"Though we have achieved progress, our work is not over. That is why I support the mission of the Arms Control Association. It is, quite simply, the most effective and important organization working in the field today."

Enhancing Space Security: Time for Legally Binding Measures

December 2020

By Victoria Samson and Brian Weeden

A growing chorus of top U.S. military chiefs and bipartisan political leaders has voiced alarms on the proliferation of space threats. Yet, those same voices have been much quieter on the potential solutions, aside from calls for the United States to grow even stronger. It is time for the United States to return to its historical role and propose additional legally binding measures to enhance the security and stability of space, including space arms control, as part of a more holistic approach that includes voluntary measures as well.

Doing so will not be easy. Space is a unique domain, with its own physical, legal, and political dynamics. Hardly any of the work necessary to develop the conceptual foundations for space arms control has been done, let alone to define how to meet the conditions for measures that are equitable and verifiable and enhance U.S. national security as laid out in current U.S. policy. All of these, however, are challenges that should be overcome, not insurmountable obstacles, because ensuring the long-term sustainability and security of space for the benefit of all is an end result too important to ignore.

Doing so will not be easy. Space is a unique domain, with its own physical, legal, and political dynamics. Hardly any of the work necessary to develop the conceptual foundations for space arms control has been done, let alone to define how to meet the conditions for measures that are equitable and verifiable and enhance U.S. national security as laid out in current U.S. policy. All of these, however, are challenges that should be overcome, not insurmountable obstacles, because ensuring the long-term sustainability and security of space for the benefit of all is an end result too important to ignore.

Emerging Threats to Space Security and Stability

Space capabilities are a crucial part of U.S. national security. It is difficult to find a current U.S. military operation anywhere in the world that does not rely on space data or services in some way. Satellites also provide critical intelligence data on potential future threats, as well as warning of imminent attacks on the United States and its allies. In addition to these core military and intelligence applications, space capabilities underpin the ability to predict and warn the American public about severe weather and natural disasters and monitor the changing climate. Space capabilities also are integrated into national and global transportation, financial, and communications systems.

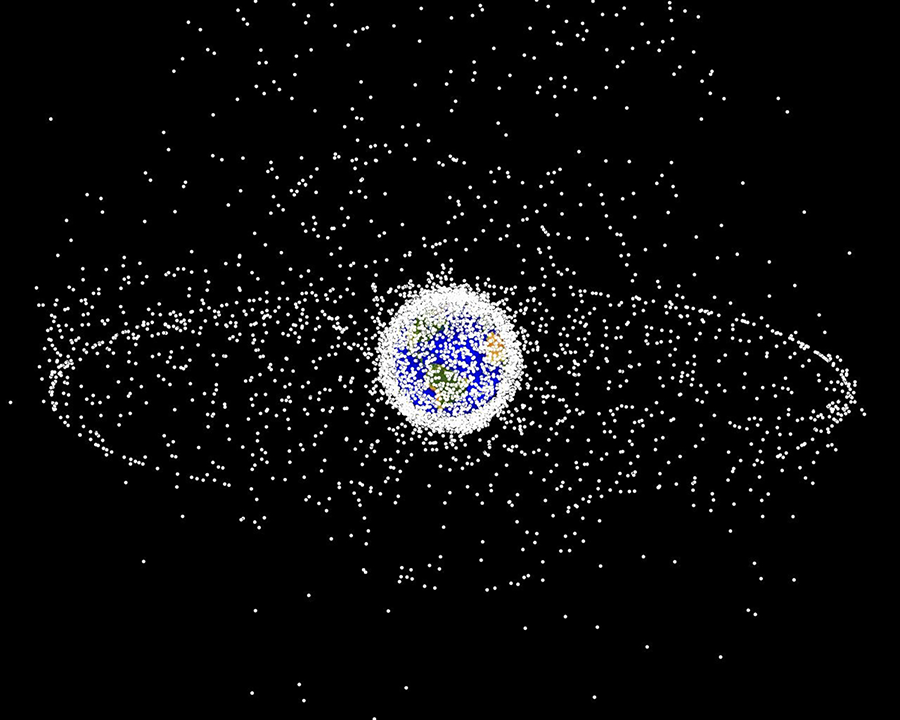

The reliance on and importance of space capabilities for national security has sparked investment in the development of offensive counterspace capabilities to deceive, disrupt, deny, degrade, or destroy space systems during times of heightened tensions and armed conflict. These capabilities include nondestructive jamming and interference with satellite signals and functions, cyberattacks, and even outright destruction. Primarily, Russia and China are investing in these capabilities; but France, India, Iran, Japan, North Korea, and the United States are also active.1 As counterspace technologies mature, they will likely further proliferate to other countries and potentially to nonstate actors. Since 2005, there have been 20 anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons tests in space or against satellites by four different countries, a rate of testing that has not happened since the 1960s.2

In addition to outright weapons testing, there have been a growing number of concerning activities in space. Many of these involve rendezvous and proximity operations (RPOs), or deliberately close approaches of other space objects by satellites. Although RPOs have been conducted since the 1960s as part of human spaceflight operations, robotic RPO capabilities over the last two decades have been more widely developed for a range of commercial, civil, and national security applications. There is growing concern that such activities might increase tensions between countries or could be misinterpreted as a hostile action that precipitates an armed attack.

The current international legal framework is largely permissive, at least implicitly, toward the development, testing, and deployment of counterspace capabilities and conducting RPOs. While the 1967 Outer Space Treaty bans the placement of nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction in outer space, there are generally no specific restrictions on testing or deployment of non-nuclear weapons in space. And while the Charter of the United Nations prohibits aggression in space just as it does terrestrially, there is no consensus on what constitutes a use of force or armed attack against space capabilities or how international humanitarian law applies to an armed conflict that extends into space. There is also a lack of consensus on norms of behavior for conducting military activities in space during peacetime, including close approaches of other satellites.

Top U.S. military and political leaders have voiced alarm over the proliferation of space threats, but so far, there has been little willingness to discuss legally binding measures to restrict or halt them. The main strategy of the United States has been to increase the resilience of its own space systems and develop its own offensive counterspace capabilities with the goal of deterring attacks and winning a war should deterrence fail.3 The United States has also voiced support for voluntary measures on some categories of space activities, such as mitigating the creation of orbital debris and sharing space situational awareness (SSA) data, but has not put forward specific proposals related to military or national security activities in space.

It is time for the United States to return to its historical role and propose additional legally binding measures to enhance the security and stability of space, including space arms control. The United States has played a key role in developing and enforcing legally binding security mechanisms in nearly every other domain of military activity and has long recognized the value these mechanisms can play in enhancing U.S. national security and international stability. As the space power of potential U.S. adversaries grows, so too do the negative implications of that space power for U.S. interests. The United States needs to decide what types of space capabilities and power relationships present a threat to U.S. national security and the best way to mitigate or remove that threat.

Yet, it is not a matter of simply replicating for space the legal mechanisms and controls that have proven successful in other domains. Space is a unique arena, with its own physical, legal, and political dynamics. Other domains can provide useful context and examples, but cannot be applied wholesale. Additionally, a considerable amount of work is needed to develop the strong conceptual foundations for space arms control, similar to what was done for nuclear arms control.

Multilateral Forums

Various multilateral forums have discussed current space security challenges, but these discussions have yielded very limited progress. Most of the proposals for legally binding agreements on space security issues have gone nowhere largely because their proponents and opponents were not acting in good faith. There has been some success with non-legally binding agreements, but few of them address security issues.

The vast majority of legally binding proposals on space security have emerged within the Conference on Disarmament (CD), which has had an agenda item on the prevention of an arms race in outer space since the 1980s.4 These efforts have never taken root, in part due to the inability of the CD to agree on a work plan.5 In addition to this agenda item, the CD deals with a wide range of contentious security issues, including nuclear disarmament, a fissile material cutoff treaty, and negative security assurances, and various states have sought to block progress on some or all of these issues by tying them together.

The vast majority of legally binding proposals on space security have emerged within the Conference on Disarmament (CD), which has had an agenda item on the prevention of an arms race in outer space since the 1980s.4 These efforts have never taken root, in part due to the inability of the CD to agree on a work plan.5 In addition to this agenda item, the CD deals with a wide range of contentious security issues, including nuclear disarmament, a fissile material cutoff treaty, and negative security assurances, and various states have sought to block progress on some or all of these issues by tying them together.

Specific to space security, Russia and China have been the most active in the CD by repeatedly proposing initiatives to ban placement of weapons in outer space, but these measures have never gained widespread international acceptance. They proposed an agreement titled the Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space, the Threat or Use of Force Against Outer Space Objects (PPWT) in 2008, which was modified somewhat in 2014 in an effort to meet concerns about its lack of verification, but has not seen much progress toward adoption since that time.6 More recent proposals for no first placement of weapons in space have not had much traction either, although a UN General Assembly resolution of support was passed in November 2019.7

Between 2017 and 2019, three different UN bodies tried and failed to make any significant progress on space security issues in a multilateral setting. In February 2018, the CD agreed to form four subsidiary bodies to deal with individual agenda items in the absence of an overall work plan. Subsidiary body three was tasked with looking at the prevention of an arms race in outer space.8 Through 2018, it met six times and was able to agree on a consensus report, which was forwarded to the CD plenary. Yet, the CD was not able to adopt a final report to send to the UN General Assembly due to political difficulties with the presidency of one member state. Instead, its final product was just a procedural report.

There are several key issues behind the current deadlock and failure of the CD. It has become a forum where states take ideological positions or air larger geopolitical grievances. On space security, this manifests in Russia and China using the proposed PPWT as a diplomatic cudgel to publicly demonize the United States on space weaponization while developing their own ground-based space weapons that would not fall under the restrictions established by the PPWT. The United States for its part has rejected any legally binding proposals on space security, instead wanting the flexibility to develop future weapons capabilities, including space-based missile defenses, while accusing Russia and China of weaponizing space.9 Thus, the United States mobilized its allies to object to the PPWT and no-first-placement proposals while never offering alternatives of its own.

As a result of the CD deadlock, there have been several attempts to discuss space security issues through other means. One of these was the 2008 proposal by the European Union for a draft code of conduct for space. The draft code was mostly a conglomeration of fairly benign, uncontroversial best practices that EU members felt would be helpful for the security and stability of space. It fell apart, however, once international negotiations began because of a lack of broader diplomatic support and disagreement over how the document should view self-defense in space. By the time the UN had a meeting on it in July 2015, its momentum had expired. Although the EU has not officially shelved the draft code, it has not had any more formal discussions on the document either.10

A more successful attempt at coming to agreement on space security principles was made by a UN group of governmental experts that met in 2012 and 2013. This space experts group had a diverse geographic representation and reached consensus on recommendations for transparency and confidence-building measures in outer space activities.11 Some of the measures included recommendations for information sharing on national policies and activities in outer space, notifications of risk reduction efforts, and voluntary visits to launch sites. Yet, implementation of these recommendations has been minimal and thus has had limited impact on space security and stability.

The UN Disarmament Commission, which is part of the General Assembly, established a working group to find ways in which the recommendations of the 2013 experts group on space transparency and confidence-building measures could be implemented.12 The working group was not able to convene in the spring of 2019 because Russian delegates had visa issues preventing them from getting to the UN meeting in New York.

In December 2017, the General Assembly asked the UN secretary-general to form an experts group on further practical measures on preventing an arms race in outer space.13 The delegates met in the summer of 2018 and spring of 2019. Part of their mandate was to look at elements of a legally binding treaty, using the proposed PPWT as a basis for discussions, and other elements that might be introduced to make an agreement on preventing an arms race in outer space work. At some points during the negotiations, it seemed that a consensus document might emerge from this experts group, but none ultimately was achieved.14

Over this same time period from 2010 to 2018, the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space concluded a very successful eight-year effort to develop voluntary guidelines for the long-term sustainability of space.15 This effort was unique in that it brought more than 90 member states together to reach consensus on issues ranging from mitigating orbital debris to sharing SSA data and space weather information and developing national policy and regulatory frameworks. Several countries, led by the United States, strongly opposed including any security issues in the sustainability discussions, arguing that they were outside the mandate of the UN committee, and opposed making the guidelines legally binding. The sustainability discussions also survived constant opposition from Russia through much of the process that arose from geopolitical tensions between the United States and Russia over the conflict in Ukraine and annexation of Crimea.

In the most recent effort, the United Kingdom proposed a General Assembly resolution in August 2020 to try and take a different tack on space security.16 The UK proposal tries to shift the space security discussion from banning or controlling specific technologies to looking at actions and behaviors in space and developing a more unified perspective on threats to space security. As a starting point, it calls for UN member states to report to the secretary-general what they believe responsible and threatening behavior in space looks like. The UK proposal survived opposition from Russia and several other countries and was adopted by the UN General Assembly First Committee in early November 2020.17

Some of these non-CD efforts have been at least partially successful, but even those achievements highlight the challenges of making progress on space security issues. All of the successful efforts have been voluntary in nature, which the United States favors but many other countries oppose. All of them have avoided tough security issues, but still had to spend years developing common understandings of terminology, convincing developed and developing states of the importance of the issue, expanding national capacity and processes to develop individual state positions, and finally navigating geopolitical storms. Most importantly, none of the successful initiatives have addressed any of the core underlying issues behind the pressing security challenges facing the space domain.

The Need for Space Arms Control

With these failures and shortcomings, the need remains for diplomatic and legal agreements to address the proliferation of counterspace capabilities and the growing instability in space. First and foremost, there must be a recognition that there is no silver bullet for solving the core space security challenges. Like many “wicked” problems,18 they are complex and will require multiple approaches that combine voluntary and legally binding efforts working together as part of a comprehensive whole. A number of concepts and ideas can serve as a starting point for further discussion on developing a substantive framework to enhance space security and stability.

Second, although many countries will need to play a role in resolving these challenges, the United States must take a leadership role. The United States is still the most powerful country in space and has the most to lose, should space devolve into an arena of unrestrained weaponization and potential armed conflict. Preventing this exact outcome was part of the impetus that drove the United States to play a major role in creating the current international legal regime in space, such as the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, that has served the United States and the world so well.

Second, although many countries will need to play a role in resolving these challenges, the United States must take a leadership role. The United States is still the most powerful country in space and has the most to lose, should space devolve into an arena of unrestrained weaponization and potential armed conflict. Preventing this exact outcome was part of the impetus that drove the United States to play a major role in creating the current international legal regime in space, such as the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, that has served the United States and the world so well.

Third, the consideration of legally binding measures in space is consistent with historical U.S. policy. Nearly every U.S. national space policy since the Eisenhower administration has endorsed pursuing space arms control and other legally binding agreements.19 The current policy, issued in June 2010 by the Obama administration, states, “The United States will pursue bilateral and multilateral transparency and confidence-building measures to encourage responsible actions in, and the peaceful use of, space. The United States will consider proposals and concepts for arms control measures if they are equitable, [are] effectively verifiable, and enhance the national security of the United States and its allies.”20 Thus, the starting point should be what those three conditions—equitable, verifiable, and U.S. national security-enhancing—might mean.

Measures That Enhance U.S. National Security

Beginning with the third of the conditions, determining how best to enhance the national security of the United States and its allies should be the starting point of any arms control discussion. Indeed, it was the realization that nuclear arms control restrictions on the Soviets could improve U.S. national security that led to some of the initial political support for nuclear arms control. Since the 1980s, however, U.S. leaders have concluded that space arms control would hinder the United States more than its potential adversaries. This emphasis on “freedom of action” stemmed from the thinking that the United States should leave its options open to be able to develop whatever space capabilities and weapons that could provide benefits in the future.

Yet, that situation is changing. Other countries, particularly China and Russia, have developed their own counterspace capabilities, and many of the underlying technologies are rapidly coming down in cost and complexity. Capabilities that were once only within the reach of the United States and perhaps the Soviet Union are now potentially available to many other countries, even nonstate and commercial actors. This commoditization and proliferation is a trend happening across the space sector and will continue to accelerate. Hence, there should be a renewed debate as to what space capabilities truly benefit U.S. national security and which ones present a threat to U.S. national security.

Most discussions of what capabilities might threaten U.S. national security more than benefit it zero in on destructive testing of ASAT weapons. Destructive ASAT weapons tests have created nearly 5,000 pieces of orbital debris since the 1960s, more than 3,000 of which still pose navigation hazards to satellites.21 Long-lived orbital debris poses a threat to critical U.S. national security assets, human spaceflight operations, and the future commercial development of space, all of which are priorities for the United States and its allies. A legally binding agreement that prevents destructive testing of ASAT weapons or at least that which generates long-lived orbital debris should be at the top of the list for consideration.

Thinking further into the future, the United States needs to consider that potential future space weapons not currently deployed today might pose more of a threat to U.S. security than benefits. A recent paper suggested that space-to-earth weapons might fall into this category because they would periodically overfly the United States and its allies and could pose an untenable threat for U.S. political leaders.22 Placing such weapons into orbit is not explicitly illegal under the existing space law regime although it does explicitly allow their unrestricted overflight of every country. Changing either of those aspects of current law might be something the United States could consider.

Verifiability

Verification is defined as any process designed to demonstrate a party’s compliance or noncompliance with an agreement or treaty. In traditional nuclear arms control, a large part of verification involves using satellites that are usually referenced by the euphemism “national technical means” to observe and measure objects and activities on earth. For example, electro-optical imagery satellites can count the number of missile silos and measure the length and diameter of ballistic missiles to determine their performance. Radio-frequency signal intercept satellites can detect and capture radar emissions and telemetry, tracking, and command signals.

Countries and special interest groups hostile to the concept of space arms control often assert that it is impossible to verify space weapons and therefore space arms control is not feasible. That is true to a point: it is extremely difficult to determine whether a satellite is a weapon, in large part because there are many ways that a satellite can be used for weapons effects. This assertion, however, hides two things. It is possible to verify many types of actions in space, such as a close approach of another object or a collision that generates large amounts of orbital debris. Also, it is more difficult to use a satellite to harm another satellite than often postulated, and militaries are much more likely to choose custom-designed weapons to achieve desired effects than try to modify a commercial or civil satellite.

Countries and special interest groups hostile to the concept of space arms control often assert that it is impossible to verify space weapons and therefore space arms control is not feasible. That is true to a point: it is extremely difficult to determine whether a satellite is a weapon, in large part because there are many ways that a satellite can be used for weapons effects. This assertion, however, hides two things. It is possible to verify many types of actions in space, such as a close approach of another object or a collision that generates large amounts of orbital debris. Also, it is more difficult to use a satellite to harm another satellite than often postulated, and militaries are much more likely to choose custom-designed weapons to achieve desired effects than try to modify a commercial or civil satellite.

From a technical perspective, the United States is already laying the foundations of space verification. SSA has been a top priority for the United States and many other countries for more than a decade now and includes monitoring and characterizing activities in space. It is precisely these capabilities that allowed the United States to publicly assert that Russia tested a space weapon in July 2020.23 This suggests that the United States already has some of the capabilities necessary to verify the testing or deployment of ASAT weapons in space. The key issue is matching existing capabilities with the legal stipulations of a future agreement and ensuring the other parties in the treaty can also feel confident in their own verification abilities. For example, only the United States currently has the ability to verify the launch of a direct-ascent ASAT weapon from earth, but several countries and commercial companies could verify that it collided with a satellite and created large amounts of orbital debris.

Equitability

The third requirement outlined in existing U.S. policy, that measures be equitable, is currently the most vague and potentially challenging to define. There is no common definition among arms control negotiators of “equitable.” At best, you could probably get practitioners to agree that it means all parties are affected by the agreement and benefit from it, but not necessarily in exactly equal ways. For example, the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty caps the number of various types of warheads and deployed ballistic missiles that the United States and Russia are allowed to have, with the cap being the same on each side. Yet, each side has flexibility on the number and types of platforms it can develop and deploy within those caps. The benefit to both countries is a limit on unrestricted arms racing and avoiding global nuclear war.

Finding agreement elsewhere has proven more difficult. The issue of equitability has stymied progress on the proposed PPWT, and the two sides of the debate on preventing an arms race in outer space do not agree on the threat that needs to be addressed, while also having different capabilities for and interests in space. The United States has integrated space enhancement capabilities into its national security infrastructure to a much higher degree than Russia and China. Russia has focused more effort on integrating counterspace capabilities, particularly electronic warfare. China is developing integrated counterspace and integrated space enhancement capabilities, although it still lags the United States in results for the latter.

Thus, restricting the development of ground-based ASAT weapons would affect Russia and China more than the United States,24 unless those restrictions also include limits on the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system capabilities the United States currently has deployed. That, however, may be politically untenable for U.S. policymakers, who have made these missile defenses the main response to nuclear threats from Iran and North Korea.

Limits or bans on deployment or testing of space-based weapons may be more equitable, but present their own political challenges, again related to nuclear weapons. Despite the massive, inherent economic and technical challenges, a vocal minority in the United States still argue strongly for a “space-based missile shield” that can theoretically protect the United States from nuclear attack. Such a capability would undermine Russian and Chinese nuclear deterrents, which is why preventing the deployment of space-based interceptors is the focal point of the PPWT. In an effort to counter U.S. satellite capabilities, Russia and China are also experimenting with co-orbital ASAT weapons of their own, which the United States considers to be a major threat. Thus, there may be a way to create a limit or ban on space-based weapons that restricts and benefits all the major parties, although not necessarily in exactly the same ways.

Although all legitimate challenges, they are not insurmountable, should the United States make an effort to meet them. During the Cold War, the United State poured considerable resources and political will into creating the intellectual foundations for nuclear arms control, establishing verification capabilities, and crafting negotiating positions that linked everything together. No such effort has been done for space in the last 20 years and would likely be necessary for any legally binding agreements on space security to be taken seriously.

Baby Steps

The prospects of legally binding agreements on space security remain distant, but the United States can take concrete actions to improve space security and stability. As a starting point, the United States, Russia, and China should discuss definitions of agreed behavior for military activities in space, in particular the interactions between their military satellites in space, akin to the discussions that led to the Incidents at Sea Agreement during the Cold War.25 As in the case of maritime operations, clarifying norms of behavior for noncooperative rendezvous and proximity operations and, where possible, providing notifications of upcoming activities can help reduce the chances of misperceptions that could increase tensions or spark conflict. As part of these discussions, the main space powers need to share their perspectives on how the existing laws of armed conflict apply to military space activities.

The United States can also lay the foundation for a ban on debris-creating ASAT weapons tests. This includes developing a whole-of-government understanding of the value of such a limitation and the required verification capabilities. Encouraging voluntary moratoriums on such testing could send a powerful political signal and counter their current international acceptance, but only as a basis for moving to a legally binding agreement, as was the case with nuclear testing. The main difference is that space agreements are likely to start at least as trilateral (the United States, Russia, and China) and later expand to include other space powers, such as some European nations, Japan, and India. Immediately pushing for a broad multilateral agreement within the UN on preventing an arms race in outer space or other space security topics would be ineffective. In this domain, the UN is more effective for normalizing ideas and agreements generated elsewhere than creating them.

Finally, throughout these discussions, the United States should recognize that space is a cross-cutting issue and likely cannot be fully separated from nuclear arms control or broader economic and national security issues. Space security should be included where relevant in other security conversations, and any discussion of space security proposals should be examined for their impact on other domains. For example, potential bans on ASAT weapons testing or deployment of co-orbital ASAT weapons are likely to have impacts on missile defense. Difficult decisions will need to be made on how to balance the benefits and consequences of limiting all countries’ abilities to pursue certain space technologies or conduct certain space activities that could have negative consequences for everyone.

The U.S. approach toward meeting disruptions to the security and stability of space has focused almost exclusively on an offensive counterspace capability build-up and, to a lesser extent, mixed messaging about intent and deterrence. It is time that all possible options to bolster U.S. national security in space and international strategic stability were fully explored. For this to happen, the United States has to acknowledge the strategic benefits of a fully holistic approach, begin sketching out what it hopes to achieve with space arms control, and start laying the groundwork for doing a cost-benefit analysis of the options it would be willing to forgo in order to persuade competitors to abandon even bigger threats to the United States.

ENDNOTES

1. Brian Weeden and Victoria Samson, eds., “Global Counterspace Capabilities: An Open Source Assessment,” Secure World Foundation, April 2020, https://swfound.org/media/206970/swf_counterspace2020_electronic_final.pdf.

2. Brian Weeden and Kaila Pfrang, “History of ASAT Tests in Space,” August 6, 2020, https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1e5GtZEzdo6xk41i2_ei3c8jRZDjvP4Xwz3BVsUHwi48/edit#gid=0.

3. U.S. Department of Defense and Office of the U.S. Director of National Intelligence, “National Security Space Strategy: Unclassified Summary,” January 2011, https://archive.defense.gov/home/features/2011/0111_nsss/docs/NationalSecuritySpaceStrategyUnclassified

Summary_Jan2011.pdf; U.S. Department of Defense, “Defense Space Strategy Summary,” June 2020, https://media.defense.gov/2020/Jun/17/2002317391/-1/-1/1/2020_DEFENSE_SPACE_STRATEGY_SUMMARY.PDF.

4. “Outer Space: Militarization, Weaponization, and the Prevention of an Arms Race,” Reaching Critical Will, n.d., https://www.reachingcriticalwill.org/resources/fact-sheets/critical-issues/5448-outer-space (accessed November 9, 2020).

5. “Conference on Disarmament (CD),” Nuclear Threat Initiative, June 26, 2020, https://www.nti.org/learn/treaties-and-regimes/conference-on-disarmament/.

6. Michael Listner and Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, “The 2014 PPWT: A New Draft but With the Same and Different Problems,” The Space Review, August 11, 2014, https://www.thespacereview.com/article/2575/1.

7. “First Committee Approves 11 Drafts Covering Control Over Conventional Arms, Outer Space Security, as United States Withdraws Text on Transparency,” GA/DIS/3642, November 5, 2019, https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/gadis3642.doc.htm.

8. Daniel Porras, “PAROS and STM in the UN: More Than Just Acronym Soup” (presentation, UT Austin/Space Traffic Management conference, February 27, 2019), https://commons.erau.edu/stm/2019/presentations/22/.

9. “Statement by Ambassador Wood: The Threats Posed by Russia and China to Security of the Outer Space Environment,” U.S. Mission to International Organizations in Geneva, August 14, 2019, https://geneva.usmission.gov/2019/08/14/statement-by-ambassador-wood-the-threats-posed-by-russia-and-china-to-security-of-the-outer-space-environment/.

10. Michael Krepon, “Space Code of Conduct Mugged in New York,” ArmsControlWonk.com, August 4, 2015, https://www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/404712/space-code-of-conduct-mugged-in-new-york/.

11. UN General Assembly, “Group of Governmental Experts on Transparency and Confidence-Building Measures in Outer Space Activities: Note by the Secretary-General,” A/68/189, July 29, 2013.

12. 2018 UN Disarmament Commission Working Group II, Secretariat nonpaper, n.d., https://www.un.org/disarmament/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/WG2-secretariat-non-paper-outer-space-TCBMs-FINAL.pdf.

13. UN General Assembly, “Further Practical Measures for the Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space,” A/RES/72/250, January 12, 2018.

14. A version of their finding was leaked, leading some participants to raise concerns about the ability to participate in future groups of governmental experts.

15. “The UN COPUOS Guidelines for the Long-Term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities,” Secure World Foundation, November 2019, https://swfound.org/media/206891/swf_un_copuos_lts_guidelines_fact_sheet_november-2019-1.pdf. Secure World Foundation Executive Director Peter Martinez served as the working group chair for these discussions prior to joining the foundation.

16. “UK Push for Landmark UN Resolution to Agree Responsible Behaviour in Space,” UK Foreign Office, August 26, 2020, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-push-for-landmark-un-resolution-to-agree-responsible-behaviour-in-space.

17. “Sending 14 Drafts to General Assembly, First Committee Defeats Motion Questioning Its Competence to Approve One Aimed at Tackling Outer Space Threats,” GA/DIS/3657, November 4, 2020, https://www.un.org/press/en/2020/gadis3657.doc.htm. For a breakdown of the votes of the resolution’s paragraphs, see Reaching Critical Will, Twitter thread, November 6, 2020, https://twitter.com/RCW_/status/1324745999361822721?s=20.

18. Brian Head, “Wicked Problems in Public Policy,” Public Policy, Vol. 3, No. 2 (January 2008): 101-118.

19. The lone exception was the national space policy issued by the George W. Bush administration on August 31, 2006. See “U.S. National Space Policy,” n.d., https://aerospace.org/sites/default/files/policy_archives/Natl%20Space%20Policy%20fact%20sheet%2031Aug06.pdf.

20. “National Space Policy of the United States of America,” June 28, 2010, p. 7, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/national_space_policy_6-28-10.pdf.

21. Weeden and Pfrang, “History of ASAT Tests in Space.”

22. Michael P. Gleason and Peter L. Hays, “A Roadmap for Assessing Space Weapons,” Center for Space Policy and Strategy, October 2020, https://aerospace.org/sites/default/files/2020-10/Gleason-Hays_SpaceWeapons_20201005_1.pdf.

23. U.S. Space Command Public Affairs Office, “Russia Conducts Space-Based Anti-Satellite Weapons Test,” July 23, 2020, https://www.spacecom.mil/MEDIA/NEWS-ARTICLES/Article/2285098/russia-conducts-space-based-anti-satellite-weapons-test/.

24. For further information, see Kaitlyn Johnson, “A Balance of Instability: Effects of a Direct-Ascent Anti-Satellite Weapons Ban on Nuclear Stability,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 21, 2020, http://defense360.csis.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/2Kaitlyn_A-Balance-of-Instability.pdf. She notes that “[w]hile a direct-ascent [anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons] ban may reinforce stability in the space domain—and potentially other domains such as air, land, and sea—it may destabilize the nuclear domain because China and Russia view direct-ascent ASAT weapons as assurance of their nuclear arsenals’ success against U.S. missile defense systems.” Ibid., p. 11.

25. Michael Listner, “A Bilateral Approach From Maritime Law to Prevent Incidents in Space,” The Space Review, February 16, 2009, https://www.thespacereview.com/article/1309/1.

Victoria Samson is the Washington office director and Brian Weeden is the director for program planning at the Secure World Foundation, a nonprofit foundation dedicated to the long-term sustainability of space for benefits on Earth.