Jul/Aug 2025 - Energy Dept. budget news

U.S. Energy Department to Reshuffle Warhead Budgets

By Lipi Shetty in Arms Control Today

By Lipi Shetty in Arms Control Today

By Xiaodon Liang in Arms Control Today

By Kelsey Davenport in Arms Control Today

July/August 2025 Digital Magazine

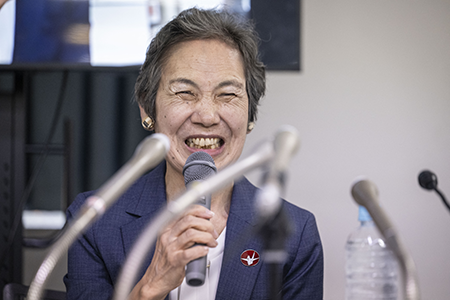

A survivor of the U.S. nuclear attack on Nagasaki shares memories and lessons from that fateful day as geopolitical instability and the threat of nuclear weapons use are again on the rise.

July/August 2025

By Masako Wada

I was one year and ten months old when Nagasaki was devastated by the atomic bomb. I was inside my house, located 1.8 miles away from the blast center. Thanks to the mountains surrounding the central part of Nagasaki City, which somewhat shielded my house from the direct impact of the bomb, I did not suffer any burns or injuries and have survived to this day. As I was only a baby then, I do not personally remember anything about that time, nor can I tell you firsthand of the indescribable tragedies that our senior hibakusha—as survivors of the bombings are known—witnessed and experienced on that day and in the aftermath. But I certainly was there, together with my grandfather and mother, who told me about those horrors over and over again.

It was a very hot day August 9, 1945. My mother, Shizuko Nagae, was preparing lunch out of the meager ingredients she had gathered. An air-raid warning that sounded in the morning had been lifted. I was playing alone in front of the house. She said to me, “Come in. It’s too hot outside,” so I went inside. It was a usual prelunch time in a quiet residential area.

Suddenly, she heard a tremendous sound. She did not immediately understand what happened. When she was able to focus, she found that a one-foot pile of dust and debris had accumulated inside the house, which was south of the blast center in Nagasaki’s Urakami district. The pile was composed of shattered windowpanes, sliding doors, and clay house walls. The lush green mountains surrounding the city had turned brown.

After a while, my mother saw a startling sight. People escaping the fire from Urakami, seeking water and medical help, streamed over Mount Kompira to the urban area where our house was located. From a distance, the people staggering down the mountain looked like a line of ants, but in fact, they were rows of burned and injured, chocolate-colored human beings. They wore little or no clothing, and their hair was bloodied and matted like horns.

In the space next to our house—a vacant lot created by prematurely demolishing houses to prevent the spread of fire during air raids—cremations took place day after day. The smell made it impossible for her to eat anything. The corpses of the victims were brought in, one after another, on box-shaped garbage carts. Survivors who collected bodies from the roadside grabbed the limbs and threw them into the garbage carts. It seemed so casual. Burned limbs were sticking out of the carts like dolls. People initially talked about how many or how few new bodies they encountered each day, but eventually they stopped feeling anything at all about what they witnessed. The bodies were burned like garbage. What is human dignity? Should human beings be treated like that? My mother used to tell me that every August after the war, memories of those ghastly images and the smell that accompanied them would come back to her.

August 15, the day the war ended, my mother was sent to a temporary relief station. She helped to medically treat people who had been taken in for burns and other injuries. The sight of wounded people lying body to body on the auditorium floor was beyond description. My mother was assigned to follow the doctor from patient to patient, carrying antiseptic solution, but some wounds were so severe that she passed out on the spot. Once she came to her senses, she was relegated to cleanup work. She had to use a broom to sweep away the maggots that were swarming all over the survivors’ festering wounds. The maggots were as big as her thumb. She had never seen maggots that big and in such large numbers and hoped she would never see them in the future.

August 15, the day the war ended, my mother was sent to a temporary relief station. She helped to medically treat people who had been taken in for burns and other injuries. The sight of wounded people lying body to body on the auditorium floor was beyond description. My mother was assigned to follow the doctor from patient to patient, carrying antiseptic solution, but some wounds were so severe that she passed out on the spot. Once she came to her senses, she was relegated to cleanup work. She had to use a broom to sweep away the maggots that were swarming all over the survivors’ festering wounds. The maggots were as big as her thumb. She had never seen maggots that big and in such large numbers and hoped she would never see them in the future.

Japanese people were not the only victims; there also were Koreans, Chinese, and Allied forces prisoners of war. These were people, regardless of nationality or race, who happened to be in Nagasaki on that fateful day, away from their homes. At the time of the bombing, the U.S. military also dropped a radio sensor machine by parachute to report on the conditions of the dropped bombs. “Didn’t the machine attached to the parachute tell the U.S. military anything other than about the atomic bomb?” my mother asked. “Didn’t it tell them about the lives of the people under that mushroom cloud, about their families, and above all, about the preciousness of life?”

U.S. Brig. Gen. Thomas Farrell, the deputy commanding general of the Manhattan Project, arrived in Japan shortly after the atomic bombing and told a press conference, effectively, that all those who were doomed to die had died, and there was no one suffering from radiation. As a result, all the temporary relief stations were closed.

In Japan, a defeated nation, reporting on the damage caused by the atomic bombing was severely restricted by the United States. Many people died without knowing why they were dying. By the end of December 1945, the number of dead within concentric circles from the hypocenter of the blast was estimated at 140,000 in Hiroshima and 90,000 in Nagasaki. Sixty-five percent of the victims were children, women, and the elderly; only 4 percent of them died while being cared for by someone. Many of the dead were burned like garbage without being identified by name or hometown. Those who were cremated by their families, and thus had been identified, may have been the fortunate ones.

Survivors were never informed of the causes of their wounds and suffering. They were tormented by survivors’ guilt, illness, and poverty, and had to give up many of their dreams. They also were subjected to discrimination and prejudice because of the lack of understanding in society. For nine years following the atomic bombings, survivors were abandoned by the Japanese government and the United States, with no medical care or assistance extended to them.

After the United States tested a hydrogen bomb near Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands in 1954, “ashes of death” spread across a vast area and a Japanese fishing crew was exposed to the radioactive fallout. Their radioactive catch was called “A-bomb tuna.” Now aware of the dangers and horrors of radiation, Japanese citizens started a signature campaign calling for a total ban on nuclear weapons. The movement spread like wildfire across Japan, gathering more than 30 million signatures and leading to the first World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. Hibakusha, who had been forced to live in silence and in hiding until then, came out in the open and let their voices be heard. Consequently, in 1956, 11 years after the atomic bombing, hibakusha founded Nihon Hidankyo, the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations.

“Message to the World,” the founding declaration of Nihon Hidankyo, stated: “We have reassured our will to save humanity from its crisis through the lessons learned from our experiences, while at the same time saving ourselves.” The hibakusha’s physical and emotional wounds were not yet healed and they were still feeling as if putting these wounds into words would take them back to that traumatic moment in 1945 when the world was upended. But their pledge—that they do not want anyone else to go through the same cruel experience that they did—is very touching and inspiring.

Since its establishment 69 years ago, Nihon Hidankyo has been calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons, which have brought about only inhumane consequences and still cause aftereffects, leaving scars on our lives, bodies, and minds. Furthermore, these weapons continue to cause anxiety in our children and grandchildren. Nuclear weapons impose indiscriminate, extensive damage by means of blasts, heat rays, and radioactivity, and their aftereffects persist for decades. If used again, they would inflict the same suffering experienced by the hibakusha on many other people around the world.

My mother died 14 years ago at age 89. She was in and out of hospital 28 times due to numerous illnesses, including stomach cancer and liver cancer. Before she died, I once recorded in writing what she witnessed, but she seemed quite dissatisfied with what she read. “It was nothing like that,” she said, letting her words trail off. She might have felt that no words or expressions could describe the hellish scenes and experiences she had witnessed.

Other senior hibakusha must feel as she did. I am always hesitant to share my mother’s experience with other people, as I know I can never fully describe what really happened. But now that so many years have passed and the average age of the survivors has reached 86, we younger hibakusha must carry on their work and speak out forcefully on their behalf.

With the adoption of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) in 2017, a heavy and rusty door has begun to open, and we are finally seeing a ray of light illuminating a path to achieve our goal.

Hibakusha have testified on their experiences across the world despite the painful memories of those two days in 1945. We note the term “public conscience” in the TPNW preamble. Public conscience is essential for securing benefits for the public, the human race, and Mother Earth. Power is not justice. Nuclear weapons are an injustice that must be abolished by the humans who are responsible for having invented them. We must continue to urge the nuclear-armed states and their allies, including Japan, to sign and ratify the TPNW to save humanity from its crisis.

Because of the atomic bombings, we attach special significance to strongly urging the Japanese government to sign and ratify this treaty, which it still refuses to do. Japan has forsaken nuclear weapons, but the nuclear weapons arsenals of the United States, Russia, and other nuclear-armed states are said to be many times more powerful than the ones used in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In today’s unstable world, the risk of nuclear weapons use is the highest since the end of the Cold War. What will happen to Earth, the climate, and the human race if we engage in nuclear exchanges? It is more urgent than ever to think seriously about nuclear weapons and the global crisis. As citizens, we must strengthen our demands to the governments. All states must sign and ratify the TPNW. They should know that nuclear weapons, humanity, and Earth cannot coexist.

Nihon Hidankyo was awarded the 2024 Nobel Peace Prize based on certain criteria, namely that the laureate shall have done the most or the best work for “fraternity among nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies, and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.” That is exactly what Nihon Hidankyo has been doing since its founding.

As Norwegian Nobel Committee Chairman Jorgen Frydnes, who was born long after the war, stated at last year’s awards ceremony: “Nihon Hidankyo and the Hibakusha … have never wavered in their efforts to erect a worldwide moral and legal bulwark against the use of nuclear weapons. Their role in establishing the taboo is unique. Their personal stories humanize history, lifting the veil of forgetfulness and drawing us out of our daily routines. They bridge the gap between ‘those who were there’ and we others untouched by the violence of the past. They are living reminders of what is at stake.”

The committee evaluated the work of each hibakusha who, by sharing experiences and witness accounts, conveyed to people the inhuman consequences of nuclear weapons. The committee further emphasized the significance of this mission at a time of geopolitical tension, when the threshold for nuclear weapons use has been lowered.

Last August 5 at a meeting in Hiroshima, Izumi Nakamitsu, the UN high representative for disarmament affairs, told us that even in the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty preparatory committee meetings, statements that presuppose the eventual use of nuclear weapons, which had never been made before, are now openly heard. The threshold for the use of nuclear weapons indeed has been lowered.

I do not believe in security through the nuclear umbrella. With such a broken umbrella, I do not believe that the lives, property, and livelihoods of the people of Japan can be protected. When we met with Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba January 8, 2025, he mentioned the construction of a nuclear shelter. But for whom? Does he really think that will save us?

Frydnes emphasized that younger generations are carrying forward the experiences and the message of the hibakusha. But it is necessary that civil society as a whole, not only younger generations, should raise their voices on behalf of the hibakusha.

As of March 2024, the number of surviving hibakusha was 106,000. Every year, about 6,000 to 10,000 hibakusha pass away. The day when there will be no more hibakusha is not far off. But before that happens, I fear that a new generation of hibakusha may be born. Some say that World War III could soon begin.

I believe that the Nobel Committee decided to award the prize to Nihan Hidankyo, recognizing that the existence of the hibakusha and their words, not nuclear weapons, have been a deterrent to nuclear war. I am happy that the term “Nihon Hidankyo” has become known in Japan and abroad. Receiving the award was not our goal, but it has provided a new boost for our mission.

The hibakusha are the ones who know the humanitarian consequences of the use of nuclear weapons. We will continue to convey that reality. Please listen to us, please empathize with us. Find out what you can do and take action together with us. Nuclear weapons cannot coexist with human beings. They were created by humans; let us assume the responsibility to abolish them with the wisdom of public conscience.

Sherman, the former U.S. deputy secretary of state, says “we must persist” in pursuing a diplomatic solution to the impasse over Iran’s nuclear program.

July/August 2025

For years, U.S. policy aimed at preventing Iran from producing a nuclear weapon has zig-zagged between threats of force, sanctions, diplomacy, and now the use of force. In 2015, President Barack Obama concluded a deal that put strict controls on Iran’s activities, called the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. But his successor, Donald Trump, abandoned the agreement in 2018, promising a better one, which never materialized. Since returning to the White House in January, Trump reimposed his “maximum pressure” campaign of sanctions on Iran, dabbled in slow-going indirect negotiations with Iran conducted through the government of Oman, then switched course in June by joining Israel in launching military strikes that pummeled Iranian nuclear facilities. U.S. and Israeli officials have provided no evidence of Iran’s weaponization. As the region’s tectonic plates shift, what happens next depends on choices made by Israel, whose power is rising, and Iran, whose power is weakening, as well as the roles played by the United States and other key countries. Carol Giacomo, editor of Arms Control Today, interviewed former U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman, the chief U.S. negotiator for the 2015 nuclear deal when she was undersecretary of state for political affairs, for her insights.

Arms Control Today: The Iranians said July 2 they are halting cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), whose inspection teams have been on the ground in Iran to ensure the country is not producing nuclear weapons. How much of a problem is that?

Former U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman: I fully expected that to happen because Iran is a country based on resistance and thus had to say to the world, “now that you’ve bombed us, we make our own decisions. We’re not going to allow people to have eyes on what we do,” even knowing that there are other ways for people to have eyes on what they do, even if less comprehensive. Negotiations matter a great deal now to get the IAEA back into Iran. That is crucial because otherwise, we will have less knowledge about what’s happening in Iran. You cannot bomb away knowledge. I fully expect that some, if not all, of the 400 kilograms of enriched uranium at 60 percent and some centrifuges—probably advanced centrifuges—have been hidden away somewhere, maybe in the bowels of Isfahan; the deep underground at Isfahan was not bombed. Or it is possible that there is an unknown site.

My added worry now is that the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and the Quds Force and other “hard hardliners” will decide that they have to go for a nuclear weapon because they see it as the only real deterrent. And if Iran decides to go for a nuclear weapon, Saudi Arabia will decide it needs a nuclear weapon. South Korea will argue it should be able to have a nuclear weapon. Japan may argue it needs a nuclear weapon. Other countries may as well, and then we are in a terrible place.

The nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) has done a pretty good job of keeping the number of nuclear weapons states small and it is crucial for that to continue to be the case. So, I hope the [U.S. President Donald Trump] administration does engage in negotiations with Iran. It doesn’t surprise me that Iran booted the IAEA. It doesn’t surprise me that they’re not ready to negotiate as we speak. But [Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas] Araghchi said the other day, “our door is never closed to negotiations.” So, to me, that’s a signal it can happen. The Trump administration just has to decide it wants to do the very hard work of diplomacy. So far, that has not been the case. That’s been clear with Ukraine, that’s been clear with Gaza, and that’s been clear with Iran. That’s been clear in their tariff deals. There are no “90 deals in 90 days,” no Iran deal in 60 days, no deal in two weeks with [Russian President Vladimir] Putin. It’s ridiculous. Diplomacy takes time, hard work.

ACT: Does the Trump administration have a strategy for dealing with Iran?

Sherman: As this interview goes to press, Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu is meeting with President Trump, members of the cabinet, and with members of Congress. Steve Witkoff [the U.S. special envoy] is ostensibly slated to travel to Doha yet this week to help try to finalize a Gaza ceasefire and return of hostages. Trump has said a deal could happen this week and although we all hope for that, we have been here before. Even as the administration says the deal is 80-90 percent there, the last percentage points are always the hardest.

Looking at a broader view, rumors and suggestions have been circulated by the administration that combine a broadening of the Abraham Accords; an Arab coalition to support Gaza during reconstruction and reform of the Palestinian Authority; along with recognition of Syria; a new Lebanon; and clearly a diminished Hezbollah, Hamas, and an Iran that must rebuild and negotiate. We will see this week if there remains significant daylight between Trump and Netanyahu on all of these possibilities along with the necessity for a political horizon for Palestinians to ensure a future for Palestinians as well as long-term security for Israel.

ACT: Iran has said it needs assurances that its nuclear scientists, nuclear sites, and nuclear program will be secure and that the international community will acknowledge its right to enrich uranium. Do you think Iran could ever be confident that Israel or the United States would not bomb it again?

Sherman: It would be very hard for Iran to have that kind of confidence, given what occurred. However, they also know that Trump does make deals. And this is about making a deal, not withdrawing from a deal. Maybe the Iranians can be convinced that if Trump makes a deal with them, that in and of itself gives them some security that the deal will last. So, that’s possible. It’s sort of the counterintuitive argument, when someone is the kind of leader that Donald Trump is. However, Trump has called for complete dismantlement of the nuclear program and Iran has always insisted that it has the right to enrich for civil, peaceful purposes.

ACT: Do you think the Europeans who were part of the 2015 nuclear deal—France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, or EU3—are going to reimpose the UN snapback sanctions that were part of the deal? Should they?

Sherman: I don’t know. Now that the IAEA has, in essence, been kicked out of Iran, it puts the EU3 in a much tougher position, increasing the chances of snapback. Now, you know that it’s a process that has to start before the end of October, so I think the next period of time matters tremendously in terms of the trajectory with Iran. If the Trump administration can engage in actual negotiations, if the Europeans do, if the relationship between Iran and Saudi Arabia deepens in any way, which I would be surprised about, whether any negotiations could get the IAEA back in—I mean, if there’s progress over the next couple of months, then the Europeans might hold off.

ACT: There have been a lot of mixed messages about the damage that was done with those military strikes by the United States and Israel. Trump insists the Iranian program was obliterated. IAEA Director-General Rafael Mariano Grossi said a few months. The Pentagon said the program was set back by one or two years. Trump told NATO, “I don’t see Iran being back in the nuclear business anymore.” What is the effect of these mixed messages? Where do you really think things stand?

Sherman: I’m not a nuclear scientist, but the ones that I’ve spoken with think it’s months to a year. But it really depends on where that uranium stockpile is. It depends on where the centrifuges are. It depends on whether the Iranians would decide to go for, in essence, a dirty bomb as opposed to a weaponized, fully loaded bomb on a missile—a very sophisticated weapon. So, there are a lot of unknowns. I absolutely don’t question that there was severe damage done to the Iranian nuclear sites that were attacked. The Iranians have said things were badly damaged. I do not believe the program was “obliterated.” Could it be a year or two? Perhaps. Could be months, even shorter than that? It really depends on where that stockpile is, where the centrifuges are, and what they choose to do or not do. If the [Iranian] Supreme Leader [Ayatollah Ali Khamenei] still doesn’t decide to go for a nuclear weapon but wants to reinstate the program, make sure it can move forward so he still has that option, and he sees what the world is going to do, he might do that. So, I think there are a lot of unknowns.

ACT: When you and others talk about assessing the damage, though, doesn’t it depend on exactly what you’re talking about? Does it mean, has it set back achieving the maximum amount of enriched uranium that you need? Does it mean the converting enriched uranium to the metalized version?

Sherman: Right, and do you have the launch vehicle if you want to go for the real package? So yes, it very much depends on what part of this process is being discussed. But the fact is, the Iranians have mastered the entire nuclear fuel cycle. Recreating that is not hard for them. Yes, it does appear that in terms of the metallurgy conversion facility, that was really hit hard, but that doesn’t mean the Iranians can’t make a nuclear weapon. They still can.

ACT: Do you really think Trump wants negotiations or do you think he is convinced that the United States and Israel hit Iran so hard that it will now be quiescent?

Sherman: I can’t imagine his mind. But I think he’d like to tie that bow and reach a deal so he can say, “I went to do what needed to be done and it’s done.” I think he wants to focus on doing the Gaza Abraham Accord deal and tying that bow. I think it is appalling that the Trump administration has not let the weapons go forward to Ukraine and has posed no new sanctions on Russia, although this week the president appears to be allowing weapons to go forward; whether he will sustain support remains to be seen. Trump has been totally played by Putin. I also think it’s extraordinary how little contact there has been with China; he’s talked to [President] Xi [Jinping] once. But no real diplomacy appears to be going on with Beijing beyond some lower-level trade talks. The president appears to be using tariffs with Asian countries to try to constrain China’s relationship with those countries. Instead, it appears we are alienating our allies.

ACT: You said that maybe Iran would trust a deal with the United States again because it would be Trump making the deal this time and his Republican Party controls Congress. But is there something concrete that the administration is going to have do for Iran to show its bona fides, given that it was Trump who abandoned the nuclear deal in 2018?

Sherman: No, the biggest problem remains what has always been the problem and the only reason [former President Barack] Obama could get a deal. And that is, Iran believes that the NPT gives a country the right to enrich uranium for a civil nuclear program. Most of our European colleagues also believe the NPT gives a country that right. The United States has never, and still does not believe, that a country has the right. What Obama did, and how he opened the door to a deal, was to say he would consider permitting Iran to have a small civil nuclear program to enrich uranium under intrusive monitoring and verification.

Trump, because of pressure from Republican senators, the prime minister of Israel, and from a lot of his donors, has said there must be a complete dismantlement of the program. That is why Trump said he obliterated the Iranian nuclear program with the recent airstrikes because no other standard is consistent with what he has said. There must be a complete dismantlement of the program, so he has to say, “It’s been obliterated, I’m done with that.” Whether people will understand he still has to negotiate to make sure we have eyes on what’s happening in Iran, I don’t know.

ACT: What do you think the end result would have to be, or could be? Total disarmament or containment?

Sherman: I would be very surprised if Iran would agree to a total dismantlement. My understanding is the Trump administration proposed a deal where Iran would be allowed to enrich a small amount of uranium for a period of time until a consortium was formed where the enriched fuel would be created somewhere else and be available to Iran for its civil nuclear program, and the Iranians said, “No, we have a right to enrich.”

Whether the president allowed Witkoff to also put on the table all that was available as incentives, I don’t know. Obama could never put the primary economic embargo [that the United States imposed on Iran] on the negotiating table. We could offer a carve-out for Boeing and plane parts, but we couldn’t put the whole thing on the table in part, because Iran didn’t want Americans inside of Iran and politics at the time made such an agreement impossible. Ostensibly, Iran, in talks with Witkoff, said it was open to Americans being in Iran. There are, besides the primary embargo, other potential incentives the Trump administration might be able to offer that the Obama administration couldn’t because the House and the Senate belong to Trump.

ACT: You, along with other U.S. officials, spent a lot of time negotiating the 2015 nuclear deal, Trump tore it up and 10 years later, the United States and Israel end up bombing Iran—the outcome you tried to prevent. How does that make you feel?

Sherman: Few things are done-done in life. When I talk about this, I say to students, World War I was called “the war to end all wars.” Twenty years later, which is not much time in history, we had World War II. Permanent solutions are rare, if ever. So, we have to persist, we have to persist!

With no serious bilateral escalation control mechanisms on the horizon, the United States and other third parties will remain critical to South Asian crisis stability.

July/August 2025

By Moeed W. Yusuf

On April 22, 2025, a terrorist attack ripped through the town of Pahalgam in the disputed territory of Kashmir, killing 26 people. Minutes later, a crisis between nuclear rivals India and Pakistan was in the making as the Indian media began pointing fingers at Pakistan. A war frenzy built in India in the following days, with the government announcing multiple punitive steps against Islamabad, including unilaterally putting into abeyance the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty that protects the overwhelming majority of Pakistan’s water supply.1 Pakistan responded with its own diplomatic measures, downgrading the already fractured relationship further.

By the time the crisis ended nearly three weeks later, the region had witnessed the most expansive use of military force and technology since India’s and Pakistan’s nuclearization in 1998. India initiated hostilities in the early hours of May 7 by launching multiple missile and artillery strikes deep inside Pakistan. Pakistan responded, leading to an aerial engagement and the downing of multiple Indian jets. The next 48 hours featured massive drone operations and the use of air defenses to neutralize the drones by both sides. The night of May 9 and morning of May 10 produced swift escalation. India targeted multiple Pakistani air bases with cruise missiles, including a critical air base situated in the city of Rawalpindi, just minutes from where Pakistan’s military chain of command is headquartered. Pakistan retatliated by using short-range ballistic missiles against Indian military infrastructure.

The spread and scale of the military attacks and use of new technologies by both rivals was unprecedented.2 The choice of targets, especially by India, was also highly escalatory. Before U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced an abrupt end to the crisis May 10, both countries had entered uncharted territory, seemingly committed to continuing military operations to deny the other escalation dominance, if not to establish their own. South Asia truly seemed at the brink of a major war.

This article examines the Pahalgam crisis through the lens of brokered bargaining, a crisis-management framework that centers on the role of the United States and other third parties in determining crisis behavior and the risk of escalation.

Brokered Bargaining in India-Pakistan Crises

Originally presented in my 2018 book, Brokering Peace in Nuclear Environments: U.S. Crisis Management in South Asia, the term “brokered bargaining” reconceptualizes nuclear crisis behavior by positioning it within a three-way bargaining framework involving two regional nuclear rivals and powerful third-party brokers.3 At its core lies the notion that during crisis moments between regional nuclear powers, the third party plays a pivotal role in brokering de-escalation, not merely as a passive observer, but as an active, strategic intermediary navigating between both sides’ red lines. Regional antagonists attempt to compel or deter each other, but also seek to influence the third party, often deferring to its cues even as the rivals attempt to exhibit some strategic autonomy in decision making to manipulate the risk of war and extract maximum concessions from the brokers. Ultimately, the innate risk of nuclear war ensures that the third party’s overriding interest—ahead of its broader geopolitical equities—remains swift de-escalation and termination of the crisis.

Brokered bargaining has featured prominently in each of their conflicts. India, Pakistan, the United States, and other important countries have internalized the triangular dynamic in their crisis strategies over the past quarter century. Starting with the 1999 Kargil war, the first decade of nuclear crisis management in South Asia saw the United States, supported by other third parties, proactively intervening early on. They looked for the quickest way to de-escalate tensions, even momentarily overshadowing their larger foreign policy equities.

As India-U.S. relations grew into a strategic partnership, the U.S. propensity to play down the middle with an almost singular focus on de-escalation loosened somewhat. After a mini crisis in 2016 and a more significant one three years later, an initial U.S. response heavily tilted in India’s favor emboldened New Delhi to use limited military force. Although this made crisis management more complex, especially in the Pulwama crisis in 2019, when India and Pakistan ended up in an aerial dogfight, the United States and other third parties’ willingness to broker de-escalation was never in doubt in either case.4

The timing of the tensions over the Pahalgam attack was extremely concerning from the perspective of South Asian crisis management. The conflict occurred against the backdrop of a massive shift in U.S. global posture. President Donald Trump’s plans to pull back the United States from its role as the global sheriff raised serious concerns about the willingness of the principal broker to engage in a crisis far away from home. This added to the region’s crisis-management conundrum, already challenged due to the absence of robust bilateral escalation-control mechanisms between India and Pakistan. The two countries do not have meaningful arms control treaties or escalation control protocols and have failed to use their communication hotlines dependably in past crises.

Would the brokered bargaining framework—which is assumed to have permanence across time and space in the absence of dependable bilateral crisis management—hold, or would Washington leave New Delhi and Islamabad to themselves to pull back from the brink? As the two sides entered the Pahalgam crisis, the answer to this question was central to how the situation would play out.

The Pahalgam Crisis

India and Pakistan started the crisis in a familiar pattern, assuming the centrality of the third party and its eager availability as broker. Immediately after militants struck in Pahalgam April 22, India began playing on the Western world’s propensity to associate Pakistan with terrorism by blaming the attack on an alleged offshoot of a Pakistan-based terrorist outfit. As with the Pulwama crisis, India promised a tough response, with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi vowing to punish “every terrorist and their backers.”5 Also consistent with previous crises, Pakistan called for an investigation into the attack and signaled its preference for calm, while simultaneously emphasizing that it will respond in kind to any Indian use of force. Pakistani officials pointedly reminded the world of the nuclear context and “the prospect of a full-scale military conflict in the region” should India flex its military muscle.6

These signals of resolve from both sides are meant to put third parties on notice to prevent major war, and they drew a swift global response, featuring a third-party script that was virtually identical to previous crises. Shortly after the attack, sympathies and messages of international support poured in for India. Trump posted: “Prime Minister Modi, and the incredible people of India, have our full support and deepest sympathies.”7 Some capitals went further, hinting at support for India’s need to react to the terrorist incident. Russian President Vladimir Putin stated: “This brutal crime has no justification whatsoever. We expect that its organizers and perpetrators will face a deserved punishment.”8 April 25, amid war frenzy in the Indian media, the Indian defense minister claimed that U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth had “supported India’s right to defend itself” during their phone conversation.9 The United States had conveyed an identical message six years earlier during the Pulwama crisis.

In light of these messages, Indian leaders reasonably could have perceived the situation to be analogous to the days after the onset of the Pulwama crisis. At the time, they had concluded that they had international backing to use force against Pakistan and executed an airstrike across the international border.

Temporarily Going Off-Script

Then came the twist—unprecedented and with uncertain implications. Amid intensifying war rhetoric from both sides, Trump hinted April 26 that his broad vision of an inward-looking United States applied to nuclear crisis management in South Asia. Asked whether he was willing to engage in de-escalating tensions, he said: “I am very close to India and I’m very close to Pakistan, as you know.… I am sure they’ll figure it out one way or the other. I know both leaders.”10

Trump’s message could have been read in different ways. India could have felt further emboldened that the United States would stand by if it used force against Pakistan. Pakistan, for its part, may have taken heart from the fact that Trump had equated his outlook toward the two rivals. More significantly, the U.S. president’s statement would have caused alarm in other third-party capitals, such as Riyadh, London, Abu Dhabi, Berlin, Beijing, and Moscow, who generally follow the U.S. lead in these situations, because it implied that the principal crisis broker, despite the advantage of having the institutional memory of leading crisis diplomacy in South Asia, may in fact be opting for strategic detachment. Regional and global capitals seemed to have taken note. What followed was a flurry of signaling and diplomacy by other third parties as they sought to fill the U.S. vacuum. Their message was restraint, which was even more important now given that none of them had ever tested their crisis influence over India and Pakistan without the United States in the lead.

On April 28, the Russian Foreign Ministry issued an “appeal to both sides for restraint and constructive dialogue.”11 China joined in, asking for restraint while backing Pakistan’s calls for an investigation into the Pahalgam attack. Iran, whose role had been muted in previous crises, offered to mediate. Its foreign minister visited Islamabad and New Delhi to help calm tensions. Saudi Arabia also activated its mediatory role and conducted shuttle diplomacy as the situation escalated into actual combat.

India continued to maintain a resolute stance. Modi announced April 29 that he had given “complete operational freedom” to the Indian military to choose the “mode, targets, and timing” of military action against Pakistan.12 Indian External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar communicated India’s determination to Rubio May 1, warning that the Pahalgam attack’s “perpetrators, backers and planners must be brought to justice.”13 Jaishankar gave a similar message to his Russian counterpart a day later.

India’s initiation of hostilities May 7 confirmed that its leaders felt they had enough diplomatic cushion to flex their muscle despite attempts by regional third parties to dissuade them from doing so. Washington’s seeming detachment would not have gone unnoticed in New Delhi. Even after the initial night of missile launches inside Pakistan, U.S. Vice President JD Vance stated: “we’re not going to get involved in the middle of war that’s fundamentally none of our business.”14 Although this initially worked to India’s advantage, the elephant in the room was obvious to all, including India: how to de-escalate the crisis without the United States brokering an exit?

A Return to Familiar Ways

The following 48 hours would answer this question unequivocally. Amid swiftly escalating tit-for-tat military action and no obvious off-ramps, the most fundamental premise of brokered bargaining kicked in: the possibility that nuclear war, no matter how low, forces the principal third party to seek immediate crisis de-escalation above all else, and the regional rivals find this risk factor too costly to ignore. From this point on, the crisis plays out as competition between the rivals to extract maximum gains from the third party while agreeing to terminate hostilities.

By May 9, the Trump administration had determined that the “conflict was at risk of spiraling out of control” and that crisis diplomacy by regional actors was proving insufficient.15 Uncertainty over the U.S. commitment to play broker disappeared. Vance and Rubio worked the phones intensely to seek an immediate ceasefire. Other capitals quickly put their weight behind this welcome effort, impressing upon India and Pakistan the need to terminate the crisis. The Group of 7 states issued a rare joint statement urging “immediate de-escalation.”16 Virtually all other countries, including China, called for calm, as well.

Rubio succeeded in convincing both sides to agree to a ceasefire without waiting to work out its specific contours. He informed his Pakistani and Indian counterparts that their rival was willing to terminate the crisis if they would desist from further military action.17 Predictably, Washington’s messaging to New Delhi and Islamabad highlighted the risks of a broader conflagration while presenting inducements. Pakistan, for instance, was offered “U.S. assistance in starting constructive talks in order to avoid future conflicts.”18

Once the United States assumed the lead, Indian and Pakistani sensitivity to third-party preferences was obvious given their abrupt decision to end hostilities. This is especially true in India’s case because it did not feel its crisis objectives had been met. Subsequent statements by Indian leaders left no doubt that India had left the crisis dissatisfied. Pakistan also quickly dialed down tensions once the United States made its intent clear. Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif cancelled a National Command Authority meeting he had called,19 this being the only move from either side during the crisis that could ostensibly be considered a nuclear signal.

In the early afternoon of May 10 in South Asia, Rubio made the U.S. success public in a social media post: “Over the past 48 hours, @VPVance and I have engaged with senior Indian and Pakistani officials… I am pleased to announce the Governments of India and Pakistan have agreed to an immediate ceasefire and to start talks on a broad set of issues at a neutral site.”20 Trump later boasted: “We stopped a nuclear conflict. I think it could have been a bad nuclear war … so, I’m very proud of that. I said to India and Pakistan: Let’s stop it. If you stop it, we’ll do trade. If you don’t stop it, we’re not gonna do any trade … and all of a sudden, they said, ‘I think we’re gonna stop.’”21

It remains unclear what triggered the sudden U.S. decision to reclaim its role as the principal broker in India-Pakistan crises. One account suggests that New Delhi approached Washington and other capitals, seeking their intervention in the face of Islamabad’s unexpected military response to India’s targeting of Pakistan’s air bases.22 The New York Times, on the other hand, reported that the United States intervened due to its fear that rapid escalation might be turned into a nuclear exchange. According to this report, “what drove Mr. Vance and Mr. Rubio into action was evidence that the Pakistani and Indian air forces had begun to engage in serious dogfights, and that Pakistan had sent 300 to 400 drones into Indian territory to probe its air defenses. But the most significant causes for concern came late Friday [May 9], when explosions hit the Nur Khan air base in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, the garrison city adjacent to Islamabad.”23 At the time, there was also chatter in Indian media—later proven to be false—of possible leakage of nuclear radiation caused by one of the Indian strikes.24

The Future of Crisis Management in South Asia

The Pahalgam crisis followed the disturbing trend where each new South Asian conflict has become more complicated and more expansive in the use of military force than the previous one. Ultimately, it also exhibited the enduring logic of brokered bargaining that has thus far prevented a major regional catastrophe.

Nevertheless, South Asia remains on edge. Although both militaries have pulled back their forces to honor the ceasefire, Modi has declared that the ceasefire is “only paused.”25 India also has declared a “new normal,” claiming that it will be justified in waging war against Pakistan in response to any future terrorist attack. The potential triggers for a future crisis have expanded in other ways, too. For instance, Pakistan formally has declared that any Indian attempt to follow through on its threat to divert Pakistan’s waters under the Indus Water Treaty will be seen as an “act of war.”26

Moreover, with the introduction of new technologies, whose use unnerved both sides in the recent fighting, crisis trajectories would become even more complex. Drone warfare and stand-off missile strikes will compress the time for decision-making and allow the combatants to test thresholds without immediately risking escalation. The expansive list of targeting and counter responses that dramatically escalated the Pahalgam conflict are not likely to be rolled back.

With no serious bilateral escalation control mechanisms on the horizon, the United States and other third parties will remain critical to South Asian crisis stability because of the structural imperatives of nuclear risk and the psychological need for face-saving exits for the two rivals when tensions rise. The United States must remain on guard, shedding any uncertainty about its willingness to play broker in coordination with other important states.

That said, it should be clear that third party-led crisis management is not a recipe for sustained peace and stability. No matter how effective, brokered bargaining will remain full of risks and challenges associated with the involvement of multiple actors in a fast-moving crisis environment. Sustainable peace in South Asia is only possible by ensuring that crises are prevented from occurring in the first place. This requires the world to push for a serious Indian-Pakistani dialogue that seeks to address the adversaries’ outstanding disputes and contentious issues—the very root cause of bilateral tensions. Trump would do well to follow up on his promise to facilitate this conversation in the interest of regional peace and stability. Failing that, South Asia will remain on the brink.

ENDNOTES

1. Aishwaria Sonavane, “After Pahalgam, India Faces Tough Security and Diplomatic Choices,” The Diplomat, April 28, 2025.

2. Christopher Clary, “Four Days in May: The India-Pakistan Crisis of 2025,” Stimson Center, May 28, 2025.

3. Moeed W. Yusuf, Brokering Peace in Nuclear Environments: U.S. Crisis Management in South Asia (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018).

4. Moeed W. Yusuf, “The Pulwama Crisis: Flirting with War in a Nuclear Environment,” Arms Control Today, May 2019.

5. “India will Pursue Kashmir Attackers to the Ends of the Earth, says PM Modi,” BBC News, April 24, 2025.

6. “Defence Minister Khawaja Asif Warns of ‘All-out War’ if India attacks,” Dawn, April 24, 2025.

7. Donald J. Trump post on Truth Social, April 22, 2025.

8. “Trump, Putin, Meloni and Other World Leaders condemn Pahalgam Terror Attack,”

The Hindu, April 23, 2025.

9. “US Backs India’s Right to Defend Itself: Hegseth,” Times of India, May 2, 2025.

10. “US President Trump Confident Pakistan, India will ‘Figure Out’ Border Tensions,” Dawn, April 25, 2025.

11. “Russia Urges Pakistan, India to Exercise Restraint, Engage in Dialogue — MFA,” TASS News Agency, April 28, 2025.

12. “India Gives Army ‘Operational Freedom’ to Respond to Kashmir Attack,” France 24, April 29, 2025.

13. Indian External Affairs Minister Dr. S. Jaishankar on X (@DrSJaishankar), “Discussed the Pahalgam terrorist attack with US @SecRubio yesterday. Its perpetrators, backers and planners must be brought to justice,” May 1, 2025.

14. Morgan Phillips, “Vance Says India-Pakistan Conflict ‘None of Our Business’ as Trump Offers US help,” Fox News, May 9, 2025.

15. David Sanger, Julian Barnes, and Maggie Haberman, “Reluctant at First, Trump Officials Intervened in South Asia as Nuclear Fears Grew,” The New York Times, May 10, 2025.

16. “G7 Countries Call for ‘Immediate De-escalation’ in India-Pakistan Conflict,” The Hindu, May 10, 2025.

17. Nic Robertson and Sophia Saifi, “‘We Hope Sense will Prevail,’ Pakistan’s Foreign Minister Says as Delicate India-Pakistan Ceasefire Holds,” CNN, May 13, 2025.

18. “Secretary Rubio’s Call with Pakistani Army Chief Asim Munir,” Readout, Office of the Spokesperson, U.S. Department of State, May 9, 2025.

19. “No Meeting of National Command Authority Scheduled: Defence Minister,” Business Recorder, May 10, 2025; Clary, “Four Days in May.”

20. U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio on X (@SecRubio), “Over the past 48 hours, @VP Vance and I have engaged with senior Indian and Pakistani officials,” May 10, 2025.

21. Anwar Iqbal, “Trump Says US Stopped Pak-India ‘Nuclear War,’” Dawn, May 13, 2025.

22. Middle East Eye on X (@MiddleEastEye), “In a CNN report, correspondent Nick Robertson stated that India reportedly sought assistance from the US, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey to help de-escalate the conflict,” May 11, 2025.

23. Sanger, Barnes, and Haberman, “Reluctant at First.”

24. “No Radiation Leak from any Nuclear Facility in Pakistan: IAEA,” The Hindu, May 15, 2025.

25. “India’s Modi Says Fighting ‘Only Paused’ in Wake of Conflict with Pakistan,” Al Jazeera, May 12, 2025.

26. Pakistani Prime Minister’s Office, “Prime Minister Muhammad Shehbaz Sharif Chaired a Meeting of the National Security Committee (NSC), Today,” Press Release, Prime Minister’s Office, April 24, 2025.

Moeed W. Yusuf is the president of Beaconhouse National University in Pakistan, a senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center, and the author of Brokered Bargaining in Nuclear Environments: U.S. Crisis Management in South Asia. He served as the national security adviser/special assistant to the prime minister of Pakistan from 2019 to 2022.

U.S. President Donald Trump claims that Israeli and U.S. strikes “obliterated” Iran’s nuclear program but other experts were more cautious.

July/August 2025

By Kelsey Davenport

U.S. President Donald Trump claimed that Israeli and U.S. strikes against Iranian nuclear facilities obliterated the program, but early intelligence assessments and the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) suggest that the program may only have been set back a matter of months.

Neither the United States nor Israel presented intelligence suggesting that Iran had decided to weaponize its nuclear program, but the strikes are prompting debate in Iran about the value of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and negotiations with the United States.

Trump announced that the United States conducted a “very successful attack” on three Iranian nuclear sites in a June 21 Truth Social post. For the first time, the United States used the largest bomb in its conventional arsenal, the massive ordinance penetrator, to target the deeply buried Fordow uranium enrichment facility. Tomahawk cruise missiles were deployed against the Natanz uranium enrichment facility and the Esfahan complex, where Iran conducted uranium conversion activities and stored at least some of its highly enriched uranium.

All three sites were part of Iran’s declared nuclear program and under IAEA safeguards. The agency’s director-general, Rafael Mariano Grossi, said in a June 17 CNN interview that the IAEA “did not have proof of a systemic effort [by Iran] to move into a nuclear weapon.” Grossi condemned the strikes and told the UN Security Council June 20 that “armed attacks on nuclear facilities should never take place.”

The U.S. strikes followed a week of Israeli strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities that began June 13. Israel’s initial targets included Natanz and the assassination of more than a dozen top Iranian nuclear scientists. Israel also targeted key Iranian military leaders and ballistic missile launch sites. In the following days, Israel damaged several buildings at Esfahan and an unfinished reactor at the Arak site.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did not present any intelligence suggesting that Iran’s nuclear program posed an imminent threat. He said June 13 that the strikes were intended to “eliminate” Iran’s nuclear and missile program.

Israel, however, does not have the military capabilities to target Iran’s deeply buried and hardened nuclear facilities. Netanyahu’s determination to “eliminate” the program, despite lacking the conventional capabilities to do so, suggests that he sought to pull the United States into the conflict to target the facilities beyond Israel’s reach.

Hours after the June 13 strikes, Iran responded with counterstrikes targeting Israel. Israel, with U.S. assistance, intercepted the majority of the incoming missiles and drones, but over the course of the 12-day conflict, some missiles did make it through Israel’s defenses.

Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, claimed victory, saying in a June 24 address that Iran struck a “large number of [Israeli] military” targets and critical infrastructure. He downplayed the attacks on Iran’s nuclear facilities, saying the strikes could not achieve “anything significant.”

Iran and Israel accused each other of deliberately targeting civilian areas during the 12-day conflict.

Following the U.S. attack, Iran launched ballistic missiles at the U.S. Al-Udeid Air Base in Qatar. Trump said that Iran warned the United States ahead of the June 23 attack, mitigating the damage caused by the strike. The advance warning suggested that Iran sought to prevent further escalation with the United States.

Following the counterstrike, Trump announced a ceasefire and called for peace.

Although the U.S. and Israeli strikes damaged key Iranian nuclear facilities, it is unclear how much the military action set back Iran’s nuclear program.

Following the U.S. strikes on Fordow, Natanz, and Esfahan, the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency assessed in a classified report that the strikes only set back Iran’s nuclear program by “maybe a few months,” an official familiar with the report told CNN. Unnamed officials quoted by CNN said that Iran’s stockpile of enriched uranium was not destroyed by the strikes and that Iran’s centrifuges are largely intact.

U.S. officials, including Trump, rejected the assessment. Trump insisted repeatedly, including in a June 29 interview on Fox News, that the strikes “obliterated” Iran’s nuclear program. U.S. Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard said Iran’s nuclear facilities were “destroyed” and it would take “years” for Iran to rebuild Natanz, Fordow, and Esfahan. In a June 25 statement, the Israel Atomic Energy Commission offered a similar assessment, saying that the combined strikes set back Iran’s ability to build nuclear weapons “by many years.” On July 2, the Pentagon put the estimate at “one to two years.”

Grossi, however, assessed that Iran could resume uranium enrichment in a “matter of months.” In a June 29 interview with CBS, he said that although Iran’s facilities were “severely damaged,” the country has the “industrial and technological capabilities” to rebuild.

Grossi also raised concerns about the whereabouts of Iran’s enriched uranium, which Tehran had threatened to move from its declared sites in the event of an attack. Following the Israeli strikes, Iran informed the IAEA that it would take “special measures” to protect its nuclear materials.

U.S. Vice President JD Vance admitted in a June 23 interview on Fox News that the United States does not know if the strikes destroyed Iran’s stockpile of uranium enriched to near-weapons-grade levels.

Iran was enriching uranium to near-weapons-grade levels before the Israeli strike. According to a May 31 IAEA report, Iran had produced more than 400 kilograms of uranium enriched to 60 percent uranium-235. That stockpile, if enriched to the 90 percent U-235 that is considered weapons-grade, would be enough for about 10 bombs.

Vance said the goal was to “bury” the material and ensure Iran cannot enrich it further. According to a CNN report, Gen. Dan Caine, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told senators in a June 26 classified briefing that the United States does not have the military capability to destroy the deeply buried facilities at Esfahan, where Iran may have been storing that material. The U.S. Tomahawk strike on Esfahan may have been designed to collapse the entrances to the facility. Grossi said in a June 22 statement that the attack “impacted” the entrances to the underground tunnels at the site.

But Marco Rubio, the U.S. secretary of state and interim national security advisor, suggested that the whereabouts of Iran’s near-weapons-grade uranium is immaterial, given the destruction of Iran’s uranium metal production facility at Esfahan. Iran would need to convert uranium from gas to the metal form necessary to build a bomb. Iran “can’t do a nuclear weapon without a conversion facility,” Rubio told CBS News

on June 22.

Grossi called for the return of IAEA inspectors to Iran’s nuclear facilities and begin trying to account for nuclear materials, but Amir Iravani, Iran’s ambassador to the UN, said the agency “cannot have access” to Iran’s nuclear sites.

Esmaeil Baghaei, Iran’s foreign ministry spokesman, said in a June 16 press briefing that the parliament drafted legislation calling for the country to withdraw from the NPT. The parliament chose instead to pass a law June 18 prohibiting cooperation with the IAEA. Iran, as an NPT state-party, is legally required to implement a safeguards agreement with the IAEA. The new law, however, requires that before resuming cooperation with the agency, Iran must receive assurances that its nuclear facilities and scientists will be secured and that its NPT rights, including the right to enrichment, will be respected. The law entered into effect July 1.

The NPT guarantees that non-nuclear-weapon states can access nuclear technology for peaceful purposes under IAEA safeguards but does not explicitly mention a right to uranium enrichment.

Grossi said the implications of the Iranian law on the agency’s ability to conduct safeguards is unclear, but he emphasized the importance of the IAEA returning to Iran’s nuclear facilities and conducting inspections.

Araghchi said in a June 26 interview with Tasmin that Iran has “no plans” to invite Grossi to Tehran. Iranian President Massoud Pezeshkian told French President Emmanuel Macron in a June 30 call that Iran’s trust in the agency is broken, primarily because the agency did not condemn the United States and Israel for attacking Iranian sites.

Macron said in a June 23 press conference in Oslo that France shares the goal of preventing Iran from developing nuclear weapons but that “there is no legality” in the U.S. strikes on Iran.

In addition to the technical challenges posed by the prohibition on the IAEA, there are political challenges to resuming negotiations.

Israel struck Iran shortly before Iranian and U.S. negotiators were set to meet for a sixth round of talks on a new nuclear deal, leading some Iranian policymakers to accuse the United States of not negotiating in good faith.

In his June 26 interview, Araghchi said that the United States “betrayed diplomacy mid-negotiation” and the experience will influence Iran’s decision about future talks. He said the strikes make reaching an agreement “far more complex and complicated.”

Since the June 21 strikes, the Trump administration has sent mixed messages about its interest in returning to negotiations. After suggesting June 25 that talks would resume the following week, Trump said that the United States and Iran “may sign an agreement,” but he does not “think that it’s necessary.”

In a June 25 interview with CNBC Steve Witkoff, Trump’s envoy to the Middle East, suggested, however, that the United States will continue to push for a deal.

He said that “enrichment is the redline” and that Iran should pursue a nuclear program similar to that of the United Arab Emirates, which signed a nuclear cooperation agreement with the United States in which it voluntarily gave up uranium enrichment and plutonium reprocessing.

Iranian President Massoud Pezeshkian said in a July 7 interview with Tucker Carlson that a deal with the United States is possible, but that Iran's nuclear rights must be respected. He also questioned how Iran can trust Trump to negotiate in good faith after the military strikes. Trump has suggested that Iran would more likely accept U.S. terms for a deal after the military strikes.

New programs and accelerated funding would increase Pentagon spending on nuclear forces to $62 billion in the Trump administration’s 2026 defense budget request.

July/August 2025

By Xiaodon Liang

New programs and accelerated funding would sharply raise Pentagon spending on nuclear forces to $62 billion under the Trump administration’s fiscal year 2026 defense budget request.

Detailed justification of the request, published June 26, arrived after months of complaints from lawmakers about administration delays, and without information typically provided by the armed services on cost projections for future years.

The president’s proposal includes spending $4.1 billion in research and development funding for the behind-schedule Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) program, $10.3 billion across R&D and procurement accounts for the B-21 stealth bomber, and $11.2 billion in R&D and procurement for Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines.

The nuclear-capable sea-launched cruise missile program, proposed by the first Trump administration in 2018 but opposed by former President Joe Biden, would add $1.9 billion in R&D funding to the modernization program in fiscal 2026, according to the request.

With proposed spending on Department of Energy nuclear weapons programs reaching $25 billion in this year’s budget request, nuclear forces would cost a total of $87 billion in fiscal 2026 under the White House plan. That would represent a 26-percent increase over the Biden administration’s last budget request, and the second year in a row in which total nuclear costs have increased by more than 20 percent. (See ACT, April 2024.)

Speaking June 12 as an impatient House Appropriations Committee voted on its defense budget bill even before the administration released its full request, Rep. Ken Calvert (R-Calif.), chairman of the defense subcommittee, noted that the absence of line-item and justification documents meant “the committee was unable to examine up-to-date program execution data and found it more difficult to assess either opportunities for increased investment or for additional reductions and eliminations.”

Under the president’s defense spending plan, substantial portions of the Sentinel ICBM and the B-21 bomber allocations—and all the sea-launched cruise-missile funding—will be paid for through a supplementary budget reconciliation bill. The final version of that bill adds an additional $1.7 billion for nuclear weapons programs compared to the House text passed in May. (See ACT, June 2025.)

The president’s proposed $4.1 billion in total Sentinel funding in fiscal 2026 would represent a marked increase over the money spent last year. After Congress cut the new ICBM’s budget to $3.2 billion for fiscal 2025, down from an initial request of $3.7 billion, the Pentagon shifted a further $1.2 billion to other programs as the Air Force continued to reassess its plans for the missile following a Nunn-McCurdy cost overrun review. (See ACT, September 2024.)

“An adjustment of this magnitude should have been accompanied by proactive communications including robust details on a rephasing plan,” House appropriators chided the Air Force in their bill report.

Gen. Thomas A. Bussiere, commander of U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command, said June 16 in an interview with Defense Daily that he approved several weeks ago modified plans for the overhaul of existing silos or construction of new silos for two of three ICBM missile wings. The Air Force believes the Sentinel program will depend “predominantly” on new silos for the ICBM program, the service told Breaking Defense in early May.

The Sentinel missile itself may not be tested in flight for the first time until March 2028, two years behind schedule, the Government Accountability Office said in its annual weapons acquisition report.

The $10.3 billion budget for the B-21 bomber would represent a sharp rise over the $5.3 billion in R&D and procurement funding enacted by Congress in both fiscal 2024 and 2025. It is also a jump when compared with the $6.0 billion that the Air Force indicated last year that it likely would ask for in fiscal 2026.

The funding increase is in line with an acceleration of bomber production previewed by the Air Force in hearings earlier this year. (See ACT, May 2025.)

The cost of the Columbia-class program will increase from $9.8 billion to $11.2 billion under Navy plans. Navy officials told the Senate Appropriations Committee’s defense subcommittee June 24 that the lead boat is now two years behind schedule and will not be completed until March 2029.

The Pentagon intends to spend $25 billion on Golden Dome programs to acquire and integrate new and existing missile defense systems. The Missile Defense Agency (MDA) requested large increases to R&D programs for command and control and battle management, ground-based missile defense sensors, and the Aegis sea-based midcourse missile defense program. The agency’s overall funding would increase 27 percent, from a fiscal 2025 enacted budget of $10.4 billion to $13.2 billion in the fiscal 2026 proposal.

The Aegis program, which would see its procurement and R&D budgets increase to $2.1 billion in fiscal 2026, also will conduct “underlay design and development to deliver an Aegis Combat System and containerized SM-3 [interceptor] as part of the expanded Homeland Defense architecture,” the MDA’s budget documentation said. The program envisions using the Block IIA variant of the SM-3 interceptor, which MDA tested against an ICBM-range target in 2020.

The MDA previously proposed a homeland defense “underlayer” in its fiscal 2021 and 2022 budgets, but Congress largely defunded this effort. (See ACT, January/February 2022.)

The Space Force would receive $2.6 billion in base and reconciliation R&D funding for the missile tracking layer of its Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture in low-Earth orbit, up from $1.7 billion last year.

The budget documents also indicate that the Air Force intends to revive a boost-glide hypersonic missile program that was scrapped after a series of disappointing tests. The Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon would receive $387 million in procurement funding in fiscal 2026, after Congress initially zeroed out the program in the fiscal 2024 budget and the Air Force declined to ask for more money in fiscal 2025. (See ACT, January/February 2024.)

But the other Air Force hypersonic weapon, the scramjet Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile, would also receive a funding boost, from $467 million in fiscal 2025 to $803 million in fiscal 2026.

Meanwhile, the parallel Army-Navy programs to jointly develop a common hypersonic missile will see modest budget cuts, from $904 million to $798 million on the Navy side, and from $1.1 billion to $891 million on the Army side. The Army is already procuring its variant, known as the Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon, with eight missiles ordered last fiscal year and three planned for this year.