Beyond Oppenheimer: Nuclear Weapons in U.S. Popular Media

June 2024

By Luisa Kenausis

In recent years, nuclear weapons have made their way back to a prominent role in popular media in the United States. The headliner has been Oppenheimer, the most feted film of the 2024 Academy Awards and the most high-profile movie depicting nuclear weapons in decades. Beyond that example, nuclear weapons have appeared repeatedly in other U.S. media products, playing roles of varying significance in fictional movies, TV and streaming series, and docuseries and documentaries.

Nuclear weapons are not a new element in cinematic culture in the United States, but it seems they are more of a focus today than they have in a generation. To understand the surge in interest, viewers must consider the societal function of storytelling, the interaction of global politics and popular culture, and the history of nuclear weapons in pop culture.It is also necessary to examine some recent and upcoming nuclear weapons-related films and TV shows, assess how they interact with prevailing Western narratives about nuclear weapons, and consider their potential impact on public opinion on nuclear weapons in the United States.

Narrative and Popular Media

Storytelling is how humans preserve and share knowledge. When a story is shared with people, its imbued meaning can be spread widely and become part of a community’s common beliefs or knowledge. In this way, stories allow people to make sense collectively of the world around them.1

Over time, the stories that people see and hear repeatedly, especially in a popular culture context, can contribute to their worldview and become part of a shared cultural perspective. The ways that objects such as nuclear weapons are depicted in popular, typically fictional TV shows and films and the narratives that are linked to them through popular media impact how the real-life versions of those objects are perceived and discussed within a culture.

Although global events can drive trends in popular culture, interaction between the two phenomena is more complex. Popular media informs the way that global events are perceived and interpreted within a specific cultural context.2 Pop culture is produced and consumed intertextually, with viewers, consciously or not, interpreting popular films and TV shows in relation to other popular works that they have already seen or that have already entered cultural consciousness. One fictional depiction of nuclear weapons may not drastically change a viewer’s personal beliefs about those weapons, but the viewer’s preexisting beliefs about nuclear weapons likely have been shaped by nuclear-related narratives that have been repeated across U.S. popular media over time.

U.S. Nuclear Cinema From 1950 to 1990

Popular films tend to reflect the beliefs, fears, and pervasive questions of their time. Within just a few years of the first nuclear detonations in 1945, U.S. filmmakers were using their films to examine nuclear weapons and nuclear war and its potentially apocalyptic aftermath thoughtfully. When public views on nuclear weapons shifted over time in response to global events, the depiction of nuclear weapons shifted as well, leading to a few distinct eras in nuclear cinema in the United States.3

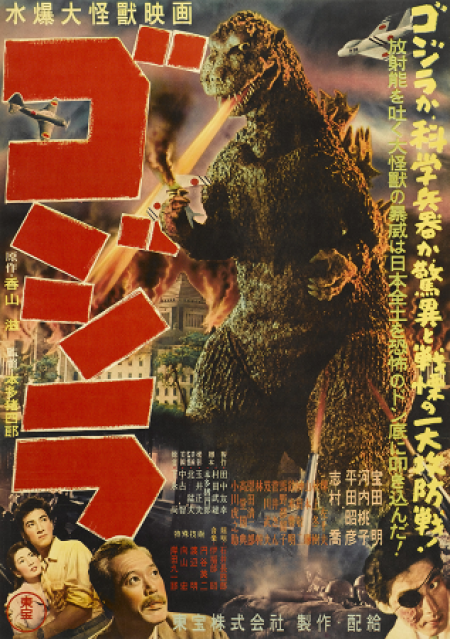

Early films about nuclear weapons took seriously the task of making sense of these new weapons. Their narratives often felt heavy with anxiety, fear, and guilt, reflecting the nation’s complicated feelings about the bomb. The first Soviet nuclear test in 1949 and subsequent nuclear arms race further drove nuclear fears in the United States. In the 1950s, radiation-based monster and mutant movies reflected growing fears about the unknown impacts of radiation, nuclear testing, and atomic fallout.4 Science fiction films such as Godzilla, King of the Monsters! released in the United States in 1956 in a heavily modified version from the original Japanese Godzilla, Them!5 in 1954, and The Incredible Shrinking Man in 1957 emphasized the unknown, unpredictable dangers posed by nuclear weapons. In the same period, films such as On the Beach, released in 1959 and set in 1964, offered direct warnings to audiences that a nuclear war could lead to the extinction of humanity in the near future.6 These films raised questions about the atomic bomb and its effects, and their narratives centered on the unknown, potentially uncontrollable destructive power of nuclear weapons.

A few years later, Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb in 1964 took a sharper look at the dangers posed not only by the physical power of nuclear weapons, but also by reliance on nuclear deterrence to prevent a doomsday scenario. In this film, nuclear weapons are not depicted as a source of strength or protection for the nation holding them but as a vulnerability at the global level.

While the Cold War thawed from the late 1960s to 1979, nuclear weapons played relatively little role in U.S. films. This shifted following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980. A series of crises in the early 1980s, along with Reagan’s “axis of evil” speech in March 1983, again stoked fears of nuclear war among the U.S. public.7 These heightened fears were reflected in The Day After, a 1983 ABC TV movie in which nuclear war breaks out between the United States and the Soviet Union, destroying Lawrence, Kansas. Nuclear narratives in The Day After are reminiscent of those from the early nuclear films, with emphasis placed on the unimaginable horrors of a nuclear attack and its aftermath and the human impact of nuclear explosions.

Since the Cold War ended, the role of nuclear weapons in films has been reduced significantly, with weapons often functioning as plot devices rather than as film topics in themselves. In the 1996 blockbuster Independence Day, for example, the United States launches a nuclear-armed missile at an alien spaceship hovering above Houston, and the missile destroys the city but fails to harm the spaceship. In this film, the primary purpose of nuclear weapons is to demonstrate the alien ship’s imperviousness to human technology. No clear message about nuclear weapons themselves can be discerned from the film.

Nuclear War Rebooted

One consequence of the complex relationship between global political events and popular culture is that a viewer’s specific experience with a particular work of popular media is dependent on when and where they see it, with their viewing context being informed by current events in the world and their local news cycle. In February 2024, an audit analyzing U.S. media coverage of nuclear weapons between August 2020 and August 2023 found that coverage increased sharply following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, from a prewar average of 500 stories per month to a peak of nearly 3,000 stories in March 2022.8 After that, nuclear weapons coverage appears to track with key events in the Russian-Ukrainian war and threatening statements from Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Across the analyzed coverage, there appear to be broadly shared assumptions among journalists, officials, and other quoted sources that nuclear weapons are dangerous and that their use would be catastrophic and must be avoided. Perspectives diverge, however, on the question of how best to avoid nuclear war. Proponents of arms control characterize nuclear weapons as a source of risk and advocate for their reduction or elimination in order to prevent nuclear war. Those in the other camp characterize a strong nuclear arsenal as essential to deter attack. These perspectives constitute the two competing narratives about nuclear weapons in today’s media: nuclear weapons keep the world safe or put us at risk.

In recent months, there has been significant media attention paid not only to specific news events relating to nuclear weapons, but to the rising risk of nuclear war more broadly. In March 2024, The New York Times launched “At the Brink,” an interactive multimedia series that seeks to examine the current dangers posed by nuclear weapons and consider what can be done to reduce nuclear risks. In the first installment, a narrative essay is paired with interactive illustration, animation, photography, video, and audio to depict vividly a hypothetical nuclear attack.9 Five installments have been published so far, and the series is expected to run through 2024.10

A recent public opinion survey further illuminates the context in which the current wave of nuclear weapons media will be interpreted. In the survey, respondents report relatively low familiarity with nuclear weapons topics, but six in 10 of them indicate interest in learning more about nuclear weapons and U.S. nuclear weapons policy.11 The survey was conducted a year after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and five months before the premiere of Oppenheimer, making it a useful snapshot of public opinion at this nuclear moment in film and TV.

The Current Wave

The much-anticipated release of Oppenheimer in July 2023 marked the start of the current surge of nuclear weapons in popular media. Directed by Christopher Nolan, the film tells the story of physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer and his role in the creation of the atomic bomb. Although most of the film focuses on the Manhattan Project, it also depicts a contentious 1954 congressional hearing on the renewal of Oppenheimer’s security clearance.

The film uses debates among Oppenheimer and other scientists to raise some of the competing narratives about nuclear weapons. As the Manhattan Project progresses, viewers see scientists discuss whether the new weapon will make the world more or less safe, whether the bomb should be used against a nearly defeated Japan, and whether the United States should pursue development of a hydrogen bomb. Although these on-screen debates add some nuance, the primary narrative is that before the United States used nuclear weapons against Japan, its creators believed that atomic bombs would mean the end of war. In an early scene, Niels Bohr asks Oppenheimer, somewhat leadingly, if the weapon will be big enough to end “all” war. Later, Oppenheimer repeats this belief directly more than once, saying that the bomb “will ensure a peace mankind has never seen” and that after it is used, “nuclear war, maybe all war, becomes unthinkable.” Notably, his view changes dramatically by the end of the film, but his post-Hiroshima perspective on the bombs is less explored.

Oppenheimer has drawn criticism for not giving a voice to the victims of nuclear weapons.12 Although the number of Japanese people killed by the atomic bombings is mentioned, the movie does not show the use of the bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki or the physical effects of the weapons on the human victims. Moreover, in telling the story of the Manhattan Project and the first U.S. nuclear test, called Trinity, Oppenheimer makes no mention of the downwinders, the victims of the fallout from U.S. nuclear testing. Nolan has said that the film does not show the bombings of Japan to maintain its subjectivity because Oppenheimer himself did not witness them and the film extends from Oppenheimer’s point of view.13 This omission may strengthen the film as a portrayal of Oppenheimer, but by leaving out the ugliest and most horrific consequences of nuclear weapons, it limits its own potential to inform its audience on nuclear weapons.

In some recent releases, nuclear weapons exist in the background. In Wes Anderson’s 2023 movie Asteroid City, for example, the film takes place in an isolated desert town, bursting with atomic kitsch imagery reminiscent of 1950s Americana. Characters comment idly on the atomic bomb tests that go off every so often. Despite the obvious proximity of nuclear weapons to Asteroid City, it is difficult to say what statement, if any, the film is trying to make about them.

Amazon Prime’s new streaming science fiction series Fallout, based on the video game franchise, reflects a similar tendency. The Fallout games are known for raising complex questions about nuclear weapons14 and, at times, offering a surprisingly accurate and powerful portrayal of a nuclear attack. In the new series, nuclear weapons serve only to explain the postapocalyptic setting in which the story takes place, and their portrayal lacks realism. In the first scene, viewers see a large-scale nuclear attack on Los Angeles, but the explosive flashes are weak, the shock waves move impossibly slowly, and the scale of destruction per detonation is far too small.15 The series explores stories in a wasteland created by a massive nuclear war, but real-world questions and concerns about nuclear weapons feel out of scope.

Fictional and dramatized films can increase viewers’ interest in nuclear weapons, but leave out key information when it does not fit the narrative of the story being told. Recent and upcoming documentaries can build on this increased awareness and allow interested viewers to learn more about the reality of nuclear weapons.

Netflix’s Turning Point: The Bomb and the Cold War is a nine-part nonfiction docuseries that looks at the development of the atomic bomb and the ensuing rapid proliferation of nuclear weapons. It links the collapse of the Soviet Union to the history of the Cold War to Putin’s ascent to power and ultimately to the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. Nuclear weapons are particularly relevant in the first episode, which focuses on the U.S. effort to develop the atomic bomb during World War II and the decision to use it against Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

There is overlap between the timelines depicted in Oppenheimer and Turning Point, but the two productions differ sharply in that Turning Point tells the story with a focus on the victims of the bomb, including victims of nuclear testing in the United States. For example, in Turning Point, viewers learn how a girls dance camp was located only 40 miles from the Trinity test site and how all but one of the 12 girls there would die of cancer before turning 30 years old. In Oppenheimer, these girls and other downwinder victims are not addressed at all.

Turning Point continues to challenge and interrogate commonly held notions about nuclear weapons. When the narrative that using atomic bombs against Japan was militarily necessary in order to end World War II is raised, most experts interviewed challenge or flat out reject it, arguing that the decision to use the atomic bomb was driven more by concerns about the balance of power with the Soviet Union than actual military imperative. The same episode features interviews with several Japanese hibakusha as they share their memories of the atomic bombing, another group of nuclear weapons victims essentially ignored in Oppenheimer.

Upcoming Documentaries

Looking forward, a flurry of new documentaries and the seriousness with which they promise to address nuclear weapons could mark a meaningful shift in nuclear cinema. First We Bombed New Mexico draws attention to the downwinders of New Mexico who have been harmed by the testing of nuclear weapons near their communities. The film profiles Tina Cordova, leader and co-founder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium and a cancer survivor, in the fight for justice for the many nuclear victims in her state. Directed by Lois Lipman, the film is screening in festivals. Its timing coincides with a legislative effort to renew and expand the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, which originally excluded New Mexicans and is slated to sunset on June 7. The expansion bill passed the U.S. Senate in March, but is stuck in the House of Representatives.16

Bombshell tells the story of the struggle to control the narrative surrounding the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The documentary will examine how the United States fought to repress accurate reporting on the atomic bombings until the publication of John Hersey’s Hiroshima. The film will consider the staying power of narratives and the ways journalists and others can challenge prevailing narratives. Now in production, it is directed by Ben Loeterman.17

Finally, How to Stop a Nuclear War will adapt Daniel Ellsberg’s book The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner into a feature-length documentary that promises not only to inform its audience about the dangers inherent in U.S. nuclear war planning, but also to call the audience to action. In a promotional video, actress Kristen Stewart said the film “sounds the alarm about this threat, but also shows the solutions and steps we can take to avert catastrophe.”18 Directed by Paul Jay, the documentary is in production.

Impact and Trends

The United States may be at the beginning of a wave of pop culture products depicting or discussing nuclear weapons. The earliest and most popular project in this current era, Oppenheimer, was released less than a year ago. It is too soon to draw conclusions about the long-term impact that any of these recent or planned releases will have on public opinion about nuclear weapons, and there are no recent survey data.

Nevertheless, there are some real-time information sources that can inform this question. Reviewing Google Trends data for U.S.-based web searches for “nuclear weapons” over the last few years suggests that people tend to seek information on nuclear weapons immediately following global events that remind them of the risks of nuclear war. In particular, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and Putin’s subsequent nuclear threats have led to spikes in search volume, but other recent film and TV releases that deal with similar topics have not had a similar effect. Despite Oppenheimer’s release in late July, for instance, July and August 2023 did not see a significant uptick in searches on nuclear weapons.19 There was a heavy media buzz leading up to the premiere and a healthy box office turnout, but it appears that watching the film did not spur many viewers to seek further information about nuclear weapons.

Recent and upcoming media projects dealing with nuclear weapons can be grouped into two broad categories, based on content, target audience, and intended impact on the viewer. Several dramatized and fictional properties (Oppenheimer, Fallout, Asteroid City) appeal to a relatively broad audience and aim primarily to entertain audiences. Films and TV shows in this category have the effect of increasing public awareness of nuclear weapons through viewership of the properties themselves and through media coverage surrounding their release, which can have an even bigger impact.20 Yet, these projects are unlikely to move viewers to take action against nuclear weapons because they are meant primarily to entertain.

The other category is nonfictional properties, which often have a narrower audience but can dig deeper into the details of nuclear weapons topics with the primary objective of informing their audience and feeding its curiosity. Since the Cold War, the audience for documentaries and docuseries about nuclear weapons in the United States has been narrow. With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, nuclear weapons unfortunately have returned to salience, offering an unusually potent opportunity to reach viewers through a documentary. The potential audience for nuclear weapons documentaries is large and growing. Most people are interested in learning more about nuclear weapons, and it appears that filmmakers are moving quickly to meet and build on this interest.

Although these recent releases and the Russian war on Ukraine have brought nuclear weapons back into public awareness, it seems likely that the U.S. audience simply does not feel equipped yet to take action. Since the Cold War, most people in the United States have spent little time thinking about nuclear weapons, and an entire younger generation has no memory of the Cold War. As a major blockbuster, Oppenheimer may have raised public awareness of nuclear weapons, but it does not offer viewers a clear understanding of the dangers that these weapons pose or a pathway for viewers to take action against them. The film could increase interest to such a degree, however, that its audience might be more likely to engage with future nuclear weapons documentaries.

In terms of potential audience impact, the documentaries now being readied for release could not come at a better time. Russia’s war on Ukraine has kept nuclear weapons in the headlines, and this topic will continue to feel unusually relevant and salient to the public. The popularity of Oppenheimer may have a priming effect on public interest that bolsters viewership and audience engagement for upcoming anti-nuclear weapons documentaries.

ENDNOTES

1. Lucas M. Bietti, Ottilie Tilston, and Adrian Bangerter, “Storytelling as Adaptive Collective Sensemaking,” Topics in Cognitive Science, Vol. 11, No. 4 (October 2019): 710-732.

2. Jutta Weldes and Christina Rowley, “So, How Does Popular Culture Relate to World Politics?” in Popular Culture and World Politics: Theories, Methods, Pedagogies, ed. Federica Caso and Caitlin Hamilton (Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2015), pp. 11-34.

3. Paul Boyer, “A Life in American Cinema: The Nuclear Option,” Perspectives on History, Vol. 46, No. 8 (November 2008), https://www.historians.org/research-and-publications/perspectives-on-history/november-2008/a-life-in-american-cinema-the-nuclear-option.

4. Toni Perrine, “The Godzilla Factor: Nuclear Testing and Fear of Fallout,” Grand Valley Review, Vol. 16, No. 1 (1997): 19-40.

5. Steve Ryfle, Ed Godziszewski, and Yuuko Honda-Yun, Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, From Godzilla to Kurosawa (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2017), pp. 105-106.

6. Iris Strimitzer, “On the Relationship Between Apocalyptic Films and Reality in U.S. Cold War Culture” (thesis, Universität Graz, April 2021), https://permalink.obvsg.at/UGR/AC16210730.

7. Deron Overpeck, “‘Remember! It’s Only a Movie!’ Expectations and Receptions of The Day After (1983),” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Vol. 32, No. 2 (June 2012): 267-292.

8. Adrienne Lynett, “Arms Control Advocates Have Increased Voiceshare, Media Audit Finds,” ReThink Media, February 12, 2024, https://rethinkmedia.org/blog/arms-control-advocates-have-increased-voiceshare-media-audit-finds.

9. W.J. Hennigan, “The Brink,” The New York Times, March 7, 2024.

10. “New York Times Opinion Announces a New Series on Nuclear Threats,” The New York Times, March 4, 2024.

11. Dina Smeltz, Craig Kafura, and Sharon Weiner, “Majority in U.S. Interested in Boosting Their Nuclear Knowledge,” Chicago Council on Global Affairs and Carnegie Corporation of New York, July 2023, https://globalaffairs.org/sites/default/files/2023-07/Nuclear%20Survey%20Report%20PDF.pdf.

12. Emily Zemler, “Critics Say Omitting the Japanese Toll Makes ‘Oppenheimer’ ‘Morally Half-Formed,’” Los Angeles Times, August 4, 2023.

13. Christian Holub, “Christopher Nolan Responds to Criticism for Not Showing Hiroshima Bombing in Oppenheimer,” Entertainment Weekly, November 8, 2023.

14. Cameron Hunter, “The Ambivalent Nuclear Politics of Fallout Video Games,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, October 17, 2018, https://thebulletin.org/2018/10/the-ambivalent-nuclear-politics-of-fallout-video-games/.

15. Fallout, season 1, episode 1, “The End,” directed by Jonathan Nolan, written by Geneva Robertson-Dworet and Graham Wagner, aired April 10, 2024, on Amazon Prime Video.

16. Danielle Prokop, “RECA Expansion Passes U.S. Senate,” Source New Mexico, March 7, 2024, https://sourcenm.com/2024/03/07/reca-expansion-passes-u-s-senate/.

17. “Bombshell,” Filmmakers Collaborative, n.d., https://filmmakerscollab.org/films/bombshell/ (accessed May 5, 2024). Devon Terrill, a colleague of the author, is a consulting producer on this project.

18. Etan Vlessing, “Kristen Stewart Warns the World Is ‘Dangerously Close’ to Nuclear Catastrophe,” The Hollywood Reporter, December 15, 2023, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/kristen-stewart-nuclear-catastrophe-warning-1235758067/.

19. Use of Google Trends highlighting Google searches from the United States from January 1, 2019, to April 1, 2024, showed spikes in search frequency for the term “nuclear weapons” that closely aligned with nuclear weapons-related global news events.

20. Stanley Feldman and Lee Sigelman, “The Political Impact of Prime-Time Television: ‘The Day After,’” The Journal of Politics, Vol. 47, No. 2 (June 1985): 556-578.