarine by activating its booster engine, and then started the nuclear reactor, which propelled the apparatus for a certain duration.”

Putin first announced the Burevestnik and Poseidon programs in March 2018, justifying them as a response to the U.S. withdrawal from the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2001 and concerns about U.S. missile defense systems.—XIAODON LIANG AND SHIZUKA KARAMITSU

Russia, Ukraine Agree to Repairs at Zaporizhzhia

November 2025

Ukraine and Russia agreed to a ceasefire around the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant in order to allow workers to repair power lines to the site, the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) announced.

The plant, which Russia is illegally occupying, had been cut off from external power for four weeks when the repairs commenced. Although the six reactor units remain shut down, the facility needs access to external power to cool the reactors and the spent fuel. The last external power line connecting the facility to external power was severed during an attack Sept. 23.

IAEA Director-General Rafael Mariano Grossi said in an Oct. 18 statement on the social media site X that the two sides “engaged constructively” with the agency to enable the repairs. He said the restoration of “off-site power is crucial for nuclear safety and security.”

The repairs, which the IAEA announced were completed Oct. 23, included restoring the main power line to the plant and a backup power line. The backup power line runs through an area still controlled by Ukraine.

The plant relies on diesel generators to produce the electricity necessary for cooling when the external power lines are severed. Grossi, in an Oct. 15 statement, described that situation as “not sustainable.” The IAEA warned that if the diesel generators failed and power was not restored quickly, it could lead to “an accident with the fuel melting and a potential radiation release into the environment.”

The Zaporizhzhia facility has been cut off from external power 10 times since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022.—KELSEY DAVENPORT

Space Force Seeks Space Interceptor Prototypes

November 2025

The U.S. Space Force issued an Oct. 4 request for prototype proposals for space-based interceptors, setting up a competitive award structure for the early stages of the acquisition program.

According to a Sep. 15 report by Breaking Defense, the Pentagon plans to award prizes in the low hundreds of millions of dollars to industry teams that succeed at four milestones: a ground test, two flight tests, and an intercept test by June 2029. The trade press outlet reported skepticism from industry sources that the awards would be large enough incentives.

A request for information issued by the Space Force in June indicated that the service was interested in endoatmospheric interceptors for boost-phase intercept as well as exoatmospheric interceptors for boost-phase or midcourse intercept. The request indicated the project also would include development of ground elements of the space-based interceptor system and fire-control software.

Gen. Michael Guetlein, the Space Force officer appointed to lead the broader Golden Dome effort, briefed Congress twice in September behind closed doors on his newly developed architecture for U.S. missile defense. (See ACT, September 2025.) House and Senate negotiators will decide on reporting and oversight requirements for the missile defense program as they proceed to conference over this year’s defense authorization act, following the Senate’s passage of its bill Oct. 9.

In August, the Defense Department removed nearly 100 programs, including a space-based missile warning constellation, from the oversight purview of the Pentagon’s director of operational test and evaluation. This attracted the attention of Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Rep. Donald Norcross (D-N.J.), who criticized the diminution of the independent testing office’s role in an Oct. 15 letter to Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth.—XIAODON LIANG

Nuclear Ban Treaty Crosses Majority Threshold

November 2025

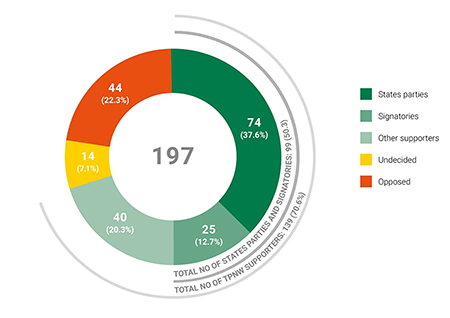

A majority of the world’s countries—99 states—have now signed, ratified, or acceded to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), following Kyrgyzstan’s signature and Ghana’s ratification of the treaty Sept. 26.

The TPNW prohibits states from developing, testing, or acquiring nuclear weapons. It was adopted July 7, 2017, and entered into force Jan. 22, 2021. Currently, 95 states have signed the treaty and 74 have subsequently ratified and become states-parties. Four countries acceded to the treaty without signing beforehand. No nuclear-armed state has become a member.

Kyrgyzstan announced its decision to join the TPNW at an Apr. 30 meeting of the third preparatory committee of the review conference for the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty.

“Kyrgyzstan firmly supports the efforts of the international community to achieve a world free of nuclear weapons,” the delegation’s statement said. “We are committed to ensuring future generations live without the threat posed by weapons of mass destruction.”

Ghana signed the TPNW in September 2017. It participated in the first meeting of states-parties and the Africa Regional Seminar on the TPNW, both in 2022. At the third meeting of states-parties to the TPNW in March, Ghana stated its commitment to ratify the treaty, noting its role as a proponent of the Pelindaba Treaty, which created a nuclear-weapon-free zone in Africa.

The first review conference for the TPNW will take place Nov. 30 to Dec. 4, 2026, in New York; South Africa will preside.—LIPI SHETTY