Volume 11, Issue 8, August 7, 2019

*(Updated Aug. 19)

The 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, negotiated and signed by U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, was one of the most far-reaching and successful nuclear arms reduction agreements in history.

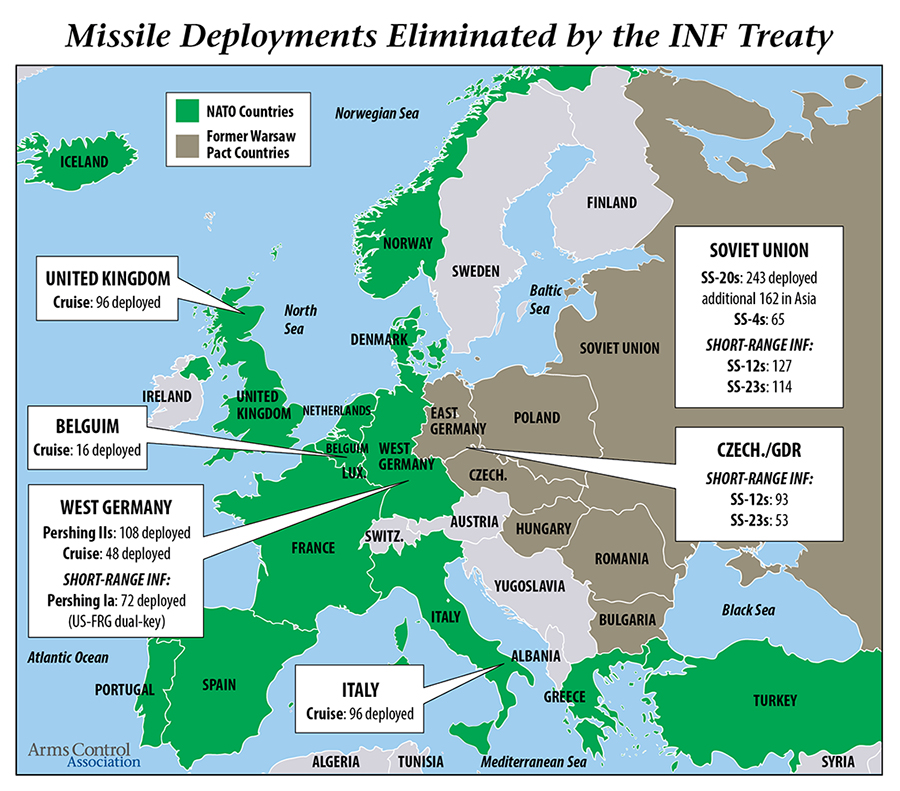

The treaty led to the verifiable elimination of 2,692 U.S. and Soviet missiles based in Europe. It helped bring an end to the Cold War nuclear arms race and paved the way for agreements to slash bloated strategic nuclear arsenals and withdraw thousands of tactical nuclear weapons from forward-deployed areas.

The pact served as an important check on some of the most destabilizing types of nuclear weapons that the United States and Russia could deploy. INF-class missiles, whether nuclear-armed or conventionally armed, are destabilizing because they can strike targets deep inside Russia and in Western Europe with little or no warning. Their short time-to-target capability increases the risk of miscalculation in a crisis.

Despite its success, the treaty has faced problems. A dispute over Russian compliance has festered since 2014, when the United States first alleged a Russian treaty violation, and has worsened since 2017 when Russia began deploying a ground-launched cruise missile, the 9M729, capable of traveling in the treaty’s prohibited 500-5,500 kilometer range.

The Trump administration developed a response strategy in 2017 designed to put pressure on Russia to address the U.S. charges, but in October 2018, President Trump abruptly shifted tactics and announced the United States would leave the agreement.

The Trump administration developed a response strategy in 2017 designed to put pressure on Russia to address the U.S. charges, but in October 2018, President Trump abruptly shifted tactics and announced the United States would leave the agreement.

On Feb. 2, 2019, the Trump administration formally announced that the United States would immediately suspend implementation of the INF Treaty and would withdraw in six months if Russia did not return to compliance by eliminating its 9M729 missile.

On Aug. 2, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declared that Russia was still in “material breach of the treaty” and announced the United States had formally withdrawn from the INF Treaty.

According to The Wall Street Journal, U.S. intelligence agencies have assessed that the Russians possess four battalions of 9M729 missiles (including one test battalion). The missiles are “nuclear-capable,” according to the Director of National Intelligence, but they are probably conventionally armed.

Without the INF Treaty, the potential for a new intermediate-range missile arms race in Europe and beyond becomes increasingly real. Furthermore, in the treaty’s absence, the only legally binding, verifiable limits on the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals come from the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which is due to expire in February 2021 unless Presidents Trump and Putin agree to extend it by up to five years.

Reactions to the U.S. Withdrawal from the INF Treaty

Following the U.S. withdrawal announcement Aug. 2, the Russian Foreign Ministry stated, “The denunciation of the INF Treaty confirms that the U.S. has embarked on destroying all international agreements that do not suit them for one reason or another.”

A few days later, Aug. 5, Russian President Vladimir Putin commented that Moscow will mirror the development of any missiles that the United States makes. “Until the Russian army deploys these weapons, Russia will reliably offset the threats…by relying on the means that we already have,” he said. Putin also ordered “the Defense Ministry, the Foreign Ministry, and the Foreign Intelligence Service to monitor in the most thorough manner future steps taken by the United States.”

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) said in a statement: “A situation whereby the United States fully abides by the treaty, and Russia does not, is not sustainable.”

At the same time, some European countries such as the United Kingdom and Germany have expressed regret over the termination of the treaty and concerns about potential new U.S. missile deployments.

On Aug. 2, German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas said the end of the INF Treaty meant that Europe was “losing part of its security.” Maas also told Germany’s Spiegel Online Jan. 11, 2019: “We cannot allow the result to be a renewed arms race. European security will not be improved by deploying more nuclear-armed, medium-range missiles. I believe that is the wrong answer.”

Also Aug. 2, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg stated that NATO “will respond in a measured and responsible way and continue to ensure credible deterrence and defence.” Stoltenberg suggested that NATO will increase readiness exercises programs; increase intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; and bolster air and missile defenses and conventional capabilities in response to the termination of the INF Treaty.

According to press reports, the NATO response strategy may involve more flights over Europe by U.S. warplanes capable of carrying nuclear warheads, more military training, and the repositioning of U.S. sea-based missiles.

What Missiles Could Each Side Now Deploy in the Absence of the INF Treaty?

With the treaty’s termination, each side is now free to develop, flight test, and possibly deploy previously banned INF-range systems in Europe and in Asia.

President Putin stated Dec. 18 that in the event of U.S. withdrawal from the treaty, Russia would be “forced to take additional measures to strengthen [its] security.” He further warned that Russia could easily conduct research to put air- and sea-launched cruise missile systems “on the ground, if need be.” This could involve additional numbers of the 9M729 ground-launched cruise missile on mobile launchers, as well as its Kaliber sea-based cruise missile system.

Even before the Aug. 2 termination date, the Trump administration was seeking to develop new conventionally armed cruise and ballistic missiles to “counter” Russia’s 9M729 missile. The fiscal year 2018 National Defense Authorization Act, for example, required “a program of record to develop a conventional road-mobile [ground-launched cruise missile] system with a range of between 500 to 5,500 kilometers,” including research and development activities.

Last year, Congress approved a Defense Department request for $48 million in fiscal year 2019 for research and development on concepts and options for conventional, ground-launched, intermediate-range missile systems in response to Russia’s alleged violation of the INF Treaty.

Earlier this year, the Defense Department requested nearly $100 million for fiscal year 2020 to develop three new missile systems that would violate the range limits of the treaty.

One new missile program of interest to the Pentagon is a ground-launched variant of the Air Force’s Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile or the Navy’s Tomahawk sea-based cruise missile. On Aug. 19, the Department of Defense announced it conducted "a flight test of a conventionally-configured ground-launched cruise missile at San Nicolas Island, California. The test missile exited its ground mobile launcher and accurately impacted its target after more than 500 kilometers of flight." The missile was reportedly launched from a Mk. 41 mobile launcher.

Another option under consideration is a new intermediate-range ballistic missile designed to strike targets in China. The day after the formal U.S. withdrawal from the INF treaty, newly confirmed U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper said that he was in favor of deploying conventional ground-launched, intermediate-range missiles in Asia “sooner rather than later,” but “those things tend to take longer than you expect.”

China’s reaction has been negative. “If the U.S. deploys missiles in this part of the world, China will be forced to take countermeasures,” said Fu Cong, director-general of the arms control department at China's foreign ministry, speaking to reporters Aug. 6. “I urge our neighbors to exercise prudence and not to allow the U.S. deployment of intermediate-range missiles on their territory.”

Alternative Risk Reduction Strategies in the Absence of the INF Treaty

Any new U.S. intermediate-range missile deployments would cost billions of dollars and take years to complete. They are also militarily unnecessary to defend NATO allies or U.S. allies in Asia given that existing air- and sea-based weapons systems can already hold key Russian and Chinese targets at risk.

Any U.S. moves to actually deploy these weapons are likely to prompt Russian and Chinese countermoves and vice-versa. The result could be a dangerous and costly new U.S.-Russian and U.S.-Chinese missile competition.

Therefore, the U.S. Congress can and should step forward to block funding for U.S. weapons systems that could provoke a new missile race—and provide the time needed to put in place effective arms control solutions.

In January 2019, 11 U.S. senators reintroduced the “Prevention of Arms Race Act of 2019,” which would prohibit funding for the procurement, flight-testing, or deployment of a U.S. ground-launched or ballistic missile—with a range between 500 and 5,500 kilometers—until the Trump administration provides a report that meets seven specific conditions. These include identifying a U.S. ally formally willing to host such a system and, in the case of a European country, demanding that all NATO countries agree to that ally hosting the system.

In July, the House of Representatives narrowly approved an amendment introduced by Rep. Lois Frankel (D-Fla.) to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for fiscal year 2020. The amendment prohibits funding for missile systems noncompliant with the INF Treaty unless the Trump administration demonstrates that it exhausted all potential strategic and diplomatic alternatives to withdrawing from the treaty and unless the Secretary of Defense meets certain conditions.

In addition, with the end of the INF Treaty now official, it is critical that President Trump, President Putin, and NATO leaders explore more seriously some arms control arrangements to prevent a destabilizing new missile race:

- One option would be for NATO to declare, as a bloc, that no alliance members will field any missiles in Europe that would have been banned by the INF Treaty so long as Russia does not field once-prohibited systems that can reach NATO territory. This would require Russia to remove its 50 or so 9M729 missiles that have been deployed in western Russia.

The United States and Russian presidents could agree to this “no-first INF missile deployment plan” through an executive agreement that would be verified through national technical means of intelligence. Russia could be expected to insist upon additional confidence-building measures to ensure that the United States would not place offensive missiles in the Mk 41 missile-interceptor launchers now deployed in Romania as part of the Aegis Ashore system and, soon, in Poland. (Russian officials have long complained to their U.S. counterparts about the missile-defense batteries’ dual capabilities.)

This approach would also mean forgoing President Trump’s plans for a new ground-launched, conventionally armed cruise missile. Because the United States and its NATO allies can already deploy air- and sea-launched systems that can threaten key Russian targets, there is no military need for such a system.

- Another possible approach would be to negotiate a new agreement that verifiably prohibits ground-launched, intermediate-range ballistic or cruise missiles armed with nuclear warheads. As a recent United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research study explains, the sophisticated verification procedures and technologies already in place under New START can be applied with almost no modification to verify the absence of nuclear warheads deployed on shorter-range missiles. Such an approach would require additional declarations and inspections of any ground-launched, INF Treaty-range systems. To be of lasting value, such a framework would require that Moscow and Washington agree to extend New START by five years.

- A third variation would be for Russia and NATO to commit reciprocally to each other—ideally including a means of verifying the commitment—that neither will deploy land-based, intermediate-range ballistic missiles or nuclear-armed cruise missiles (of any range) capable of striking each other’s territory.

INF Termination Is Bad. Failure to Extend New START Would Be Worse.

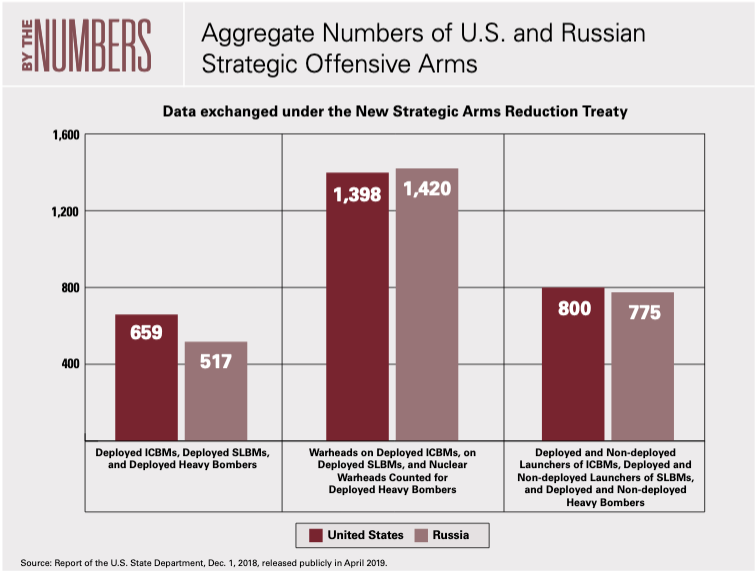

With the collapse of the INF Treaty, the only remaining agreement regulating the world’s two largest nuclear stockpiles is New START. Signed in 2010, this treaty limits the two sides’ long-range missiles and bombers and caps the warheads they carry to no more than 1,550 each. It is due to expire Feb. 5, 2021, unless Presidents Trump and Putin agree to extend it for up to five years, as allowed for in the treaty text.

With the collapse of the INF Treaty, the only remaining agreement regulating the world’s two largest nuclear stockpiles is New START. Signed in 2010, this treaty limits the two sides’ long-range missiles and bombers and caps the warheads they carry to no more than 1,550 each. It is due to expire Feb. 5, 2021, unless Presidents Trump and Putin agree to extend it for up to five years, as allowed for in the treaty text.

Key Republican and Democratic senators, former U.S. military commanders, and U.S. NATO allies are on the record in support of the treaty’s extension, which can be accomplished without further Senate or Duma approval.

In addition, the NDAA for fiscal year 2020 includes bipartisan efforts to preserve New START. The House bill includes legislation proposed by Chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee Eliot Engel (D-N.Y.) and the committee’s ranking member, Rep. Michael McCaul (R-Texas), for the administration to extend New START and require reports from the secretaries of state and defense plus the director of national intelligence on the possible consequences of the treaty’s lapse. For its part, the Senate version of the NDAA does not include an provision calling for the extension of the treaty, though in May, a bipartisan group of senators introduced a resolution calling for the administration to consider an extension of New START and begin discussions with Russia. On Aug. 1, Sens. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.) and Todd Young (R-Ind.) also introduced legislation calling for an extension of New START until 2026.

Unfortunately, U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton may be trying to sabotage this treaty. Since arriving at the White House in April, he has been slow-rolling an interagency review on whether to extend New START and refusing to take up Putin’s offer to begin extension talks. In June, Bolton also said in an interview with The Washington Free Beacon that “there’s no decision, but I think it’s unlikely” that the administration will move to extend the treaty. In late July, he further said that the treaty “was flawed from the beginning” and that, “while no decision has been made,” the administration needs “to focus on something better.”

Extension talks should begin now in order to resolve outstanding implementation concerns that could delay the treaty’s extension.

Without New START, there would be no legally binding limits on the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals for the first time since 1972. Both countries would then be in violation of their Article VI nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty obligation to “pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament.”

Bottom Line

Without the INF Treaty and without serious talks and new proposals from Washington and Moscow, Congress as well as other nations will need to step forward with creative and pragmatic solutions that create the conditions necessary in order to ensure that the world’s two largest nuclear actors meet their legal obligations to end the arms race and advance progress on nuclear disarmament.—DARYL G. KIMBALL, executive director, and SHANNON BUGOS, research assistant