The violence in Ukraine and rising tension in the Baltics, combined with concern about Russian nuclear doctrine and posturing, has heightened the risk of nuclear conflict in Europe. As William Perry, former Secretary of Defense under President Bill Clinton, recently warned, “A new danger has been rising in the past three years and that is the possibility there might be a nuclear exchange between the United States and Russia.”

A recent uptick in fighting in Ukraine, last week’s unrest in Belarus and Russia, and increasing concern in Washington and Brussels about the solidity of the NATO Article V commitment that an attack against one member is an attack against all have brought greater urgency to preventing catastrophe.

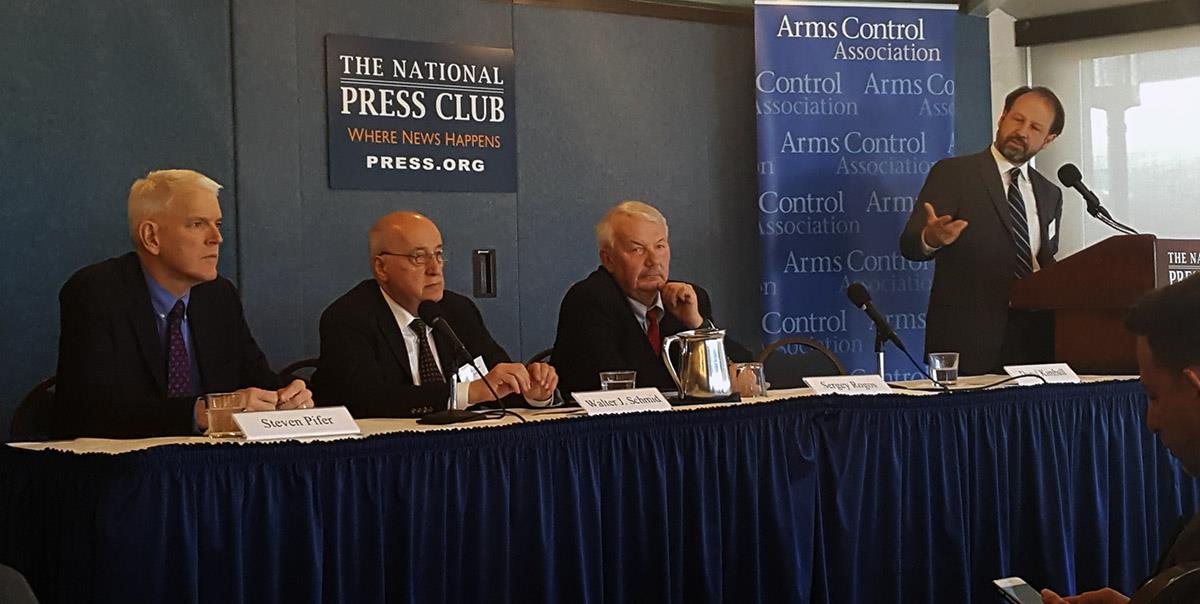

Experts at last week’s Carnegie International Nuclear Policy Conference and meeting of the Deep Cuts Commission discussed a range of solutions, including conflict resolution, addressing conventional force imbalances, conventional force restraint and confidence building measures, and renewed dialogue between the United States and Russia on nuclear issues.

Experts at last week’s Carnegie International Nuclear Policy Conference and meeting of the Deep Cuts Commission discussed a range of solutions, including conflict resolution, addressing conventional force imbalances, conventional force restraint and confidence building measures, and renewed dialogue between the United States and Russia on nuclear issues.

The highest probability for direct conflict between the United States and Russia is in Eastern Europe, given the potential for ongoing violence in Ukraine to spread to neighboring countries such as Poland and the Baltics, or for Russia to target NATO forces in this common border area. Unlike Ukraine, Poland and the Baltic nations are NATO members. If Russian aggression were to threaten them, NATO would be obligated to intervene. Such intervention could trigger a regional conventional conflict.

Strained U.S.-Russian relations have increased the possibility of a conventional conflict in Eastern Europe. Speaking at the Carnegie conference, Kadri Liik, senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, described the Baltic nations as a “soft underbelly” where Russia might seek to target the United States and NATO if tensions were to intensify elsewhere, such as Syria or Ukraine. She added that the election of Donald Trump could “make Russia more aggressive in the Baltics.” President Donald Trump’s statements questioning the legitimacy of NATO could remove Moscow’s fear that Russian interference in the Baltics could provoke a U.S.-backed NATO response.

Recent actions by Moscow have demonstrated ambitions to destabilize the West, perhaps with an end-goal of redesigning the global order to secure an elevated position for Russia. Given the lengths Russia has gone to violate the European security order by annexing Crimea, support a separatist movement in Ukraine, and interfere in the American election, a Russian military move against the Baltics, while unlikely, cannot be ruled out.

Even more disturbing is the potential that a conventional face-off between Russia and NATO in Eastern Europe could escalate to the nuclear level.

According to U.S. and NATO officials, Russian military doctrine envisions the possible employment of a small number of lower-yield nuclear weapons to stave off defeat in the event of a conventional conflict with NATO. This concept is frequently referred to as the Russian ‘escalate to de-escalate’ doctrine. Although other experts disagree about whether this concept is truly part of Russian military planning, Kremlin rhetoric demonstrates that it is part of the Russian defense mindset.

Alexey Arbatov, head of the Center for International Security at the Institute of Primakov National Research Institute of World Economy and International Relations, said at the Carnegie Conference that the United States and Russia hold incompatible views on both the role of NATO and the conventional force balance in Eastern Europe. While the United States points to Russian conventional superiority over its weaker neighbors, Moscow views Russia’s conventional capability as vastly inferior to that of NATO and the United States.

According to Arbatov, Moscow perceives even “modest deployments” in NATO countries as a “forward echelon of superior NATO forces deployed across Europe and across the Atlantic, that could be quickly redeployed to Russian borders.

A much higher premium thus needs to be placed by both NATO and Russia on reducing the risk of conflict before it escalates to the nuclear level.

Prevention requires full implementation of the Minsk II peace process in Ukraine, a system in the Baltics that allows NATO and Russia to better monitor each other's forces, negotiations to reduce force instabilities, and the application of arms control and transparency measures to low-yield nuclear weapons.

In a 2016 report, the Deep Cuts Commission, a 21-member group of nuclear experts from the United States, Russia, and Germany committed to arms control and nuclear nonproliferation, laid out recommendations to bring the United States and Russia back from the brink. The Commission suggests implementing Joint Military Incident Prevention and Communications Cell linked to a European Risk Reduction center to reduce the risk of military incidents, initiating a NATO-Russia dialogue to safeguard the interests of the Baltic states, and renewed talks on a range of nuclear issues, including extending New START and resolving respective concerns respective concerns about compliance with the 1987 Intermediate Range Force Treaty.

With regard to preventing use of low-yield weapons, it is critical for the United States to pursue dialogue on ways to avoid destabilizing conventional force imbalances, especially in the common border area between NATO and Russia. This dialogue could fuel discussion on regulating tactical nuclear weapons, which in the past have not been part of the bilateral Washington-Moscow arms control process. If Russia is more confident in the stability of the balance of conventional power, such confidence could reduce its potential incentive to use tactical nuclear weapons to “escalate to de-escalate.”

Implementing Minsk II is an ongoing challenge, but the United States should consider increasing its engagement with European allies to both apply pressure on Russia to honor the agreement and support the Ukrainian reform agenda. Increasing transparency and communication along the NATO-Russia border is a critical step to lower the risk of conflict, given the proximity of NATO member state and the Russian militaries.

The poor state of U.S.-Russian relations has significantly compromised progress in nuclear arms control and nonproliferation and increased the risk of conventional and even nuclear conflict in Europe. Doubling down on efforts to resolve the Ukraine conflict, reduce security concerns in the Baltic area, and increase communication regarding vital arms treaties and military practice could reduce that risk.