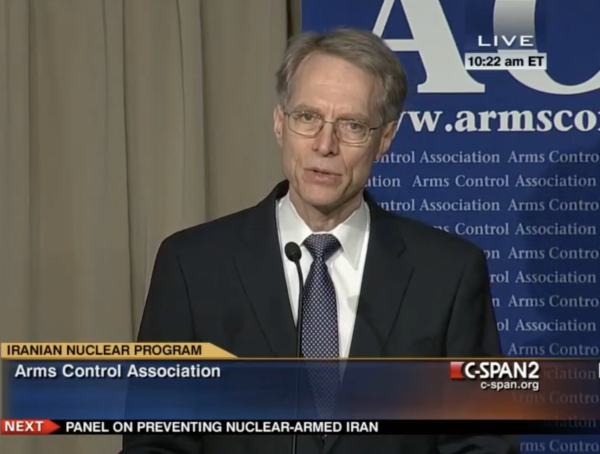

Last autumn, Greg Thielmann stepped down from the board of directors of the Arms Control Association (ACA) after nearly a decade of counsel and support. This was Thielmann’s fourth retirement, after careers as a foreign service officer with the U.S. Department of State, as a Congressional staff member, and as a member of the staff at ACA, where he served as senior fellow from 2010-2016.

Thielmann attained a public profile in 2003 following the U.S. invasion of Iraq, when he accused the Bush administration of misconstruing intelligence assessments to justify the war. Thielmann had served in the State Department’s Intelligence and Research Bureau as an arms control and nonproliferation expert in the lead-up to the invasion.

Thielmann sat down in October 2025 with Lipi Shetty, ACA’s Herbert Scoville Peace Fellow, to discuss his career and his concerns regarding current U.S. nonproliferation policy vis-a-vis Iran.

This interview has been edited for clarity and flow.

Lipi Shetty: Can you tell us about your career trajectory, and what drew you to intelligence work at the State Department?

Greg Thielmann: How I got into the State Department’s Intelligence [and Research] Bureau (INR) was related to my assignment to Moscow in 1988 to 1990. A requirement was mastering what was going on in arms control between the U.S. and the Soviet Union at that time. When I finished my tour in 1990, there were a lot of opportunities to get assignments in the Soviet Union, which was breaking up and so had new embassies all over the place. Yet a lot of those were unaccompanied tours and I was eager to get back to more sane hours and spend time with my wife and daughter at home.

[Given] the experiences I had had in Moscow, it seemed to make sense to take advantage of an opening in the Intelligence Bureau of the State Department, where we were keenly monitoring what was happening to the nuclear weapons in Ukraine and Belarus and [elsewhere] as the Soviet Union broke up. So that made it a very interesting job and an easy entry into the intelligence community.1

I had been involved prior to that in intermediate-range nuclear forces negotiations, and I had been a special assistant to Paul Nitze. So, I was very much steeped in arms control matters and U.S.-Soviet arms control negotiations before Moscow. My assignment to Moscow was more as an arms control expert rather than a Russian expert.

Lipi Shetty: What was your role in the intelligence community leading up to the Iraq War?

Greg Thielmann: My second tour [at INR] put me in charge of the intelligence office that analyzed what was going on with political-military issues, on arms control issues, around the world. And one of the hottest issues, of course, was what Saddam Hussein was doing in Iraq in the early 2000s. My office – which I thought was very well plugged in, with several people who had been working for years on the subject and were very well acquainted with the experts around the U.S. on the subject – had an interpretation of affairs which turned out to be much more accurate than that of the majority of intelligence agencies.

There are long explanations for that. But the short explanation is that following the 9-11 attacks, George W. Bush was very much interested in retaliation. He even made references to the man who tried to kill my daddy, referring to a Hussein-backed assassination attempt when former President George H.W. Bush was visiting [Kuwait].

And it was quite clear that his Vice President, Dick Cheney, and others were very keen on attacking Iraq. The weapons of mass destruction angle was more of an excuse than a real rationale. There were, at the time, a lot of different explanations for the idea of attacking Iraq. And a lot of it had to do with the reputation of Saddam Hussein – in spite of the fact that he was more or less an ally of the United States during Iran’s long war with Iraq and even given aid by [Secretary of Defense] Donald Rumsfeld, among others, who had greeted him in the Middle East.

So, there’s a long history there. But after 9-11, the American people definitely wanted revenge against the people who were guilty of attacking the United States, and in the popular mind, it was very easy for Bush to blame Saddam Hussein, even though Hussein and Al-Qaeda were mortal enemies. That was one of the things that my office was responsible for pointing out. It was so obvious that even the head of the CIA admitted that publicly and indirectly chastised the president for using [the purported connection] as an argument. But that was one of the many emotional reasons why people were eager to attack Iraq. Partly [there was] a very unsophisticated attitude that any enemy who speaks Arabic in the Middle East is somehow responsible for the 9-11 attacks.

So, there was that mood. And that meant that some of the intelligence organizations, I’m afraid to say, were overly influenced by the knowledge that the president wanted any evidence that could be used to justify an attack on Iraq.

Lipi Shetty: Would you say analysts in different parts of the intelligence community were feeling pressure from the administration? Or did they internalize the post-9-11 need for some sort of pushback?

Greg Thielmann: I think the reality is complicated. There are some agencies, like the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), which, understandably, lean toward a more alarmist interpretation of incoming intelligence. The reason is not out of perversity or a lack of dedication to the science, but rather that the consequences of underestimating potential threats come down very hard on the U.S. military, and the military will have to pay the price in blood of those underestimations. [For the DIA] the general rule of thumb is it’s better to overestimate the threat and the consequences are much less dire in that case. So, there is that sort of institutional bias of some members of the intelligence community.

Less excusable is the Central Intelligence Agency, which, I know from personal experience, at that time was exaggerating the information we had, indicating that the Iraqis were moving forward with weapons of mass destruction programs even after the successful liberation of Kuwait and the imposition of fairly strict limits on Iraqi activities. [Those limitations] should have reassured a number of people, given that we were getting a lot of detailed information. We, in fact, knew a great deal about even the individuals who were involved in Saddam’s previous nuclear weapons program.

That information was what went into our analysis, [along with the interpretations of] area experts like Joe Wilson, who had been involved early on in his career in Niger.2 Niger was allegedly providing uranium for the Iraqi program, but we now know that [this accusation] was partly analysis from Italian forgeries done, also, to satisfy the U.S. desire to have evidence. This was suspected by us [when we reached] our decision early on in 2002 that Saddam Hussein’s nuclear program was dormant.

It wasn’t moving forward rapidly; it was not out of control of the international community. That seemed obvious to us in early 2002 when we first assessed some of the reports to the contrary.

But [our analysis] apparently did not convince other agencies. Even though it convinced the specialist at the Department of Energy, who knew the uranium [technical aspects] better than most, it did not convince the senior leaders of the Energy Department not to join the overwhelming consensus that Iraq was violating all elements of the weapons of mass destruction constraints that had been imposed on it.

So, it’s kind of a sad and complicated story. But I am very proud that the State Department did what I thought was the right thing and correctly analyzed the information, regardless of whether it served the political interests of the administration or the head of the department or not. We did our job, rather than bend to the wind.3

Lipi Shetty: Could tell me a little bit more about the process for creating an intelligence report at the State Department?

Greg Thielmann: There were several different ways we would reach senior State Department officials with our information. That was the principal job of the State Department’s Intelligence Bureau: to make sure that the leaders at the State Department knew what the overall intelligence community was producing, even very sensitive stuff.

One of the ways that was done was a daily intelligence report that went to the Secretary of State. The various offices in the Intelligence Bureau [would write] up some of the incoming intelligence, some of it very sensitive, and [let] the Secretary and some of his assistants know what was happening.

Some of the information came from State Department reporting cables, which was our special contribution to the overall intelligence community. The product was understanding what was happening at the State Department and its embassies overseas, in terms of what we were learning from foreigners about intentions and behavior and so forth.

So, for example: when the overall intelligence community did a national intelligence estimate on the foreign ballistic missile threat, I represented INR in those coordination sessions to come up with the exact language in the report. In that report, a number of assumptions were made about the foreign ballistic missile threat that the U.S. would face beyond the Russian and Chinese threats that we were familiar with. It included the addition of the North Koreans and the Iranians and the Iraqis on that list.

We had no problem with the overall assumption that these countries were all potential ballistic missile countries with, potentially, nuclear weapons. But we definitely differed in the timing of the threat.

The State Department was the only bureau, the only entity in the intelligence community, that disagreed with the idea that North Korea would test an intercontinental ballistic missile type system that could threaten the United States by the end of 1999 – that is, within a few months.4 And we were right. In fact, North Korea did not conduct such a test for 17 years. That was a phenomenally inaccurate forecast by the intelligence community.

Of course, there was very little attention given to the fact that INR dissented from it in a conspicuous way, but we did. That was an early indication of an example where we got it right, and the majority got it wrong. So, we were proud of that, too.

Lipi Shetty: How are intelligence assessments from different members of the intelligence community weighed against each other? Is there more priority given to certain agencies?

Greg Thielmann: I’d say there is. I think the CIA is really on top. The CIA is supposed to be independent and not subservient to the views of any department of government.

There are problems with that assumption because the CIA, understandably, wants to be influential and often reacts to the biases of the political leadership in the White House in a way that the State Department has been more successful at resisting.

There are other agencies that have specialized functions. The NSA is communications intelligence, and, in some respect, this is considered very accurate because it’s usually collected unwittingly. That is, there’s no possibility for people to influence the espionage. It’s therefore considered quite persuasive when we get good intelligence.

But there are instances, historical instances, that we cannot forget when the NSA inadvertently played a very unfortunate role in U.S. policy decisions. I refer to the Gulf of Tonkin.5 It’s a very interesting example of how even very reliable intelligence agencies can somehow lead to enormous error that has enormous consequences.

Lipi Shetty: Do you see any parallels between the misuse of intelligence during Iraq and our current situation with Iran?

Greg Thielmann: I do see some parallels. One of the parallels, of course, is the way that a lot of the policy makers, requesting intelligence [and] making assumptions about Iran, ignore things like our activities in 1953 that fundamentally changed how the Iranians felt about the U.S. But Iran is a very tough issue. In my analysis, it was extremely important that the U.S. agreed in 2015 to the deal that we made with Iran that limited the extent and speed of their nuclear proliferation program.

I regard this as a great diplomatic triumph. And it wasn’t perfect, obviously, and maybe did not slow down the Iranians as much as we would have wanted, but it was very important, and it was achieved with five other countries and the UN Security Council. It was a great tragedy when President Trump withdrew from this agreement at a time when the Iranians were fulfilling their obligations under the agreement.

We had the situation, in my mind, very much under control in terms of Iranian nuclear proliferation. The U.S. reneging on its agreement provided a very poor example of reliability as a negotiating partner. The Iranians still complied with the agreement for a little while, but then eventually started violating some of its provisions. And I hold the U.S. responsible for that as much as the Iranians.

Now, whether the U.S. and the Israelis are justified in the murder of various Iranians involved in WMD programs: it’s an interesting ethical issue. I have my own views on that. I think it’s hard to establish those kinds of murders as being acceptable in the kind of international community that we would like to associate with.

But I clearly think it was a mistake to have this massive, U.S. strategic attack on Iran, as if the destruction of facilities is all we need to do. This “mowing the grass” alternative – perpetual war against a country like Iran [given] any indication that it’s doing something that we don’t like it to do – I think it’s a mistake. I think it will be harder for us to negotiate the kind of agreement we need as a result of our actions, which, unlike what President Trump said, did not totally obliterate Iranian capabilities. It set them back.

A country as large as Iran, and with a program as sophisticated as Iran’s, cannot be bombed out of existence, so I think we’ve made our problem worse.

Lipi Shetty: Is there anything else that you wanted to talk about?

Greg Thielmann: I will just leave you with one comment that I remember making to my staff [at INR]. I wanted them to try very hard to be accurate and prescient in their analysis. And I said, it’s also nice to be influential in your analysis. But between the two, I would rather you be accurate and prescient than influential.

I’m afraid that that’s partly the story of INR. INR was very skeptical about Vietnam in the 1960s, and I think it lost some of its influence because of its not being on board with some of the U.S. policies.

The idea is that to get our priorities straight, let’s first try to get the analysis right, and then try to be influential.

1 Thielmann served two tours at INR, leaving in September 2002 as the director of the Office of Strategic, Proliferation and Military Affairs.

2 Joseph Wilson, a retired ambassador, accused the George W. Bush administration of lying about alleged purchases of uranium by Iraq from Niger. The original public accusation was published in the New York Times as Joseph C. Wilson, IV, “Opinion: What I Didn’t Find in Africa,” The New York Times, July 6, 2003, https://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/06/opinion/what-i-didn-t-find-in-africa.html.

3 Thielmann spoke in detail on these issues at an Arms Control Association Press Briefing at the National Press Club on July 9, 2003, titled: “Iraq’s Weapons of Mass Destruction: Reassessing the Prewar Assessments.” For the transcript, see: https://www.armscontrol.org/events/2003-07/iraqs-weapons-mass-destruction-reassessing-prewar-assessments

4 “Most analysts believe that North Korea probably will test a Taepo Dong-2 this year, unless delayed for political reasons,” from National Intelligence Council, “Foreign Missile Developments and the Ballistic Missile Threat to the United States Through 2015,” September 1999, available at https://irp.fas.org/threat/missile/nie99msl.htm.

5“[Signals intelligence] information was presented in such a manner as to preclude responsible decisionmakers in the Johnson administration from having the complete and objective narrative of events of 4 August 1964. Instead, only [signals intelligence] that supported the claim that the communists had attacked the two destroyers was given to administration officials,” from Robert J. Hanyok, “Skunks, Bogies, Silent Hounds, and the Flying Fish: The Gulf of Tonkin Mystery, 2-4 August 1964,” Cryptologic Quarterly, Feb. 24, 1998, available at https://www.nsa.gov/portals/75/documents/news-features/declassified-documents/gulf-of-tonkin/articles/release-1/rel1_skunks_bogies.pdf, p. 3