The People the Oppenheimer Film Erased

September 2023

By Chantell L. Murphy

Not a single ponderosa pine can be found in the new film Oppenheimer, about physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer. The locations chosen for the Manhattan Project that he led played a pivotal role in the story of the atomic bomb. Not casting the landscape accurately erases an important detail from the film’s portrayal of the development of the world’s most lethal weapon.

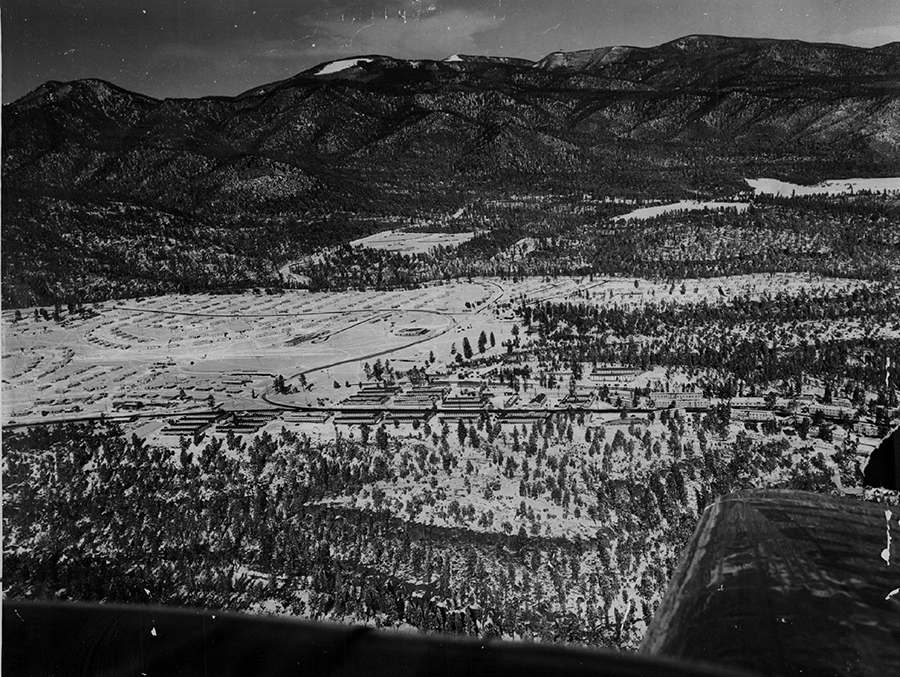

Scientists designed and built the world’s first atomic weapon in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Los Alamos sits on the Pajarito Plateau on the eastern edge of a volcanic complex1 called the Jemez Mountains at an elevation of about 7,500 feet. This is where ponderosa pines tower over Gambel oak and juniper and where the land dramatically drops off into steep basalt cliffs that roll into the Rio Grande River valley below.

Scientists designed and built the world’s first atomic weapon in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Los Alamos sits on the Pajarito Plateau on the eastern edge of a volcanic complex1 called the Jemez Mountains at an elevation of about 7,500 feet. This is where ponderosa pines tower over Gambel oak and juniper and where the land dramatically drops off into steep basalt cliffs that roll into the Rio Grande River valley below.

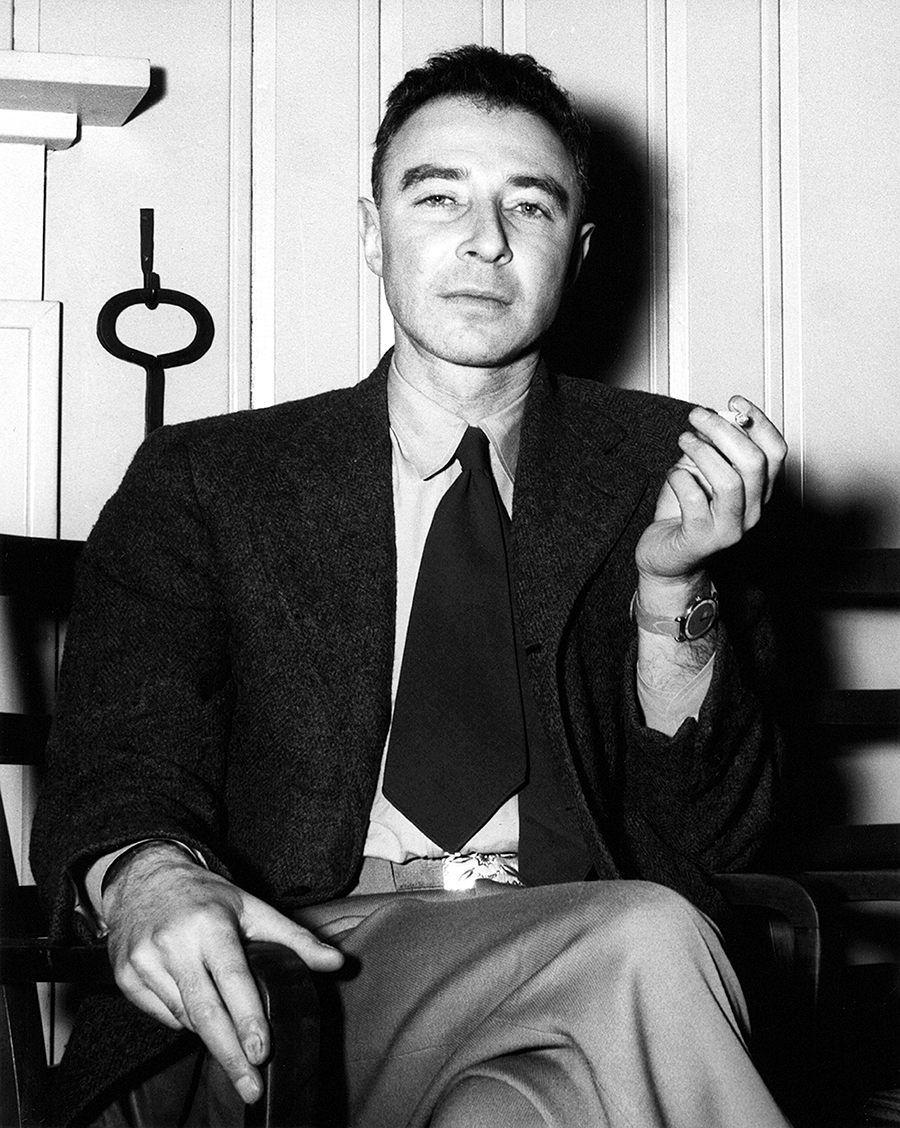

The movie exceeds expectations with its captivating retelling of the events that led to the atomic bomb, including Oppenheimer’s desire for the project to be situated in Los Alamos, but the film failed to capture the reality of the environment and culture that so appealed to him. Director Christopher Nolan and production designer Ruth De Jong made an artistic choice to film exterior scenes at Ghost Ranch in New Mexico instead of Los Alamos to make it look like the “middle of nowhere with nothing around.”2 Instead of pine forest, the Los Alamos scenes are filled with panoramas of open desert, multicolored mesas, and sweeping grasslands.

This decision matters because while beautiful and vast, Ghost Ranch evokes an entirely different feel than the lusher forests around Los Alamos. The environments of Ghost Ranch, drenched in blazing sun and littered with chollas, evoke feelings of exposure and desolation. The film’s landscapes allow the audience to believe that these areas were uninhabited, but in fact, generations of Indigenous and land-based communities have lived on and cultivated Los Alamos for centuries. Selecting Los Alamos as the Manhattan Project site in 1942 forced about 30 native New Mexican families from their land without fair compensation, and many had to abandon their farming equipment, livestock, and animals.3 In Nolan’s portrayal of a singular narrative, the film concealed the environmental and cultural richness of New Mexico that was irrevocably altered by the Manhattan Project through inequitable displacement and the erasure of native voices and culture. Most perniciously, numerous incidences of cancer caused by exposure to radiation from the Trinity Test have persisted over generations and forever have linked New Mexico to the nuclear weapons complex.

When I started working in nuclear nonproliferation at Los Alamos in 2010 as a graduate research assistant, we did not learn about the history of the local and Indigenous communities. We learned about the brilliant male scientists, the excitement of the race to push applied physics to the limit, and the building of massive secret cities across the United States during World War II to create the most powerful weapon humanity

has ever seen.4 The story we were told about the bomb was about impossibility, glory, and terror, which the movie spectacularly recounted.

Yet, for all its focus on the characters in that story, the film fails to truly humanize them. If it displayed a beautiful sun-dappled forest in which the audience could imagine itself walking, then maybe viewers could feel a slight connection to Oppenheimer, and he would not seem like such an enigma. If the film depicted the native New Mexicans and Indigenous people who did housework in the homes of the scientists and performed janitorial services at the lab, then maybe filmgoers could relate more to the sacrifice that these Americans endured to make this weapon a reality.

Yet, for all its focus on the characters in that story, the film fails to truly humanize them. If it displayed a beautiful sun-dappled forest in which the audience could imagine itself walking, then maybe viewers could feel a slight connection to Oppenheimer, and he would not seem like such an enigma. If the film depicted the native New Mexicans and Indigenous people who did housework in the homes of the scientists and performed janitorial services at the lab, then maybe filmgoers could relate more to the sacrifice that these Americans endured to make this weapon a reality.

The bomb and humanity became lost in the plot about politics, ego, and deception. Viewers were left feeling angry at Lewis Strauss rather than at the decision to proceed with the Trinity Test despite the proximity to communities in the Tularosa Basin that were not warned about the risk and today still struggle with cancer and other health problems caused by proximity to the bomb blast.5 Viewers were left feeling sorry for Oppenheimer for being cast aside by the government he served and not for the victims of the bombings in Nagasaki and Hiroshima. By failing to capture the New Mexico that Oppenheimer loved or present realistic narratives about the women and native people who were integral to the project,6 the film contributes to the abstract and idealized notion of nuclear weapons.

The film concludes with a foreboding message as Oppenheimer laments to Albert Einstein about setting off a chain reaction that would destroy the entire universe. Yet, there was a sign of hope in the movie with the mention of the need for international control of fissile material and for monitoring the peaceful use of nuclear energy. The International Atomic Energy Agency probably did not expect the subtle shoutouts from this huge summer blockbuster. By bringing fresh attention to the dangers of nuclear weapons, the film has created a moment for action, including the need to strengthen the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act to assist New Mexico’s Downwinders population, which for too long has been excluded from the acknowledgment and benefits that other communities exposed to nuclear testing and uranium mining have received since 1990.7

ENDNOTES

1. Tewa Women United, “Oppenheimer - and the Other Side of the Story,” July 18, 2023, https://tewawomenunited.org/2023/07/oppenheimer-and-the-other-side-of-the-story.

2. Grace Jidoun, “Where Was Oppenheimer Filmed? Discover Christopher Nolan’s Authentic Shoot Locations,” NBC, July 28, 2023,

https://www.nbc.com/nbc-insider/oppenheimer-filming-locations.

3. Myrriah Gómez, Nuclear Nuevo México: Colonialism and the Effects of the Nuclear Industrial Complex on Nuevomexicanos (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2022).

4. Los Alamos National Laboratory, “The Town That Never Was,” 1980 (20-minute film), https://youtu.be/DGWmFTqXHoY?si=WqA7U4QuCeBeZbpR.

5. Karin Brulliard and Samuel Gilbert, “No ‘Oppenheimer’ Fanfare for Those Caught in First Atomic Bomb’s Fallout,” The Washington Post, July 29, 2023

6. Radhika Seth, “Justice for the Women of Oppenheimer,” Vogue, July 22, 2023.

7. Griffin Rushton, “Senate Approves New Mexico Downwinders’ Inclusion in RECA Amendment,” KOB 4, July 30, 2023, https://www.kob.com/new-mexico/senate-approves-new-mexico-downwinders-inclusion-in-reca-amendment/.