"Though we have achieved progress, our work is not over. That is why I support the mission of the Arms Control Association. It is, quite simply, the most effective and important organization working in the field today."

U.S., Marshall Islands Grapple With Nuclear Legacy

November 2022

By Daryl G. Kimball and Chris Rostampour

Negotiators from the Marshall Islands are insisting that the United States address long-standing health and environmental problems created by U.S. nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific Island chain in their discussions on an agreement governing their relationship.

The agreement, known as the Compact of Free Association, defines the terms of U.S. economic assistance, allows Marshallese to live and work in the United States, and grants the United States the right to operate military facilities in the region, including Kwajalein Missile Range. It also excludes activities by the militaries of other countries without U.S. permission.

The agreement, known as the Compact of Free Association, defines the terms of U.S. economic assistance, allows Marshallese to live and work in the United States, and grants the United States the right to operate military facilities in the region, including Kwajalein Missile Range. It also excludes activities by the militaries of other countries without U.S. permission.

U.S. and Marshallese representatives began negotiations earlier this year on renewing the 20-year-old compact, which expires in October 2023. In March, U.S. President Joe Biden appointed Joseph Yun as a special presidential envoy for the negotiations.

In September, the Marshallese delegation declared a pause in the negotiations until Washington shows greater willingness to address ongoing health, environmental, and economic issues resulting from Cold War-era testing in their homeland.

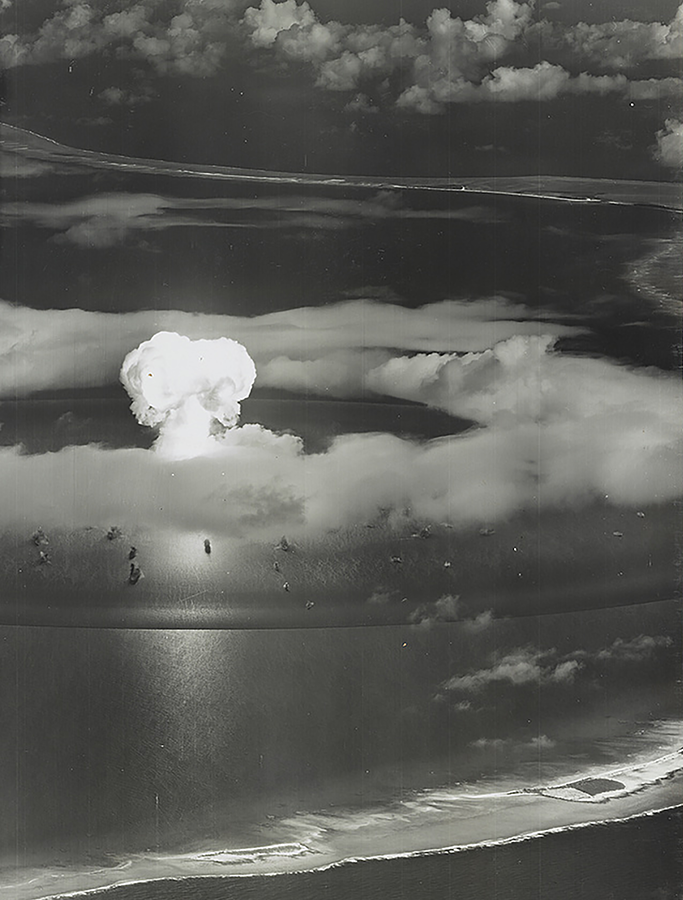

The 67 U.S. atmospheric nuclear weapons tests between 1946 and 1958—23 at Bikini Atoll and 44 at Enewetak Atoll—spewed radiation over the Marshall Islands and produced a total explosive power of 108.5 megatons (TNT equivalent). That was about 100 times the total yield of all atmospheric tests conducted at the Nevada Test Site in the United States.

As a result, islanders still suffer such health and environmental effects as elevated cancer rates and enduring displacement from contaminated areas. But to this day, the only individuals considered by the United States as exposed to radiation effects were those physically present at Rogelap, Ailinginae, or Utrok atolls at the time of the “Bravo” nuclear test on March 1, 1954.

The chair of the Marshall Island’s National Nuclear Commission, Alson Kelen, told Agence France-Presse, “We know the big picture: bombs tested, people relocated from their islands, people exposed to nuclear fallout. We can’t change that. What we can do now is work on the details for the funding needed to mitigate the problems from the nuclear legacy.”

The U.S. State Department released a statement on Sept. 23 saying that Yun is prepared “to continue to advance the discussions” with the government of the Marshall Islands.

At a two-day summit in Washington that ended Sept. 29 between the United States and representatives from 14 Pacific Island states, including the Marshall Islands, participants agreed to strengthen their partnership. Although the United States had reportedly objected to such language in the run-up to the meeting, the joint summit statement acknowledged “the nuclear legacy of the Cold War” and stated that “the United States remains committed to addressing the Republic of the Marshall Islands’ ongoing environmental, public health…, and other welfare concerns.”

Under the existing agreement, the United States is responsible for providing radiation-related health care services and continued monitoring and environmental assessments on the affected atolls. One area of particular concern is Enewetak, where less than 1 percent of the plutonium and associated transuranic radionuclides from testing activities at the atoll are contained in the Runit Dome structure, meaning that the rest of the radioactive contamination remains in the Enewetak lagoon.

In a speech at the United Nations on Sept. 21, Marshall Islands President David Kabua said his nation has a “strong partnership” with the United States but “it is vital that the legacy and contemporary challenges of nuclear testing be better addressed.” Underscoring the importance of the issue for Pacific islanders, the Marshall Islands, with the backing of Fiji, Nauru, Samoa, Vanuatu, and Australia, advanced a formal resolution at the UN Human Rights Council on Oct. 6 requesting assistance “in the field of human rights and to provide humanitarian assistance and capacity building” to the Marshall Islands’ National Nuclear Commission in advancing its national strategy for nuclear justice.

India, the United Kingdom, and the United States countered by saying the rights council was not the appropriate forum to discuss the issue. The U.S. delegate asserted that “the United States has accepted and acted on its responsibility to the people of the Republic of the Marshall Islands concerning nuclear testing” through the compact. Nevertheless, the resolution was adopted without a vote.