"I find hope in the work of long-established groups such as the Arms Control Association...[and] I find hope in younger anti-nuclear activists and the movement around the world to formally ban the bomb."

What Wargames Reveal About Expanding the U.S. Nuclear Arsenal

October 2025

By Matthew Cancian

In recent years, the United States has embarked on a modernization of its nuclear weapons arsenal that is projected to cost upward of $540 billion for acquisition alone.1 Nevertheless, there is a growing chorus of experts, defense contractors, and politicians who want to go bigger. Recent analyses by such groups as the Heritage Foundation, the Atlantic Council, and the 2023 Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States make the case for an increase in the quantity and variety of U.S. nuclear weapons.2 Their vision goes beyond the long-delayed nuclear modernization program that is already underway; these nuclear hawks want the U.S. president to have even more warheads and more tactical nuclear options to use in any prospective great-power war.3

Despite such arguments, President Joe Biden and now President Donald Trump seem to believe the current nuclear arsenal is sufficient. Their judgments are supported by 15 iterations of a U.S.-China wargame set in 2028, which found that U.S. nuclear superiority did not factor into the deterrence calculations of Chinese teams and that the United States did not benefit from launching damage-limiting first strikes with its superior arsenal.4 Expanding the arsenal would divert funding from strengthening U.S. conventional deterrence, would make U.S. nuclear use more likely, and threaten to start an unlimited arms race instead of moving toward arms control.

Presidential Skepticism

Successive U.S. presidents have been skeptical about nuclear expansion. President Joe Biden argued that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.”5 His national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, more explicitly tied this view to quantitative limitations: “I want to be clear here: The United States does not need to increase our nuclear forces to outnumber the combined total of our competitors in order to successfully deter them.”6 Despite having radically different policies from Biden on so many issues, President Donald Trump expressed a similar idea: “There’s no reason for us to be building brand-new nuclear weapons; we already have so many.”7 So, who’s right? The nuclear hawks or the presidents?

A series of wargames conducted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology supported the presidents against the recommendations of the nuclear hawks. To examine the causes and consequences of deterrence failures, our team modified a previous U.S.-China wargame to include nuclear weapons and ran it 15 times.8 Each iteration had different members of the U.S. national security community as participants, with members of the intelligence community playing China. Despite the varied composition of teams, U.S. nuclear superiority and counterforce capabilities had no impact on the decisions of the China teams’ decision-making.

Among the seven China teams that recommended and used nuclear weapons, all recognized the extreme risk of such a choice, knowing that the United States could inflict catastrophic damage.9 However, the scale of potential devastation—whether from 300 or 1,000 U.S. warheads—did not alter the teams’ willingness to proceed. Furthermore, no U.S. team believed that it lacked tactical nuclear options sufficient to retaliate against Chinese nuclear attacks, if it so chose. Therefore, the study found no evidence that expanding the U.S. nuclear arsenal quantitatively or qualitatively would have enhanced deterrence.

The wargaming exercise strongly suggests that the United States should embrace the continuity between Biden and Trump by resisting the urge to expand the size and diversity of its nuclear arsenal. To dissuade China from gambling for resurrection—by using nuclear weapons to salvage a failing conventional campaign—during a future war, U.S. diplomacy will be more important than nuclear threats.10 Expanding the U.S. nuclear arsenal is not only wasteful because it would divert U.S. funding from strengthening its conventional deterrence; it is also dangerous because it makes U.S. first use of nuclear weapons more likely and shifts diplomacy toward an unconstrained arms race.11 The United States must be prepared to successfully prosecute a high-end conventional war while at the same time providing face-saving offramps to the adversary to avert a nuclear conflict that would be damaging to all sides. Following presidential wisdom not expanding the nuclear weapons is the way to do this.

Nuclear Superiority vs. Nuclear Sufficiency

Separate from the kinds of nuclear weapons that are built is the question of quantity: Does nuclear superiority provide more deterrence, or is sufficiency all that matters?

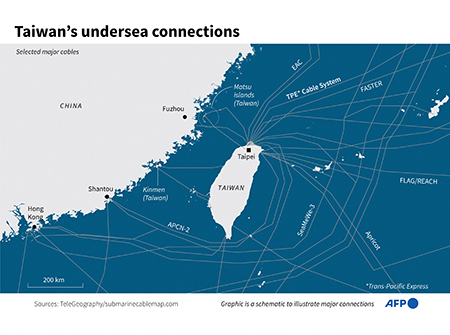

The return of great-power competition, with the potential for great-power war, has raised the specter of the United States having to deter two nuclear adversaries, China and Russia. Russia seemed on the verge of using nuclear weapons in the October 2022 crisis, when it suffered dramatic battlefield defeats in Ukraine.12 Such worries have continued, for example in light of President Vladimir Putin codifying changes to Russia’s nuclear doctrine in November 2024 to broaden the range of nuclear employment scenarios.13 Meanwhile, China has been expanding its nuclear arsenal against a backdrop of increasing concerns about a possible invasion of Taiwan.14 This has led some analysts to conclude that if nuclear weapons are becoming more salient and U.S. adversaries are acquiring more of them, then surely the United States also needs to expand its force size to maintain deterrence.15

The argument that U.S. nuclear superiority leads to improved deterrence is superficially intuitive and has some scholarly support. One proponent of this concept argues that a larger nuclear arsenal means that, in retaliation to an adversary’s first strike, more U.S. weapons would penetrate an adversary’s defenses, more cities would be struck, and more people would be killed in a countervalue attack.16 A larger number of nuclear weapons would also be helpful in a disarming nuclear first strike on an adversary.17

According to the authors of the 2023 Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States, expansion of the U.S. arsenal is needed to, “Address the larger number of targets due to the growing Chinese nuclear threat.”18 Thus, an expanded arsenal theoretically offers benefits both under a counterforce (targeting an enemy’s nuclear weapons) or countervalue (targeting an enemy’s civilian population) nuclear strategy. Meanwhile, Vipin Narang and Pranay Vaddi raise the specter of coordinated action by the Russians, Chinese, and/or North Koreans to justify their advocacy of “more, different, and better nuclear capabilities.”19

However, there are also theoretical reasons why nuclear sufficiency, not relative capabilities, matter for deterrence. Although the early days of the Cold War were characterized by a headlong rush toward more capability, U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower’s Air Force secretary saw past this to an age when any nuclear war would be “an unthinkable catastrophe for both sides.”20 In theoretical terms, as long as a country possesses a secure second strike, the magnitude of that second strike is not consequential for deterrence. In a counter to proponents of nuclear expansion, other contemporary scholars have proposed that the United States should embrace nuclear sufficiency despite Russia’s saber-rattling and China’s buildup.21

A first step in adjudicating nuclear superiority and sufficiency is to imagine how these concepts would play out in a real-world situation. Imagine two different worlds with illustrative numbers in which there is a 2027 war between China and the United States. In the first world, the United States has maintained current nuclear force levels. Following a countervalue logic, this “limited” force could deliver one nuclear weapon to each of the 100 largest Chinese cities while maintaining a similar reserve capability against Russia. Alternatively, following a counterforce logic, the United States could strike first to limit damage from China, such that the 100 largest U.S. cities would be struck by Chinese retaliation. In the alternate world, the United States has a larger arsenal: Now it can strike the 200 largest Chinese cities while maintaining a reserve capability, or it could launch a nuclear first strike against China so that only the 50 largest U.S. cities would be struck in a Chinese nuclear retaliation.

Would China be more deterred from nuclear escalation in the counterfactual world where the United States has a larger arsenal than in the world where the United States maintains its current arsenal size? There are certainly measurable differences—in the millions of deaths on both sides—between the two worlds. However, just because something is measurable does not mean that it is significant. It is possible that quantitative differences in nuclear arsenals could have no influence on nuclear deterrence, as long as both sides have sufficient arsenals. Historic cases give some insight, but differences in coding can lead to differences in findings. Another methodological possibility is wargaming.22

Wargames Support a Strategy of Nuclear Sufficiency

To explore the drivers and consequences of deterrence failures during the U.S. military’s pacing scenario—a war against China during a Taiwan invasion in 2028—my co-authors and I modified added nuclear posturing and use to our existing wargame and ran it 15 times.23 Previous wargames have mostly either ended at nuclear use or investigated the results of scripted nuclear use, rather than allowing players to choose nuclear use and then navigate its consequences.24 Chapter 4 of the report contains a more complete description of methodology. It is important to note here that the project focused on understanding the military logic of using nuclear weapons in a Taiwan scenario and did not address the likelihood of their actual use. Political factors were minimized by defining players as operational commanders, but some players still considered political aspects, such as the international reputational costs of breaking the nuclear taboo. The frequency of nuclear-weapon use in the game iterations did not reflect their probability in real conflict, as political leaders might use nuclear weapons differently or act as a brake against their use due to fears of escalation and moral opprobrium.

These 15 games produced the full gamut of nuclear scenarios, underlining the inherent unpredictability of nuclear escalation. Some China teams opened the games with a High-altitude Electro-Magnetic Pulse (HEMP) nuclear weapon. Other times no team used any nuclear weapons, successfully concluding with a ceasefire. However, many games saw nuclear use beyond HEMP. Although this sometimes led to ceasefires, in other scenarios it also led to escalatory spirals that ended in a global conflagration.

The clearest risk of nuclear first use came from a China team that believed that its invasion was failing and wanted to gamble for resurrection. Before reaching this critical decision, China teams experienced great initial successes in establishing a beachhead on Taiwan but faced increasing setbacks. Over time, the Chinese amphibious fleet suffered heavy losses, and logistical support dwindled, causing a decline in Chinese combat power on the island. By weeks three to five, with supplies inadequate and no functioning captured port or airfield, defeat loomed, forcing the China teams to choose between an adverse settlement, likely defeat, or the use of nuclear weapons.

U.S. quantitative nuclear superiority was understood by the China teams, but it did not deter them. All teams recognized that the United States maintained an advantage in the nuclear domain despite the significant growth of the nuclear inventories of China’s People’s Liberation Army in the decade leading up to 2028.25 As occurred in other wargames, the China teams were aware that using nuclear weapons could provoke U.S. retaliation. They noted that the United States had more escalatory options and the capability to launch a damage-limiting counterforce strike against China.26 However, they believed that as long as the United States could not execute a disarming counterforce strike, strategic nuclear attacks were unlikely. Thus, U.S. nuclear superiority was not a primary factor in the Chinese calculations, and the China teams that chose not to use nuclear weapons were influenced by factors other than their nuclear inferiority.

Similarly, the China teams did not consider the magnitude of U.S. countervalue retaliation as an important factor in deterrence. This is in line with Robert Jervis’s theory of the nuclear revolution. According to Jervis, the possession of a few nuclear weapons by a state is sufficient to deter an adversary, regardless of whether the adversary possesses a larger arsenal.27 The logic behind this is that the destructive power of nuclear weapons is so immense that even a small number can inflict unacceptable damage, rendering the exact number of weapons less significant. Therefore, states are not deterred by the adversary’s larger nuclear arsenal because the mutual threat of destruction, inherent in even a limited number of nuclear weapons, ensures deterrence.

Nor did U.S. teams realize any benefits from launching damage-limiting nuclear first strikes against China’s nuclear forces. In the two games where Chinese nuclear forces were subjected to large damage-limiting nuclear attacks, the China teams maintained enough nuclear capability to launch counterattacks on the U.S. homeland. They withstood the U.S. counterforce attack and used their remaining mobile intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) to achieve a favorable outcome in both games (after destroying several U.S. cities in a process of Schellingesque nuclear bargaining).28 Consequently, counterforce attacks on China did not provide U.S. teams with decisive war-winning advantages.

Even a U.S. nuclear buildup would be unable to achieve the first-strike capability that proponents envision, absent an exquisite penetration of Chinese command and control networks. China’s development and deployment of mobile ICBMs are critical in granting the country a credible second-strike capability. These missiles are mounted on mobile launch platforms, allowing them to be transported and hidden across various terrains, making it difficult for adversaries to track and target them. The mobility of these ICBMs enhances China’s second-strike capability, ensuring that it can retaliate even if its fixed nuclear sites are compromised in a first strike. Additionally, China’s development of advanced missile technologies, including multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles, further bolsters the effectiveness and survivability of its mobile ICBM force. Furthermore, China could simply build more of these systems as they see the United States building up its own nuclear forces in a quixotic pursuit of a disarming first strike. All of this ignores the moral questions, global outcry, and severe political repercussions that would be entailed by a nuclear first strike.

The Illogic of Nuclear Warfighting

In addition to advocating for more nuclear weapons writ large, many nuclear hawks also want increased diversity of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons. Much of the debate has focused on the nuclear-capable, sea-launched cruise missile, which was forced on the Biden administration by Congress.29 But the call is broader, with a recent article advocating for the United States to acquire more “non-strategic nuclear weapons” to match Russian and Chinese capabilities.30 This would entail procuring not only medium range ballistic missiles such as the Russian Iskander-M or the Chinese DF-21, but also the Russian Kalibr-class cruise missiles and even the Poseidon underwater drone.31

It is unclear, however, how more diverse weapons would help the United States in either deterring or fighting a nuclear war. Matching the nuclear delivery means of all potential adversaries would be difficult and would not guarantee symmetric effects. For instance, although a U.S. Iskander-class weapon based in NATO countries could reach key cities in Russia, Russian Iskanders cannot reach U.S. territory (exactly as was the case in the Cold War). Symmetry of technology and delivery profile does not equate to symmetry of effects.

In the series of wargames featuring scenarios on nuclear escalation in Taiwan, there was no point when participants believed that a Chinese nuclear attack with medium-range ballistic missiles would not elicit a U.S. response because the United States could only respond with air-launched cruise missiles, gravity bombs, and silo-launched or submarine-launched ICBMs. Even if a Russian or Chinese leader believed that a nuclear first strike would not elicit a U.S. response because the United States lacked a missile with a corresponding flight pattern, that would be a slender reed on which to embark on a potentially cataclysmic action.

Moreover, if nuclear warfighting with China or Russia is envisaged, there is no clear ceiling on how many nuclear weapons would be needed. A point often made by nuclear hawks is that nuclear weapons individually are not as destructive as commonly portrayed.32 This is certainly true. However, it would be almost impossible to gain the “ability to destroy sufficient levels of opponents’ fielded military forces and associated support infrastructure such that they are unable to operate effectively on the field of battle, therefore leaving one free to impose one’s political will upon opponents or force them to accept a cessation of hostilities,” as assessed by one nuclear weapons advocacy paper.33 This approach would envision the ability to launch thousands of nuclear attacks on Chinese or Russian ground forces, dispersed as they are in large territories.

In the wargames, the only time that the United States was able to successfully retaliate against China’s nuclear first use was with limited employment against a small target set. (Eight warheads were required to completely neutralize the Chinese ground forces on Taiwan during that game according to the models that we constructed using data provided by our sponsor.) In this iteration, China launched a nuclear attack against Taiwanese ground forces. With the nuclear forces in the current U.S. program of record, the United States had several options for delivering a limited counterblow against the Chinese ground forces on Taiwan. This led to both sides accepting a status quo ante peace, albeit in a world that would be changed profoundly in ways that cannot be modeled, and that would certainly be worse than if both parties had reached a negotiated settlement before nuclear use.

Finally, a focus on nuclear warfighting detracts from the primary utility of nuclear weapons: bargaining. In the wargames, the most successful outcomes came from diplomacy backed by nuclear force, not from battlefield employment. Perhaps looking at the results of exercises such as Carte Blanche, Schelling concluded that, “The adequacy of our nuclear weapons in Europe is not determined by whether we could win a full-scale European nuclear campaign…. Their function is to make the triggering of inadvertent or pre-emptive war a frighteningly probable consequence of their large-scale use or of a massive nuclear effort to destroy them.”34

The ability of the wargames to escalate to nuclear use—all the way up to a global nuclear conflagration—surprised not only players, but also the study’s authors. Juxtaposing that with the nuclear hawks’ desire to “impose one’s political will” makes the disconnect between political theory and the advocacy for battlefield nuclear weapons clear.

However, if the maxim, ceteris paribus—more options are better than fewer—is true, why not acquire more nuclear weapons and more varying types? These wargames do not cover all conceivable scenarios. Many players on the U.S. team pointed to concerns about Russia when weighing their nuclear responses to China. If more nuclear options do not help in the U.S. pacing scenario, why not acquire them on the chance that they are useful in other scenarios?

Wasteful and Dangerous

There are three ways in which acquiring additional nuclear weapons would be actively harmful: by diverting money from conventional arms, by increasing the temptation for U.S. nuclear first use, and by damaging the prospects for arms control discussions.

It is crucial to invest in conventional weapons such as bombers, submarines, and long-range anti-ship missiles to deter China from starting a conflict in the first place. U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth emphasized the importance of funding conventional warfighting capabilities as one of his priorities.35 The Strategic Posture Review explicitly states that it did not conduct a cost analysis when recommending nuclear expansion, but any meaningful expansion would severely impact conventional warfighting. The wargames demonstrate the danger of China miscalculating its ability to conquer Taiwan rapidly, as Putin did in Ukraine.36 Increasing U.S. conventional capabilities rather than nuclear arms would make such a miscalculation less likely.

The growing discussions of U.S. nuclear first use in a Taiwan scenario also highlight the danger that increasing the U.S. arsenal would make U.S. nuclear first use more likely. There is a large literature on how bureaucracies shape the decisions of U.S. presidents in crisis, from the Cuban missile crisis to President Barack Obama’s Afghanistan surge.37 Having built a nuclear “hammer,” the national security bureaucracy would feel the need to justify that expenditure by finding a “nail.” There is a risk that, during a war with China, some element of the bureaucracy would be able to convince a U.S. president that nuclear first use would lead to a successful outcome. Although U.S. first use never paid off in the wargames, it is possible that it might; however, the U.S. president should not make decisions based on wishful thinking.

Finally, U.S. nuclear expansion would jeopardize future arms control discussions with China. China’s nuclear strategy is highly sensitive to U.S. capabilities; any significant enhancement of the U.S. nuclear arsenal may prompt China to expand its own nuclear forces to ensure a credible deterrent.38 This dynamic can escalate tensions and make arms control negotiations more challenging.39 Furthermore, acknowledging the mutual vulnerability of China and the United States to nuclear attack is a key to any nuclear negotiations with China.40

A U.S. nuclear buildup could diminish trust and reduce the incentives for both sides to engage in arms control agreements. Admittedly, China’s interest in negotiations has been tepid, as was its response to Trump’s desire to reduce the global nuclear arsenal.41 However, there are areas on which progress could be made.42 Furthermore, given the consequences of failure, any negotiating effort is worth making, especially when that effort simply entails not wasting tens or hundreds of billions of dollars on unnecessary nuclear weapons.

ENDNOTES

1. Xiaodon Liang, “U.S. Nuclear Modernization Programs,” Arms Control Association, August 2024.

2. For examples, see: Greg Weaver and Amy Woolf, “Requirements for Nuclear Deterrence and Arms Control in a Two-Peer Nuclear Peer Environment,” Atlantic Council, February 2, 2024; Robert Peters, “Nuclear Posture Review: The Next Administration Building the Nuclear Arsenal for the 21st Century,” The Heritage Foundation, July 30, 2024; and Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States, “America’s Strategic Posture: The Final Report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States,” U.S. Congress, October 2023.

3. For an early warning about the delayed nuclear modernization, see Mackenzie Eaglen and Kingston Reif, “The Ticking Nuclear Budget Time Bomb,” War on the Rocks, October 25, 2018.

4. For the report, see: Mark Cancian, Matthew Cancian, and Eric Heginbotham, “Confronting Armageddon: Wargaming Nuclear Deterrence and Its Failures in a U.S.–China Conflict over Taiwan,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 13, 2024.

5. President Joe Biden, “Joint Statement of the Leaders of the Five Nuclear-Weapon States on Preventing Nuclear War and Avoiding Arms Races,” The White House, January 3, 2022.

6. “Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan,” presented at the Arms Control Association Annual Forum, The White House, June 2, 2023.

7. President Donald Trump’s remarks to press on February 13, 2025, published on YouTube by ABC News, “Trump: There’s no reason for us to be building brand new nuclear weapons,” February 13, 2025.

8. For the original project on conventional invasion, see Mark F. Cancian, Matthew Cancian, and Eric Heginbotham, “The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 9, 2023.

9. It should be noted that the Chinese themselves are less inclined to countenance nuclear use in a war with the United States over Taiwan. See Fiona S. Cunningham and M. Taylor Fravel, “Dangerous Confidence? Chinese Views on Nuclear Escalation,” International Security Vol. 44, No. 2 (October 1, 2019): pp. 61-109. This point was reiterated by Tong Zhao during the CSIS rollout event for the wargames report. Matthew Cancian, moderator, “Confronting Armageddon: Wargaming Nuclear Deterrence and Its Failures in a U.S.-China Conflict over Taiwan,” panel discussion with Kari Bingen, Charles Glaser, and Tong Zhao, Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 13, 2024.

10. The role of diplomacy and politics in discussions of military scenarios is often overlooked. For a treatment of other political factors in the Taiwan scenario, see: Matthew F. Cancian, “States of Denial: Sensibly Defending Taiwan,” in Survival: April-May 2025, edited by the International Institute for Strategic Studies, Routledge, 2025, p. 25.

11. Daryl G. Kimball, “Why We Must Reject Calls for a U.S. Nuclear Buildup.” Arms Control Today Vol. 53, No. 9 (November 2023): p. 3.

12. Lachlan Mackenzie, “Six Days in October: Russia’s Dirty Bomb Signaling and the Return of Nuclear Crises,” Center for Strategic and International Studies. September 4, 2024.

13. For a fuller discussion of Russian nuclear signaling, see: Anya L. Fink, “Russia’s Nuclear and Coercive Signaling During the War in Ukraine.” Congressional Research Service, November 26, 2024.

14. The most recent China Military Power Report covers this nuclear expansion in greater detail than previous reports. See: U.S. Department of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2024,” December 18, 2024.

15. Most explicitly, see Matthew Kroenig, “Washington Must Prepare for War With Both Russia and China.” Foreign Policy, November 15, 2024.

16. Matthew Kroenig, The Logic of American Nuclear Strategy: Why Strategic Superiority Matters, New York: Oxford University Press, 2020.

17. Although nuclear expansion advocates never say that the aim of nuclear expansion is to improve the U.S. capability to launch a damage-limiting first strike, a damage-limiting second strike is paradoxical and the United States does not have a countervalue nuclear doctrine. Thus, advocates of nuclear expansion use phrases like “hold at risk” adversary nuclear forces. For example, see: Patty-Jane Geller, “China’s Nuclear Expansion and Its Implications for U.S. Strategy and Security,” The Heritage Foundation, September 14, 2022.

18. Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States, 2023.

19. Vipin Narang and Pranay Vaddi, “How to Survive the New Nuclear Age,” Foreign Affairs, June 24, 2025.

20. I.F. Stone, “Nixon and the Arms Race: How Much Is Sufficiency?” The New York Review of Books, March 27, 1969.

21. Charles L. Glaser, James M. Acton, and Steve Fetter, “The U.S. Nuclear Arsenal Can Deter Both China and Russia,” Foreign Affairs, October 5, 2023.

22. Introduction by James Goldgeier in Mathew Fuhrmann and Diane Labrosse, eds., “Roundtable 10-25 on The Logic of American Nuclear Strategy: Why Strategic Superiority Matters,” Robert Jervis International Security Studies Forum, H-Diplo | ISSF Roundtable, Volume X, No. 25 (2019).

24. See, Stacie Pettyjohn, Becca Wasser, and Chris Dougherty, Dangerous Straits: Wargaming a Future Conflict with Taiwan (Washington, DC: CNAS, 2022); Stacie Pettyjohn and Hannah Dennis, Avoiding the Brink: Escalation Management in a War to Defend Taiwan (Washington, DC: CNAS, February 2023), ; David Shullman, John Culver, Kitsch Liao, and Samantha Wong, Adapting US Strategy to Account for China’s Transformation into a Peer Nuclear Power. Atlantic Council, 2024; Andrew Metrick, Philip Sheers, and Stacie Pettyjohn. Over the Brink: Escalation Management in a Protracted War, Center for New American Security, 2024.

25. A fact acknowledged even by nuclear hawks. See “China’s Emergence as a Second Nuclear Peer: Implications for U.S. Nuclear Deterrence Strategy,” Study group convened by the Center for Global Security Research at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, March 14, 2023; Greg Weaver and Amy Woolf, “Requirements for Nuclear Deterrence and Arms Control in a Two-Peer Nuclear Peer Environment,” Atlantic Council, February 2, 2024.

26. Andrew Metrick, Philip Sheers, and Stacie Pettyjohn, “Over the Brink: Escalation Management in a Protracted War,” Center for a New American Security, August 6, 2024.

27. Although the term was not coined by Jervis, his remains the canonical text on its interpretation. See Robert Jervis, The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution: Statecraft and the Prospect of Armageddon, Cornell University Press, 1989.

28. “Paper Prepared by Thomas C. Schelling,” in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961-1963, Volume XIV, Berlin Crisis, 1961-1962, Document 56, U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian, July 5, 1961.

29. Xiaodon Liang, “U.S. Starts Work on Nuclear-Capable Missile,” Arms Control Today, July/August 2024.

30. Charles Richard, Franklin Miller, and Robert Peters, “Nuclear Deterrence vs. Nuclear Warfighting: Is There a Difference and Does It Matter?” The National Institute for Public Policy, No. 623, April 15, 2025.

31. Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight-Boyle, “Russian nuclear weapons, 2024,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 80, No. 2 (March 7, 2024): pp. 118-45.

32. Tim Goorley, “Nuclear Weapons Options and Effects,” Presented at the Materials Science in Extreme Environments, John Hopkins University, March 12, 2024.

33. Richard, Miller, and Peters, 2025.

34. Carte Blanche saw 355 simulated atomic bomb uses in a NATO-Soviet war. See Der Spiegel, “Überholt wie Pfeil und Bogen,” July 12, 1955. For the Schelling quotation, see Schelling, 1961.

35. David Vergun, “Pentagon Prioritizes Homeland Defense, Warfighting, Slashing Wasteful Spending” DOD News, U.S. Department of Defense, February 9, 2025.

36. Mark F. Cancian, “Putin’s Invasion Was Immoral, Not Irrational,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 10, 2022.

37. For an early discussion of the role of bureaucratic politics in the Cuban Missile Crisis, see Graham T. Allison, “Conceptual Models and the Cuban Missile Crisis,” The American Political Science Review, Vol. 63, No. 3 (September 1969): pp. 689-718. On the surge, see Kevin Marsh, “Obama’s Surge: A Bureaucratic Politics Analysis of the Decision to Order a Troop Surge in the Afghanistan War,” Foreign Policy Analysis, Vol. 10, No. 3 (2014): pp. 265-288.

38. As has occurred in the past. See Joanne Tompkins, “How U.S. Strategic Policy Is Changing China’s Nuclear Plans.” Arms Control Today, January 2003.

39. Tong Zhao, “Dangerous Parallax: Chinese-U.S. Nuclear Risks in Trump’s Second Term,” Arms Control Today, December 2024.

40. David Santoro, ed., “US-China Mutual Vulnerability Perspectives on the Debate,” Pacific Forum, Issues & Insights, Vol. 22, SR2, May 2022.

41. “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Guo Jiakun’s Regular Press Conference on February 14, 2025,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China.

42. Tong Zhao, “Underlying Challenges and Near-Term Opportunities for Engaging China,” Arms Control Today, January/February 2024.