"I find hope in the work of long-established groups such as the Arms Control Association...[and] I find hope in younger anti-nuclear activists and the movement around the world to formally ban the bomb."

Seeking the Bomb: Strategies of Nuclear Proliferation

July/August 2022

Nuclear Proliferation Is Nuclear Strategy

Nuclear Proliferation Is Nuclear Strategy

Seeking the Bomb: Strategies of Nuclear Proliferation

Vipin Narang

Princeton University Press

2022

381 pages

Reviewed by Douglas B. Shaw

Vipin Narang’s Seeking the Bomb: Strategies of Nuclear Proliferation is a triumph. It offers important actionable recommendations for nuclear proliferation policy. It presents discoveries that significantly advance scholarly understanding of nuclear proliferation. It is also an accessible, authoritative introduction to nuclear proliferation for leaders, undergraduate and graduate students, and the public.

The book is a clear, essential guide to nuclear proliferation policy. It identifies two key policy levers for preventing nuclear proliferation. The first is to delay nuclear weapons programs to buy time for political change. The second is to fracture the domestic political consensus for nuclear weapons acquisition in states of nuclear proliferation concern. These recommendations apply the key finding of nuclear proliferation scholarship over the last generation: nothing stops a state determined to acquire nuclear weapons.

Although Narang is appropriately skeptical of the possibility of preventing a state determined to acquire nuclear weapons from doing so forever, he challenges the common assumption that most nuclear proliferators sprint to the bomb by predicting the future prevalence of hidden nuclear weapons programs. This unexpected finding suggests that improving capabilities for finding hidden programs should be a policy priority.

Narang cites the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), among China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States, the European Union, and Iran, as a model policy application of his theory. The JCPOA aligned with his research findings by delaying Iran’s nuclear program and reinforcing fractures in the Iranian domestic political consensus on nuclear weapons acquisition. Describing the JCPOA’s success in reversing Iran’s progress toward the bomb, the author observed that “the biggest threat to the success of the JCPOA proved to be…domestic politics in the United States,” thus highlighting the essential problem looming over all future efforts to prevent nuclear proliferation.

Cracking a Nuclear Puzzle

Theoretically, Narang cracks a methodological puzzle that has bedeviled nuclear proliferation scholarship for more than a decade: how should states’ progress toward acquiring nuclear weapons be measured? In his chapter in Forecasting Nuclear Proliferation in the 21st Century, Scott Sagan clarified this puzzle in 2010 as “how quickly could individual governments…develop a nuclear weapon if they chose to do so”? Examining various coding schemes and the complexities of nuclear fuel-cycle technology choices, Sagan concluded that “any general measure of ‘nuclear latency’ is likely to be a chimera” and recommended an expansive “multi-disciplinary research agenda” incorporating several complex, interrelated political, economic, and technical considerations.

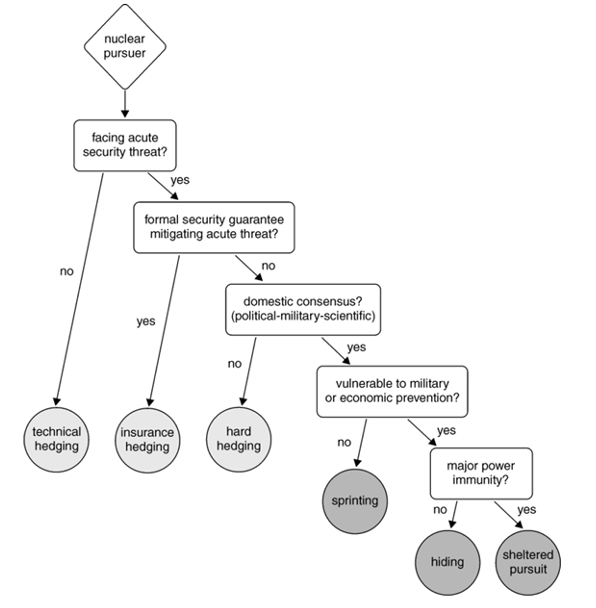

By asking a novel question, how do states pursue nuclear weapons instead of whether states will or how long it will take, Narang sidesteps what Sagan calls the “quixotic goal” of measuring nuclear latency directly. Instead, Narang offers a comprehensive, mutually exclusive typology of six nuclear proliferation strategies. Three are “hedging” strategies among states that are retaining an option for future nuclear weapons acquisition but have not yet decided to build a nuclear weapon, and three are strategies of active nuclear weapons pursuit.

Narang connects these six strategies through a handful of variables in sequence. The first variable is whether the state faces an acute security threat. If not, Narang predicts it will engage in a strategy of “technical hedging,” that is, developing relevant technologies to hold an option for nuclear weapons development “explicitly not now, but implicitly not never.” If the state does face an acute security threat, the second variable comes into play: can the state mitigate its acute security threat by a formal security guarantee from a great power? If yes, he predicts the state will adopt a strategy of “insurance hedging [which is to say] explicitly not now, but explicitly in the future if X happens.” That means that a state will take steps to reduce the time it will take to acquire nuclear weapons if triggered by a change to its security situation (fig.1).

Narang illustrates insurance hedging vividly with the case of Japan, citing the explicit communication by Japan and the acknowledgment by the United States that “Japan would go nuclear without an unequivocal American security guarantee.” He describes Japan’s conscious use of a civilian nuclear energy program as a “latent deterrent,” a term used by Satoshi Morimoto while he was the Japanese defense minister. Narang observes that “any time there has been a perturbation in the external security environment…Japanese leaders—across all parties—have not so subtly publicly mentioned the threat to go nuclear” and each time “the United States has obliged in reaffirming Japan’s request for an ‘unshakable nuclear umbrella.’” He raises an intriguing possibility that Japanese threats of nuclear proliferation could be constrained not just by U.S. security assurances but by “a lack of domestic consensus,” which has never been demonstrated.

Narang illustrates insurance hedging vividly with the case of Japan, citing the explicit communication by Japan and the acknowledgment by the United States that “Japan would go nuclear without an unequivocal American security guarantee.” He describes Japan’s conscious use of a civilian nuclear energy program as a “latent deterrent,” a term used by Satoshi Morimoto while he was the Japanese defense minister. Narang observes that “any time there has been a perturbation in the external security environment…Japanese leaders—across all parties—have not so subtly publicly mentioned the threat to go nuclear” and each time “the United States has obliged in reaffirming Japan’s request for an ‘unshakable nuclear umbrella.’” He raises an intriguing possibility that Japanese threats of nuclear proliferation could be constrained not just by U.S. security assurances but by “a lack of domestic consensus,” which has never been demonstrated.

Without a formal security guarantee from a great power, the third variable becomes decisive: does the state have a domestic political consensus in support of nuclear weapons acquisition? If not, Narang predicts the state will adopt a strategy of “hard hedging,” which is distinguished from insurance hedging primarily by the absence of any condition for deciding to pursue nuclear weapons beyond building domestic political consensus. Hard-hedgers stand on the threshold of the nuclear proliferation decision, and their position toward nuclear weapons is “explicitly not now, but explicitly not never.”

If a state does have a domestic political consensus in favor of pursuing nuclear weapons, it moves on from hedging to one of three strategies of active pursuit of nuclear weapons. Some states “sprint” toward nuclear weapons because they are large or advanced enough to be invulnerable to military or economic efforts to prevent their success. The United States and Russia were sprinters. Narang observes that most nuclear proliferation literature assumes that future proliferators will be sprinters, but his theory predicts that this is unlikely because most remaining potential proliferators are susceptible to prevention. If a state is vulnerable in this way but “the proliferator has found itself useful to a major power for other domestic or geopolitical reasons that override nonproliferation concerns,” Narang predicts it will adopt a strategy of “sheltered pursuit.” For example, he observes that following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the United States prioritized confronting the Soviet Union over preventing nuclear proliferation by Pakistan and thus sheltered Pakistan’s pursuit of nuclear weapons. Narang predicts that most states will be susceptible to prevention and therefore proceed to acquire nuclear weapons through a hidden program. He concludes that many future nuclear weapons aspirants will be “hiders,” concealing their pursuit of nuclear weapons and expecting “a violent fate if discovered.”

Narang’s book is an outstanding educational tool for students and the public. It offers a broad foundation of knowledge with a clear theoretical frame explicated through concise, authoritative case studies. He digs into the question of weapons-usable nuclear materials in new and enlightening ways.

Common Constraints of Nuclear Research

Alongside dramatic advances in understanding nuclear proliferation, Seeking the Bomb reflects the many persistent constraints on the study of nuclear proliferation. The book accepts as correct the view that nuclear weapons are “the one capability that can essentially indefinitely insure their regime or country,” and thus the book excludes perspectives that may be vital for human survival. It treats the danger of a nuclear war resulting from accident, miscalculation, or blunder as the summation of the responsibility of individual nuclear-armed states rather than as the product of an incomplete, flawed, and fragile global architecture of nuclear deterrence. Assuming that the prevailing understanding of nuclear weapons is correct reinforces this understanding without evidence.

The scale of damage that nuclear war threatens to impose on human civilization and the planetary environment are outside the book’s scope, as are the shocking human security costs of nuclear weapons programs, as explained by Togzhan Kassenova and others. Focusing almost exclusively on states as the relatively timeless objects of interest in shaping world politics risks turning a blind eye to the potential future collapse of nuclear-armed states, which in the case of the Soviet Union posed dramatic dangers for international security and nuclear proliferation.

Narang’s proliferation strategy theory describes approaches to statecraft and military policy without deep consideration of the role of science and industry. Careful observation of the scientific and industrial dimensions of nuclear technology dispels notions of a smooth, continuous technological line separating “bad” nuclear proliferation activities from “good” peaceful activities. The complex reality of a global nuclear energy industry that produces and, in some cases, separates large quantities of plutonium has consequences for nuclear proliferation risk. Similarly, future advances in nuclear fuel-cycle technologies could make it easier to hide the pursuit of nuclear weapons, especially if technology for detecting these activities does not keep pace.

Narang’s proliferation strategy theory describes approaches to statecraft and military policy without deep consideration of the role of science and industry. Careful observation of the scientific and industrial dimensions of nuclear technology dispels notions of a smooth, continuous technological line separating “bad” nuclear proliferation activities from “good” peaceful activities. The complex reality of a global nuclear energy industry that produces and, in some cases, separates large quantities of plutonium has consequences for nuclear proliferation risk. Similarly, future advances in nuclear fuel-cycle technologies could make it easier to hide the pursuit of nuclear weapons, especially if technology for detecting these activities does not keep pace.

Narang’s case selection is impressive within the common practice of examining states that have explored the possibility of acquiring nuclear weapons. This is understandable in a book that responds to the expert community’s continuous demand to explain the most difficult cases. By excluding states that have not considered nuclear proliferation seriously, Narang accepts the common assumption that acute security threats are the cause of such consideration. Although this assumption that security threats drive nuclear proliferation is plausible, rigorous tests of other common assumptions are what distinguish this book as outstanding political science and a validation of the idea that careful observation can reveal what casual observation does not. Because he selects cases without variance to whether nuclear proliferation is considered, Narang’s theory tells us nothing about the behavior of the majority of the world’s states, which have forsaken nuclear weapons and are non-nuclear weapon states-parties to the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) in good standing. As a result, it tells us nothing about how or why states that never explored nuclear weapons acquisition made that decision, even when they have invested substantially in developing nuclear technology.

Narang gives surprisingly little attention to the 1994 Agreed Framework between North Korea and the United States, which is especially noticeable in the context of his enthusiastic support for the JCPOA. While it lasted, the framework posed a verified obstacle to North Korean use of the Yongbyon reactor to produce plutonium for nuclear weapons. North Korea’s pursuit of a uranium pathway to nuclear weapons while the framework was in force, the U.S. delay in fulfilling its commitments, and the framework’s eventual collapse are additional reasons to compare it rigorously with the JCPOA. The two deals share characteristics as coerced, bespoke, highly intrusive, one-sided nonproliferation verification schemes targeting states that the other parties to the deals do not trust. These are ample reasons to compare them carefully.

A Path to Future Research

The book opens pathways to potentially transformational future research. Narang’s identification of multiple nuclear strategies prior to nuclear weaponization suggests the possibility of identifying additional nuclear strategies to describe the behavior of states that have not considered nuclear weapons acquisition and those who rely heavily on large nuclear arsenals. One can imagine moving further up and to the left on Narang’s research chart to describe the behavior of states without nuclear weapons, states that act to promote restraint internationally, and states that mediate between nuclear-weapon states and others. Such a comprehensive typology of the nuclear strategy of all states would create an alternative, not only to the technical measurement of nuclear proliferation latency as Sagan defines it, but also to the challenge of measuring “universal latency” that authors Raymond Juzaitis and John McLaughlin identified in 2007 as essential to progress toward nuclear disarmament. Those authors called for an “explicit and nationally supported program of technology development to prepare for the eventuality of getting close to zero [nuclear weapons] and therefore needing greater transparency than current techniques are likely to provide.” Such a national innovation ecosystem is required equally and independently for the important national security objectives of reducing the risk of nuclear war, preparing to fight nuclear-armed adversaries, preventing nuclear proliferation, and implementing possible nuclear disarmament.

These challenges remain daunting conceptually, organizationally, and technologically. By offering policy solutions to nuclear proliferation that do not depend on the technical measurement of nuclear latency, Narang points the way to advancing these objectives in ways that could guide innovation in detection, monitoring, and verification technology. Identifying nuclear strategies further away from weaponization could create a comprehensive, mutually exclusive typology of all possible nuclear strategies. Such a map could embrace the horizontal and vertical nuclear proliferation choices of all states and describe nuclear arsenals of all sizes. In “A World Without Nuclear Weapons” in 2009, Thomas Schelling imagined a “schedule showing how many weapons (of what yield) a government could mobilize on what time schedule” to which tailored standards of verification inspections could be applied for all states. Implementation of Schelling’s vision was blocked at the time by the challenge of measuring nuclear proliferation latency. Narang’s breakthrough research could reinvigorate the disarmament agenda by creating a comprehensive typology of observable nuclear weapons behavior for all states.

Preventing the spread of nuclear weapons to more states is often considered to be a background condition for preventing war through nuclear deterrence. The established nuclear- weapon states will never reduce their arsenals if they fear the nuclear weapons club will grow. By creating a context for recognizing nuclear proliferation strategies as ways states use nuclear weapons to pursue their security, Narang opens the door to a much wider understanding of nuclear coercion as a global phenomenon in which many states participate. This expanded view of nuclear strategy will be necessary for responding to the dangers that nuclear weapons technology will pose far into humanity’s future.

Douglas B. Shaw consults on nuclear weapons policy research and education and is a research professor of international affairs at The George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs.