“For 50 years, the Arms Control Association has educated citizens around the world to help create broad support for U.S.-led arms control and nonproliferation achievements.”

March 2023

Edition Date

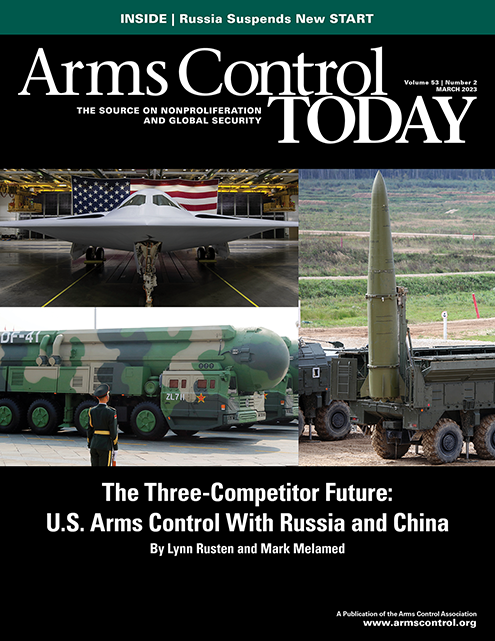

Cover Image

March 2, 2023

March 1, 2023

March 1, 2023

March 1, 2023

March 1, 2023

March 1, 2023

March 1, 2023

March 1, 2023

March 1, 2023

March 1, 2023

March 1, 2023

March 1, 2023

March 1, 2023

March 1, 2023

March 1, 2023

March 1, 2023