“For half a century, ACA has been providing the world … with advocacy, analysis, and awareness on some of the most critical topics of international peace and security, including on how to achieve our common, shared goal of a world free of nuclear weapons.”

STATEMENT: Renewed U.S. Military Attacks on Iran Not Justified on Nonproliferation Grounds, Say Nuclear Experts

Another U.S. aerial military strike on Iran, as President Trump said today he is considering, would not advance the goal of blocking Iran’s potential pathways to acquire nuclear weapons if its leaders were to decide to do so.

False Start or New Era: Trump’s Call for “Multilateral” Nuclear Talks

Nuclear Disarmament Monitor

February 2026

Following the Feb. 5 expiration of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), President Donald Trump and senior administration officials say the United States seeks multilateral talks that involve Russia as well as China as a means to make progress on nuclear arms control and risk reduction.

Is Trump Jeopardizing Nonproliferation Efforts to Get A Nuclear Cooperation Deal with Saudi Arabia? A Report To Congress Suggests He Is.

When the Trump administration announced a joint declaration on U.S. nuclear cooperation with Saudi Arabia in November 2025, the White House claimed the proposed deal would lead to a “decades-long multi-billion-dollar nuclear energy partnership” with benefits to American nuclear companies. But U.S. officials dodged key questions about the nonproliferation obligations Saudi Arabia—a country that has openly threatened to develop nuclear weapons if Iran does—will be subject to under the proposed agreement.

Volume 18, Issue 2,

February 19, 2026

When the Trump administration announced a joint declaration on U.S. nuclear cooperation with Saudi Arabia in November 2025, the White House claimed the proposed deal would lead to a “decades-long multi-billion-dollar nuclear energy partnership” with benefits to American nuclear companies. But U.S. officials dodged key questions about the nonproliferation obligations Saudi Arabia—a country that has openly threatened to develop nuclear weapons if Iran does—will be subject to under the proposed agreement.

A report the Trump administration sent to Congress weeks ago, which was recently obtained by the Arms Control Association, suggests why U.S. officials may have dodged tough questions about the deal: the proposed agreement appears to fall short of expected nonproliferation provisions that have widespread bipartisan support.

Specifically, the report suggests that, as negotiated, the nuclear cooperation agreement will open the door to some type of Saudi uranium enrichment program and will not require a more intrusive International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) monitoring arrangement, increasing the risk that Riyadh could exploit a civil nuclear program for weapons purposes in the future. This stands in contrast with what Republican and Democratic congressional leaders have consistently insisted the United States pursue in negotiations with Saudi Arabia—a “Gold Standard” agreement, which would require a commitment to forgo uranium enrichment and reprocessing and adopt a more extensive IAEA safeguards arrangement.

As required by Section 123 of the Atomic Energy Act, Congress has the opportunity to review U.S. nuclear cooperation agreements (also known as "123 agreements"). In the Saudi case, it will be critical for Congress to ask and get answers to key questions about the proliferation risks posed by the proposed agreement and—if necessary—vote to disapprove the deal or mandate additional nonproliferation obligations to ensure the agreement does not pave Riyadh’s pathway to the threshold of nuclear weapons.

Saudi Arabia’s Nuclear Plans

As a member of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), Saudi Arabia has the right to a peaceful nuclear program under IAEA safeguards. The country’s civil nuclear program is currently limited, but Riyadh has announced plans to build two large power reactors and develop capabilities necessary to produce reactor fuel, including a uranium enrichment program.

As part of its efforts to develop a civil nuclear program, Riyadh has been in a protracted negotiation with Washington on a nuclear cooperation agreement, which is required under the Atomic Energy Act for the transfer of U.S. nuclear technologies and materials. But the talks remained deadlocked for years, in part because of bipartisan U.S. opposition to Saudi Arabia’s insistence that any 123 agreement include the option for Riyadh to develop its own uranium enrichment capabilities and reticence to adopt and implement more stringent IAEA safeguards.

The United States has long argued that the NPT’s Article IV does not include the right to enrich uranium or reprocess plutonium. As part of its nonproliferation strategy, Washington sought to limit the spread of those technologies (which can be used to produce nuclear fuel or fissile material for nuclear weapons), particularly to states like Saudi Arabia that have threatened to develop nuclear weapons.

Washington has also consistently pushed for states to adopt an additional protocol to their safeguards agreements with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) as a condition of reaching a 123 agreement and advocated in other forums for the adoption of the additional protocol as an international best practice for preventing proliferation. The additional protocol was developed in the 1990s in the wake of Iraqi and North Korean illicit weaponization efforts. Those cases made it clear that standard IAEA safeguards agreements required by the NPT for non-nuclear-weapon states are insufficient for preventing determined proliferators.

The additional protocol addresses safeguards gaps by giving the IAEA access to sites that support a country’s nuclear program but do not house nuclear materials (such as centrifuge production facilities), additional information about a country’s nuclear program, and more investigative tools to investigate evidence of undeclared nuclear activities. It is not legally required, but, as of 2025, 144 states have an additional protocol in place. Riyadh’s reluctance to negotiate an additional protocol contributed to the impasse in negotiations on a 123 agreement and concerns about Saudi intentions to develop nuclear weapons.

A New Deal?

The impasse in the U.S.-Saudi talks on a 123 agreement appears to have ended in November with the Trump administration backsliding on key nonproliferation provisions in order to reach a deal. Although the text of the proposed 123 agreement has not yet been sent to the Hill, a report to Congress submitted in late November suggests that the Trump administration will allow some type of Saudi enrichment program. Furthermore, the mere existence of the report appears to confirm that the Trump administration is not requiring Saudi Arabia to negotiate an additional protocol with the IAEA.

Under Section 1264 of the fiscal year 2020 National Defense Authorization Act, the president cannot submit the required Nuclear Proliferation Assessment Statement (which details how a nuclear cooperation agreement meets the nine nonproliferation criteria set out in Section 123 of the Atomic Energy Act) to Congress unless a state has implemented an additional protocol. The requirement for an additional protocol can be waived, however, if the president submits to the “appropriate congressional committees a report describing the manner in which such agreement would advance the national security and defense interests of the United States and not contribute to the proliferation of nuclear weapons." The president submitted such a report on Saudi Arabia around Nov. 24, a week after announcing the framework.

According to the report (see excerpt, below), the White House views the deal as strengthening the domestic nuclear sector and contributing to U.S. security interests overseas. Specifically, U.S.-Saudi nuclear cooperation will “prevent strategic competition from seizing an opportunity to undermine United States national security interests for decades to come.” The report also argues that the United States must seize the opportunity to expand nuclear cooperation to “reestablish our leadership in the global civilian nuclear energy market and reap the benefits of expanded influence in foreign countries hosting our reactors.” As a host of U.S. bases, Saudi energy security and increased grid reliability also benefit U.S. national security, according to the report.

The Trump administration's report also claims that the proposed 123 agreement “will significantly reduce the risk of nuclear weapons proliferation” and that U.S. involvement in the Saudi program will increase transparency.

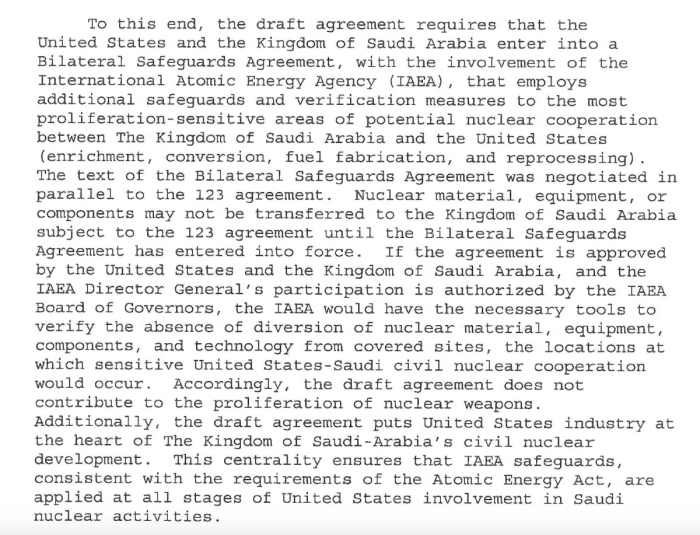

Nuclear cooperation can play an important role in reducing proliferation threats and providing insight into nuclear intentions, but the report to Congress fails to make a compelling case that the proposed agreement will not increase proliferation risks, particularly given that it does not insist on the internationally recognized best practices for safeguards, the Additional Protocol. Instead, the report notes that Saudi Arabia and the United States must enter into a “Bilateral Safeguards Agreement,” which will include additional verification measures and asserts that the agreement will give the IAEA the “necessary tools to verify the absence of diversion of nuclear material.”

But the report does not clarify what “unique terms” are included or explain how they compare to the thoroughness and intrusiveness of the additional protocol. Furthermore, the report suggests the bilateral safeguards agreement may be applied only at “locations at which sensitive United States-Saudi civil nuclear cooperation would occur.” This raises questions about safeguards at nuclear sites that are not part of the cooperative program. The additional protocol, by contrast, would not be similarly constrained to facilities where cooperative activities occur.

But even if the bilateral agreement is intrusive, U.S. support for an alternative arrangement sets a concerning precedent: other states may try to negotiate nationally-specific verification regimes rather than negotiating an additional protocol with the IAEA. This risks stalling, or even reversing, nearly two decades of efforts to universalize the additional protocol. Implementing specialized agreements could also prove to be overly burdensome for an agency that is already financially constrained.

The report also does not address how the United States would respond if Saudi Arabia, at some future point, misuses U.S. nuclear technologies and materials transferred under the proposed agreement. This is important to consider given Saudi Arabia’s open threats to build nuclear weapons—which is a greater risk now given that there is no nuclear agreement in place with Iran and further conflict could push Tehran closer to a bomb—and the apparent limitation of the bilateral safeguards agreement to specific sites.

The report does not explicitly state that the proposed agreement will allow a domestic Saudi-run enrichment program, but the text suggests it will. According to the report, the bilateral agreement “with the involvement” of the IAEA will employ “additional safeguards and verification measures to the most proliferation sensitive areas of potential nuclear cooperation between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United States (enrichment, conversion, fuel fabrication, and reprocessing).” The report goes on to say that “nuclear material, equipment, or components will not be transferred to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia subject to the 123 agreement until the proposed Bilateral Safeguards Agreement has entered into force.”

This suggests that once the bilateral safeguards agreement is in place, it will open the door for Saudi Arabia to acquire uranium enrichment technology or capabilities—possibly even from the United States. The administration’s report to Congress does not specify the scope, conditions, or what (if any) limits on uranium enrichment are included in the proposed deal. If, for instance, the proposed enrichment will take place in the United States with Saudi buy-in (an option previously considered), that is an important distinction that must be clarified. But even with restrictions and limits, it seems likely that Saudi Arabia will have a path to some type of uranium enrichment or access to knowledge about enrichment. Limiting the scope of the enrichment program or Saudi access to the technology may mitigate some of the proliferation risks, but not all, particularly if paired with insufficient safeguards.

What Can Congress Do?

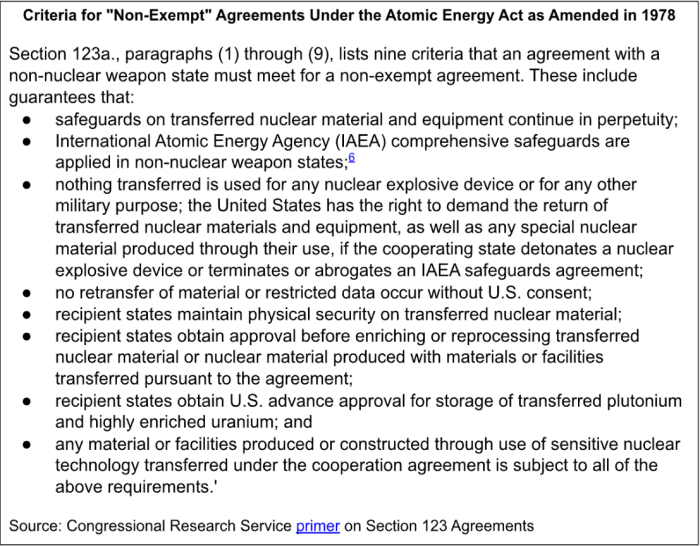

The 2020 NDAA states that the report on waiving the additional protocol must be delivered to Congress 90 days before a Nuclear Proliferation Assessment Statement (NPAS) can be submitted to Congress. The NPAS explains how a nuclear cooperation agreement meets nine nonproliferation obligations laid out in the Atomic Energy Act (see below for the nine criteria the NPAS assesses). The timing of this report suggests the administration could submit a 123 agreement to Congress as early as Feb. 22.

Once the NPAS is submitted, Congress has a total of 90 days in continuous session to consider the 123 agreement. After that period, it automatically becomes law unless Congress adopts a joint resolution opposing it. (The president can submit an agreement that does not meet the nonproliferation criteria. An exempt agreement requires a congressional joint resolution approving the agreement for it to become law, but there are no exempt 123 agreements in force.)

Congress must use the review period to thoroughly examine the agreement and, if necessary, call for the inclusion of additional nonproliferation provisions or vote to disapprove the deal. Traditionally, there has been long-standing bipartisan Congressional opposition to Saudi Arabia acquiring uranium enrichment, particularly without an additional protocol in place. When Secretary of State Marco Rubio served in the Senate, he was one of the leading voices insisting that any 123 agreement with Saudi Arabia to adhere to the so-called Gold Standard. He even co-led a bipartisan effort calling for a Congressional vote on any 123 agreement with Saudi Arabia.

But even without Rubio in the Senate, Trump is likely to encounter bipartisan resistance to abandoning the Gold Standard. When the Trump administration announced the nuclear cooperation framework in November, Republican Senator and chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (SFRC) James Risch said the Gold Standard “has to be included” in a 123 agreement with Saudi Arabia.

Similarly, ranking SFRC Democrat Jean Shaheen said “Saudi Arabia’s stated intention to acquire nuclear weapons if Iran does demands extreme caution” in how the United States approaches a 123 agreement. She went on to say that “any potential civilian nuclear cooperation agreement with Saudi Arabia must include enhanced inspections through an Additional Protocol to Saudi Arabia’s safeguards agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency. It is also critical that we hold Saudi Arabia to the ‘gold standard’ to ensure that Riyadh will not enrich uranium or reprocess plutonium.”

Senator Shaheen is right to demand “extreme caution” in approaching a U.S.-Saudi nuclear cooperation deal and not lose sight of Riyadh’s threats to weaponize. Specifically, Congress needs to probe the administration about the conditions of the bilateral safeguards agreement, ask why the proposed deal does not require the additional protocol, and question how the United States would respond if Saudi Arabia tried to exploit technologies and materials transferred under the deal for a weapons program.

Furthermore, Congress must consider the precedent this agreement sets and ask whether it undermines IAEA safeguards efforts. Will other states seek to move away from the additional protocol and seek tailored safeguards agreements? Is it sustainable for the IAEA to administer bilateral agreements rather than its own additional protocol? Will the Saudi agreement push other states insist on enrichment and reprocessing in future nuclear cooperation deals with the United States? The United Arab Emirates, for instance, agreed to a Gold Standard 123 agreement, but a provision in that deal allows for renegotiation if another state negotiates a nuclear cooperation agreement with more favorable terms.

Congress should also consider the impact on U.S. negotiations with Iran. Iran has long argued that it does not want to be singled out for restrictions. Will it be more challenging to negotiate enrichment limits (or a freeze on enrichment) and insist on the additional protocol if the United States is greenlighting a Saudi enrichment program with less intrusive safeguards? Does the deal enable or make it more difficult to consider regional options for addressing proliferation risks?

A Risky Precedent

Nuclear cooperation can be a positive mechanism for upholding nonproliferation norms and increasing transparency, but the devil is in the details. This initial report to Congress raises concerns that the Trump administration has not carefully considered the proliferation risks posed by its proposed nuclear cooperation agreement with Saudi Arabia or the precedent this agreement may set. It behooves Congress to provide that check and consider not just the implications for Saudi Arabia, but also the precedent that this deal will set, and vigorously examine the terms of the proposed 123 agreement.—KELSEY DAVENPORT, Director for Nonproliferation Policy

The End of New START and What’s Next?

Inside ACA

February 2026

For the first time in many decades, there are no legally-binding limits on U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals and there are no active negotiations to establish new nuclear arms control constraints.