January/February 2025

By Walter Slocombe

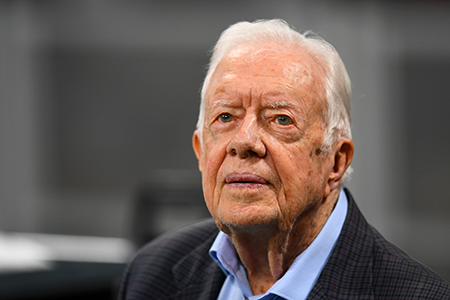

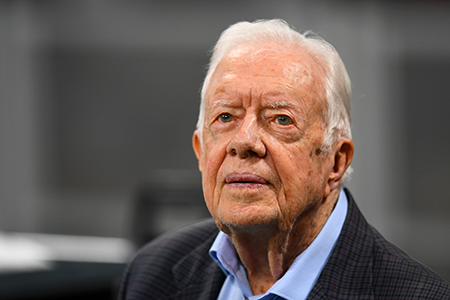

Observers as different as Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski agreed that President Jimmy Carter had a deep personal commitment to arms control as a means of reducing the risk of nuclear war. That commitment was based on Carter’s moral principles and religious faith, his experience as an officer in the nuclear navy, and his understanding of the horror of nuclear war. He hoped for the ultimate abolition of nuclear weapons, but accepted that arms control was a necessary stage toward that end. Carter, who died December 29 at the age of 100, repeatedly said that arms control was his top priority as president.

The Carter administration launched efforts on multiple fronts: nuclear proliferation, nuclear weapons testing, arms sales, restraint on technological advances, nuclear-weapon-free zones, pullbacks of some U.S. nuclear deployments around the world, and restrictions on nations from outside the region deploying their military forces to new regions, such as the Indian Ocean. These efforts, including Carter’s attempts to negotiate an expanded ban on nuclear testing and to block a neutron bomb, had various degrees of success and controversy, but his main focus was endeavoring to impose limits on strategic forces, and that was the arms control issue in which he was most involved. Although the treaty that he negotiated under the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) was not ratified, it was, from the perspective of priority and personal involvement, his biggest national security success apart from the Egypt-Israel peace agreement.

From the moment Carter assumed office in 1977, he hoped to take dramatic steps beyond the initial 1972 agreements on offensive nuclear weapons and missile defenses achieved by President Richard Nixon and beyond the tentative arrangements that his immediate predecessor, President Gerald Ford, and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had worked out with the Soviet Union at the Vladivostok arms control summit in 1974. Carter was convinced that, for all their other faults, Brezhnev and the rest of the Soviet leadership recognized the essential need to confront the nuclear danger.

Accordingly, Carter believed that a comprehensive, far-reaching U.S. initiative at the start of his administration would appeal to the Kremlin and instructed his new team to develop a proposal to achieve that end. He clearly hoped that the Soviets were open to dramatic action. After all, Kissinger, the architect of the Nixon-Ford arms control agenda, had been briefed on the general thrust of Carter’s initiative and, with characteristic ambiguity, had told the president that the Soviets might agree.

Within a few weeks, Carter had settled on offering the Soviet leaders a choice. His much-preferred option sought agreement on significant cuts below the level that had been decided tentatively at Vladivostok and on expansion of the scope of the limitations to include constraints on heavy missiles as the weapons having the most dangerous potential for attempting a disarming preemptive strike. He also offered the alternative of a quick agreement along the lines of the U.S. position at Vladivostok.

When Secretary of State Cyrus Vance presented these proposals in Moscow in May 1977, however, the Soviets bluntly rejected both options. The deep cuts apparently were too ambitious, and the limited step was viewed as repudiating a consensus that the Soviets claimed was settled definitively at Vladivostok. Carter decided not to permit his negotiators to advance a fallback position that he had approved for use in Moscow if the Soviets had proved ready to engage immediately in serious negotiations.

Afterward, Carter was widely criticized for thinking that the cautious and sclerotic Soviet leadership would jump at a chance for rapid steps forward. The media, well-organized political opponents of the arms control process, and some experts proclaimed the imperilment, if not the end, of negotiations on strategic nuclear weapons. In fact, in the face of overwrought media and opposition scorn for his substantive proposals and his supposed naivete, inexperience, and overambition, Carter quickly accepted that an agreement would require more time and painstaking negotiation.

Within a few weeks, he had the process back on track. Complex negotiations over many months thereafter were complicated by the fact that although his senior advisers accepted and supported the broad goal of a SALT II agreement, Vance and Brzezinski had distinctly different views on where the agreement fit in the overall U.S. relationship with the Soviet Union. This concept came to be called “linkage.” Vance viewed an agreement as being as much in U.S. interests as it was in Soviet interests—useful not only on its own terms but as an essential building block for a general improvement in U.S.-Soviet relations. Brzezinski, while genuinely supporting pursuit of an agreement, believed that the Soviet Union needed a deal more than the United States did and therefore the United States had leverage for conditioning progress on SALT II on moderation of Soviet conduct more generally.

The linkage debate between the contrasting arms control views of the two senior advisers was exacerbated further by their differences on the normalization of relations with China, which were moving toward implementation just as the SALT II negotiations neared culmination. Although both men supported normalization in principle, Brzezinski saw it as a means to present the Soviet Union with the specter of a de facto U.S.-Chinese alliance. Vance, by contrast, feared that taking that major diplomatic step toward China with SALT II still unresolved would reduce the Soviet willingness to negotiate.

In this regard, Carter was wiser than his advisers. Rather than adopt either view, he recognized that both goals, an agreement on SALT II and prompt normalization with China, would serve U.S. security. He rightly judged that Soviet interest in calming the bilateral strategic nuclear relationship would limit the Kremlin’s reaction to normalization with China. Carter declined to attempt to use two military projects that he had already decided to disapprove, the B-1 bomber and the neutron bomb, as bargaining chips, but he ensured that the United States responded to Soviet actions that posed a danger to its national security interests. For this reason, he chose to conduct the SALT II negotiations independently of other issues while taking steps to respond to Soviet challenges and enhance U.S. military capabilities. These steps included increasing the national defense budget and seeking, with some success, to persuade allies to do the same.

The budget increases funded such defense innovations as the development of stealth technology and the acquisition of other new conventional systems, such as stealth aircraft, highly accurate ground ordnance, and sea- and air-launched cruise missiles that formed the backbone of U.S. capabilities for a generation. Carter also implemented an ambitious program of modernization of each element of the U.S. deterrent force, including cruise missiles for bombers, the new D-5 missile for submarines, and a new land-based MX missile to be based in such a way as to be invulnerable to preemptive attack.

He rejected the idea of adopting a no-first-use of nuclear weapons policy as weakening deterrence and launched a program to deploy ground-launched nuclear missiles in Europe as a response to Soviet deployment of the new SS-20 missile, which had a range below the SALT threshold but was sufficient to reach most of Europe. It is a measure of Carter’s understanding of his unique responsibility as commander in chief of the U.S. nuclear arsenal that he oversaw a reshaping of the basic principles guiding nuclear doctrine and planning and gave unprecedented attention to the operational aspects of procedures for deciding on and, if necessary, shaping any actual use of nuclear weapons.

Domestically and internationally, Carter’s arms control efforts faced political obstacles as formidable as the Soviet negotiators. The Cold War context was hardly conducive to cooperation with the Soviet Union. The U.S. failures in Vietnam raised questions among allies about U.S. will, judgment, reliability, and capability. Carter’s term coincided with the era of Soviet proxy campaigns in places such as Angola, Nicaragua, Somalia, and Yemen. It did not help that these adventures were often executed on behalf of Moscow by Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

Moreover, since the mid-1960s, the Soviets had carried out a rapid catch-up strategic force expansion that, by some limited criteria, exceeded U.S. levels and with various degrees of plausibility could be portrayed as threatening the survivability of U.S. land-based forces. These factors not only made bilateral talks difficult, but they also fueled doubt among the U.S. public about agreeing with Moscow about anything, including arms control.

At home, Carter faced criticism over the terms and details of negotiations with the Soviets and often an outright denial of the basic value of arms control generally and the SALT II negotiations specifically. U.S. Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson (D-Wash.) and longtime prominent Democratic defense figure Paul Nitze, perhaps the most vocal and well informed of the critics, had backers in Congress, the media, think tanks, and some elements of the defense industry and the retired military officer corps. Although some Republicans supported Carter’s efforts, the Republican Party institutionally had an interest in portraying the Democratic administration as weak and incompetent. On Carter’s own side of the political divide, several important Democratic members of Congress, some peace activists, and national security experts seemed willing to regard any plausibly negotiable deal as inadequate while others were lukewarm at best. Moreover, some Democratic senators ostentatiously demonstrated their independence from an unpopular president with exaggerated skepticism about elements of his centerpiece security agenda.

Faced with this difficult environment, Carter and his team recognized that getting the SALT II treaty ratified by the Senate would be as great a challenge as negotiating it with the Soviets. An absolutely necessary condition for Senate approval of a treaty, although by no means a sufficient one, was its validation by senior military leadership. To this end, Secretary of Defense Harold Brown, for whom I lead the SALT II staff in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, and Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman General David Jones managed to avoid getting entangled in the Vance-Brzezinski linkage debate. Their priority for substantive and ratification reasons was negotiating an agreement that served to reduce nuclear risks and protect Department of Defense equities, in the sense of not foreclosing potentially important U.S. strategic programs and of ensuring that the Joint Chiefs of Staff would unequivocally endorse whatever emerged from the negotiations. The Joint Chiefs of Staff duly endorsed the treaty as “modest but useful.” Some wag observed that not much in Washington exhibits both those characteristics.

Carter may have been overly optimistic about rapidly resolving all the details, but what was ultimately agreed, in addition to defining treaty terms and obligations with unprecedented precision, accomplished much of what was in his original proposal. These included top-line aggregate numbers that were lower than the ones discussed at Vladivostok, sublimits on heavy missiles and missiles with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles, a range of limits on new missiles and on modernization, meaningful controls on cruise missiles while preserving critical U.S. programs, and a prohibition on concealment measures that impede verification, such as encryption of missile test data. Carter oversaw the arcane negotiation of technical details and often had to resolve differences within the administration. His intense personal participation culminated when, in the final day before signing the treaty, he secured a personal assurance from Brezhnev on the production rate for the Soviet Backfire bomber, whose status had been in contention from the beginning of the process at Vladivostok.

Even without linkage and with relatively early agreement on numerical limits, the negotiations were protracted. Final agreement came only in June 1979, worryingly close to the 1980 presidential election. The administration, with Carter in the lead, had sought to keep senators informed of the status of the talks as a way to lay the foundation for ratification. Prolonged Senate hearings addressed a wide range of issues, from the obscure to the fundamental and from the serious to the pretextual.

Although the opposition to ratification was relentless and the good faith concerns of many senators required painstaking explanation, Carter was ready by late 1979 to bring the treaty up for a Senate vote because he was cautiously optimistic that he had the necessary 67 votes. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979, however, destroyed any possibility of ratification on that timetable. Iran’s seizure of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and the taking of 52 American hostages destroyed whatever prospect there may have been to restart the ratification campaign during the last year of Carter’s term. His defeat by Ronald Reagan denied him a second term and the opportunity to move toward a SALT III agreement with even more far-reaching constraints.

It was a bitter disappointment for Carter that the SALT II treaty did not come into legal effect, but that did not mean the failure of Carter’s effort. The Soviet regime and the Reagan administration complied with most SALT II provisions. The framework of numerical and qualitative limitations that the treaty established provided the foundation for future agreements over the next several decades. Carter’s dedicated labor for arms control is a proud and consequential component of his legacy.

Walter Slocombe led the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) task force in the Office of the U.S. Secretary of Defense during the SALT II negotiations and later was undersecretary of defense for policy.

President-elect Donald Trump is retaking office at an inflection point in Iranian nuclear policy. After long denying any interest in nuclear weapons, Iranian officials are now publicly debating the security value of a nuclear deterrent and threatening to pursue nuclear weapons if attacked.

President-elect Donald Trump is retaking office at an inflection point in Iranian nuclear policy. After long denying any interest in nuclear weapons, Iranian officials are now publicly debating the security value of a nuclear deterrent and threatening to pursue nuclear weapons if attacked.