Alicia Sanders-Zakre will be tweeting and blogging throughout the Nuclear Weapons Prohibition Talks at the United Nations. Follow her real-time updates at twitter.com/azakre.

Second Negotiating Session: June 15-July 7, 2017

UN Adopts Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapons

July 7, 2017

Today by a vote of 122-1 with 1 abstention, states adopted a historic treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons at the United Nations in New York. The Netherlands voted against the treaty and Singapore abstained.

Before adopting the treaty, Ambassador Elayne Whyte Gomez declared that “after many decades, we have managed to sow the first seeds of a world free of nuclear weapons.”

Despite the president’s initial suggestion to adopt the treaty by consensus, which received long applause from member states and civil society alike, the Netherlands called for a vote at the last minute.

The Netherlands explained in a statement after the vote that it could not support the treaty because it was incompatible with its obligations as a NATO member, it has provisions that are not verifiable and it could undermine the NPT.

The United States, the United Kingdom and France expressed strong opposition to the treaty in a July 7 joint statement released shortly after the vote. "This initiative clearly disregards the realities of the international security environment. Accession to the ban treaty is incompatible with the policy of nuclear deterrence, which has been essential to keeping the peace in Europe and North Asia for over 70 years."

Supporting states and civil society expressed small regrets that certain elements they had wanted to be included in the treaty were not, but overall welcomed the treaty as a significant and historic step towards nuclear disarmament.

“We hope that today marks the beginning of the end of the nuclear age. It is beyond question that nuclear weapons violate the laws of war and pose a clear danger to global security,” said Beatrice Fihn, executive director of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons in a July 7 statement.

“The new Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons is a historic step forward but, clearly, it is not an all-in-one solution to the dangers posed by nuclear weapons. Additional and difficult work lies ahead,” stated Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association in a July 7 press statement.

In a statement provided by the William Perry Project to the Arms Control Association, former U.S. Secretary of Defense William Perry said:

"The new UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons is an important step towards delegitimizing nuclear war as an acceptable risk of modern civilization. Though the treaty will not have the power to eliminate existing nuclear weapons, it provides a vision of a safer world, one that will require great purpose, persistence, and patience to make a reality. Nuclear catastrophe is one of the greatest existential threats facing society today, and we must dream in equal measure in order to imagine a world without these terrible weapons.

The UN treaty places a strong moral imperative against possessing nuclear weapons and gives a voice to some 130 non-nuclear weapons states who are equally affected by the existential risk of nuclear weapons. There is no one solution to this global threat, and there is much more work to be done beyond this treaty to reduce this risk. I call on nuclear-armed states to step up their participation in the fight against the nuclear threat by securing the eight remaining ratifications to enact the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, extending the New START agreement, continuing the critical work of the Nuclear Security Summits, and avoiding the unnecessary risk posed by introducing destabilizing new nuclear weapons. My hope is that this treaty will mark a sea change towards global support for the abolition of nuclear weapons. This global threat requires unified global action."

A more detailed story on the prohibition treaty will be available in the July/August issue of Arms Control Today.

Hiroshima Survivor Setsuko Thurlow Shares Her Wisdom with the Next Generation

July 6, 2017

One of the catalytic forces behind the pursuit of a Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in recent years have been the voices of the hibakusha, the survivors of the atomic bombings of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as the people across the globe who have been adversely affected by 70 years of nuclear weapons production and testing.

The preamble of the new prohibition treaty, which is expected to be adopted at UN headquarters in New York on July 7, notes “the unacceptable suffering of and harm caused to the victims of nuclear weapons (hibakusha), as well as those affected by the testing of nuclear weapons” and the preamble also recognizes that nuclear weapons pose “grave implications for … the health of future generations and have a disproportionate impact on women and girls, including as a result of ionizing radiation.”

One of the leading hibakusha voices and strongest and most tireless advocates for a legally-binding treaty to prohibit nuclear weapons is Setsuko Thurlow, who was voted the "2015 Arms Control Person of the Year.”

Earlier this spring, Thurlow was contacted by 14-year old Nola James, a high school student living in Washington, D.C. who asked Thurlow to answer questions about her experience and advice for the next generation of young people concerned about the dangers of nuclear weapons.

Thurlow was 13 years old when the “Fat Man” bomb was dropped on the city of Hiroshima. With the permission of Ms. James, Thurlow has shared the questions and her responses with ArmsControlNow.org.

- ALICIA SANDERS-ZAKRE and DARYL KIMBALL

Q. What has motivated you to keep sharing with others your very difficult experience, especially after the hate and threats you received when you were in the U.S.?

After the occupation of Japan by the United States Army after World War II, when more information became available about the atomic bombings, it was the beginning of a new age of awareness in Japan about the dangers of nuclear weapons. This was especially true because the Americans and the Russians got into a nuclear arms race and both were conducting nuclear weapons testing in the atmosphere.

So those of us in Hiroshima who lived through the atomic bombing and who lost loved ones in the war got the feeling that we needed to do something to prevent the atomic bombings from happening again. We began to realize that we had to use our experience to speak to the world about the dangers of the atomic bomb.

At that time, in the 1950s and 1960s, Hiroshima became very much a pacifist city, and its citizens were beginning to speak out for peace. Hiroshima has become a peace city driven by the spirit of its citizens and the atomic bomb survivors like me. I grew up there and was among those who began to realize that I needed to overcome my fears and to speak out for the loved ones that I lost in the bombing. Today in Hiroshima, the government of the City of Hiroshima has peace promotion division at City Hall that runs the Hiroshima Peace and Culture Foundation and it runs the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Museum and it hosts the Mayors for Peace Organization that works with city leaders around the world, including with the Mayors of Washington D.C. and New York, for the elimination of nuclear weapons.

Yes, when I came to the United States to study I was receiving unsigned hate letters because of my critical comments about the U.S. hydrogen bomb tests over the Pacific Islands. After I began receiving these letters, I spent about a week thinking, of soul searching, and I came out with a stronger sense of responsibility that I needed to continue to keep speaking out. If I, a survivor of the first atomic bombing, was not going to speak out, who was going to speak out to help prevent such a horrible thing from happening to anyone else, ever again?

Back then and even now, I had strong memories of what happened that day in August of 1945 when I was just 13 years old. All of my memories and the images of those who were killed keep driving me to do what I do, to speak out for peace and a world free of nuclear weapons.

In particular, I remember my four year old nephew who kept asking for water after the bombing. He was just a chunk of flesh crying out for help and we could not do anything to help him. I still remember him very vividly.

This little boy’s image has come to represent in my mind all the innocent children who could be wiped out if there was another nuclear war.

Our conscience does not allow us to see this happening to other human being. No matter how difficult or painful it is for me, I just feel I have a responsibility to speak out.

Over time I learned to become less fearful and it is the image of my relatives and loved one and my emotional connection to them that helps me keep me going on. Its this emotion and the knowledge of what could happen that keep me going on.

Q. What would you say to young people who want to help but don't know how?

First we all have to know about the issue, the dangers of nuclear weapons. We have to study and read and learn about the problem of nuclear weapons and the history so we can understand better what needs to be done. At the same time, we must find ways not to become so horrified and overwhelmed that we are unable to take action.

No one can solve this problem alone, but together we can change things. I suggest young people start by joining an existing peace and nuclear disarmament group or you can help form your own group with others who are concerned to learn more about the problem and to find ways to take action. If you need help or guidance, your history or social studies teacher or a friend can help you find a local peace group and point you to some information to learn more.

When you feel confident enough, you can speak out and take action by doing things like making appointments for meetings with your legislators in Congress, writing letters to the editor to newspapers about the subject and what can be done, and to help make this issue visible to others around you because it a problem that affects all of us.

Citizens in the United States have a special role and responsibility because their country was the first to use nuclear weapons in war and because the United States is an influential country and is a democracy where its people have a strong voice in what its leaders do.

- Setsuko Thurlow, Toronto, Canada, May 4, 2017

Nuclear Weapons Prohibition Treaty Takes Final Form

July 4, 2017

The third and likely the penultimate draft treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons was released Monday evening, four days before the scheduled deadline for the July 7 negotiating conference, when the 100 + delegations aim to adopt the agreement.

The new text is a product of a week of intense small working group discussions chaired by representatives from Ireland, Chile and Thailand as well as president of the negotiations, Ambassador Gomez. The working groups presented revised versions of key articles in an open plenary on June 30, many of which were lightly edited and included in the newest draft.

Reaching Critical Will’s July 3 “Ban Daily” provides analysis of the working groups’ draft articles.

Key changes to the new draft are listed below, although it should be noted that this list of adjustments to the previous version of the draft text is not exhaustive.

Preamble

The preamble has not been changed, despite calls from several civil society members, including Ray Acheson in a June 30 Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists article, to remove paragraph 21 recognizing states-parties’ inalienable right to nuclear energy.

Article 1: Prohibitions

The biggest change to Article 1 in the July 3 draft is the inclusion of a prohibition on threat of use, which over a dozen states supported during the initial week of the second round of negotiations.

In addition, the two paragraphs in the June 27 draft have been merged into one, as several states suggested during open plenary sessions. The earlier drafts included a prohibition on “nuclear weapon test explosions or any other nuclear test explosion,” while this draft simply prohibits a “test” of a “nuclear explosive device.”

Article 2: Declarations

Article 2 in the draft text is very similar to the revisions presented by the working group on Friday. Each state party must declare if it had nuclear weapons but eliminated them before the entry into force of the treaty, as well as if it currently possesses nuclear weapons or has nuclear weapons stationed on its territory.

These added declarations align with the revisions to Article 4 of the treaty, which now includes a “destroy and join” accession pathway for nuclear weapons states and an obligation to remove any nuclear weapons from its territory.

The new draft deletes the obligation in the June 27 draft to declare if a state party’s nuclear material is under IAEA safeguards, which is rendered unnecessary by the revisions to Article 3 in the new text.

Article 3: Safeguards

Article 3 retains the paragraph in the June 27 text stipulating that states parties must maintain existing safeguards “without prejudice to any high level of safeguards” in the future.

It adds that states parties without an IAEA INFCIRC 153 safeguards agreement shall conclude such an agreement “no later than 18 months from the entry into force of this Treaty.”

This addition answers concerns raised by several states that the June 27 text did not require states parties to have safeguards agreements. However, the reference to INFCIRC 153 may cause problems, as indicated by the debate over the reference to INFICRC 153 in the May 22 draft Annex. Some states would like to see stronger safeguards agreements required by the draft text, such as the IAEA Additional Protocol, which Brazil among others, would not accept.

Article 4: Towards the total elimination of nuclear weapons

Article 4 has been adjusted to include two pathways for nuclear weapons states to join the treaty in the future.

Paragraph 1 of Article 4 is the added “destroy and join” option. It indicates that any state that had nuclear weapons after July 7, 2017, but eliminated them before it joined the treaty should cooperate with a “competent international authority” designated by the treaty to verify the dismantlement of its arsenal, as well as conclude a safeguards agreement with the IAEA to verify that nuclear materials are not diverted from peaceful to weapons purposes.

The “join and destroy” option in paragraph 2 of Article 4 is remains similar to that in the June 27 draft.

Article 4 in the July 3 draft adds an additional obligation to remove any nuclear weapons stationed on a state’s territory, as Austria and other states had suggested.

An added paragraph 6 charges states parties with designating an international authority to oversee the dismantlement of nuclear weapons.

Article 5: National implementation

Article 5 of the July 3 draft deletes the phrase “in accordance with constitutional practices” regarding national implementation obligations, which several states recommended during open plenaries.

Article 5, on additional measures, in the June 27 draft has been removed as a separate article, although its core has been incorporated into Article 8(1)(c), by allowing for the adoption of additional protocols to the treaty on “measures for the verified, time-bound and irreversible elimination of nuclear-weapon programmes” at future meetings of states parties.

Article 6: Victim assistance and environmental remediation

Article 6 remains largely unchanged except for the addition of paragraph 3, stating that “the obligations under paragraphs 1 and 2 above shall be without prejudice to the duties and obligations of any other States under International Law or bilateral agreements.”

Calls by many civil society members to strengthen the treaty’s provisions on victim assistance and environmental remediation seem to be addressed by a strengthened Article 7 instead of a revised Article 6.

Article 7: International cooperation and assistance

The July 3 draft adds more detailed language on the type of assistance (technical, material and financial) to be provided to victims of use and testing. The added paragraph 4 mandates mildly stronger obligations for victim assistance: “Each State Party in a position to do so shall provide assistance for the victims of the use or testing of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices.”

However, the article still claims that only states “in a position to do so” are obligated to provide assistance, language several states and civil society observers had suggested removing from the article. The article also does not obligate the perpetrators of nuclear use and testing to bear the brunt of the assistance to victims, which had been a popular idea at public plenaries.

Article 10: Amendments

Article 10 no longer calls for the convening of an “amendment conference” to consider amendments, and suggests that meetings of states parties be the appropriate forum instead.

Article 13: Signature

As initially proposed by Austria, a revision to Article 13 indicates that the new treaty would open for signature on September 19 at the United Nations in New York.

Article 17: Duration and withdrawal

Heeding calls from several states and outside observers to make the withdrawal period longer, the new draft extends the withdrawal period to 12 months, from the June 27 draft’s three months, but does not require an extraordinary meeting of states parties in the event that a state withdraws.

Article 18: Relationship with other agreements

This article remines unchanged, despite concerns raised by the Netherlands that it could be interpreted to mean that the nuclear weapons prohibition treaty takes legal precedence over the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT).

Final steps

After receiving comments on the most recent draft from their capitals, delegations are scheduled to agree to any final changes to the treaty by the end of the day Wednesday or early Thursday, which would allow enough time to complete official translations of the text in time for its adoption on Friday by the conference.

States anticipate the treaty will be adopted on Friday, despite the short four-week negotiating period. Although Algeria raised a concern in Monday’s open plenary that there was not sufficient time to send the new text back to capitals for approval and that it might be difficult to meet the July 7 deadline, most states countered that it was possible to conclude the treaty by Friday.

States Face Time Crunch, Disagreements as Final Week Approaches

June 29, 2017

Negotiations on a treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons have entered a critical phase as states work to finalize a treaty by early next week and adopt it by July 7.

In a brief open plenary on Thursday, President Elayne Gomez acknowledged that a significant amount of work remains, stating that “we can deem ourselves to be permanently convened” until negotiations conclude.

The second revised draft treaty text was released Wednesday. See the post below for an analysis of the changes in the new text from the first draft text released May 22.

Although states lauded improvements from the first draft text to the second in their statements in an open plenary Wednesday afternoon, there was still considerable disagreement about key issues, as well as resentment from some states whose suggested revisions had not been included in the new draft.

There also appear to be a number of irreconcilable disagreements about the wording of the preamble. Some delegations, including Egypt, which has not signed or ratified the CTBT, want to remove the reference in the preamble to the “vital importance of the CTBT and its verification regime.” Many other delegations support the inclusion of such a reference.

Nongovernmental observers, including Reaching Critical Will, raised important objections to the new paragraph in the revised preamble that claims that there is an “inalienable right” to “peaceful uses” of nuclear energy. The focus of this treaty, they argue, should be on delegitimizing nuclear weapons, and not on legitimizing risky and inherently dangerous technologies that can be misused to produce fissile material and build nuclear weapons.

Several states, including Brazil and Algeria, expressed regret that there had been no additions to Article 1 on general obligations. Adding a prohibition on the “threat of use” had been an idea advanced by several delegations during the first week of the second round of negotiations, but the chair declined to include it in the next draft.

Cuba was among a few states continuing to advocate for the inclusion of a prohibition on transit.

Egypt and a handful of other states continue to suggest that the prohibition on nuclear weapons test explosions should, unlike the 1996 CTBT, include a prohibition on “subcritical experiments,” which are not nuclear explosions but which can and are used for nuclear weapons related research and development. Such subcritical experiments would presumably be prohibited by other provision in the treaty on nuclear weapon “development. “

There is considerable resistance to adding a prohibition on financing in the prohibited activities section of the treaty, in part because of verification and definitional issues.

Articles 2-5, however, continue to pose the most significant challenge to the conference. Many private discussions have focused on revising and refining the treaty’s provisions on declarations, safeguards and accession of nuclear weapons states to the treaty.

In the open session on Wednesday, Austria and Brazil argued that the list of declarations in Article 2 should be expanded to include a declaration of any nuclear weapons stationed on a state-party’s territory, which would align with the prohibition in Article 1 of “stationing, installment or deployment” of nuclear weapons. This declaration, and its corresponding Article 1 prohibition, would challenge NATO states that host U.S. nuclear weapons on their soil.

While some states appreciated the simplicity and elegance of the revised Article 3, several states, including Austria, noted that it was weaker than its predecessor because it didn’t encourage states to pursue additional safeguards obligations. New Zealand and Brazil suggested reincorporating the annex on safeguards from the first draft back into the final text.

Several delegations, including CARICOM, and nongovernmental experts called for a strengthening of the victim assistance and environmental remediation provisions in Article 7. Currently, the draft text calls on “states in a position to do so” to provide such assistance.

Indeed, given that the genesis of the push for the negotiation of a treaty to ban nuclear weapons derives from the concern about the effects of nuclear weapons testing, production, and use, it should be an obligation of states parties to provide (and report on) assistance to those who have been affected by nuclear detonations and nuclear weapons production in their territory, and those who might survive such events in the future.

On institutional measures, states including Ecuador and Palestine continued to insist on the removal of provisions allowing withdrawal from the treaty, while others, including Brazil and Mexico, argued that it should be far more difficult to withdraw from the treaty than the second draft would allow.

Austria suggested that there should be a date set for the opening for signature for the treaty, such as September 20, 2017, a proposal that is also supported by New Zealand and Brazil.

While leading negotiating states, such as Austria, Brazil, Ireland, Mexico and New Zealand seem to have reached consensus on several key issues, other active participants in the negotiations continue to ardently disagree, including Iran, Ecuador and the Netherlands, which is among the five NATO member states that host U.S. nuclear gravity bombs on their soil.

The Clock Is Ticking

As states repeatedly noted during Wednesday’s open plenary, time is of the essence. If a treaty is to be adopted by July 7, it will, ideally, need to be finalized at least a day before the scheduled end of the conference on July 7 in order to give delegates sufficient time to send the text back to their capitals for final approval. This makes the next four to five days especially important.

In the coming days of closed door consultations, states will need to forge compromises and loosen their rigidly held positions—and the President of the Conference will need to take a more active role resolving differences—if the 100+ states represented at the conference are to achieve agreement on a much-anticipated treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons. —ALICIA SANDERS-ZAKRE, with assistance from DARYL G. KIMBALL

What’s New in the 2nd Draft Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

June 27, 2017

The second draft text on a treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons was released by the President of the Conference, Elayne Whyte Gomez of Costa Rica, on Tuesday June 27.

Overall, the revised text is cleaner and clearer than the first May 22 draft and reflects many popular proposals introduced during the first week of the second round of negotiations. It is our assessment that the President’s new draft text addresses the major concerns and suggestions from the negotiating parties and moves the process closer to the adoption of a text by the end of the negotiating session on July 7.

The title has been changed and the preamble is longer, but the biggest revisions and improvements were to Articles 2-5 on declarations, safeguards, the elimination of nuclear arsenals, and “further effective measures” towards disarmament.

Key changes from the first to the second draft text are listed and explained below.

Title

The title of the text has been changed from “convention” to “treaty,” as many states requested during the second round of negotiations, to better reflect the intent and scope of the instrument.

Preamble

The preamble has swelled from 14 paragraphs in the first (May 22) draft text to 24 paragraphs in the June 27 text. It includes new language recognizing the disproportionate impact of nuclear weapons on indigenous people, encouraging the participation of women in disarmament, referencing the first General Assembly resolution calling for the elimination of nuclear weapons, and affirming the right of all states to the peaceful uses of nuclear energy.

Article 1: General obligations

States’ obligations under Article 1 of the treaty have remained largely the same, despite calls from some states to include a prohibition on transit, financing and threat of use.

Delegitimizing the threat of use of nuclear weapons, and deterrence theory more broadly, is covered in the preamble, which recognizes in paragraph 12 that “states must refrain... from the threat or use of force” and expresses concern in paragraph 14 about the “continued reliance on nuclear weapons in military and security concepts.”

Article 2: Declarations

Article 2 of the new draft requires that all states parties make a declaration about their possession and elimination of nuclear weapons and nuclear explosive devises before the entry into force of the treaty for that state. This draft eliminates the distinction in the May 22 text between states that possessed nuclear weapons before and after December 5, 2001 by removing any reference to a specific date.

Article 3: Safeguards

Article 3 on safeguards has been significantly improved to reflect Ireland’s popular proposal during the second round of negotiations that is designed to reinforce existing safeguards commitments and allow for the evolution of safeguards over time.

The revised Article 3 requires that states parties maintain the safeguards they are party to when they join the treaty, and adopt stronger safeguards as they become available in the future.

The Annex on safeguards in the May 22 draft, as well as its specific reference to INFCIRC/153, a basic safeguards agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), have been eliminated.

Article 4: Towards the total elimination of nuclear weapons

Article 4 on the accession of nuclear weapons states to the treaty has also been significantly revised. Unlike the May 22 draft, the new draft allows states to join the treaty before eliminating their nuclear weapons. However, as soon as they join, they must remove all nuclear weapons from operational status and submit, within 60 days, “a time-bound plan for the verified and irreversible destruction of its nuclear weapons.”

Article 4 also requires that after the “dismantlement” of nuclear weapons, state parties must reach an agreement with the IAEA to prevent “the diversion of nuclear energy from peaceful uses to nuclear weapons,” which would likely be similar to agreements of nonnuclear weapons states under the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

During the negotiations, several states raised the point that IAEA does not have the capacity or the mandate to verify the destruction of nuclear weapons. Therefore, Article 4 charges the IAEA with the verification of the “correctness and completeness” of the states’ “declared inventory” of nuclear weapons but leaves the responsibility of verifying the destruction of nuclear weapons to “a competent international authority” designated by the States Parties.

It is not clear which existing international authority would have the ability or the mandate to verify the destruction of nuclear weapons. Paragraph 4 of Article 4 is sufficiently flexible to allow for a new organization which may be created in the future or perhaps the IAEA, should its capability and mandate be expanded in the future, to take on this responsibility.

Article 5: Additional measures

Article 5 has remained almost entirely the same, despite calls from some states at the second round of negotiations to eliminate it.

The Netherlands raised the concern that Article 5 is intended to make meetings of states parties to the prohibition treaty an alternate negotiating forum to the Conference on Disarmament.

While New Zealand and other states have stated that is not the intent of the article, as drafted, it does allow for the adoption of additional protocols, which could theoretically include disarmament proposals traditionally floated at the Conference on Disarmament, including legally-binding negative nuclear security assurances for nonnuclear weapon states.

The creation of an alternative negotiating forum could confirm fears expressed by nuclear weapons states that the prohibition treaty would distract from existing disarmament machinery, particularly the deadlocked Conference on Disarmament in Geneva. Alternatively, by creating another potential forum for the exchange and discussion of effective disarmament measures, the new treaty could provide a welcome and much-needed tool to help advance progress on nuclear disarmament.

Article 9: Meeting of States Parties

Article 9 in the June 27 draft delineates which topics states should discuss at meetings of states parties. It stipulates that review conferences will be convened every six years, instead of every five years, to better align with the schedule of biennial meetings of states parties.

It has also been updated to allow for extraordinary meetings of states parties.

Article 11: Amendments

Article 11 in the new draft calls for the convening of an Amendment Conference to consider amendments to the treaty. In the May 22 draft, amendments were to be adopted by a two-thirds majority at a meeting of states parties or review conference.

Article 16: Entry into force

The number of states required to ratify the treaty in order for it to enter into force has increased by ten, from forty to fifty states. This change signals a compromise between many states who had expressed satisfaction with the 40 state requirement in the May 22 draft and Sweden, who called for a 65 state ratifications threshold.

There is what appears to be a small typo in the June 27 draft text. The second paragraph references “fortieth instrument of ratification” when it should probably read “fiftieth instrument of ratification” to be consistent with the change in the first paragraph of the article.

Article 19: Relations with other agreements

Article 19 has been revised to follow Arms Trade Treaty Article 26 paragraph 1, as Malaysia suggested and many states supported during the second round of negotiations. It removes the previous reference to states’ rights and obligations under the NPT to simply state that the implementation of this treaty should not conflict with states’ obligations under existing or future agreements.

The week ahead

Many of the negotiating sessions this week are expected to be closed to civil society, according to the timetable released on Friday, June 16, but there will be two open sessions, one on Thursday morning and another on Friday afternoon.

Review of first draft ban treaty to conclude today

June 21, 2017

As participants in the negotiations on a treaty to ban nuclear weapons near the end of their review of the first draft text released on May 22, expect a stronger draft to emerge within the next couple of days.

A revised draft preamble was already released by the president of the negotiations on Tuesday evening.

Below is a summary of key revisions discussed during the review of the first draft text. A compilation of all revisions submitted to the president are available on the UN’s website.

The Revisions

Title: Many states took issue with the labeling of the draft as a convention, arguing instead that it should be called a treaty to better reflect its intended scope as a simple prohibition.

Preamble: States put forth proposals to strengthen existing preamble elements, including a reference to international humanitarian law, eventual elimination of nuclear weapons and the gendered impact of nuclear weapons.

Others called for adding in new elements to the preamble, including references to relevant UN General Assembly disarmament resolutions, a reference to the 1996 International Court of Justice Advisory Opinion, the encouragement of education on nuclear risks, the role of women in disarmament and a reference to the right of all states to peaceful nuclear energy.

The new draft preamble released on Tuesday evening incorporated some of these suggestions, including an expanded reference to international humanitarian law and the role of women in disarmament.

General Obligations (Article 1): Over a dozen states advocated for the inclusion of a prohibition on the threat of use of nuclear weapons to explicitly delegitimize deterrence, although Austria, Malaysia and Switzerland countered that a threat of use prohibition is already implicitly included in the prohibition on use.

States disagreed about the inclusion of prohibitions on financing and transit of nuclear weapons. As during the March negotiations, Iran and Cuba were among those to call for their inclusion, while Brazil and Mexico expressed concern that verifying such prohibitions would prove difficult. Some states also requested the removal of the prohibition of testing from the treaty because it could undermine the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty by restating the prohibitions in the CTBT without including a reference to the treaty’s monitoring system.

Safeguards and Nuclear Weapons States Accession (Articles 2-5): Many states, including Ireland, agreed that Article 3 should not reference INFCIRC/153 and should instead remain flexible to adapt to the strongest safeguards that become available in the future.

Chile, Switzerland and New Zealand argued that states should be required to adopt the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Additional Protocol as part of Article 3.

New Zealand, Austria, Ireland, Mexico and South Africa, among others, suggested that the treaty require nuclear weapons states to destroy their arsenals after signing the prohibition treaty. South Africa’s popular proposal on this topic would eliminate Article 3 and Annex A in favor of simpler safeguards language. At its core, South Africa’s new Articles 2 and 4 would require states to declare their nuclear weapons, commit to destroy them and then submit a final declaration upon elimination, subject to IAEA verification.

The Netherlands objected to Article 5 of the draft text on further effective measures on disarmament, claiming that it could pose a threat to the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) by creating an alternate forum to the Conference on Disarmament to negotiate disarmament proposals, although New Zealand and Argentina were among those to argue that would not be the intent of Article 5.

Core Prohibitions (Article 6): Egypt, Ecuador and Iran were among those to argue that the responsibility for assistance to victims of nuclear weapons detonations ought to be borne primarily by those states who conducted the detonations. Ireland, the Philippines and others called for strengthening the obligation for environmental remediation.

Implementation (Articles 7-10): Malaysia was among many to express concern about the cost of future meetings of states parties, as those who typically bear the majority of these costs are absent from this convention. Switzerland and others requested that the treaty allow for special meetings of states parties.

Institutional Arrangements (Articles 11-21): Many states agreed that amendments would need broader support than the draft text’s two-thirds approval requirement from states parties before being adopted.

States continued to disagree about the number of ratifications required for entry into force of the treaty, with Brazil and New Zealand maintaining the draft text’s 40 ratifications would be sufficient and Sweden advocating for a 65-state ratification minimum.

Article 19 on the prohibition treaty’s relationship to other treaties will likely undergo significant revision. There was broad support for Malaysia’s proposal to model this article on Article 26, Paragraph 1 of the Arms Trade Treaty. The Netherlands posited that Article 19 should require states parties to the prohibition treaty to adhere to the NPT.

What’s Next

Discussion will conclude on Articles 11-21 today, after which the president of the negotiations will release a second draft treaty for review. The challenge now, stated Ambassador Gomez at the conclusion of Tuesday’s negotiations, is to consolidate the many proposed revisions and additions into one concise document.

A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall

June 19, 2017

Spirits were high as rain poured down on protesters marching in support of the ongoing UN negotiations to prohibit nuclear weapons in New York on Saturday.

Chanting “rain is better than nuclear fallout,” and singing “Down by the Riverside,” protestors spanning more than two city blocks marched from Bryant Park to the United Nations.

Ambassador Elayne Whyte Gomez, president of the negotiations, was among those attending the rally organized by the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

The march follows a long history of women-led protests against nuclear weapons. These include a nationwide protest in 1961, where 500,000 people in 60 cities marched against nuclear testing and the famous 1982 march, which drew one million people to Central Park to demand a freeze to the nuclear arms race. The 1961 march was organized by Women’s Strike for Peace, which also helped to coordinate the 1982 march.

The role of women in disarmament has been a key theme throughout the nuclear ban treaty negotiations. As I tweeted on Friday, several states have called for a strengthened reference to the role of women in disarmament in the preamble of the nuclear prohibition treaty.

In a recent Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists article, Elisabeth Eaves discusses the prominent role that women have played and continued to play in nuclear disarmament.

The rally featured exclusively female speakers and performers, including Kozue Akibayahsi, the president of the Women’s International League of Peace and Freedom, Sharon Dolev, founder of the Israeli Disarmament Movement and Cora Weiss, a leader of the former Women’s Strike for Peace. Speakers had to cut their remarks short however, as the crowd dwindled as the storm relentlessly continued.

Over 170 other marches and rallies in support of the UN nuclear prohibition negotiations took place across the United States and internationally on Saturday, according to the Women’s League for International Peace and Freedom.

What to Expect As Round Two Of the Nuclear Ban Talks Begin

June 15, 2017

The historic nuclear prohibition treaty currently under negotiation could be “the missing piece in the puzzle” of nuclear disarmament architecture, claimed the representative from Brazil at the opening of the final negotiations on the treaty, which began this morning and will end July 7.

States repeatedly expressed support for the draft treaty of the Convention for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons circulated by the negotiation’s president on May 22, claiming it forms a strong basis for future negotiations, but also offered suggestions for revision of the preamble.

Over the course of the next few weeks, states will revise the initial draft with the goal of finalizing a treaty by the session’s end.

How Did We Get to this Point?

The events that have led to the possible conclusion of a nuclear weapons prohibition treaty have been years in the making.

Following an October 2016 UN General Assembly First Committee resolution, nearly 130 states met in New York from March 27-31 for the first round of negotiations. The president of the negotiations, Elayne Whyte Gomez of Costa Rica, produced a draft treaty on May 22 based on these discussions. The May 22 draft treaty text reflects many of the shared opinions among negotiating states, and intentionally leaves out more controversial items to be considered for inclusion during the June 15-July 7 round of negotiations.

The initiative has faced considerable opposition from nuclear weapons states and many NATO members, who contend that it might undermine a landmark non-proliferation treaty, the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), and distract from other practical disarmament steps.

The prohibition treaty’s many supporters argue that the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of nuclear use merit urgent additional steps on disarmament, including a new treaty to strengthen the legal and normative basis against nuclear weapons possession and use and for a process leading to the elimination of nuclear weapons.

The prohibition negotiations have the support of new UN High Representative for Disarmament Affairs Izumi Nakamitsu, who, in a May 22 email, stated: “The UN Office for Disarmament Affairs supports these negotiations as a step towards the universally desired goal of a world free of nuclear weapons,” adding that “divisions among States will remain and continue to grow without demonstrable further progress toward the global elimination of nuclear weapons. The States possessing nuclear weapons continue to bear the largest burden for leading efforts in this regard. In today’s deteriorating international security situation, no one should be satisfied with the status quo.”

The Schedule

Today and tomorrow, participating states will express their general views on the draft text. On Saturday, June 17, members of civil society will convene for the Women’s March and Rally to Ban the Bomb, starting at 12PM at Bryant Park.

From June 19-23, states will discuss the draft text thematically, with sessions devoted to the preamble, positive obligations, core prohibitions, implementation and institutional arrangements and universality and final provisions.

Key Issues

The following topics are among those likely to be discussed and revised during the upcoming week of negotiations. In an article in the June issue of Arms Control Today, John Burroughs provides a comprehensive overview of the issues in the draft text.

Core Prohibitions (Article 1): The May 22 draft text calls for a prohibition on the development, production, manufacture, acquisition, possession, stockpiling, transfer, use, testing, stationing, installation and deployment of nuclear weapons, as well as assistance with any prohibited activities.

Some states may argue for the inclusion of a prohibition on the threat of use, transit and financing of nuclear weapons in the final treaty, all of which were mentioned repeatedly in negotiations in March. The Women’s International League for Peace supported the inclusion of these prohibitions in a June briefing paper.

Others, including Austria and Mexico, two leading treaty supporters who did not support the prohibition of testing in the first round of negotiations, may advocate for removing testing from the core prohibitions. Many would like to see a stronger affirmation that the nuclear prohibition treaty is not a substitute for the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, which includes an International Monitoring System to detect nuclear tests.

A former senior U.S. nonproliferation and disarmament official, Jon Wolfsthal, in a May 22 blog post, noted that the prohibition of testing in the May 22 draft treaty creates an uncertain relationship with the CTBT.

Safeguards (Article 3 and Annex): The safeguards provisions outlined in Article 3 and the attached annex will be likely be debated and revised during the second round of negotiations due to concerns experts have raised about the current phrasing.

Australian safeguards expert John Carlson in a May 26 article observed that the safeguards in the treaty should not be tied to INFCIRC/153, as it prevents the treaty from adopting stronger safeguards as they evolve over time. The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons seconded this point in a June briefing paper.

Sweden and Switzerland had called for requiring states-parties to the treaty to adopt the IAEA Additional Protocol in the first negotiations, and may continue to advocate for the inclusion of this stronger verification standard, although Brazil, a leading treaty negotiator, would likely oppose it.

Accession of Nuclear Weapons States (Articles 4, 5 and non-paper): There will likely be questions and proposals for clarification about the path for accession by nuclear weapons states to the treaty. Article 4 of the May 22 draft text, and the attached non-paper, seem to indicate that nuclear weapons states must eliminate their nuclear arsenals first and then sign the prohibition treaty and adopt verification provisions, following the model of South Africa’s accession to the NPT.

Pointing to some of the challenges with South Africa’s NPT accession, Zia Mian in an June Arms Control Today article argues that it would be much easier to verify the dismantlement of nuclear arsenals if states declared their arsenals when signing the treaty and then worked with the IAEA to verify dismantlement instead of disarming beforehand.

The negotiating parties may also seek to clarify the aims and goals of Article 5. Some observers have interpreted Article 5 as an alternative and more flexible path to accession without specified verification provisions. Others see it as a way to negotiate other disarmament proposals outside of the Conference on Disarmament, as additional protocols to the treaty.

States will likely continue to debate and clarify these and other elements of the emerging treaty as negotiations continue.

The second day of negotiations will begin at 10 AM on Friday, June 16 and will be broadcast on UN Web TV.

First Negotiating Session: March 27-31, 2017

Day 5—Institutional arrangements and looking ahead

March 31, 2017

The last day of the first week of negotiations on a treaty banning nuclear weapons consisted of a discussion of institutional arrangements and reviewed the program of work for the initial week of the second round of negotiations in June.

Institutional Arrangements:

Institutional Arrangements:

Entry into force

Almost all states expressed support for simple entry into force provisions, specifying that particular states should not have to ratify the treaty before its entry into force in order to avoid the barriers to ratification faced by the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) due to its requirement for ratification by Annex 2 states. Many states did not precisely indicate how many states should be required to ratify the treaty before its entry into force although several, including Austria, suggested around 30 and Sweden proposed 80.

Reservations and withdrawal

Many states, including New Zealand and Ireland, agreed that states should not be able to have reservations to the treaty but should be able to withdraw, under certain conditions. Mexico called for two requirements for withdrawal from the treaty–that withdrawal does not occur during armed conflict and that states can only withdraw once 15 years have passed since the treaty entered into force. South Africa, among other states, suggested that the treaty should follow standard withdrawal and reservation provisions, consistent with the Vienna Convention.

Meetings of states parties

States generally agreed that states parties should meet annually and have a review conference every five years although Malaysia suggested that such frequent meetings would not be necessary until nuclear weapons states will have acceded to the treaty.

Accession of states

While some states, including Austria, put forth that nuclear weapons states should not be allowed to join the treaty without first eliminating their arsenals, many states supported and even called for nuclear weapons states to accede to the nuclear prohibition treaty before elimination, as long as they provided a plan to disarmament upon signature.

Depository and secretariat

Many states called for the United Nations secretary-general to be the depository of the treaty. Brazil doubted the necessity of a secretariat for the treaty, but the Philippines countered the secretariat could play an important role in facilitating review conferences and assistance.

Victim assistance

Several states, including Fiji, who referenced its own country’s suffering due to nuclear testing, called for institutional mechanisms to provide assistance to victims of nuclear use and testing. Mexico, among others, while indicating its support for the idea, expressed uncertainty about how to implement this provision.

Indicative timetable for June 15-23

After the conclusion of the session on institutional arrangements, Elayne Whyte Gomez, president of the conference, presented the draft indicative timetable for the first week of the second round of negotiations in June. Gomez told states that she would prepare and circulate a draft instrument likely in late May or early June for states to review. Expressing satisfaction with the contribution of civil society to the first round of negotiations, Gomez proposed incorporating the voices of academics and civil society members in a similar fashion in June.

As delegates left the conference room, members of civil society handed them paper cranes and thanked them for their participation.

Day 4—Perspectives from Civil Society and Academia

March 30, 2017

The penultimate day of the first week of negotiations on a treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons highlighted civil society members and academics who provided expertise and alternative opinions on divisive core provisions.

The day featured two panels each consisting of three representatives from civil society and academia who delivered remarks then took questions and comments from delegates.

Ray Acheson, of the Women’s International League of Peace and Freedom, John Burroughs, representing the International Association of Lawyers against Nuclear Arms and Louis Maresca, of the International Committee of the Red Cross spoke on the first panel. In the afternoon, Richard Moyes of Article 36, Gaukhar Mukhatzhanova of the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies and Zia Mian of Princeton University formed a second panel.

Focusing on the preamble, panelists in the first session reiterated the consensus on including the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons, and also suggested adding a reference to the right to life.

Focusing on the preamble, panelists in the first session reiterated the consensus on including the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons, and also suggested adding a reference to the right to life.

Within widespread and comprehensive remarks, panelists in both sessions addressed three divisive prohibitions – on the threat of use, transit, and testing – and discussed options for verification and elimination.

Threat of use

Mian expressed support for the prohibition of the threat of use of nuclear weapons, explaining that the 1996 International Court of Justice (ICJ) advisory opinion on the legality of nuclear weapons did not outlaw the threat of use. Burroughs argued that if the use of nuclear weapons is illegal under international humanitarian law, the threat of use should be illegal too.

Transit

Acheson suggested that an international prohibition on the transit of nuclear weapons could be modeled after similar existing national legislation in New Zealand, Austria and the Philippines. Burroughs also supported a ban on transit, emphasizing that this treaty has the capacity to set a legal precedent for the future of nuclear disarmament, and thus prohibitions must be comprehensive.

Testing

Mukhatzhanova endorsed a ban of testing, as long as support for the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) is also expressed. She suggested considering the Central Asian Nuclear Weapon Free Zone as a model for nuclear weapon testing prohibitions. Maresca, on the other hand, stated that if prohibitions included development, there would be no need to include testing as a separate prohibition.

Verification and elimination

Mukhatzhanova provided three detailed options for disarmament verification with the accession of nuclear weapons states to the treaty in her remarks. Her first option, which she called "South Africa Plus" would require all states parties to declare they do not have nuclear weapons on their terrority, thereby requiring nuclear weapons states to eliminate their arsenals before acceding to the treaty. Another approach would be to have nuclear weapons states attach a clear elimination protocol upon signing. A third option would be the least specific, allowing the process of elimination of nuclear weapons to be subject to negotiation upon accession of nuclear weapons states.

Acheson acknowledged the emerging debate among states on whether nuclear prohibition verification should rely on existing verification mechanisms or create new verification instruments and asserted that new verification standards will be necessary once nuclear weapons states join the treaty and begin to eliminate their arsenals.

Tomorrow’s sessions will discuss both institutional arrangements and the intercessional period between the first week of negotiations and the second round beginning June 15.

Day 3—Prohibitions and Positive Obligations

March 29, 2017

The third day of negotiations on a treaty banning nuclear weapons continued statements on the treaty’s preamble and launched into a debate on the treaty’s core provisions.

States and civil society, including representatives from the International Committee of the Red Cross, Western States Legal Foundation, Parliamentarians for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament, International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War and the African Council of Religious Leaders, provided statements on the preamble of the treaty in the morning session.

The session then turned to discussion of the second topic, core prohibitions. The bulk of these interventions focused on prohibitions, but states also covered positive obligations and verification measures to be included in the operative clauses of the treaty.

The session then turned to discussion of the second topic, core prohibitions. The bulk of these interventions focused on prohibitions, but states also covered positive obligations and verification measures to be included in the operative clauses of the treaty.

Prohibitions

Most states agreed on a set of core prohibitions on nuclear weapons including: use; possession; acquisition; stockpiling; transfer, and deployment. Many states added that these prohibitions should not inhibit the research and development of peaceful nuclear energy.

However, states were divided on the inclusion of several other prohibitions, including threat of use, testing, and transit of nuclear weapons.

Threat of use

Several states argued that the threat of use of nuclear weapons should be prohibited in order to delegitimize the theory of deterrence and use of nuclear weapons in security doctrines. Austria advanced that Article 2.4 of the UN Charter already prohibits the threat of use of force, and including the threat of use of nuclear weapons in the nuclear prohibition treaty would be redundant.

Testing

Indonesia and Brazil were among several states to include the prohibition of nuclear testing in their list of prohibitions. Others countered that banning testing in the nuclear prohibition treaty is unnecessary, considering that the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) already prohibits nuclear explosive testing.

Transit

Although many states recommended prohibiting the transit of nuclear weapons, a few, including Malaysia, expressed skepticism about the feasibility of enforcement of this prohibition.

Positive obligations

Antigua and Barbados, speaking on behalf of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), were among many states to call for an obligation in the treaty to provide assistance to victims of nuclear weapon use and testing. Vietnam, among others, called for the treaty to obligate states parties to address the environmental damage of nuclear weapons.

Verification

States underlined the importance of including strict verification measures to enforce both prohibitions and positive obligations.

Several states recommended modeling verification measures on those in previous prohibition treaties, including nuclear weapons free zones and the Biological and Chemical Weapons Conventions. Others suggested relying on existing verification bodies, including the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to help verify treaty provisions.

Sweden remarked that a provision requiring states parties to enter into legally binding commitments with the IAEA similar to the Additional Protocol would be “a cost effective and nonduplicative form of verification.” Sweden also proposed pursuing more comprehensive verification measures if and when nuclear weapons states join the treaty.

The afternoon session concluded with statements from several civil society organizations. Thursday’s sessions will feature open discussion on both the preamble and main provisions of the treaty.

Notable statements:

Day 2—Preparing the Preamble

March 28, 2017

The second day of negotiations on a legal instrument prohibiting nuclear weapons began with the remaining high-level opening statements, continued with the chilling story of a Hiroshima bomb survivor and concluded with the discussion of elements to be included in the preamble of the treaty.

Continued high-level statements

Although nuclear weapons states continued to boycott the negotiations, participating non-nuclear weapons states referenced them repeatedly throughout the opening statements.

Although nuclear weapons states continued to boycott the negotiations, participating non-nuclear weapons states referenced them repeatedly throughout the opening statements.

Participating delegations chastised nuclear weapons states for both their absence at the conference and the lack of progress toward meeting their NPT-related disarmament commitments in the years leading up to the conference.

Brazil, for example, complained that nuclear weapons states considered that “nuclear disarmament obligations… are voluntary,” and the Philippines, among others, noted that the Conference on Disarmament has not adopted a program of work in 21 years.

Participating states also discussed nuclear weapons states in a more positive light, often calling for inclusivity in the final treaty document and inviting states not present at the negotiations to join in at the second session in June and July or to sign the new treaty at a later date.

Following high-level statements by UN member states, Setsuko Thurlow, a survivor of the bombing of Hiroshima, told her first-person account of the atomic bombing of the city and people of Hiroshima.

“I want you to feel the presence of not only the future generations, who will benefit from your negotiations to ban nuclear weapons, but to also feel a cloud of witnesses from Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” Thurlow said.

Topic 1: Preamble (principles and objectives)

Most states suggested that both the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons use and existing relevant disarmament and nonproliferation legal instruments should feature prominently in the preamble.

Ireland suggested succinctly that the preamble should “set the treaty in human and legal context.”

Humanitarian consequences

Almost all states agreed that the catastrophic consequences of nuclear weapons use should be included in the preamble. Austria even suggested this should be the guiding principle of the treaty. The Netherlands, however, did not mention the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons in its statement.

International law

The vast majority of states recommended that the preamble recognize existing legal measures prohibiting nuclear weapons, such as international humanitarian law, the UN Charter, the 1996 International Court of Justice (ICJ) advisory opinion and the first resolution adopted by the United Nations in 1946 calling for a commission to make proposals for “the elimination from national armaments of atomic weapons and of all other major weapons adaptable to mass destruction.”

Most other states, including the Netherlands, suggested the preamble note that the treaty builds on, and does not contradict, existing nonproliferation instruments, such as the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (specifically Article VI), the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), and nuclear weapons free zones.

Other elements of the preamble

Some states suggested additional preamble components including: the gendered impact of nuclear weapons; resource reallocation from nuclear weapons to peaceful purposes; the contribution of civil society to disarmament; the suffering of victims; the need for further concrete disarmament steps; the universality and nondiscrimination of the treaty; the elimination of nuclear weapons from security doctrines; and the right of states to peaceful nuclear energy.

The negotiations will continue at 10 a.m. Wednesday, March 29 with a continued discussion on principles and objectives of the preamble.

Five notable statements of the day

- Liechtenstein

- The Republic of the Marshall Islands

- Ireland

- Switzerland

- The Netherlands

Day 1—Beginning to Ban the Bomb

March 27, 2017

The first day of negotiations on a treaty banning nuclear weapons started with a protest.

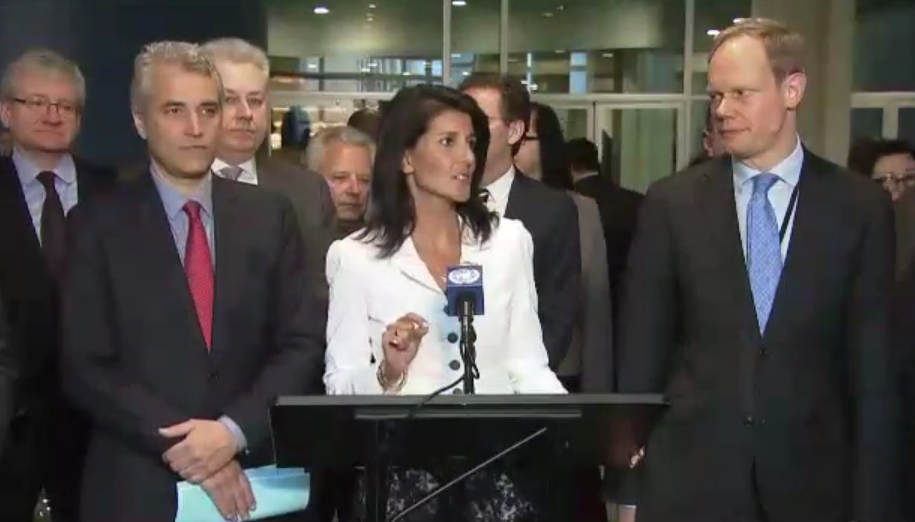

The United States ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley stood outside of the General Assembly at the opening of negotiations alongside the British and French ambassadors to the UN to explain why the United States and almost 40 other states would boycott the talks.

The United States ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley stood outside of the General Assembly at the opening of negotiations alongside the British and French ambassadors to the UN to explain why the United States and almost 40 other states would boycott the talks.

Haley claimed that she would like to see a world free of nuclear weapons, but didn’t consider the talks to be a realistic means to achieve that end.

Meanwhile, inside the General Assembly, Ambassador Elayne Whyte Gomez of Costa Rica, president of the conference, kicked off the opening session, expressing hope that a draft text on a new “legally-binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons, leading toward their total elimination” would be prepared by the spring.

The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, a civil society organization attending the negotiations, counted 115 states present at the opening session.

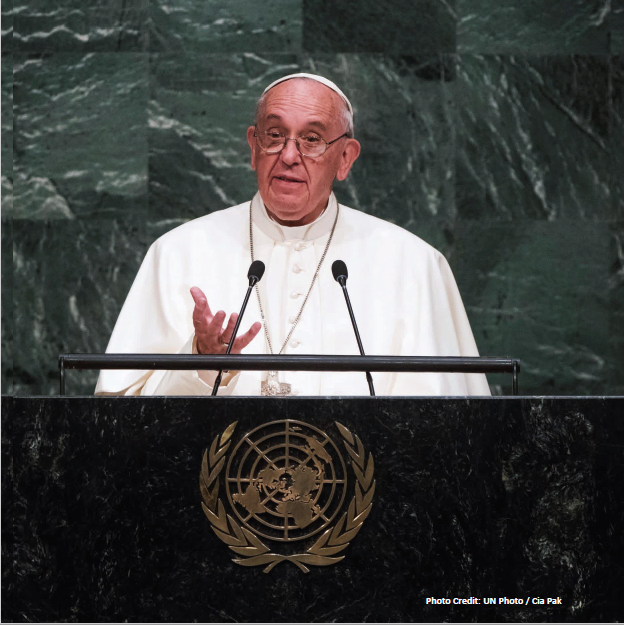

Notable individuals, including Peter Maurer of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Pope Francis, and Toshiki Fujimori, a Hiroshima bomb survivor, provided statements in support of the ban treaty before UN member states delivered their opening statements.

Of the UN member states participating in the negotiation, Ireland’s and Austria’s statements were among the strongest in support of the ban treaty, while Japan’s was the most critical.

Ambassador Nobushige Takamazawa of Japan announced that Japan would not participate further in ban treaty negotiations expressing support instead for what he called concrete, practical measures, like negotiating a fissile material cutoff treaty (FMCT) and increasing nuclear transparency through the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) review conference process.

Other high level statements focused on three main themes; the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons, that a treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons would complement the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and suggestions about specific core prohibitions to be included in the ban treaty.

Humanitarian impact: Almost all states referenced the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of nuclear use. The ambassador from Colombia quoted Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s 1986 speech, “The Cataclysm of Damocles,” to illustrate the environmental impact of a nuclear strike. Representatives from both Peru and El Salvador were among many to call the use and threat of use of nuclear weapons “a crime against humanity.”

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty: Many nuclear ban treaty supporters, including Indonesia, argued that the nuclear weapons ban treaty would strengthen and not weaken existing legal instruments, especially the NPT.

Egypt, among others, claimed a nuclear weapons ban could help to implement Article VI of the NPT, which obliges all NPT states parties to support and pursue effective measures on nuclear disarmament. The Philippines, Cuba, and others also expressed support for all three pillars of the NPT, including the right to peaceful use of nuclear energy.

Core prohibitions: Several states, including Mexico, Antigua and Barbados on behalf of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), Ecuador, and Cuba provided specific lists of prohibitions to be included in the nuclear ban treaty, including the prohibition of deployment, assistance in development, financing, transfer, import, stockpiling, threat of use and use of nuclear weapons. Cuba’s list of prohibitions was perhaps the most extensive and included banning design and research for modernization of nuclear weapons and all nuclear tests, including sub-critical tests.

Negotiations on a treaty to ban nuclear weapons continue tomorrow, Tuesday, March 28 at 10 a.m. EST in New York and will be broadcast on the UN website.