“Right after I graduated, I interned with the Arms Control Association. It was terrific.”

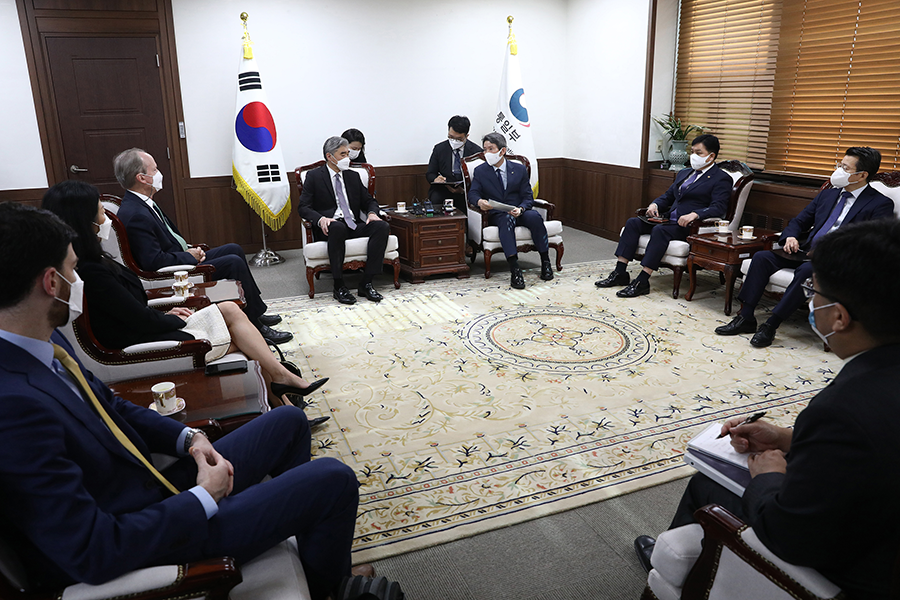

Hope and Concern in Seoul

July/August 2021

By Manseok Lee and Hyeongpil Ham

With the release of President Joe Biden’s new North Korea policy, a protracted tug of war has begun between the United States and North Korea to gain the upper hand in negotiations on the North’s nuclear weapons program. That will continue until Pyongyang decides it can no longer withstand international sanctions or Washington decides that the sanctions are no longer effective given the North’s rapidly growing nuclear capabilities. The former case would be an auspicious start for a successful denuclearization process, but the latter could result in North Korea being accepted as a nuclear-armed state.

Although national security experts in South Korea have welcomed the new U.S. policy overall, concerns remain that Biden’s approach will pave the way for North Korea’s nuclear status to become a fait accompli. That would be unacceptable to Seoul, with dire consequences for the security of South Korea and the region. Therefore, the United States should carefully navigate the pitfalls that could result in a negotiated outcome beneficial to Pyongyang but detrimental to the interests of Washington and its regional allies.

Although national security experts in South Korea have welcomed the new U.S. policy overall, concerns remain that Biden’s approach will pave the way for North Korea’s nuclear status to become a fait accompli. That would be unacceptable to Seoul, with dire consequences for the security of South Korea and the region. Therefore, the United States should carefully navigate the pitfalls that could result in a negotiated outcome beneficial to Pyongyang but detrimental to the interests of Washington and its regional allies.

The South Korean View

Shortly after Biden took office, South Korean strategists worried that his administration would be unable to make North Korea a priority due to pressing domestic issues and other international concerns such as Taiwan, the South and East China seas, and the human rights crisis in Xinjiang. The strategists were also concerned that the dialogue between the United States and North Korea would be suspended because, during the final presidential debate, Biden accused President Donald Trump of “legitimatizing North Korea,” saying he would meet with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un only if Pyongyang agreed to “draw down [its] nuclear capacity.”1 These concerns seem to have been mitigated during the following months as Seoul and Washington held a series of discussions about the emerging U.S. approach toward North Korea and prepared for the South Korean-U.S. summit in Washington on May 21.

Above all, these consultations convinced the Biden administration to formalize the common goal of denuclearizing the Korean peninsula, not just North Korea, thus reaffirming the goals articulated by Trump and Kim after their 2018 Singapore summit and in the Panmunjon Declaration issued by Kim and South Korean President Moon Jae-in that same year. These measures could lay the groundwork for bringing North Korea back to the negotiating table by avoiding the language Pyongyang has opposed. Furthermore, respecting these previously agreed official statements is crucial to maintaining the continuity of negotiations.

Biden has also dispelled South Korea’s concern that the nuclear issue could be pushed off of Washington’s agenda by underscoring his intention to engage North Korea through the appointment of veteran diplomat Sung Kim as special representative for North Korea policy. This marked a dramatic change of position because the administration had originally intended to keep the position vacant for a time.2

Nevertheless, there is a lingering worry that if Pyongyang exploits the complexity and uncertainty of the denuclearization process to corner Washington, the administration’s phased approach could have the undesired consequence of ensuring that North Korea’s possession of nuclear weapons becomes a foregone conclusion.3

Pyongyang has long sought to make Washington and Seoul anxious by creating an impression that North Korea is successfully enduring sanctions through ideological fortitude and cooperation with China and that its nuclear programs are proceeding smoothly. If Washington were to determine that international sanctions against the Kim regime have become ineffective and that North Korea’s nuclear capabilities were developing rapidly and without impediment, the administration could feel pressured to wrap up any negotiations in a hurry.

Against this backdrop, it is understandable that some South Korean experts are gravely concerned that Washington would choose to reach an interim agreement with Pyongyang for the sake of more limited gains, such as capping North Korea’s intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) program—the element of its weapons program that most threatens U.S. national security—in exchange for the partial or complete lifting of U.S. sanctions.4 In that case, incomplete denuclearization would become a lasting condition, and U.S. allies in the region would be left permanently exposed to the dangers of North Korea’s intermediate- and short-range nuclear missiles.

Failing to completely denuclearize North Korea would have significant consequences for East Asian security. For one, it would cause U.S. allies, such as South Korea and Japan, to question whether the United States really takes their security seriously. The United States would then find it more difficult to assure them of the reliability of its extended deterrence. Then, some analysts fear, these allies could seek to acquire nuclear weapons as a self-help measure by calling on the United States to station nuclear weapons in the region or developing their own.5

Furthermore, if North Korea were to be recognized as a nuclear-armed state and international sanctions were reduced or lifted, that would shake the foundations of the global nuclear nonproliferation regime. In particular, it would encourage other potential proliferators to believe that even after undermining international norms, they will eventually get to keep their nuclear weapons if they can withstand sanctions for some period of time.

Kim’s Playbook

For the United States, the path to North Korean denuclearization is riddled with the pitfalls that Pyongyang is certain to create. To avoid the unwanted outcome of incomplete denuclearization, Biden should be careful not to fall into these traps. His ability to navigate these negotiations successfully will determine whether he can mitigate allied concerns and ultimately persuade Pyongyang to dismantle its nuclear program for good.

Washington should be wary of underestimating or overestimating North Korea’s nuclear program. Pyongyang has long sought to conceal and downplay its nuclear capabilities. Thus, it is always critical to identify the hidden nuclear facilities and weapons stockpiles.6 Pyongyang also has an incentive to exaggerate its capabilities because the operational nuclear weapons that it claims to already possess represent bargaining chips that can be traded away in exchange for the lifting of sanctions and the provision of economic aid.

North Korea will present its nuclear capabilities as greater than they really are through demonstrations at military parades and weapons tests and will claim that its nuclear deterrent is continuously growing. If Washington overestimates the North’s capabilities and offers excessive incentives, it could lose bargaining power early and undermine its ability to persuade Pyongyang to genuinely engage in negotiations until it achieves complete denuclearization.

North Korea will present its nuclear capabilities as greater than they really are through demonstrations at military parades and weapons tests and will claim that its nuclear deterrent is continuously growing. If Washington overestimates the North’s capabilities and offers excessive incentives, it could lose bargaining power early and undermine its ability to persuade Pyongyang to genuinely engage in negotiations until it achieves complete denuclearization.

Washington should be aware that Pyongyang will exploit the extremely complex nature of the denuclearization process to ensure its possession of nuclear weapons becomes a fait accompli.7 Nuclear programs comprise diverse parts, such as fissile material, reactors, assembly and storage facilities, nuclear warheads, delivery vehicles, and personnel. Denuclearization involves time-consuming procedures such as the declaration of inventories, inspection of facilities, dismantlement, and monitoring. The highly technical nature of the denuclearization process offers North Korea many opportunities to renege on its commitments at some point in the future.8

If Pyongyang fails to deliver on its promises to dismantle part of its nuclear program or violates obligations as it did during the six-party talks that took place between 2003 and 2009, the negotiations would have to start over. If North Korea’s nuclear capability continued to grow in the meantime, Washington could face strong domestic pressure to wrap up the negotiations quickly, even if it means incomplete denuclearization.

North Korea may try to strike a deal on issues related to the security of U.S. allies in the region, such as permanently halting the U.S.-South Korean joint military exercises or facilitating a partial withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Korea. It is understandable that issues concerning the security of U.S. allies be treated as bargaining chips toward the ultimate goal of complete denuclearization.

Yet, the allies should be consulted before these issues are placed on the negotiating table. Otherwise, proposals intended to encourage North Korea to enter into dialogue could undermine the security of key allies, damage their relationships with the United States,9 and sour unified efforts to advance denuclearization. Such disharmony between allies would only benefit North Korea.

Washington should be prepared for a scenario in which Pyongyang leverages its relationship with Beijing to improve its bargaining position. China’s ties with North Korea are complex. Although Pyongyang’s decision to engage in nuclear proliferation and risky provocations implies that it has chosen to willfully ignore Beijing’s security interests, North Korea remains a strategically important neighbor for China.10

For this geostrategic reason, Beijing prefers the status quo and will adamantly oppose North Korea becoming a neutral or pro-U.S. country.11 For example, when the United States appeared to be pushing North Korea to the brink of war in 2017, China responded by issuing stark warnings and participating in UN sanctions in an effort to pressure Pyongyang to stand down. Yet, when diplomatic efforts between Washington and Pyongyang accelerated in 2018, Beijing betrayed its concern about North Korea drifting out of its orbit by moving decisively to reassert itself through an unprecedented series of summits between Xi Jinping and Kim, who met five times between 2018 and 2019, including the first visit by a Chinese leader to Pyongyang in 14 years.12

North Korea is well aware of the strategic value it holds for China and of the priority that Beijing assigns to maintaining the status quo on the Korean peninsula over denuclearization. Therefore, Pyongyang will try to reduce the effectiveness of international sanctions through cooperation with Beijing, and it may escalate the crisis in order to draw China’s support when the situation is unfavorable. Consequently, a strengthened Sino-North Korean coalition would weaken Washington’s bargaining position and pressure it to offer concessions first.

The ultimate success of the denuclearization process rests on whether North Korea can be made to feel that it can no longer withstand sanctions, continue its nuclear development, or hide its nuclear capabilities and that its existing nuclear weapons have low strategic utility. Only then will Pyongyang stop dragging its feet and engage seriously in negotiations. To this end, Washington should keep the following recommendations in mind.

The United States and its allies in the region should preserve a credible deterrence posture against North Korea. The United States’ extended nuclear deterrence and its allies’ advanced conventional deterrence are key capabilities in reducing the strategic utility of North Korea’s nuclear weapons. Until fully denuclearized, North Korea will continue to have nuclear warheads and the missiles to deliver them and could be tempted to play these cards whenever the situation becomes unfavorable. Diplomatic engagement by Washington and its allies with Pyongyang based on a robust deterrent will discourage North Korea’s miscalculation with regard to the usefulness of its nuclear weapons.

International sanctions must be sustained and implemented thoroughly until full-fledged negotiations between Washington and Pyongyang begin. Even if negotiations begin and Washington agrees to partially lift sanctions in exchange for North Korea’s partial reduction of its nuclear capabilities, doing so should not be allowed to weaken the remaining sanctions regime. If sanctions are lifted too early and North Korea is allowed to revive its economy, it would no longer have an incentive to abide by the terms of a protracted denuclearization process and would instead gain incentives to further advance its nuclear capabilities. Furthermore, once the sanctions have been reduced, it may be difficult to ratchet them up again.

The United States and its regional allies, such as South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and Australia, should increase their cooperation toward the goal of complete denuclearization by presenting a unified, organized front against Pyongyang. They are key to maintaining a robust sanctions regime and to preventing North Korea from trading nuclear-related materials. Their integrated intelligence activities will help identify when North Korea is concealing or exaggerating its nuclear capabilities. Finally, U.S. allies are major stakeholders in the North Korean nuclear issue and will share the burden of whatever outcome these negotiations yield. The United States should act as the fulcrum around which these countries can unite and work together.

At some point, the denuclearization negotiations should be expanded into multilateral negotiations including China. Beijing is unlikely to welcome or accept any outcome reached by Washington and Pyongyang bilaterally, and Chinese officials and scholars have expressed the view that China may agree to participate in multilateral denuclearization talks.13 Thus, Washington should consult with Beijing regarding the timing of a transition to multilateral negotiations to dissuade China from offering competing incentives to North Korea that could strengthen Pyongyang’s endurance against international sanctions.

Biden’s emphasis on the importance of enhancing allied security and strengthening cooperation among countries with shared values has bolstered the allies’ confidence in his approach. Nevertheless, the stability of the Korean peninsula would rapidly deteriorate if the United States were to act rashly with regard to the North Korean nuclear issue. The administration, together with its regional allies and partners, needs to tackle the 30-year challenge that is the North Korean nuclear problem in a flexible but cautious manner.

ENDNOTES

1. Kim Gamel, "Biden Calls North Korean Leader a ‘Thug’ but Says He’d Meet Kim If Denuclearization Is Agreed," Stars and Stripes, October 23, 2020.

2. Josh Rogin, "Biden’s North Korea Strategy: Hurry Up and Wait," The Washington Post, May 5, 2021.

3. Duhyun Cha, “Prospect of Biden’s North Korea Policy, [차두현, 바이든 행정부의 대북정책 전망: 쟁점, 북한의 대응, 그리고 한국의 과제]", Issue Brief, Asan Institute for Policy Studies, May 18, 2021, https://www.asaninst.org/contents/%EB%B0%94%EC%9D%B4%EB%93%A0%ED%96%89%EC%A0%95%EB%B6%80%EC%9D%98%EB%8C%80%EB%B6%81%EC%A0%95%EC%B1%85-%EC%A0%84%EB%A7%9D-%EC%9F%81%EC%A0%90-%EB%B6%81%ED%95%9C%EC%9D%98-%EB%8C%80%EC%9D%91%EA%B7%B8/. (In Korean)

5. For example, Toby Dalton and Ain Han, "Elections, Nukes, and the Future of the South Korea-U.S. Alliance," Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 26, 2020, https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/10/26/elections-nukes-and-future-of-south-korea-u.s.-alliance-pub-83044.

6. For example, during the 2019 Hanoi summit, Pyongyang’s representatives spoke as if there were no nuclear facilities in North Korea other than Yongbyon. See Edward Wong, “Trump’s Talks With Kim Jong-un Collapse, and Both Sides Point Fingers,” The New York Times, February 28, 2019.

7. William J. Broad and David E. Sanger, “North Korea Nuclear Disarmament Could Take 15 Years, Expert Warns,” The New York Times, May 28, 2018.

8. Cui Lei, “Why It’s Nearly Impossible to Denuclearize North Korea,” The Diplomat, June 22, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/06/why-its-nearly-impossible-to-denuclearize-north-korea/.

9. For example, immediately following the Singapore summit in 2018, Washington unilaterally announced the suspension of South Korean-U.S. joint exercises without first securing an explicit concession from North Korea on reducing its nuclear threats. This led to security concerns for South Korean strategists. See Josh Smith and Phil Stewart, “Trump Surprises With Pledge to End Military Exercises in South Korea,” Reuters, June 12, 2018; Kim Gwi-geun, “Trump’s Remarks About ‘Suspending Joint Exercises’…Ministry of Defense ‘Embarrassed,’” Yonhap News, June 12, 2018, https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20180612162400014 (in Korean).

10. Evans J.R. Revere, “Lips and Teeth: Repairing China-North Korea Relations,” Brookings Institution, November 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/FP_20191118_china_nk_revere.pdf.

11. Yun Sun, Statements During the 38 North Webinar “Biden’s North Korea Policy Review: Perspectives From the Region,” April 19, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=prC9a9m3NDk.

13. Jeong Seong-jang, “Biden Administration’s North Korea Policy Review and Strategic Cooperation Direction Between Korea and the U.S.,” Sejong Policy Brief, No. 2021-8 (April 29, 2021), pp. 14–18, https://www.sejong.org/boad/1/egofiledn.php?conf_seq=3&bd_seq=5945&file_seq=16429 (in Korean).

Manseok Lee is a U.S.-Asia Grand Strategy predoctoral fellow at the University of Southern California and a Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Berkeley. Hyeongpil Ham received his Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He has worked for more than 30 years at South Korea’s Ministry of National Defense, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Korea Institute for Defense Analyses. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official positions of the South Korean government.