"[Arms Control Today] has become indispensable! I think it is the combination of the critical period we are in and the quality of the product. I found myself reading the May issue from cover to cover."

U.S. Questions Russian CTBT Compliance

July/August 2019

By Daryl G. Kimball

A top U.S. intelligence official publicly accused Russia in May of not complying with the 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), raising concerns that the Trump administration may be considering withdrawing from another multilateral arms control agreement. The allegation is a significant shift from recent U.S. government and intelligence community assessments.

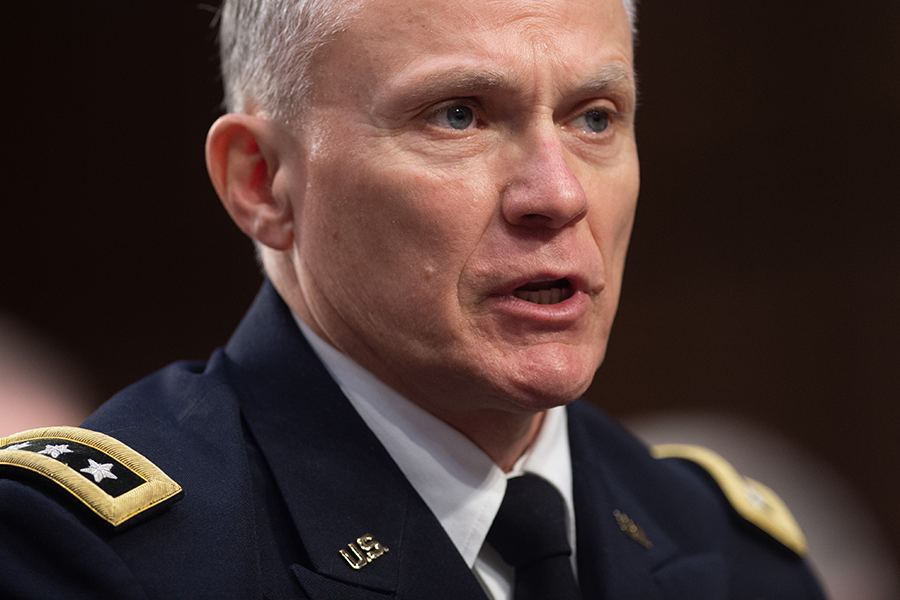

“Russia probably is not adhering to its nuclear testing moratorium in a manner consistent with the ‘zero-yield’ standard” outlined in the CTBT, said Lt. Gen. Robert Ashley, the director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), in remarks to the Hudson Institute May 29.

“Russia probably is not adhering to its nuclear testing moratorium in a manner consistent with the ‘zero-yield’ standard” outlined in the CTBT, said Lt. Gen. Robert Ashley, the director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), in remarks to the Hudson Institute May 29.

Article I of the treaty requires its parties “not to carry out any nuclear weapon test explosion or any other nuclear explosion,” and the issues of low-yield, zero-yield, and subcritical tests were debated at length during the treaty’s negotiation.

The new allegation veers from recent U.S. assessments. In December 2015, for example, Rose Gottemoeller, undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, told the House Armed Services Committee that “within this century, the only state that has tested nuclear weapons...in a way that produced a nuclear yield is North Korea.” More recently, no charge of a Russian CTBT violation was made in the State Department’s annual compliance report released in April.

The allegation raises a number of key questions and poses significant new challenges for states that support the CTBT, including how the Trump administration plans to address the compliance concern and whether officials believe low-yield nuclear explosions to be militarily significant.

Following the charges, some Republican U.S. senators urged the administration to remove the United States from the list of 184 signatories of the treaty, an action that President Donald Trump’s national security adviser, John Bolton, once advocated when he held a senior State Department position in 2002. Whether the Trump administration will seek to exit the CTBT, which it has already said it does not support, is not yet clear. Unlike Russia, the United States has not ratified the pact, a step needed for the treaty to enter into force.

Ambiguous Charges

Asked by a journalist at the Hudson Institute briefing if Russian officials have only “set up at their test site at Novaya Zemlya in such a way that they could conduct experiments in excess of a zero-yield ban in the CTBT” or have actually conducted nuclear test explosions, Ashley said only that Russia had the “capability” to conduct very low-yield supercritical nuclear tests in contravention of the treaty.

He also implied that China may not be complying with the CTBT, saying that “China’s lack of transparency on their nuclear testing activities raises questions as to whether China could achieve such progress without activities inconsistent” with the treaty. He did not provide any evidence that China has violated the treaty.

A White House official sought to clarify Ashley’s comments later at the same event. “I think General Ashley was clear,” said Tim Morrison, senior director for weapons of mass destruction and biodefense at the National Security Council. “We believe Russia has taken actions to improve its nuclear weapons capabilities that run counter or contrary to its own statements regarding the scope of its obligations under the treaty.”

Responding to a flurry of inquiries sparked by Ashley’s comment, the DIA said in a statement June 13, “The U.S. government, including the intelligence community, has assessed that Russia has conducted nuclear weapons tests that have created nuclear yield.”

This statement did not clarify whether the assessment is a joint intelligence community assessment, how much confidence the community has in the assessment, or if the charge is based on very recent intelligence findings or is a new interpretation of older intelligence.

Russia, which signed the CTBT in 1996 and ratified it in 2000, has vigorously denied the allegation. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov called the accusation “a crude provocation” and pointed to the U.S. failure to ratify the treaty. “We are acting in full and absolute accordance with the treaty ratified by Moscow and in full accordance with our unilateral moratorium on nuclear tests,” he said on June 12.

Treaty Status and Verification

The United States signed the CTBT the day it opened for signature in 1996, but the Senate declined to provide its advice and consent for ratification in 1999 after a short and highly partisan debate. In 2009, President Barack Obama said his administration would pursue reconsideration of the pact, but he concentrated early arms control efforts on the negotiation and ratification of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. By 2012, Republicans regained control of the Senate, making CTBT ratification unlikely.

To enter into force, the treaty requires ratifications from 44 specific states, and eight of those (China, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, and the United States) have still not taken that step. Nevertheless, the treaty has established a de facto global moratorium on nuclear testing; and the treaty’s verification tools, the International Monitoring System (IMS) and the International Data Center, have been completed and are fully operational.

The treaty drafters anticipated that the pact would need additional means to detect and deter violations, particularly involving nuclear test explosions at very low yields. If and when the treaty formally enters into force, a state-party may request a short-notice, on-site inspection to investigate a possible violation. The request can be based on information collected by the IMS or through national technical means. Such inspections require the approval of at least 30 members of the treaty’s 51-nation Executive Council, which must decide on inspection requests within 96 hours. An inspection team would arrive at the suspected nation within six days of the council’s receipt of the inspection request.

Under Article VI of the treaty, which addresses the settlement of disputes before or after entry into force, “the parties concerned shall consult together with a view to the expeditious settlement of the dispute by negotiation or by other peaceful means of the parties’ choice, including recourse to appropriate organs of this treaty.” Such measures could involve mutual confidence-building visits to U.S. and Russian test sites by technical experts to address compliance concerns.

‘Zero-Yield’

The DIA assessment that “Russia probably is not adhering” to the CTBT echoes longtime charges by test ban opponents that Russia does not share the U.S. interpretation of what the treaty prohibits and may be conducting extremely low-yield nuclear tests in a containment structure at its Soviet-era nuclear test site on the arctic island of Novaya Zemlya.

In his May 29 remarks, Ashley said the DIA assessment was partly based on the view that Russia “has not affirmed the language of zero yield.” This assertion contradicts State Department fact sheets published in 2011 that report that Russia and all other nuclear-weapon states recognized by the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) have publicly affirmed the CTBT prohibition on all nuclear test explosions, no matter the yield.

“At the time the treaty opened for signature, all parties understood that the treaty was a ‘zero-yield’ treaty as advocated by the United States in the negotiations,” according to a September 2011 publication from the State Department’s Bureau of Arms Control, Verification and Compliance.

“The United States led the efforts to ensure the treaty was a ‘zero-yield’ treaty, after the parties had negotiated for years over possible low levels of testing that might be allowed under the agreement,” according to the document. “Public statements by national leaders confirmed that all parties understood that the CTBT was and is, in fact, a ‘zero-yield’ treaty.”

Under this zero-yield interpretation, supercritical hydronuclear tests, which produce a self-sustaining fission chain reaction, are banned by the treaty. Subcritical hydrodynamic experiments, which do not produce a self-sustaining fission chain reaction, are permitted.

Stephen Ledogar, chief U.S. negotiator of the CTBT, testified to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Oct. 7, 1999, that Russia and the rest of the NPT nuclear-weapon states had committed themselves to the zero-yield standard.

For example, a March 1996 statement from Sha Zukang, the lead CTBT negotiator for China, said that “the Chinese delegation proposed at the outset of the negotiations its scope text prohibiting any nuclear-weapon test explosion which releases nuclear energy.” The future CTBT, he said, “will without any threshold prohibit any nuclear-weapon test explosion.”

More recently, Russia has publicly reaffirmed its commitment to this standard. On July 29, 2009, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev said that, “under the global ban on nuclear tests, we can only use computer-assisted simulations to ensure the reliability of Russia’s nuclear deterrent.”

In an April 2017 essay, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov wrote that the treaty “prohibits ‘any nuclear weapon test explosion or any other nuclear explosion,’ anywhere on Earth, whatever the yield.” Ashley said at the Hudson Institute event that he was not aware of Ryabkov’s essay.

‘Unsigning’ the Treaty

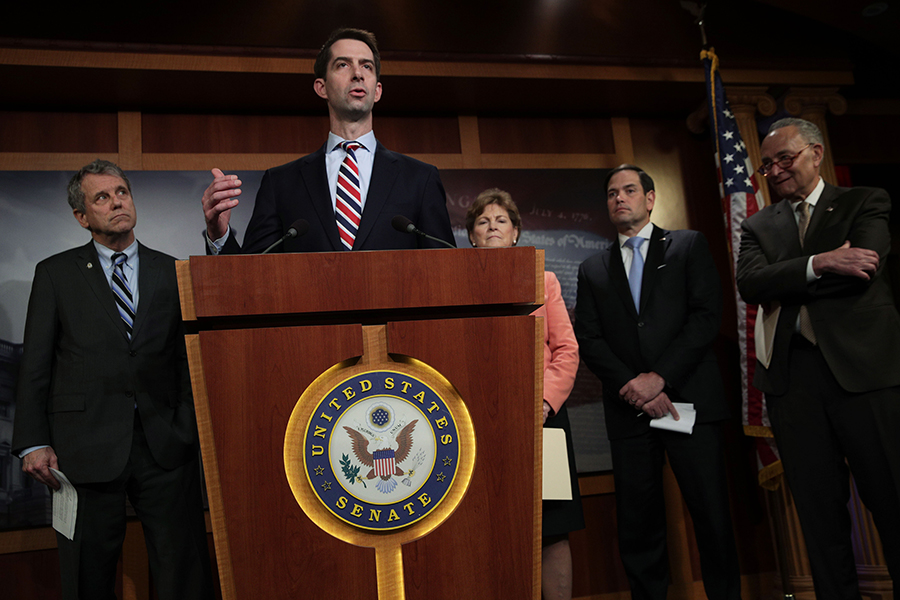

Republican Sens. Tom Cotton (Ark.), Marco Rubio (Fla.), John Cornyn (Texas), and James Lankford (Okla.) sent a letter in March to Trump asking him whether he would consider “un-signing” the CTBT, The Washington Post reported June 13.

If the United States were to formally withdraw its signature from the treaty, it would lose access to the nuclear test monitoring provided by the IMS, consisting of more than 300 seismic, hydroacoustic, infrasound, and radionuclide sensor stations.

If the United States were to formally withdraw its signature from the treaty, it would lose access to the nuclear test monitoring provided by the IMS, consisting of more than 300 seismic, hydroacoustic, infrasound, and radionuclide sensor stations.

According to the Trump administration’s 2017 budget request, the United States “receives the data the IMS provides, which is an important supplement to U.S. National Technical Means to monitor for nuclear explosions (a mission carried out by the U.S. Air Force). A reduction in IMS capability could deprive the U.S. of an irreplaceable source of nuclear explosion monitoring data.”

According to CTBT rules, only treaty signatories can access IMS monitoring information, and only treaty signatories have voting rights in meetings of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization.

A decision by the Trump administration to formally exit the CTBT would lead to international condemnation. In November 2018, the UN General Assembly overwhelmingly adopted a resolution on the CTBT that “urges all states that have not yet signed or ratified, or that have signed but not yet ratified...to sign and ratify it as soon as possible.” The resolution was approved 183-1 with four abstentions. Only North Korea, whose recent nuclear tests were condemned in the resolution, voted against the resolution. The United States abstained.