"I find hope in the work of long-established groups such as the Arms Control Association...[and] I find hope in younger anti-nuclear activists and the movement around the world to formally ban the bomb."

Achieving Success Beyond Final Documents: Recommendations for the 2026 NPT Review Conference

May 2024

By Ian Fleming Zhou, Valeriia Hesse, Anna-Elisabeth Schmitz, and Karina Touzinsky

Global tensions are surging with Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, echoing the Cold War era’s geopolitical instability and dangerous nuclear rhetoric.

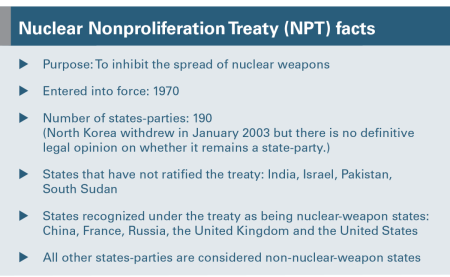

In this environment, the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) review conference scheduled for 2026 will be a juncture for the nuclear nonproliferation regime, demanding a reinvigoration of arms control and multilateral diplomacy amid the continuous erosion of crucial arms control instruments. Otherwise, the continued failure of the review conference process could contribute to several major negative consequences: further erosion of arms control frameworks, expansion of geopolitical tensions, diminished confidence in multilateral diplomacy, and the increased risk of nuclear conflict and nuclear proliferation.

During the review conferences of the 1980s, the international environment was strained and marked by the invasion of Afghanistan, the Iran-Iraq war, and setbacks in arms control negotiations. The lessons learned from these conferences can inform the approach to achieving success in 2026 in a similarly strained geopolitical environment. In particular, analysis of the 1985 review conference can help identify key success factors. This is especially true when considering adept negotiation tactics and the strategic emphasis on incremental achievements to cultivate cooperation in the realm of future nuclear nonproliferation.

Recognizing the pivotal role of multilateral institutions is crucial, given the difficulty in achieving consensus on key issues in today’s global politics.1 Although NPT review conference success seemingly is tied to the adoption of an outcome document achieved by consensus, the current dynamics of geopolitics make reaching such a document nearly impossible. In such circumstances, NPT states-parties become accustomed to not achieving consensus. The result is a stalemate with no further progress toward more effective arms control with clear objectives, confidence- and security-building measures, and adaptability. This raises questions about the efficacy of the existing approach to the NPT negotiations and further emphasizes the urgency of exploring alternative mechanisms to ensure the “success” of NPT review conferences and to foster progress in nonproliferation, disarmament, and peaceful uses of nuclear energy, especially when consensus appears elusive.

Lessons From the Past

The 1980 review conference was marked by unresolved issues and the absence of a final declaration. For instance, the Iran-Iraq war impacted negotiations because Iranians were unwilling ideologically to compromise out of fear of displaying the weakness of their new postrevolution regime. Additionally, the pursuit of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) faced obstacles, with delayed concessions contributing to the breakdown of consensus. Effectively, the United States shifted its stance too late in the process to make a difference.2

During the 1985 review conference, strategic compromises among nations became instrumental to reaching consensus.3 Diplomatic mediation found solutions to stalemates such as the discord between Iran and Iraq. In the final declaration, states-parties condemned attacks on civilian nuclear infrastructure, referring to the attacks on Iraq’s Osirak reactor and Iran’s Bushehr reactor, and agreed to attach Iran’s and Iraq’s statements on the attacks to the final document package. Intentional negotiation pertaining to the CTBT impasse resulted in agreement to disagree: the language acceptable to all parties in addressing the test ban reflected the disagreement by including the statement that “the conference, except for certain states,” regretted that the treaty had not been agreed.4

The success of the 1985 review conference is attributed to various factors. Despite several ongoing crises, tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States were waning, and their new leaders were more inclined to cooperate at the conference.5 In general, the credibility of the NPT hinged on steering clear of consecutive failures and reaching consensus on a final declaration. As a result, member states arrived with a shared determination to secure an outcome document and refrained from directly attacking each other.6 The Soviet Union and the United States had a common interest in preserving a strong nonproliferation norm and recognized that their cooperation would shape the review conference structure and tone.7 Because of this common interest, they were able to compartmentalize NPT-related issues.8

Although at a similarly extreme height of geopolitical tensions among all the key players, the 2026 review conference will experience many differences from the 1980s. The desire to produce a consensus document prevailed in 1985, but at the moment, the two major powers do not share common views on arms control. The polarization between Russian and U.S. interests is eroding the arms control mechanisms that existed in the 1980s. It is unclear whether the NPT holds the same significance for Russia. Its recent actions, such as weaponizing the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant9 and threatening to use nuclear weapons against a non-nuclear-weapon state, run counter to the aims of the NPT. This outright defiance of the NPT’s underlying principles and norms impedes compartmentalization of certain aspects under negotiation within the NPT framework in a manner that was possible in 1985.

In 1985, states-parties invented options for mutual gain to reach consensus and break the stalemate that had led to the failure of the 1980 review conference. The key success lessons from the 1985 conference include the ability to acknowledge dissenting voices while maintaining majority support and to emphasize listening, consulting, and backroom negotiations as a means of fostering deeper mutual understanding. This approach allowed the conference to navigate disagreements without compromising the NPT.10 Applying this approach to the upcoming 2026 review conference would provide for flexible negotiating principles and allow for a wider definition of a successful review conference.

Possible Future Outcomes

The success of review conferences extends beyond consensus; a shared commitment to nonproliferation and negotiation strategies are pivotal. This nuanced understanding of historical challenges sets the stage for policy considerations for a successful 2026 review conference.

In reevaluating approaches to the zones of possible agreement within the context of the NPT, it becomes evident that historical emphasis on achieving a consensus document may limit the scope of the success metrics. Perhaps the most optimal outcome lies not in a document adopted by consensus but in a commitment to transform critical issues into actionable items and an opportunity to deliberate on these matters further.

Bearing this in mind, the traditional pass/fail evaluation paradigm should be challenged. Research suggests that there is a spectrum of outcomes that should encourage flexibility in defining success in 2026. The least favorable outcome of a review conference involves a final document that is weakly phrased and fails to reach consensus. This scenario portends significant negative repercussions, including the potential erosion of the NPT, diminished confidence in multilateral diplomacy, heightened risk of nuclear conflict, and increased nuclear proliferation. Such an outcome would signify a failure of the conference to address pressing issues effectively, thereby exacerbating global nuclear insecurity and undermining efforts toward disarmament and nonproliferation.

Next in line on the favorability scale would be an agreement by consensus on a weakly phrased final document on basic issues, such as the reaffirmation of general principles that fails to address key points of contention or detailed differences among states-parties. This course of action outlines the possibility of a less favorable outcome resulting from consensus on a final document that lacks clarity and strength in addressing crucial matters. Consequently, the document may lack specificity and fail to offer a clear road map for addressing anything of true importance. This deficiency leaves major issues unattended, potentially leading to frustration among participants and undermining trust in multilateral diplomacy.

The next possibility involves a neutral favorable outcome whereby an actionable, strongly phrased draft document is formulated but not adopted by consensus. Instead, parties agree to present negotiation outcomes encapsulating varying perspectives in an information circular. This circular operates independently from the outcome document and serves as an informal mechanism to guide subsequent negotiations. It allows for the delineation of disagreements and issues earmarked for future agreement in different forums or through bilateral discussions and potentially quantifies the support and opposition for specific points if required. This approach maintains transparency, encourages continued dialogue, and provides a framework for addressing contentious issues in subsequent discussions.

A more favorable outcome would be a strongly phrased, actionable outcome document that is adopted by consensus, effectively capturing agreements and disagreements among the parties involved. This document serves as a comprehensive representation of diverse perspectives, facilitating a deeper understanding of the challenges and opportunities within the nonproliferation landscape. By acknowledging and addressing varying viewpoints, this outcome fosters a sense of collaboration and cooperation among stakeholders, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of multilateral efforts toward nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation.

The best outcome would include a unanimously agreed upon outcome document, devoid of any disagreements, that is adopted by consensus. This document comprehensively addresses pertinent issues crucial for the preservation and progressive development of the nonproliferation regime. It incorporates robust language and actionable items, reflecting a commitment to tackle nuclear proliferation challenges effectively. Moreover, this outcome fosters principles of transparency, equality, and inclusivity, underlining a collective dedication to promoting peace and security in the global community.

Taking into account the current geopolitical environment, the optimal course of action, in the absence of a consensus on a substantial draft document that aims to uphold and fortify the NPT regime, would involve creating an information circular. This document, characterized by its nonbinding and informational nature, would explicitly detail points of agreement and disagreement. Its publication would not necessitate a vote due to its purely informative purpose. Simultaneously, it would provide a trajectory for subsequent negotiations, address current issues, and create avenues for bilateral or multilateral exploration of specific aspects in alternative formats.

Charting Success in 2026

Redefining success would allow states-parties to view review conferences as dynamic, systematic endeavors that contribute to the continuous growth and development of global nonproliferation efforts. The outcome declaration, whether or not adopted by consensus, should codify systematically points of convergence and divergent views among states-parties in case the negotiation comes to a stalemate. Inclusion of differences is essential for enhancing the transparency and comprehensiveness of the review process.

By utilizing strong rather than diluted language, the outcome document would ensure meaningful discussions fostering nonproliferation, disarmament, and the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. A clear, detailed codification of differences serves as a valuable resource for policymakers, researchers, and stakeholders, enabling a more thorough examination of the complex dynamics shaping the global nuclear nonproliferation landscape without sacrificing the integrity of the discussions through watered-down language.

Approaching the 2026 review conference, the following flexible negotiation principles should be kept in mind: Separate people from the problem. Understand that individual diplomats represent state positions, which cannot be changed easily, rather than just their personal views. On the one hand, judging from the 1980s experience, personalities can deeply influence the process and outcome of the negotiation. On the other hand, although personal contacts and trust are helpful, they frequently cannot fully change policies.

Focus on interests, not positions. Each position in the negotiation carries the weight of geopolitical considerations and national interests. By directing attention toward underlying motivations, negotiations can tap into shared concerns, and conference participants can achieve better results. Sustaining ongoing dialogues across various levels with a broad spectrum of countries, especially among the states holding opposing positions, can be helpful to understand the complexities and diversities of perspectives involved, encouraging collaborative problem-solving that aligns with the broader interests of the international community.

Invent options for mutual gain. It is most important to emphasize that preserving the NPT and the dialogue is in the common security and development interest. Therefore, NPT members must make review conferences meaningful for mutual gain, which entails avoiding diluted language, talking substance even if it means just pinpointing the divergence in positions, and maintaining principles of equality.

Insist on using objective criteria. Such an approach is helpful in settling differences of interest that involve high costs. The objective framework to guide the review conference negotiation should include the NPT itself, relevant International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) documents, the UN Charter, International Court of Justice decisions, and other applicable international norms. At the same time, it is important to admit that there exist limitations to applying international instruments because they themselves are subject to interpretation and bear no enforcement mechanisms.

In redefining success for the 2026 review conference, it is paramount to embrace flexible negotiating principles that embody the evolving nature of global nonproliferation efforts. A key tenet is the systematic reflection of convergent and divergent viewpoints among states-parties within the proposed outcome document in case of a stalemate. As previously mentioned, a substantive and resolute approach, rather than a diluted consensus document, is the true benchmark of success. A separately drafted information circular that captures the different views of the parties could set the direction for further negotiations. Inclusion of differences enhances transparency and comprehensiveness, providing a valuable resource for policymakers, researchers, and stakeholders.

By clearly articulating the intended progress in these review conferences as well as disagreements without dilution, the document becomes a foundation for constructive engagement and future dialogue while maintaining confidence in multilateral diplomacy and institutions. Approaching the 2026 negotiations, it is crucial to shift the focus from consensus but to maintain strong language, engage in preparatory dialogues, understand state positions and discuss differences, agree to disagree, and ensure knowledge transfer. By inventing options for mutual gain, understanding the distinction between individuals and state positions, focusing on issues that align with shared concerns, and insisting on objective criteria rooted in international norms, the review conference process can foster substantive progress that serves the common security and development interests of the international community.

ENDNOTES

1. Jayantha Dhanapala and Randy Rydell, “Multilateral Diplomacy and the NPT: An Insider’s Account,” UN Institute for Disarmament Research, 2005, https://unidir.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/multilateral-diplomacy-and-the-npt-an-insider-s-account-323.pdf.

2. Lewis A. Dunn, “Perspectives on a Nuclear-Weapon-Free World,” Nuclear Threat Initiative, October 2018, https://www.nti.org/wpcontent/uploads/2021/09/Discussion_Paper-Perspectives.pdf.

3. Kjolv Egeland, “Who Stole Disarmament? History and Nostalgia in Nuclear Abolition Discourse,” International Affairs, Vol. 96, No. 5 (July 2020): 1387-1403.

4. Harald Müller, David Fischer, and Wolfgang Kötter, Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Global Order (Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 1994); Lewis Dunn, video interview with authors, November 13, 2023 (hereinafter Dunn interview); Tariq Rauf, video interview with authors, November 7, 2023 (hereinafter Rauf interview).

5. Gaukhar Mukhatzhanova, video interview with authors, November 8, 2023 (hereinafter Mukhatzhanova interview); Dunn interview; Rauf interview.

6. Jozef Goldblat, ed., Non-proliferation: The Why and the Wherefore (Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis, 1985).

8. Bill Potter, video interview with authors, November 21, 2023; Dunn interview; Rauf interview; Robert Einhorn, video interview with authors, November 24, 2023 (hereinafter Einhorn interview); Mukhatzhanova interview.

9. Gabriela Rosa Hernandez and Daryl Kimball, “Russia Blocks NPT Conference Consensus Over Ukraine,” Arms Control Today, September 2022.

10. Goldblat, Non-proliferation; Dunn interview; Rauf interview; Einhorn interview.

Ian Fleming Zhou is a doctoral candidate at the University of Pretoria. Valeriia Hesse is a researcher at the Odesa Center for Nonproliferation in Ukraine. Anna-Elisabeth Schmitz is a foreign and security policy adviser for a member of the German Parliament. Karina Touzinsky is a military policy analyst for the U.S. Department of Defense. This article is adapted from a policy brief based on research supported by the Arms Control Negotiation Academy (ACONA).