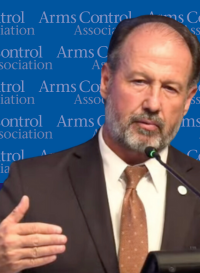

Daryl G. Kimball, Executive Director

|

| Daryl G. Kimball [email protected] 202-463-8270 ext. 107   |

Daryl G. Kimball has been Executive Director of the Arms Control Association (ACA) and publisher and contributor for the organization’s monthly journal, Arms Control Today, since September 2001.

For more than two decades at ACA, Kimball has led the organization’s education, research, and policy advocacy campaigns on a range of issues, including cancellation of new nuclear weapons programs, negotiation and ratification of the 2010 New START agreement, opposition to the controversial U.S.-India nuclear cooperation agreement, the conclusion of the 2015 P5+1 nuclear deal with Iran, efforts to promote entry into force of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty and strengthen implementation of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, the negotiation of the 2014 Arms Trade Treaty, and strengthening the taboo against chemical weapons. He is a frequent expert source for reporters and policymakers, and has written and spoken extensively about nuclear arms control, disarmament, non-proliferation, and the effects of weapons production, testing, and use. In 2004, National Journal recognized him as one of the ten key individuals whose ideas will help shape the policy debate on the future of nuclear weapons. In 2011, the MacArthur Foundation recognized ACA as an “exceptional organization that effectively addresses pressing national and international challenges with an impact that is disproportionate to its small size."

From 1997 to 2001, he was the executive director of the Coalition to Reduce Nuclear Dangers, a consortium of 17 of the largest U.S. non-governmental organizations working together to strengthen national and international security by reducing the threats posed by nuclear weapons. While at the Coalition, Daryl coordinated community-wide education, research and lobbying campaigns for the CTBT, further deep and verifiable reductions in nuclear weapons stockpiles, and against the deployment of an unproven and ineffective national missile defense system.

From 1989-1997, Kimball worked as the Associate Director for Policy and later, the Director of Security Programs for Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR), where he organized media, lobbying and public education campaigns against nuclear weapons production and testing, and research projects on the health and environmental impacts of the nuclear arms race. His work helped to expose and accelerate the cleanup of a toxic, Cold War-era nuclear weapons production site in his hometown of Oxford, Ohio. Through PSR, Daryl also spearheaded non-governmental efforts to win Congressional approval for the 1992 nuclear test moratorium legislation, to extend the test moratorium in 1993, to win U.S. support for a “zero-yield” test ban treaty, and for the U.N.’s endorsement of the CTBT in 1996.

Kimball was a former Herbert R. Scoville Peace Fellow (1989), a graduate of Miami University of Ohio (1986), where he received his B.A. in Political Science and Diplomacy/Foreign Affairs, and was the recipient of the Ohio Governor’s Youth Award for Peace (1985).

Recent Publications and Citations