"In my home there are few publications that we actually get hard copies of, but [Arms Control Today] is one and it's the only one my husband and I fight over who gets to read it first."

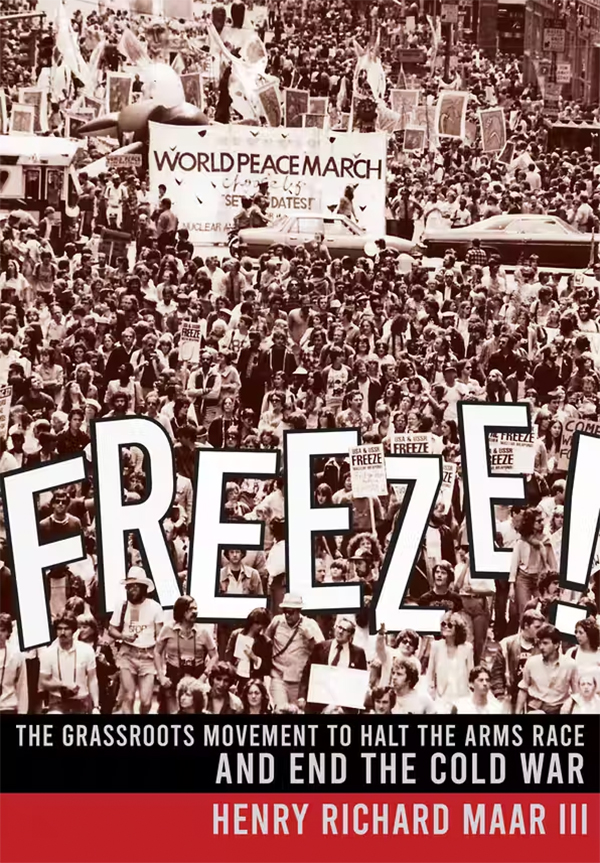

Freeze! The Grassroots Movement to Halt the Arms Race and End the Cold War

September 2022

Nuclear Anxieties, Then and Now

Freeze! The Grassroots Movement

Freeze! The Grassroots Movement

to Halt the Arms Race and End the

Cold War

Henry Richard Maar III

Cornell University Press, 2022

Reviewed by David Cortright

Nuclear dangers have increased with Russia’s deadly gambit of using nuclear threats to shield its military aggression in Ukraine. The war began with Russian President Vladimir Putin raising the alert status of Russian strategic forces “to a special regime of combat duty” and threatening states that might consider intervening to help Ukraine with consequences “such as you have never seen in your entire history.” Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov declared NATO arms shipments to Ukraine “a legitimate target” for attack, saying the risk of nuclear war is “serious,” “real,” and “cannot be underestimated.”1 In June, while Western leaders met in Germany, Putin pointedly announced the transfer of nuclear-capable missiles to Belarus.2

Some analysts argue that the risk of nuclear weapons use is greater now than during the Cuban missile crisis,3 but the present crisis can also be compared with the nuclear anxiety of the early 1980s. Reagan administration officials spoke of fighting and winning a nuclear war, and the arms race was in full throttle, with each side adding more threatening strategic weapons to arsenals already brimming with tens of thousands of warheads. Deployments of intermediate-range nuclear forces in Europe threatened to turn the continent into an atomic battleground.

Few people remember the extraordinary levels of existential fear that gripped the public in those years and drove millions of people to support the nuclear freeze movement in the United States and disarmament campaigns in Europe. According to a Gallup poll in September 1981, 70 percent of U.S. respondents felt that nuclear war was a real possibility, with 30 percent considering the chances of such a conflict to be “good” or “certain.”4

U.S. President Ronald Reagan and senior officials in his administration stoked these fears with hostile anti-Soviet rhetoric and a policy of rejecting arms control in favor of more weapons. They talked loosely of using nuclear weapons. Secretary of State Alexander Haig told members of Congress that, in the event of conventional war in Europe, the United States might fire a nuclear weapon “for demonstrative purposes.” Reagan discussed the possibility of a limited nuclear war in Europe, telling reporters, “I could see where you could have the exchange of tactical weapons against troops in the field without it bringing either one of the major powers to pushing the button.” The administration created a crisis relocation plan to prepare for possible nuclear attack, urging citizens to build bomb shelters and ordering cities to plan for mass evacuation.

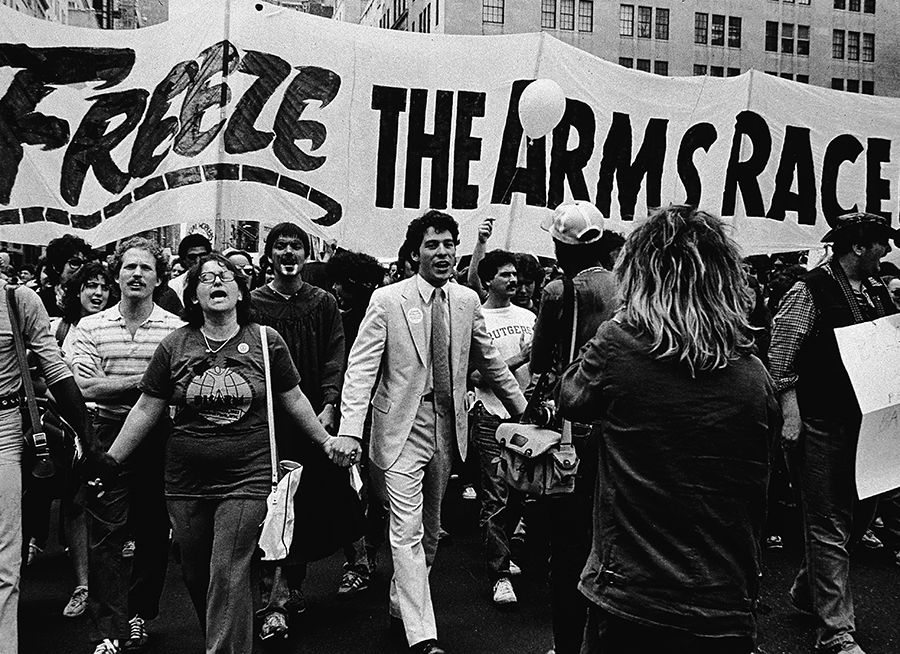

In the face of such insanity, people took to the streets in unprecedented numbers and organized politically to demand a halt to the arms race. Many rallied to the proposal developed by security analyst Randall Forsberg, then a doctoral student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for a mutual, verifiable freeze on the production, testing, and deployment of nuclear weapons by the United States and the Soviet Union. The resulting movement for a bilateral nuclear freeze sparked one of the largest waves of popular protest in U.S. history.

On June 12, 1982, an estimated one million people marched to New York’s Central Park for a rally to freeze and reverse the arms race. The proposition to freeze U.S. and Soviet weapons was on the ballot in 10 states and the District of Columbia and was approved in all except Arizona. The freeze proposition was affirmed by voters or lawmakers in 29 cities, 800 town meetings, and 17 state legislatures. Hundreds of national professional organizations endorsed the freeze, as did 25 of the nation’s largest trade unions. The freeze movement also was supported by many artists and performers and helped to shape popular culture, most dramatically in the broadcast of the 1983 television film on the effects of a nuclear attack, “The Day After,” watched by 100 million viewers.

The story of this historic transformation and the rise of the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign as an activist organization is told well in Freeze! The Grassroots Movement to Halt the Arms Race and End the Cold War. Written by historian Henry Richard Maar III, the book offers a compelling, well-documented analysis showing how the freeze movement fundamentally altered the terms of debate about nuclear weapons policy and had a significant impact on the rhetoric and policies of the Reagan administration. Maar confirms and expands on the analyses of a number of authors, myself included, who argue that citizen activism in the 1980s shifted political decision-making toward support for arms control and nuclear reductions.

The story of this historic transformation and the rise of the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign as an activist organization is told well in Freeze! The Grassroots Movement to Halt the Arms Race and End the Cold War. Written by historian Henry Richard Maar III, the book offers a compelling, well-documented analysis showing how the freeze movement fundamentally altered the terms of debate about nuclear weapons policy and had a significant impact on the rhetoric and policies of the Reagan administration. Maar confirms and expands on the analyses of a number of authors, myself included, who argue that citizen activism in the 1980s shifted political decision-making toward support for arms control and nuclear reductions.

Maar adds to scholarship on the freeze era by drawing from declassified archival records of senior Reagan administration officials, including internal staff memos by national security advisers William Clark and Bud McFarlane and White House Communications Director David Gergen. The author quotes the concerns of Clark and others about an “accelerating growth of anti-nuclear sentiment” and “the grassroots strength of the nuclear freeze issue.” The White House mounted a major effort to counter the freeze, Maar reveals, creating a “public affairs group on nuclear issues,” chaired by McFarlane, which sponsored widespread public communications efforts, especially in states where the freeze proposition was on the ballot.

Although the administration publicly criticized the freeze, internally it recognized the need to accommodate the movement. Reagan toned down his rhetoric and abandoned talk of fighting a nuclear war. The administration began to change its policies and announced its willingness to enter negotiations with the Soviets. The initial talks were fruitless, but members of Congress, under pressure from freeze constituents, demanded that the White House show progress on arms control and moderate the U.S. bargaining position. Gradually, the two sides showed greater flexibility, and the talks produced historic arms reduction agreements in the administration’s second term.

Maar deftly captures the essential characteristics of the freeze movement that contributed to its massive scale and political success: the mobilizing and communicative power of the freeze idea, the grassroots origins and nature of the campaign, and the moral legitimacy and respectability that came with support from the religious community. Maar also examines the contentious nuclear freeze debate in Congress and the role of freeze activists in the 1984 presidential election.

The freeze concept gave the disarmament movement a convincing narrative framework for mobilizing public support. Forsberg’s proposal for a bilateral freeze on U.S. and Soviet weapons enabled the movement to transcend the binary logic of the Cold War. The freeze could not be dismissed as unilateralist or pro-Soviet. It was, Maar writes, “at once both conservative and radical,” conservative in not demanding that either side cut its arsenal unilaterally but radical in demanding a halt to the entire system of nuclear weapons testing, production, and deployment.

The freeze concept was user friendly, easily understandable, and readily acceptable to the average citizen. It radically democratized the nuclear debate, transforming it from a highly technical field dominated by white men with advanced degrees into a subject in which every citizen had a stake and could have a voice. Polls at the time showed 70 percent or more of the public in favor of the bilateral nuclear freeze.

The authenticity and political clout of the freeze movement was based on grassroots mobilization. The organizing model was developed by Randy Kehler, an activist with the War Resisters League who had been imprisoned as a draft resister during the Vietnam War and at the time was working at the Traprock Peace Center in western Massachusetts. In 1980, Kehler and other local peace activists placed the freeze proposition on the ballot in three nearby state senate districts. The measure asked voters to instruct state officials to support a resolution urging the White House to propose a bilateral nuclear freeze to the Soviet Union. The measure also called for transferring funds from nuclear weapons development to civilian use. It was approved by 59 percent of voters in electoral districts that went for Reagan in the presidential vote. The results demonstrated the bipartisan appeal of the freeze and the value of a local referendum model.

The Massachusetts votes sparked a grassroots prairie fire of organizing across the country. Referendum campaigns began in California and other states, and nuclear freeze groups popped up in hundreds of cities and towns. In March 1981, activists gathered at Georgetown University for a conference to create the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign, a loosely structured coordinating body with limited staff, annual conferences, and a national committee of state and local organizers that provided strategic direction for the wider freeze movement.

The most significant constituency for disarmament in the 1980s was the religious community. The National Council of Churches and most major Protestant denominations, progressive evangelicals, and African-American church leaders endorsed the freeze and called for reversing the arms race, as did many Jewish and Muslim voices. This nearly universal call for peace from faith communities gave legitimacy and respectability to the disarmament movement.

The most influential body within the religious community was the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, now the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Maar describes the Catholic bishops as the “moral backbone” of the freeze movement and devotes considerable attention to their groundbreaking 1983 pastoral statement, “The Challenge of Peace: God’s Promise and Our Response,” which criticized elements of the administration’s nuclear buildup.

Although the bishops did not explicitly endorse the freeze proposition, the pastoral statement declared support for “immediate bilateral agreements to halt the testing, production and deployment of new nuclear weapon systems.” That language was identical to the freeze campaign’s founding declaration, as Maar notes.

The freeze campaign became entangled in a frustrating legislative process on Capitol Hill. Forsberg’s call to halt the arms race was not intended as a legislative initiative, least of all the vaguely worded nonbinding measure that came to a vote in Congress. The campaign’s original strategy called for several years of building grassroots political clout in states and congressional districts before proposing freeze legislation or engaging political candidates. When members of the U.S. House and Senate introduced freeze resolutions, however, the campaign had little choice but to go along, although with growing skepticism as the language of the resolution became muddled and contradictory through the addition of qualifying amendments. The House approved the measure in May 1983, but the legislation had no substantive impact on restraining the nuclear buildup.

The freeze campaign also faced challenges when Democratic Party candidates tried to ride the coattails of the popular movement during the 1984 election. All major Democratic Party candidates endorsed the freeze, including presidential nominee Senator Walter Mondale (Minn.). When Reagan trounced Mondale in the election, some interpreted this as a defeat for the freeze movement. Maar adopts this framing and claims that Reagan’s victory caused “irreparable damage” to the freeze campaign, which “lost in 1984” and was left “smoldering in the ashes” of Mondale’s defeat. Such claims about the “waning” of the movement at that time are overstated, but Maar is right to show the difficulty of sustaining grassroots pressure when politicians try to undercut or capture a movement’s popular support.

Reagan won the election in part by coopting the freeze message and portraying himself as a peace candidate. In his 1984 State of the Union address, Reagan famously declared “a nuclear war cannot be won, and must never be fought.” In his address to the United Nations that September, he adopted a tone of moderation and called for the superpowers to “approach each other” for the sake of world peace. As Kehler observed, “[T]he Ronald Reagan elected in 1984 was quite different from the Ronald Reagan of 1980, a leader promising moderation and arms negotiations with the Soviets.” The freeze movement created the political climate for arms reduction, and Reagan adjusted his sails accordingly.

Although the freeze campaign lost some momentum after 1984, the movement as a whole remained vibrant. Membership levels at the Committee for a SANE Nuclear Policy and other groups continued to rise, and legislative lobbying efforts achieved some successes. The Campaign to Stop the MX, which ran parallel to the freeze campaign, helped to force the cancellation of the missile’s mobile basing system in Utah and Nevada and cut the number of missiles from 200 to 50 over the course of an epic five-year lobbying campaign.

The freeze campaign and allied groups achieved legislative success implementing the concept of a “quick freeze.” Emerging from the 1985 national freeze conference, the idea was for Congress to use its power of the purse to halt funding for nuclear weapons development. The strategy was applied successfully, after a multiyear legislative effort, when the House and Senate passed legislation to cut off funds for nuclear weapons testing. This occurred as Reagan and President George H.W. Bush negotiated with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev for the strategic arms reduction treaties that ended the Cold War.

Are there lessons from the freeze movement for today? The salience of nuclear issues has been low in recent decades, but that may change as the consequences of Putin’s nuclear saber rattling become clearer. The nuclear taboo is weaker now, and the risk of weapons use has increased.5 Whatever happens with the war, Russia’s sinister use of nuclear threats to intimidate Ukraine and NATO requires a reckoning with the role of nuclear arms in global affairs and adds urgency to the goal of eliminating these weapons.6

How best can one move toward that essential objective? The freeze movement shows that large-scale citizen mobilization can help to reduce nuclear dangers.7 Maar’s important examination of the freeze campaign highlights the challenges of that effort but also the ingredients that brought success to the movement: a clear mobilizing narrative, the development of creative grassroots strategies, and an appeal to moral values in partnership with the religious community.

ENDNOTES

1. David Meyer, “Russia Now Warns of 'Considerable' Nuclear War Risk, but Ukraine Says It's Just Trying to Scare the World Off Arming Kyiv,” Fortune, April 26, 2022.

2. “Russia to Send Belarus Nuclear-Capable Missiles Within Months, as G7 Leaders Gather in Germany,” The Guardian, June 25, 2022.

3. Lawrence Korb and Stephen Cimbala, “Why the War in Ukraine Poses a Greater Nuclear Risk Than the Cuban Missile Crisis,” Just Security, April 12, 2022.

4. “Poll Finds 7 Out of 10 Imagining Outbreak of Soviet Nuclear War,” The Washington Post, September 27, 1981, p. 17.

5. Nina Tannenwald, “Is Using Nuclear Weapons Still Taboo?” Foreign Policy, July 1, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/01/nuclear-war-taboo-arms-control-russia-ukraine-deterrence/.

6. Daryl G. Kimball, “How to Avoid Nuclear Catastrophe—and a Costly New Arms Race,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March 11, 2022.

7. Steve Ladd, email communication with author, June 5, 2022.

David Cortright is a professor emeritus in the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame.

Correction: In "Freeze! The Grassroots Movement to Halt the Arms Race and End the Cold War," the impact of The Campaign to Stop the MX was reported incorrectly. The campaign helped to cut the number of missiles from 200 to 50, not 40, as initially reported."