This past October, Undersecretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Rose Gottemoeller visited several states where the United States conducted some of the 1,030 nuclear weapons test explosion before the end of nuclear weapons testing in September 1992.

Her mission: to speak about the enduring value of the 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT)—which the United States was the first to sign but is still among the last few that has not yet ratified.

Undersecretary Gottemoeller’s tour did not begin and end in Nevada, where the United States conducted 921 nuclear test explosions, including 100 above-ground tests, beginning in 1951, and ending with the last U.S. nuclear test in September 1992.

Instead, Gottemoeller’s trip included stops in Alaska and Colorado—where the United States also conducted nuclear test explosions, and in Utah, which suffered from the downwind effects of atmospheric nuclear testing in Nevada—to deliver remarks on nuclear testing and the CTBT.

Between Oct. 19-30, Gottemoeller spoke across the country, in Fairbanks, Anchorage, Denver, Colorado Springs, Salt Lake City and Provo. Earlier this year she also announced she would travel to New Mexico and Mississippi, where the United States also conducted nuclear tests.

Alaska: The Largest Underground Test

On Oct. 19, Gottemoeller visited the University of Alaska at Fairbanks to deliver remarks on nuclear testing and the CTBT.

The Aleutian Island chain in Alaska was the site of three nuclear test blasts: the 80 kiloton Long Shot test on October 29, 1965, the 1 megaton Milrow test, on Oct. 2, 1969, and the nearly 5 megaton Cannikan on Nov. 6, 1971.

The Cannikin blast on Amchitka Island was the largest, and among the most controversial, underground nuclear test explosion in U.S. history. The detonation was designed to test a missile warhead for the "Safeguard Anti-Ballistic Missile system that was scrapped just four years later.

The Guardian reported at the time that “When President Nixon canvassed the opinion of seven Government agencies his own Office of Science and Technology pointed out that the test was of only marginal technical usefulness. Of the seven agencies canvassed only two, the US Atomic Energy Commission and the Department of Defence, expressed approval.”

The Cannikin bomb was detonated in a 50-foot diameter chamber at the bottom of a 6,000 foot deep shaft. The massive force of the explosion lifted the ground over a wide area just above the blast, as shown in this video.

In July 1971, the Committee for Nuclear Responsibility filed suit against the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), petitioning the courts to stop the test. The case went to the Supreme Court, which denied the injunction by a vote of 4 to 3, opening the way for the test to go ahead.

Cannikin also triggered the very first Greenpeace voyage in 1971 from Vancouver, Canada in an attempt to stop the test from happening.

Today, concerns remain about the long-term risk of radioactive leakage from the Cannikan test and the site is the subject of ongoing research and monitoring for signs of contamination.

Colorado’s “Nuclear Fracking” Experiment

Part the United States nuclear weapons test program was designed to investigate so-called “peaceful” uses for nuclear explosions. Under the Operation Plowshare program, the United States detonated 35 “Peaceful Nuclear Explosions” (PNEs), which have, along with all other nuclear test explosions, been banned by the CTBT. Colorado was the site of two Ploughshares nuclear test explosions: the Rulison test outside of Grand Valley, and the Rio Blanco test near Rifle, on Sept. 10, 1969 and May 17, 1973, respectively.

The Colorado tests were a joint government and industry gas stimulation experiment to explore the possibility of using nuclear explosions to extract natural gas for commercial use. While the experiments were marginally successful in extracting the natural gas, the gas was too radioactive to be used or sold commercially. Rio Blanco was the last nuclear test in the Operation Plowshare program.

Photographer Kelly Michals’s online photo album below shows what the Rulison test site looks like today, and also includes historical pictures documenting the preparations for, the protests against, and the equipment and warhead used in the Rulison nuclear test.

Downwind Utah

Victims of geography, the prevailing winds, and Cold War secrecy, the people of southern Utah suffered from the 100 atmospheric nuclear weapon test explosions conducted at the Nevada Test Site, but information about the problem was suppressed for years. At first, local residents saw the testing in Nevada as necessary and safe. Then, as they began to feel the direct impacts of the fallout, attitudes began to change.

The 1953 Upshot-Knothole nuclear test series from March 17 until June 4 produced several high-fallout events that deposited radioactive debris on the downwind towns.

Ranchers reported burns on their animals' faces and lips where they had been eating radioactive grass, and large numbers of miscarriages. As many as a quarter of the herds in southern Utah and Nevada died. Concerned about possible adverse public reaction, the AEC issued a press release attributing the deaths to ''unprecedented cold weather.''

Ranchers and preliminary veterinary investigators suspected radiation poisoning. The AEC sent teams of radiation experts to examine ailing animals and reportedlyforced its scientists to rewrite their field reports and eliminate any references about radiation damage or effects.

By the mid-1950s, leukemia and other radiation-caused cancers appeared in residents of Utah, Arizona, and Nevada living in areas where nuclear fallout had occurred and the incidence of childhood leukemia rose in certain areas by the late-1950s.

In the late-1970s, Utah governor Scott Matheson helped raise public awareness on the effects of nuclear testing on downwinders in Utah. In a series of congressional hearings in 1979, he presented evidence of the adverse health effects of the tests and the AEC’s obfuscation. The efforts led to wider research on the effects of the test fallout nationwide.

In 1990 Congress approved and President George H. W. Bush signed into law the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, which created a $100 million trust fund to compensate downwinders in certain areas who contracted certain radiation-related diseases.

The legislation states in part: "The United States should recognize and assume responsibility for the harm done to these individuals. And Congress recognizes that the lives and health of uranium miners and of innocent individuals who lived downwind from the Nevada tests were involuntarily subjected to increased risk of injury and disease to serve the national security interests of the United States. The Congress apologizes on behalf of the Nation to the individuals...and their families for the hardship they have endured."

“Atomic Mississippi”

A half century ago, the state of Mississippi was ground zero in the struggle for civil rights, as well as the only U.S. nuclear weapons tests east of the Rocky Mountains.

Mississippi’s Tatum Salt Dome in rural Lamar County near Hattiesburg was the site of two nuclear test explosions in the mid-1960s. The Salmon test on Oct. 22, 1964 and the Sterling test on Dec. 3, 1966 were conducted to help determine whether and how nuclear test yields could be disguised through "decoupling" and how well such blasts could be detected.

The AEC used the 5.3-kiloton Salmon nuclear test to create a cavity, and then executed the 380-ton Sterling test to see if the shockwaves would be muffled.

Residents in the immediate vicinity of the nuclear test site were given $10 per adult and $5 per child as an “inconvenience” reimbursement for having to relocate for the day of the Salmon test, but later reported that the damage was more significant than what they were initially led to believe, including property damage or water wells going dry.

In 2010, the Energy Department transferred surface ownership of the Salmon site to the Mississippi state government so that "the site could be used as a wildlife refuge and working demonstration forest," according to a Energy Department fact sheet. The Energy Department retains the rights to the subsurface of the Salmon site property and will continue the scheduled monitoring of surface water and groundwater, which remains at risk from contamination from the underground blast chamber.

Dr. Stephen Cresswell of West Virginia Wesleyan College writes on reactions from the public to the nuclear tests in his article, “Nuclear Blasts in Mississippi.”

Earlier this year, a group of University of Mississippi journalism students released a 30-minute documentary film, "Atomic Mississippi" that takes a look back at the tests 50 years later with interviews of residents from surrounding communities. Read more on that here.

New Mexico’s Forgotten Downwinders

New Mexico was the site of three nuclear tests, including the first every U.S. test, code-named Trinity, and the Plowshare program Gnome and Gasbuggy tests of Dec. 10, 1961 and Dec. 10, 1967.

Trinity was a 21-kiloton test explosion of a plutonium device of the same type that would be detonated over Nagasaki only a few weeks later and would kill an estimated 140,000 people by 1950.

Conducted at 5:29 am on July 16, 1945, the test produced a yield equivalent to about 21,000 tons of TNT and created a blinding light that was so bright it was visible nearly 200 miles away. Upon seeing the Trinity blast, the director of the Manhattan Project that designed and developed the bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer, said it brought to mind a passage from the Hindu scripture, Bhagavad-Gita:

“If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once in the sky,

that would be like the splendor of the Mighty One.

I am become Death, the shatterer of Worlds”

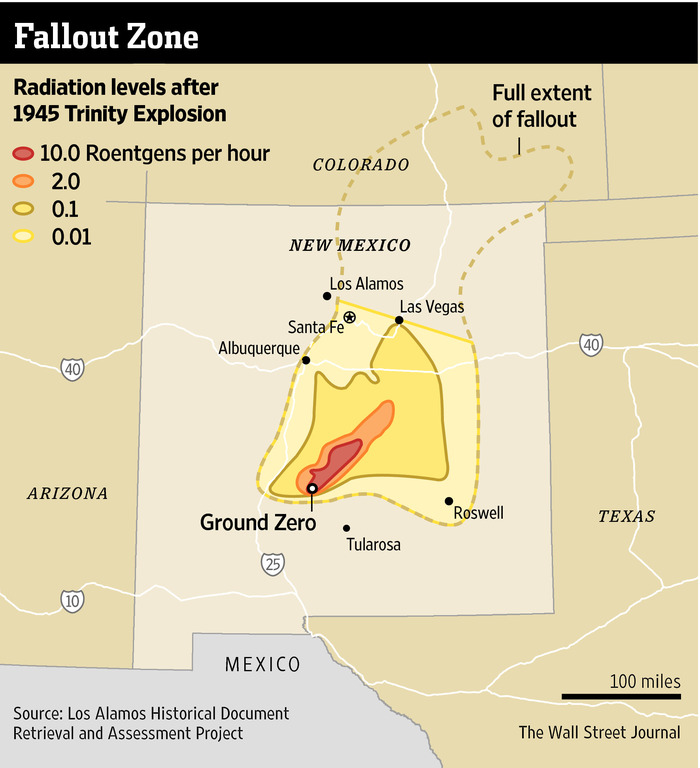

The explosion produced a cloud of radioactive debris that rose to 35,000 feet and moved northeastward. To this day, the environmental and health impacts of the fallout from the Trinity explosion are still not well understood.

Last year, the federal government launched a new study to investigate the effects of the fallout on New Mexicans. As The Wall Street Journal reported last fall, investigators with the National Cancer Institute have begun a new, in-depth study of people who lived in the state at the time of the Trinity test to help assess the doses and the effects of consuming food, milk and water that were likely contaminated by the explosion.

Last year, the federal government launched a new study to investigate the effects of the fallout on New Mexicans. As The Wall Street Journal reported last fall, investigators with the National Cancer Institute have begun a new, in-depth study of people who lived in the state at the time of the Trinity test to help assess the doses and the effects of consuming food, milk and water that were likely contaminated by the explosion.

The new study could eventually help lead to the inclusion of New Mexico’s downwinders in the 1990 Radiation Exposure Compensation Act program. Sen. Tom Udall (D-N.M.) has been pushing to make Trinity "downwinders" eligible for the program, but has so far been unsuccessful.

Never Again

The age of nuclear testing may be over, but the effects of nuclear testing are still taking a toll in the United States—and in other areas of the world subjected to nuclear testing—remain.

In 1983 the National Cancer Institute began a study that was not made public until 1997 that found that millions of children across the country, particularly in several fallout hot-spots, were exposed to large amounts of radioactive iodine (I-131), mostly by drinking milk contaminated with fallout from 90 of the largest above-ground nuclear bomb testing in Nevada in the 1950's and 60's. People who are now 50 years of age or older, particularly those born between 1936 and 1963 and who were children at the time of testing, are at higher risk for thyroid cancer.

The study estimates that the larger amounts of I-131 from the Nevada test site fell over some parts of Utah, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, and Montana, but I-131 traveled to all states, particularly those in the Midwestern, Eastern, and Northeastern United States. Results of the study are available online.

In addition to providing the medical monitoring and support that downwinders, nuclear test veterans, and cleanup workers deserve, one of the important ways to honor their sacrifice will be to ensure a permanent end to all nuclear weapons testing, everywhere, through the CTBT.

As Undersecretary Gottemoeller said in her Fairbanks, Alaska talk on Oct. 19, the stories and the experience of the downwinders of nuclear testing and the survivors of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki “… are a critically important reminder that all nations should avoid the horrors of nuclear war. For all of these people, the CTBT is not just a piece of paper, it is a guarantee that no one will have to experience what they have experienced.”

—DARYL G. KIMBALL AND SHERVIN TAHERAN