U.S., UK Pledge Nuclear Submarines for Australia

October 2021

By Julia Masterson

Australia could become the first non-nuclear-weapon state to field a nuclear-powered submarine as part of a new trilateral security partnership with the United States and United Kingdom known as AUKUS. The initiative was unveiled at a joint virtual press conference held Sept. 15.

All three nations emphasized that Australia will not acquire nuclear weapons and that they will uphold their commitment to global nonproliferation standards. Even so, the decision by the United States and the UK to equip Australia with nuclear submarines has heightened proliferation concerns because the U.S. and UK submarines are powered by on-board reactors fueled with highly enriched uranium (HEU).

All three nations emphasized that Australia will not acquire nuclear weapons and that they will uphold their commitment to global nonproliferation standards. Even so, the decision by the United States and the UK to equip Australia with nuclear submarines has heightened proliferation concerns because the U.S. and UK submarines are powered by on-board reactors fueled with highly enriched uranium (HEU).

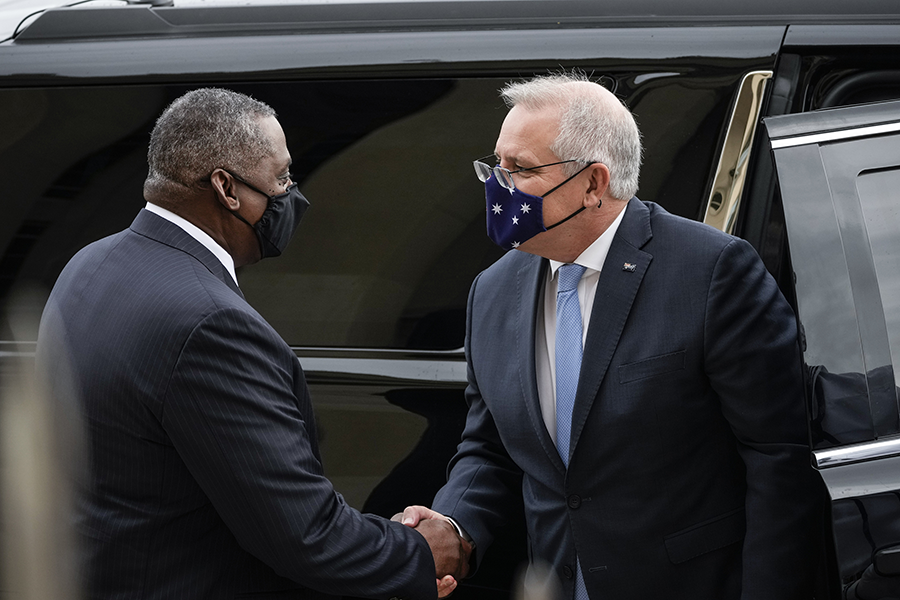

The objective of the new trilateral alliance is to ensure “peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific [region] over the long term,” U.S. President Joe Biden said during the joint appearance unveiling the initiative alongside Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson on video monitors.

“We need to be able to address both the current strategic environment in the region and how it will evolve because the future of each of our nations, and indeed the world, depends on a free and open Indo-Pacific, enduring and flourishing in the decades ahead,” Biden added.

The United States has shared nuclear submarine propulsion technology only with the UK, a product of a series of Cold War agreements aimed to counter Soviet influence in Europe.

The UK Royal Navy operates three nuclear-powered submarine systems: the Vanguard-class ballistic missile submarine and the Astute- and Trafalgar-class attack submarines. Johnson said the AUKUS partnership will provide “a new opportunity to reinforce Britain’s place at the leading edge of science and technology, strengthening our national expertise.”

Morrison said that Australia will work with Washington and London over the next 18 months “to seek to determine the best way forward to achieve” a conventionally armed nuclear-powered submarine fleet. He also said that the submarines will be constructed “in Australia in close cooperation” with the UK and the United States. The submarines will reportedly be finished in time to be fielded in the 2040s. Early reports suggest Australia may lease U.S. or UK nuclear-powered submarines in the meantime, but the details remain unclear.

At a press conference in Canberra on Sept. 16, Morrison noted that “[n]ext-generation nuclear-powered submarines will use reactors that do not need refueling during the life of the boat. A civil nuclear power capability here in Australia is not required to pursue this new capability.”

A senior Biden administration official appeared to confirm on Sept. 20 that the vessels will be powered with HEU, as UK and U.S. submarines are, when they commented on Australia’s fitness for “stewardship of the HEU.” It remains unclear who would supply Australia with the fissile material necessary to fuel the submarines or whether the nuclear-powered submarines might be provided through a leasing arrangement.

Another unknown is whether the submarine design will be based on existing U.S. or UK attack submarines or an entirely new design. One of the reasons that Australia may lease U.S. or UK vessels in the near term is to “provide opportunities for us to train our sailors, [to] provide the skills and knowledge in terms of how we operate,” Australian Defense Minister Peter Dutton told reporters Sept. 19, suggesting the new submarines may share a similar design.

The AUKUS initiative is not limited to the new submarine project. It will also facilitate the sharing of information in a number of technological areas, including artificial intelligence, underwater systems, and quantum, cyber-, and long-range strike capabilities. Morrison said Australia will also enhance its long-range strike capabilities through the purchase of Tomahawk cruise missiles and extended range Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missiles.

The three leaders were careful not to attribute the new trilateral security initiative as a response to concerns about expanding Chinese military capabilities. In February, as part of a growing U.S. emphasis on prioritizing competition with Beijing, Biden announced a new Defense Department task force charged with assessing U.S. military strategy toward China.

Nevertheless, Chinese officials were quick to condemn the AUKUS initiative. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian said on Sept. 16 that “the nuclear submarine cooperation between the U.S., UK, and Australia has seriously undermined regional peace and stability, intensified the arms race and undermined international nonproliferation efforts.”

China also expressed concerns about the proliferation risks posed by the initiative. Lijian warned that “the international community, including Australia’s neighboring countries, has full reason to question whether Australia is serious about fulfilling its nuclear nonproliferation commitments.”

Australian, UK, and U.S. officials have endeavored to assure the international community that the initiative does not pose a heightened proliferation risk. A senior Biden administration official said on Sept. 15 that “Australia, again, does not seek and will not seek nuclear weapons. This is about nuclear-powered submarines.” But they noted the novelty of the circumstance, adding, “[T]his is frankly an exception to our policy in many respects.”

Aidan Liddle, the UK ambassador to the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva, told Arms Control Today in an email Sept. 21 that “[a]ll three parties involved are absolutely committed to the [nuclear] Non-Proliferation Treaty [NPT] and have a long track record of working to uphold and strengthen the global counter-proliferation regime.”

“We have spoken to the [International Atomic Energy Agency] Director[-]General about this, and we will keep in close touch with the IAEA as we investigate the safeguards implications of the programme during the next phase of work,” said Liddle. He added, “[W]e will ensure that we are fulfilling our international obligations and giving absolute confidence that no HEU will be diverted for weapons purposes.”

Most nonproliferation experts, however, say the concern is not necessarily with Australia’s intentions but the precedent that the nuclear-powered submarine-sharing scheme would set. Although Australia’s new submarines would be conventionally armed, they clearly would be deployed for military use and will reportedly utilize HEU, which can also be used for nuclear weapons.

Washington has reached nuclear cooperation agreements for the exchange and transfer of civil nuclear material, equipment, and technology for peaceful purposes with many non-nuclear-weapon states. But military-relevant naval nuclear technology transfers are not covered under these agreements, including the U.S.-Australian agreement for nuclear cooperation that was signed in 2010.

In a Sept. 21 letter to the editor published in The New York Times, Rose Gottemoeller, former U.S. undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, criticized the proposal to share HEU-fueled submarines with Australia. The proposal, she wrote, “has blown apart 60 years of U.S. policy” designed to minimize HEU use. “Such uranium makes nuclear bombs, and we never wanted it in the hands of nonnuclear-weapon states, no matter how squeaky clean,” she said.

As recently as May 2021, the UK and United States declared that they wanted to “reinvigorate” efforts to minimize the use of HEU, according to the official statement laying out the goals for the G7 Global Partnership Against the Spread of Weapons of Mass Destruction. (See ACT, June 2021.) Reducing the production and use of HEU “enjoys broad support but requires more solid political support,” the statement said.

Senior Biden administration officials have called the decision concerning Australia “a one-off,” implying that similar arrangements would not be made with other U.S. allies.

Despite support for the new initiative among the three capitals, the AUKUS partnership risks undermining U.S. and UK relations with allies, particularly France. Australia signed on to the nuclear submarine acquisition scheme after abandoning a $66 billion deal with France for the construction of 12 conventionally powered submarines. Negotiations to establish the AUKUS initiative took place in secret for six months, and the French were not privy to those discussions.

In her Sept. 21 letter to the editor, Gottemoeller criticized the submarine deal’s lack of “strategic imagination” and noted that “what we needed was a three-cornered billiard shot—pivot to Asia, yes, but keep our European allies on board.”

“I suggest bringing the French to the table,” Gottemoeller, who was also NATO’s deputy secretary-general from 2016 until 2019, concluded. The French utilize low-enriched fuel for their naval propulsion, which, if shared with Australia, would pose a dramatically lower proliferation risk than HEU, she wrote.

Following the AUKUS announcement, Paris recalled its ambassadors from the United States and Australia. French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drain and Defense Minister Florence Parley said in a joint statement that “the American choice to exclude a European ally and partner such as France from a structuring partnership with Australia, at a time when we are facing unprecedented challenges in the Indo-Pacific region, whether in terms of our values or in terms of respect for multilateralism based on the rule of law, shows a lack of coherence that France can only note and regret.”

Paris also cancelled a French-UK defense minister’s summit scheduled for the week of Sept. 20.