Inheriting the Bomb: The Collapse of the USSR and the Nuclear Disarmament of Ukraine

April 2023

Ukrainian Nuclear Disarmament: Blunder or Base Camp?

Inheriting the Bomb: The Collapse of the USSR and the Nuclear Disarmament of Ukraine

Inheriting the Bomb: The Collapse of the USSR and the Nuclear Disarmament of Ukraine

By Mariana Budjeryn

Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022

Reviewed by Douglas B. Shaw

Mariana Budjeryn’s Inheriting the Bomb: The Collapse of the USSR and the Nuclear Disarmament of Ukraine adds depth to our understanding of how Ukraine’s nuclear decisions after the collapse of the Soviet Union relate to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s 2022 invasion and how nuclear disarmament and the state relate to the world order. It provides a rich description of an important historical example of nuclear disarmament and calls attention to specific tensions between nuclear weapons and state security.

The book offers important lessons, including that nuclear decisions are multicausal, domestic political contexts matter, U.S. fears of proliferation could be a self-fulfilling prophecy, the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty matters, and the seemingly powerless can be powerful.

It also combines authentic scholarship with a poetic comprehension that challenges the common understanding of successful nuclear disarmament in Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan as a single U.S. nonproliferation victory facilitated by the Soviet defeat in the Cold War. Challenging this oversimplification is important to help understand why, if we “won” and they “lost,” so many Ukrainians have perished in today’s Russian war and why Russian nuclear weapons still threaten the United States with mass destruction.

Fifteen years ago, in outlining the need for a “vision and steps” approach to nuclear disarmament, former U.S. Senator Sam Nunn (D-Ga.) likened nuclear disarmament to reaching a high “mountaintop.” That goal is difficult to visualize today, but it is useful for measuring progress and establishing a higher, safer “base camp” as an interim step. Amid Ukraine’s stunning self-defense against Russian invaders, Budjeryn paints an intricate picture of Ukrainian nuclear disarmament that if it survives, could help the world visualize such a base camp.

Former Nuclear Statehood

Budjeryn identifies two reasons, unrelated to Western pressure, why nuclear disarmament was written into Ukraine’s Declaration of Sovereignty: Chernobyl and independence. She centers the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster as a sharp demonstration of “Ukraine’s lack of political agency in its own affairs” and as a motivation for the emergence of Ukraine as an independent state. As the author recounts, “Chernobyl became a banner under which all Ukrainians could be rallied toward a greater independence from Moscow, on humanitarian and civic, rather than ethnonationalistic, grounds.”

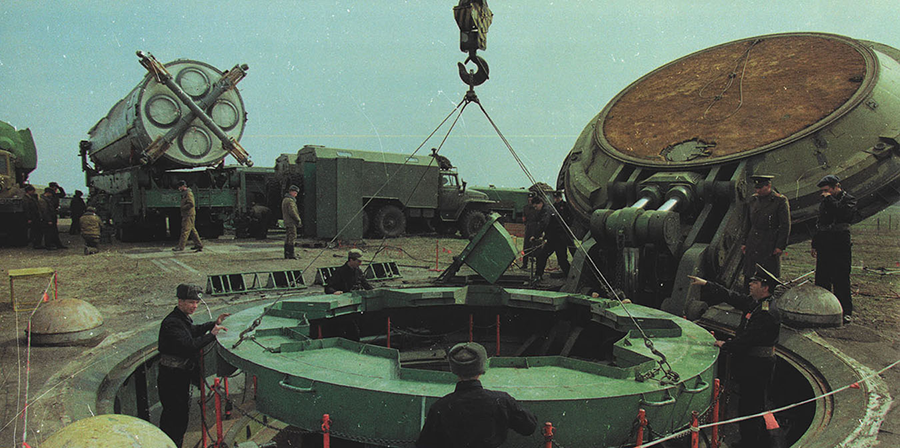

Ukraine’s nuclear disarmament was neither utopian naïveté nor enlightenment, but rather an imperative of independence. Moscow exercised direct control over nuclear weapons throughout the Soviet Union by means of rigidly centralized weapons command structures that were an obstacle to local self-determination. From the perspective of Ukrainians under Soviet rule, “[T]here were nuclear weapons in Ukraine and at the same time it was as if there were none” because these weapons were managed entirely by Moscow. The Soviet Union’s “armed forces, its enormous nuclear arsenal, and its military-industrial complex now stood, largely intact, resembling an exoskeleton from which the political body had suddenly slipped out,” Budjeryn recalls. Moscow continued to exploit local unfamiliarity with the nuclear weapons operations to avoid sharing control of the nuclear weapons in Ukraine. As Russian President Boris Yeltsin explained, “[T]hey don’t know how things work.” Even the reconstruction of the Commonwealth of Independent States strategic forces excluded the republics from nuclear decision-making.

Ukraine’s nuclear disarmament was neither utopian naïveté nor enlightenment, but rather an imperative of independence. Moscow exercised direct control over nuclear weapons throughout the Soviet Union by means of rigidly centralized weapons command structures that were an obstacle to local self-determination. From the perspective of Ukrainians under Soviet rule, “[T]here were nuclear weapons in Ukraine and at the same time it was as if there were none” because these weapons were managed entirely by Moscow. The Soviet Union’s “armed forces, its enormous nuclear arsenal, and its military-industrial complex now stood, largely intact, resembling an exoskeleton from which the political body had suddenly slipped out,” Budjeryn recalls. Moscow continued to exploit local unfamiliarity with the nuclear weapons operations to avoid sharing control of the nuclear weapons in Ukraine. As Russian President Boris Yeltsin explained, “[T]hey don’t know how things work.” Even the reconstruction of the Commonwealth of Independent States strategic forces excluded the republics from nuclear decision-making.

Deterrence is not local politics, but nuclear arsenals and nuclear disarmament are. Some 30,000 troops of the Soviet 43rd Strategic Missile Army and massive defense enterprises, including intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) manufacturer Pivdenmash, were among the many who could be displaced by nuclear disarmament. Unsurprisingly, “Ukrainian political elites diverged with regards to what exactly nuclear ownership entailed.” The Ukrainian president and Defense Ministry made claims to nuclear weapons ownership in an effort to obtain financial compensation and security guarantees from foreign governments. Some members of the Rada, Ukraine’s legislature, sought to extract more value from abroad by using nuclear ownership as a political hedge. Some members of the Ukrainian defense establishment sought to soften the dislocation by converting Ukraine’s massive inheritance of ICBMs, targeted at the United States and tipped with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), into a conventional deterrent.

The Ukrainian military-industrial complex played a major but sometimes confusing role in shaping Ukrainian nuclear disarmament. The ICBMs with MIRVs, produced by Ukraine’s Pivdenmash and left stationed in Ukraine after the Soviet Union collapsed, were ill-suited to Ukrainian defense needs. Their nuclear warheads required ongoing maintenance from enterprises in Russia and were not appropriate to hold targets in Russia at risk. Leftover Soviet air-launched cruise missiles (ALCMs) would have been a better fit for Ukraine’s prospective deterrence needs, but Budjeryn observes that “the ALCMs, it seems, did not have a lobby.” When former Pivdenmash director Leonid Kuchma became Ukraine’s second president in 1994, his advocacy for converting Ukraine’s ICBMs to carry conventional payloads was reported in The Economist under the headline “Ukraine: A Nuclear State.”

Ultimately, although cobbling together a nuclear deterrent force would have been technically possible, Ukrainian political leaders judged it unwise. As Budjeryn writes, Ukraine “needed to join the international community more than it could afford to defy it.” There was an upside, however, as “Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine found themselves in a position of leverage vis-à-vis powerful nuclear-armed states if only by virtue of their sovereignty and international law.”

Beyond Strawman Nuclear Disarmament

Budjeryn’s characterization of “Ukraine’s nuclear disarmament” is provocative. The elimination of nuclear weapons from all former Soviet republics other than Russia is often treated as a single, unremarkable success of U.S. nonproliferation policy, a historical footnote from which broader solutions should not be sought. The author contradicts this common view with a meticulous, factual demonstration that Ukraine’s nuclear disarmament was an uncertain but relentlessly pursued path of positive actions reflecting national interest and involving great risk, expense, and effort. This perspective contrasts starkly with the more popular strawman version of nuclear disarmament as a sort of utopian mirage, desirable but wholly unattainable.

Budjeryn pursues her concept of nuclear disarmament unapologetically, asserting that “the story of Ukraine, as well as Belarus and Kazakhstan, is a testament that nuclear disarmament is possible.” This achievable nuclear disarmament is a global human challenge but perhaps one most easily grasped from a Ukrainian perspective: “I knew that no thing created by humans is fail-safe and that we could not afford a nuclear failure.”

The author’s concept of nuclear disarmament complicates the common understanding of the state. Prevailing realist conceptions of world order privilege states as unitary, rational actors that are alike in kind, analogous in their interactions to billiard balls bouncing around a pool table. By contrast, Budjeryn describes the distinct character of an independent Ukrainian state in opposition to the bungling nuclear authoritarianism of the Moscow-based Soviet center, in which “not even the Politburo members had the full picture.”

She locates newly independent Ukraine in a world in which states are increasingly constructed by international law, writing that as these new independent states emerged, “the nuclear nonproliferation regime made up of institutions and shared understandings of the meaning of nuclear weapons and their role in international politics, was a constitutive part of [world] order.” This view of the state as a creature of international law may have been more familiar in Ukraine, which was a member of the United Nations and party to some 120 international treaties while part of the Soviet Union. Even if “the state made war and war made the state,” as Charles Tilly famously observed, law is the material from which contemporary states are fashioned.

At the same time, Budjeryn sees that, in the collapse of the bipolar Cold War world order, “nuclear weapons gained new meanings.” The world’s largest nuclear arsenal had not preserved Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s control during the 1991 coup, when “minutes before [he] had the power to authorize the launch of hundreds of intercontinental missiles [and suddenly] was rendered impotent.” Ukraine’s first president, Leonid Kravchuk, described nuclear weapons as a liability that “can be more dangerous than Chernobyl.” Worse still, she writes, nuclear weapons made Ukraine “automatically…the object of nuclear deterrence for the United States, Russia, and other nuclear states.” From this perspective, nuclear weapons became more unpredictable, existential dangers than reliable tools of policy. Ukraine responded creatively by attempting “to fashion its nuclear inheritance as property, not weapons per se.”

What Someone Will Pay

Depictions of Russia as “Upper Volta with rockets” and fears that the Soviet Union’s disintegration would yield “Yugoslavia with nukes” focused U.S. imaginations on proximate goals of securing and consolidating the world’s largest nuclear arsenal. The United States prioritized preventing the emergence of nuclear-armed states other than Russia. “On the one hand, this priority reflected the extraordinary positive insights of Senators Sam Nunn and Richard Lugar, and others, that a new kind of Cooperative Threat Reduction was necessary…. What followed was a ‘very curious form of cooperation’ in which the United States ‘rooted for the safe transit of nuclear weapons from these other countries back to Russia so they could then be put online and aimed at the United States.’”

Washington’s bold intervention, however, remained cautious with regard to regional politics. Budjeryn recalls that “Washington preferred to ‘deal with the devil we know’ in Moscow, and was slow to develop relationships in the new independent states.” When Jack Matlock, U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, advised that the United States should open diplomatic posts in Soviet cities outside Moscow, President George H.W. Bush asked, “[F]or what?” Ukraine soon realized that nuclear weapons were the only leverage it had to bolster its security.

Washington’s bold intervention, however, remained cautious with regard to regional politics. Budjeryn recalls that “Washington preferred to ‘deal with the devil we know’ in Moscow, and was slow to develop relationships in the new independent states.” When Jack Matlock, U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, advised that the United States should open diplomatic posts in Soviet cities outside Moscow, President George H.W. Bush asked, “[F]or what?” Ukraine soon realized that nuclear weapons were the only leverage it had to bolster its security.

U.S. myopia toward Ukrainian interests slowed nuclear disarmament progress. As Kravchuk expressed in dismay, “[P]ressure always provokes counter-pressure.” From the Ukrainian perspective, the state’s experience “as an integral part of a nuclear superpower [that] inherited nuclear arms after that power collapsed” was perfectly compatible with international law and had nothing in common with the nuclear proliferation intentions of what were then termed “pariah” or “rogue” states. Ukraine’s “claim to ‘nuclear ownership’ was a simple acknowledgement of this predicament.”

“In this atmosphere,” Budjeryn writes, “the opposition to nuclear disarmament grew, especially in the Rada, which in turn further exacerbated tensions with the United States and Russia.” Ukrainian Deputy Foreign Minister Borys Tarasyuk was quoted as observing that, “[i]f American policy had been different, Ukraine would have ratified START [the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty] long ago.”

After independence, Ukraine played a key role in constraining Russian nuclear options because, without Ukraine’s Pivdenmash, Russia could not sustain its MIRV ICBM force and, as a result, “it was either unilateral disarmament or conceding to bilateral de-MIRVing with the Americans.” Ukraine drove Russia into arms control concessions it would not otherwise have made.

Ukraine as a Nuclear Disarmament Base Camp

Budjeryn slams a factual wrecking ball through John Mearsheimer’s 1993 article “The Case for a Ukrainian Nuclear Deterrent.” Rather than a billiard ball struck by irresistible force, in the author’s telling, Ukraine had the agency and options to choose nuclear disarmament as a security strategy. She finds fault with Russia’s invasion not in Ukraine’s lack of arms but in the shoddy architecture of international law into which Ukraine’s independent sovereignty was inscribed. The 1994 Budapest Memorandum could have been a durable part of post-Cold War European security architecture, but instead ended up papering over a Ukraine-sized vacuum between the expanded NATO and revisionist Russia, she wrote. “That the next European war should be ignited in this vacuum is no surprise.” International law operates through anarchy when it accurately reflects the distribution of material power among states; it cannot constrain power disparities it does not acknowledge.

Budjeryn concludes with a clear-eyed understanding of the challenges and opportunities of negotiated security, writing that “a deal that can be achieved at low cost to the powerful parties, gives them a prerogative not only in making it, but also in breaking it.” As the author laments, the corollary with the present is that “[i]f Mr. Putin decides to launch a nuclear strike in Ukraine, there is nothing to deter him.” No threat of retaliation-in-kind is being leveled against Russia, none would be credible, and a rash retaliatory nuclear strike would risk escalation without resolving the conflict. Trying to stretch the U.S. extended deterrence to cover Ukraine through overreliance on strategic ambiguity risks escalation, undermines other U.S. deterrent threats, invites a commitment trap in which maintaining credibility could become an argument for a nuclear strike, and pushes nuclear deterrence further outside its antiquated design parameters.

Budjeryn’s larger point is more promising, that Ukraine demonstrates that nuclear disarmament is possible. “When all was said and done, the world’s third-largest nuclear arsenal was transformed into nuclear power-plant fuel, a heap of scrap metal, and four signatures under the Budapest Memorandum,” she writes.

Russia’s war will end someday. If Russia wins, it will be because of nuclear weapons, whether these weapons are used or not. If Ukraine wins, it will be despite nuclear weapons and will be proof that human beings have agency even in the toughest neighborhood. Nothing will balance the lives destroyed and displaced by Russian aggression or substitute for the world’s failure to prevent Putin’s war. Regardless, in addition to its moral necessity, Ukraine’s survival will demonstrate that nuclear disarmament is possible.