U.S., Russia Disagree on Prospect for Arms Control Deal

Against the backdrop of the imminent U.S. presidential election and the impending expiration in less than four months of the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), the Trump administration appears to have once again shifted its proposal for an arms control framework deal with Russia.

But despite U.S. claims of progress in recent talks, Russia continues to strongly reject the proposed U.S. framework and to call for extending New START by five years without conditions as allowed by the treaty.

U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Arms Control Marshall Billingslea said Oct. 13 that in exchange for Russia agreeing to a freeze on the total U.S. and Russian nuclear warhead stockpiles, including non-strategic warheads, the United States would “extend the New START treaty for some period of time.”

Billingslea added that the Trump administration has proposed verification “measures that would give some confidence” that Russia is “abiding by a freeze.” He also said that “everything we agree with the Russians must be framed and must be formatted in a way that allows us to extend that arrangement to the Chinese when they finally are brought to the negotiating table.”

In August, Billingslea conditioned U.S. consideration of a short-term extension of New START on Russia agreeing to a politically binding framework deal that would cover all nuclear warheads, make changes to the New START verification regime, and be structured to include China in the future. The Trump administration had earlier insisted that China immediately participate in trilateral arms control talks with the United States and Russia.

According to Billingslea, the administration believes “that there is an agreement in principle at the highest levels of our two governments” on the latest U.S. proposal, but that this “gentleman’s agreement…will ultimately need to percolate down through their [the Russian] system so that my counterpart hopefully will be authorized to negotiate.”

The upbeat U.S. characterization of the status of the talks with Moscow follows meetings between Billingslea and Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov in Helsinki Oct. 5, and National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien and Russian Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev in Geneva Oct. 2.

O’Brien said Oct. 5 that “we would like to see a good arms control deal, not a fake arms control deal, but a real one that has verification.” He added that “we’ve come to a logjam in our meetings with the Russians on New Start” and his meeting with Patrushev was in part designed “to break the logjam.”

Russia Disagrees

Russia has poured cold water on the U.S. claims of progress in the talks and an agreement in principle on a warhead freeze.

The Russian Foreign Ministry called the U.S. characterization of the talks a “delusion.”

Ryabkov said the U.S. freeze proposal was “unacceptable for us” and “needs to be tackled together” with other strategic stability issues such as “delivery vehicles, space, U.S.-made missile defense, and their growing non-nuclear strategic offensive arms arsenals.”

“If the U.S. side wants to report to their leadership that they allegedly agreed on something with Russia prior to their elections, they’re not getting that,” he added.

Russian Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova made similar comments Oct. 8, saying that “it would be premature to say that we have made a big step towards a tangible result.”

“There is still much to be done to bring our positions closer together and to find possible points of agreement,” she said. Moscow believes that New START should be extended for five years while “a new strategic equation that would take into account the most important aspects of national security and strategic stability” is hammered out, she added.

Overall, Russia is skeptical that the United States will agree to an extension of New START, which expires in February 2021 unless the presidents of the United States and Russia both agree to extend it by a period of up to five years. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said Oct. 5 that New START “is going to die” and that the U.S. conditions for its extension are “absolutely unilateral.”

Asked to reconcile the different U.S. and Russian interpretations of the status of the talks, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo told reporters Oct. 14 that the administration “would welcome the opportunity to complete an agreement based on understandings that were achieved over the last couple weeks about what the range of possibilities look like for an extension of New START.”

Several key details about the U.S. framework proposal have yet to be clarified by the Trump administration. These include the specific warhead types that would be captured by the freeze, the scope of the measures to verify the freeze, the number of years New START would be extended, whether the framework document must explicitly reference the need to include China in the future, and whether the framework document would include reference to longstanding Russian conditions for making further progress on arms control beyond New START.

According to an Oct. 5 Wall Street Journal report, a senior U.S. official said that the Trump administration would link the freeze to an extension of New START. A person familiar with the discussions told the Journal Oct. 9 that the administration hopes to negotiate an agreement before the Nov. 3 presidential election and that the freeze would be paired with and last for as long as New START is extended.

After months of insisting that there was plenty of time to decide on whether the extend New START, Trump administration officials are now warning that time is running out.

“We don’t really have a lot of time,” said U.S. Ambassador to Russia John Sullivan Oct. 1. “The clock is ticking.”

Barring a last-minute breakthrough over the next few weeks, the fate of New START is likely to be decided by the U.S. presidential election on Nov. 3. Former vice president Joe Biden, the Democratic nominee, has previously said that he supports a five-year extension of the accord.

Putin said Oct. 7 that talks on New START extension or “a new strategic offensive reductions treaty” could be “a very serious element of our potential collaboration in the future.”

Billingslea warned last month that if Russia does not agree to a broader framework deal before the U.S. presidential election, the cost for Russia to secure an extension of New START could rise. He asserted that if the talks with Russia fail, the Trump administration would be “extremely happy” to allow New START to expire and immediately move to build up the U.S. nuclear arsenal following its expiration in February.

New START caps the U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals at 1,550 deployed warheads and 700 deployed missiles and heavy bombers each. According to the latest exchange of data Oct. 1, which is the last exchange to take place before the treaty’s expiration date, both the United States and Russia are at or below the New START limits.—KINGSTON REIF, director for disarmament and threat reduction policy, and SHANNON BUGOS, research assistant

NEW START

Congress, U.S. Allies Emphasize Need for New START Extension

Support for a five-year extension of New START among members of Congress and U.S. allies has continued to grow as the date of its potential expiration approaches.

The bipartisan Future of Defense Task Force, co-chaired by Reps. Seth Moulton (D-Mass.) and Jim Banks (R-Ind.) emphasized the need for New START’s extension in its final report released Sept. 29. “With a rapidly approaching expiration date, the United States and Russia should extend the highly successful Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) while negotiating a follow-on agreement,” the report said.

The task force was comprised of members of the House Armed Services Committee from both parties: Reps. Susan Davis (D-Calif.), Chrissy Houlahan (D-Pa.), Elissa Slotkin (D-Mich.), Scott DesJarlais (R-Tenn.), Paul Mitchell (R-Mich.), and Michael Waltz (R-Fla.)

Meanwhile, Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Lofven used his Sept. 26 address at the United Nations General Assembly to “call on the United States and Russia to agree on an extension of the New START Treaty and on China to join discussions on follow-on arrangements.”

The European Leadership Network released an Oct. 13 letter to Congress from a group of over 75 European parliamentarians from more than 20 European capitals, the European Parliament, and NATO Parliamentary Assembly expressing their “interest in cooperating with you in urging the U.S. government to agree to the extension of New START.”

“While Europe did not participate in New START’s negotiations, it is both a beneficiary of the stability brought by the Treaty and a potential victim of much greater uncertainty and danger if it disappears,” they wrote.

U.S. allies are worried about the possible ramifications of a lapse of New START, according to an internal State Department report to Congress obtained by Foreign Policy Sept. 24.

While sharing concerns about “the development and deployment of new Chinese and Russian nuclear capabilities and the termination of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty due to Russia’s longstanding violation and refusal to return to compliance,” U.S. allies and partners are “also concerned about the potential repercussions to the international security environment should New START expire before its full term,” said the report.

STRATEGIC STABILITY

Outstanding Issues on Open Skies Treaty Post U.S. Exit, Russia Says

Russia earlier this month emphasized its concerns with how the remaining states-parties to the 1992 Open Skies Treaty will handle information obtained under the treaty following the expected official U.S. withdrawal next month.

During the fourth review conference for the treaty beginning Oct. 7, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov said that U.S. allies who remain party to the Open Skies Treaty will face “a conflict of obligations.” Once the United States completes its withdrawal, Moscow is concerned that Washington will be able to maintain access to information received via the treaty through its allies who remain states-parties, particularly those who are members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Ryabkov specifically pointed to Article IX of the treaty, which stipulates that all information gathered during overflights be made available to any of the states-parties and be used exclusively for achieving the objectives of the treaty. The treaty’s provisions that restrict the data to only states-parties, Ryabkov argued, should be prioritized.

Ryabkov said Russia has proposed that U.S. allies express their commitment to upholding the treaty’s provisions through the exchanging of diplomatic notes but has been “disappointed” in the reaction of other treaty members to this proposal.

“A lack of willingness to clearly reaffirm their contractual obligations raises serious concerns about their true intentions,” he said. “The conversation on this topic is not over.”

In his remarks, Ryabkov said that Moscow has recently shown goodwill under the treaty, for example, with the Feb. 2020 flight over Kaliningrad that exceeded the 500-kilometer sublimit Russia has imposed since 2014. He then alleged that Canada, France, Lithuania, Poland, and the United Kingdom as states-parties have “impede[d] the normal functioning of the treaty.

The review conference was chaired by Belgium, which in a press release pledged that during the proceedings, it would “make room for a constructive open dialogue with the aim of reaffirming the importance of the ‘Open Skies’ treaty and the engagement of States parties to continue to implement the treaty.”

Before the review conference, Germany moderated an Oct. 5 discussion on “the Quota Coordination and Deconfliction for Open Skies Flights in 2021.” According to Ryabkov, the distribution of quotas was successful.

Signed in 1992 and entered into force in 2002, the Open Skies Treaty permits the 34 states-parties to conduct short-notice, unarmed, observation flights over the others’ entire territories to collect data on military forces and activities. In May 2020, the Trump administration announced that the United States will withdraw from the treaty in six months due to concerns with Russian compliance and implementation. The states-parties met in July to plot the course forward after November.

Since it entered into force, the Open Skies Treaty has allowed for 1,534 observation flights, said Belgium.

FACT FILE

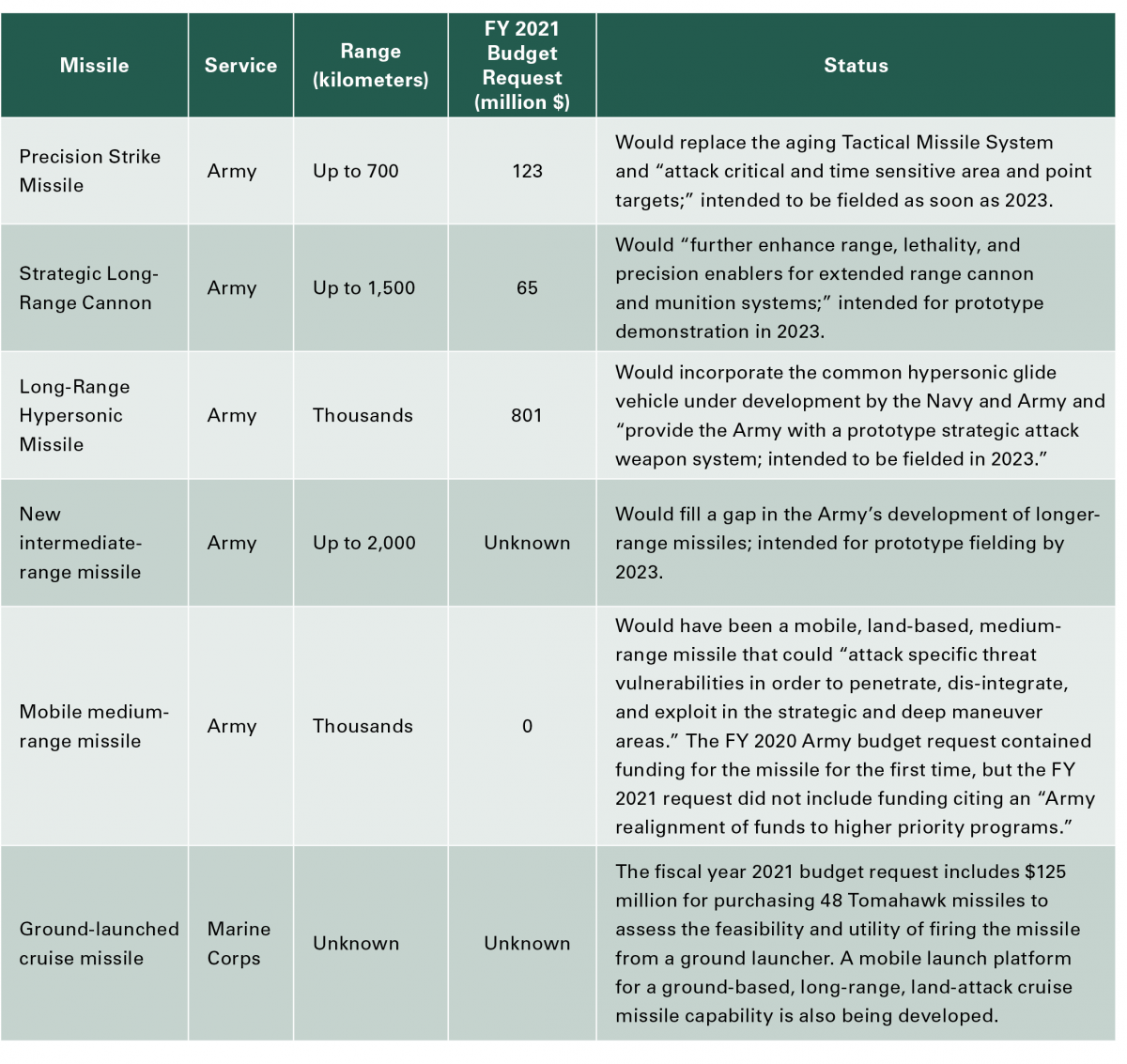

U.S. Ground-Launched Missiles With a Range Formally Prohibited by the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty

NEW RESOURCES & ANALYSES

- “Saving the Open Skies Treaty: Challenges and possible scenarios after the U.S. withdrawal,” by Alexander Graef, European Leadership Network, Sept. 22, 2020

- “To Deter China, Extend New START,” by Alex Moore, Defense News, Sept. 22, 2020

- “Rearming Arms Control Should Start with New START Extension,” by Jim Golby, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Sept. 23, 2020

- “Washington’s Arms Control Delusions and Bluffs,” by Steven Pifer, Defense One, Sept. 28, 2020

- “At 11th Hour, New START Data Reaffirms Importance of Extending Treaty,” by Hans Kristensen, Federation of American Scientists, Oct. 1, 2020

- “A ReSTART for U.S.-Russian Nuclear Arms Control: Enhancing Security Through Cooperation,” by Pranay Vaddi and James Acton, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Oct. 2, 2020

- “Extending New START for Five Years,” by Michael Krepon, Arms Control Wonk, Oct. 4, 2020

- “We Need to Build on the New START Treaty,” by Lynn Rusten, The Wall Street Journal, Oct. 6, 2020

- “Practical Ways to Promote U.S.-China Arms Control Cooperation,” by Tong Zhao, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Oct. 7, 2020

- “Time Running Out: Extend New START Now,” by Kingston Reif and Shannon Bugos, Arms Control Association, Oct. 7, 2020

- “BRIEFING: “Trump's Effort to Sabotage New START and the Risk of an All-Out Arms Race,’” featuring Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.), Alexandra Bell, and Daryl Kimball, Arms Control Association, Oct. 9, 2020

- “US approach to Open Skies and New START endangers strategic stability,” the House of Lords International Relations and Defense Committee, UK Parliament, Oct. 12, 2020

ON OUR CALENDAR

| Nov. 3 | Election Day in the United States |

| Nov. 6 | Conference on Capturing Technology and Rethinking Arms Control, hosted by German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas, Berlin |

| Nov. 21-22 | G-20 Summit, Riyadh (virtual) |

| Dec. 8 | 33rd anniversary of the signing of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty |