"[Arms Control Today] has become indispensable! I think it is the combination of the critical period we are in and the quality of the product. I found myself reading the May issue from cover to cover."

The Three-Competitor Future: U.S. Arms Control With Russia and China

March 2023

By Lynn Rusten and Mark Melamed

China’s expanding nuclear arsenal, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the looming expiration in 2026 of the last remaining U.S.-Russian strategic arms control agreement pose unprecedented challenges for U.S. nuclear policy and arms control. This evolving security landscape demands a fresh look at policies aimed at avoiding nuclear war and ensuring the security of the United States and its allies and partners.

Critically, Washington should seek to avert an unconstrained multilateral nuclear arms race that would be even more complicated and dangerous than the one during the Cold War. For the next decade, the United States should prioritize maintaining verifiable mutual limits with Russia on nuclear forces while deepening dialogue with China and aiming to bring it into bilateral and multilateral nuclear arms control over the longer term. To prevent limitless arms races and avert nuclear catastrophe, it will be necessary to establish a measure of strategic stability globally and regionally among these three nuclear powers.

Critically, Washington should seek to avert an unconstrained multilateral nuclear arms race that would be even more complicated and dangerous than the one during the Cold War. For the next decade, the United States should prioritize maintaining verifiable mutual limits with Russia on nuclear forces while deepening dialogue with China and aiming to bring it into bilateral and multilateral nuclear arms control over the longer term. To prevent limitless arms races and avert nuclear catastrophe, it will be necessary to establish a measure of strategic stability globally and regionally among these three nuclear powers.

For decades, the nuclear age was characterized by a bipolar system in which the two major powers—the former Soviet Union/Russia and the United States—possessed the lion’s share of the world’s nuclear weapons. At the high point of the Cold War, they had more than 30,000 nuclear warheads each. Today, the United States has approximately 3,708 nuclear warheads, and Russia is estimated to have 4,477 nuclear warheads. China, France, and the United Kingdom, as the other recognized nuclear powers, have roughly 400, 290, and 225 warheads, respectively.1

The United States has sized and postured its nuclear forces based on what it deemed necessary to deter Russia from an attack on the United States or its allies or to defeat Russia if deterrence failed. All other nuclear-armed adversaries and strategic threats that might be subject to U.S. nuclear deterrence policy, including China, were considered “lesser included cases,” meaning that whatever nuclear forces were sufficient for deterring Russia also would be sufficient to meet all other U.S. nuclear deterrence requirements. Given recent assessments of China’s plans to expand its nuclear forces over the next decade, that long-standing presumption is facing increasing scrutiny.

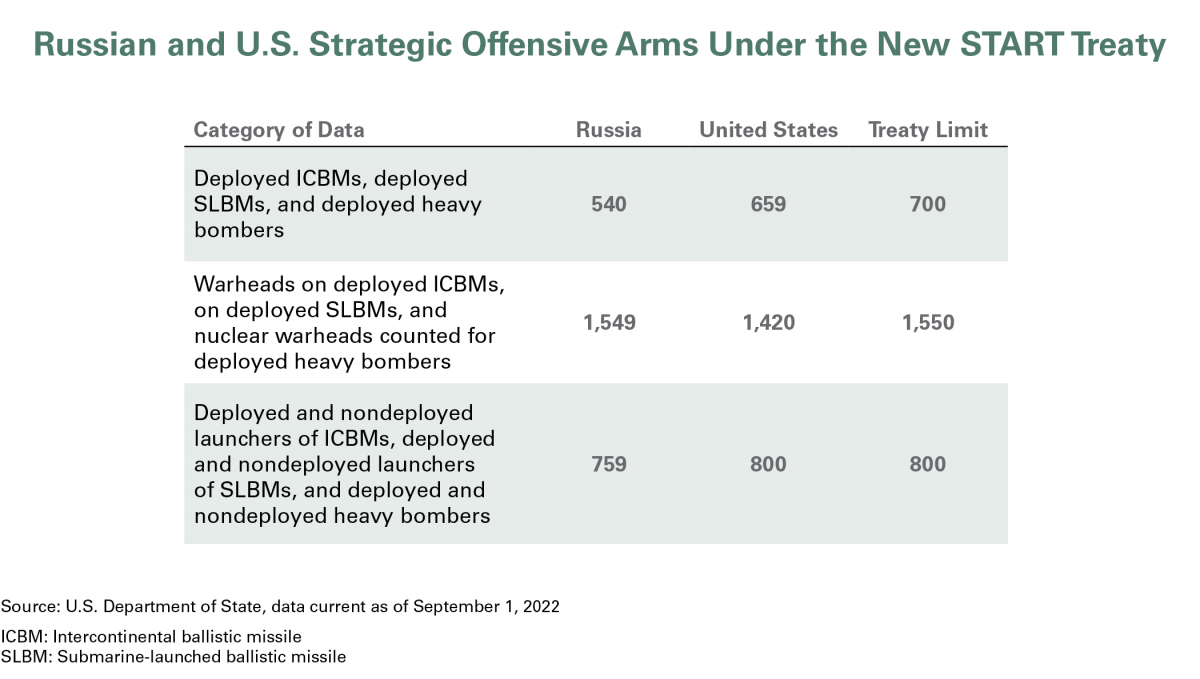

Since the early 1970s, the Soviet Union/Russia and the United States have negotiated a series of legally binding, verifiable agreements to limit and reduce their strategic nuclear arsenals. Today, the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) limits each side to 1,550 warheads on deployed strategic delivery vehicles. The United States must decide soon whether, when, and what to negotiate with Russia to replace New START before it expires in February 2026. Discussions with Russia on this goal began in the Trump administration and continued under the Biden administration in fall 2021, but broke down when Russia launched its illegal, unjustified war against Ukraine in late February 2022.

Moscow and Washington have since reaffirmed interest in a successor to New START, although each side’s conditions for resuming dialogue remain vague and have changed over time. In January 2023, the United States accused Russia of violating New START by failing to resume on-site inspections following an agreed two-year pause due to the COVID-19 pandemic and by failing to meet in the Bilateral Consultative Commission, the treaty’s implementing body.2 On February 21, President Vladimir Putin announced that Russia was suspending participation in the treaty by refraining from inspections but would continue to abide by it’s central limits.3 This marks the first time that treaty implementation has been disrupted by political tensions, and it raises the alarming and likely prospect that tensions will continue to impede the resumption of New START inspections and negotiations on a successor agreement.

Moscow and Washington have since reaffirmed interest in a successor to New START, although each side’s conditions for resuming dialogue remain vague and have changed over time. In January 2023, the United States accused Russia of violating New START by failing to resume on-site inspections following an agreed two-year pause due to the COVID-19 pandemic and by failing to meet in the Bilateral Consultative Commission, the treaty’s implementing body.2 On February 21, President Vladimir Putin announced that Russia was suspending participation in the treaty by refraining from inspections but would continue to abide by it’s central limits.3 This marks the first time that treaty implementation has been disrupted by political tensions, and it raises the alarming and likely prospect that tensions will continue to impede the resumption of New START inspections and negotiations on a successor agreement.

Enter China

Even as it contends with Russia, the United States is facing the unprecedented prospect of China as a near-peer nuclear competitor in the next 10 to 15 years. The 2022 U.S. Nuclear Posture Review cites China as “the overall pacing challenge for U.S. defense planning and a growing factor in evaluating our nuclear deterrent.”4 According to a 2022 U.S. Department of Defense report,5 China has more than 400 operational warheads, which is double the estimate in 2020, and if the expansion continues apace, will likely field about 1,500 warheads by 2035. The country is increasing the number of delivery platforms based on land, sea, and air, as well as the capacity to produce weapons-grade nuclear material.

This significant expansion of China’s nuclear force was not anticipated. China has long had a no-first-use policy regarding nuclear weapons. Its stockpile was intended to assure a second-strike capability for deterrent purposes and was not kept at a high state of readiness. China has not explained its nuclear plans publicly and has rebuffed U.S. proposals for dialogue about each side’s nuclear policy, forces, and posture.6

The Chinese expansion raises significant questions about how U.S. nuclear policy, deterrence, and arms control will operate in a world where China and Russia are likely to be nuclear peers of the United States.

Some U.S. experts have suggested that the 1,550 deployed strategic nuclear warheads permitted under New START will not be adequate to deter both Russia and China in the future, although they are not specific as to when that time will come or their assumptions about what size and posture of Russian and Chinese nuclear forces would trigger the need for increasing deployed U.S. strategic nuclear forces.7 These experts also have not indicated whether there is some finite number of U.S. nuclear weapons that would be adequate for deterrence if Russia and China each seek to match U.S. nuclear force levels. This raises the question of how the United States avoids an endless arms race if Russia and possibly China each seek to maintain parity with the United States.

Nuclear deterrence is not a simple mathematical problem. It is premised on convincing an adversary that any use of nuclear weapons will result in a devastating response. Russia and the United States have maintained rough parity in their nuclear forces and, through arms control agreements, have done so at increasingly lower levels. Yet, in a world with two near-peer nuclear competitors, it will not be possible for the United States to achieve parity with both Russia and China. Any effort to increase U.S. nuclear forces to match their combined total weapons likely will be countered by Russia’s determination to maintain parity with the United States and could stimulate China to further increase its nuclear forces. This is a recipe for an unending arms race and it will not stop with Washington, Moscow, and Beijing. If they expand, India, Pakistan, and potentially other nuclear-armed countries likely will conclude they need larger stockpiles as well.

Such an arms race is fundamentally unnecessary and counterproductive for advancing global and regional security and strategic stability. Deterrence is based on the credible threat of retaliation in response to an attack. It is implausible that Russia or China will conclude that they could sufficiently degrade U.S. nuclear capabilities with a first strike, even in a worst-case scenario of a joint Chinese-Russian first strike, to avoid massive retaliation.

There is no evidence to suggest that Russia and China are not adequately deterred by the existing U.S. nuclear stockpile or that the New START level of 1,550 deployed strategic nuclear warheads would not continue to deter them at least through 2035. This assumes that Russia remains at rough strategic parity with the United States and that China’s expansion does not exceed the current Pentagon estimate. Furthermore, there is no evidence that Russia and China would be more deterred by an increase in U.S. nuclear weapons. Instead, they may perceive such an expansion as evidence of plans for nuclear war-fighting, not deterrence.

Next Steps With Russia and China

Instead of resigning itself to or embracing an accelerated three-party arms race, the United States should recommit to efforts to mutually constrain the nuclear arsenals of its competitors and to strengthen strategic stability in an increasingly complex security environment. This effort will require elements of continuity and new approaches.

China has resisted proposals to join U.S.-Russian arms control negotiations. Nevertheless, the complexities of an emerging nuclear order in which China, Russia, and the United States will become near peers demand continued efforts to expand multilateral efforts to manage nuclear risks. In recent years, China has been more open to engagement through the P5 process, involving the five nuclear-weapon states recognized under the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). The United States should explore opportunities for broader and deeper engagement in that channel.

China’s embrace of a January 2022 statement, issued with France, Russia, the UK, and the United States and asserting that a “nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,” should be welcomed as an opening for deeper engagement. The nuclear-weapon states should build on the statement, which also said, “We each intend to maintain and further strengthen our national measures to prevent unauthorized or unintended use of nuclear weapons,” by considering a regular exchange of information on what each country is doing to strengthen such national measures. This could include commitments to undertake internal nuclear failsafe reviews, as the United States is now doing. Such reviews, which would be carried out independently by each nuclear-weapon state, would identify measures to strengthen safeguards against the unauthorized, inadvertent, or mistaken use of a nuclear weapon, including through false warning of an attack.

The United States also should explore the possibility of a modest trilateral Chinese-Russian-U.S. dialogue on nuclear risk reduction. Notwithstanding statements from Beijing and Moscow about the strength of their partnership and cooperation, Chinese concern about possible Russian use of nuclear weapons in Ukraine is evident. One sign came in November 2022 after Russian President Vladimir Putin made a thinly veiled nuclear threat and Chinese President Xi Jinping issued a public admonition that the international community should “jointly oppose the use of, or threats to use, nuclear weapons.” Although China stonewalled the Trump administration’s efforts to launch a formal trilateral arms control process, it is worth exploring whether the heightened tensions of the past year could provide an opening for engagement on a modest risk reduction agenda.

There are other important issues at the intersection of evolving technologies and nuclear risk to be explored bilaterally and multilaterally. Understanding and mitigating cyberrisks to nuclear command and control and warning systems are critical. Russia and the United States are probably best equipped to begin this dialogue on a bilateral basis and to develop norms and rules of the road, but China should be encouraged to join as soon as possible. Similarly, military activities in space and the risk and benefits of artificial intelligence are ripe for inclusion in a wide-ranging and in-depth strategic stability dialogue with China and Russia, among others.

Strategic Arms Control

Despite China’s projected nuclear expansion over the next 10 to 15 years, there is time and need for additional Russian-U.S. bilateral steps. A prerequisite is resuming full implementation of New START, including on-site inspections. Even if the parties do not return to full implementation of New START or the treaty expires, at some point strategic logic will compel them to seek to restore mutual limits on their strategic nuclear forces. Be it in six months, two years, or longer, they will need to resume discussions on maintaining mutual restraints on strategic nuclear forces after New START expires and including additional types of Russian and U.S. nuclear weapons and delivery vehicles in future agreements, recognizing that success likely will require progress across a broader set of strategic capabilities. Even with hostilities in Ukraine, the imperative to manage nuclear risks necessitates Russian-U.S. cooperation on nuclear arms control.

Negotiations on a new treaty or other agreement to succeed New START will not be easy. The United States wants to include all the categories of weapons that the treaty limits plus Russia’s new novel strategic nuclear systems and places a high priority on adding nonstrategic nuclear warheads.8 Russia has a long-standing interest in constraining U.S. long-range conventional strike capabilities and missile defenses and is not keen to accept limits on nonstrategic nuclear weapons or an intrusive new regime for warhead verification. Military activities in outer space, cybercapabilities, and other factors affecting strategic stability also will influence each side’s thinking. Lessons drawn from the war in Ukraine and an apparent growing disconnect between the Kremlin and the Russian ministries of foreign affairs and defense could further complicate if not impede negotiations.

Negotiations on a new treaty or other agreement to succeed New START will not be easy. The United States wants to include all the categories of weapons that the treaty limits plus Russia’s new novel strategic nuclear systems and places a high priority on adding nonstrategic nuclear warheads.8 Russia has a long-standing interest in constraining U.S. long-range conventional strike capabilities and missile defenses and is not keen to accept limits on nonstrategic nuclear weapons or an intrusive new regime for warhead verification. Military activities in outer space, cybercapabilities, and other factors affecting strategic stability also will influence each side’s thinking. Lessons drawn from the war in Ukraine and an apparent growing disconnect between the Kremlin and the Russian ministries of foreign affairs and defense could further complicate if not impede negotiations.

The most immediate priority should be to avoid a situation in which Russian and U.S. strategic arsenals are entirely unconstrained after 2026. This can and should be done even as dialogue on other issues affecting strategic stability between these two countries and perhaps China are proceeding in parallel and at a different pace. For a successor 10-year Russian-U.S. agreement, retaining the New START limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads should be adequate for the United States to deter Russia and China, recognizing that concerns about China’s nuclear expansion make significant Russian-U.S. reductions below New START levels unlikely. A successor agreement should retain limits and verification on intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and heavy bombers covered by New START; include new kinds of strategic systems being pursued by both sides; and potentially include all strategic-range conventional prompt global-strike systems.9

Arms control agreements, particularly the next one with Russia, should be used to encourage each side to adopt more stabilizing nuclear force postures that reduce the risk of nuclear use and the pressure on leaders to launch nonsurvivable nuclear forces early in a crisis. For example, the United States should seek to ban the deployment of the novel Russian systems named Poseidon, a nuclear-powered, nuclear-tipped torpedo, and Burevestnik, a nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed subsonic cruise missile, which are high-risk nuclear doomsday systems prone to catastrophic accident or miscalculation. Such a ban would be similar to prohibitions in the original Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty on deploying strategic nuclear systems undersea or using other exotic basing and delivery modes.

An agreement could limit or ban strategic-range hypersonic vehicles that due to speed and unpredictable flight paths reduce decision time for leaders. It could reinstate a ban on silo-based ICBMs with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) or limit the number of nuclear warheads permitted on each missile, reducing the incentive to “use them or lose them” in a crisis. Deemphasizing ICBMs with MIRVs could set a stabilizing precedent for the future direction of China’s expanding ICBM force. The next treaty also should employ more accurate counting rules for nuclear warheads attributed to heavy bombers, which could lead to a real reduction in the number of each side’s nuclear weapons and a more stringent limit on their nuclear delivery capacity.10

Nonstrategic Nuclear Warheads

The United States and its European allies are keenly interested in limiting Russia’s nonstrategic nuclear weapons given Russia’s larger stockpile, the weapons’ proximity to Europe, and their potential for early use in a conflict, leading to escalation. When the U.S. Senate ratified New START, it called for negotiations with Russia on nonstrategic nuclear weapons, which the Obama and Trump administrations attempted without success due to Russian disinterest. NATO and U.S. interest in limiting these weapons systems has been heightened by Russian nuclear threats during the Ukraine conflict.

Despite the importance of the task, it will not be easy to address this category of weapons systems. Russia and the United States do not have shared objectives, their nuclear stockpiles and operational practices are asymmetrical, there are significant national security sensitivities, and verification will be challenging. Limiting Russian nonstrategic nuclear weapons may require trade-offs across other arms control and strategic stability concerns. At a minimum, progress likely will need to come in the context of reengagement on a broader range of issues affecting strategic stability, such as missile defense and long-range conventional strike capabilities.

One approach could be to address nonstrategic nuclear weapons and nondeployed nuclear warheads together by limiting total nuclear warhead stockpiles with a sublimit on deployed strategic warheads and freedom for each side to determine the breakdown of nonstrategic and nondeployed nuclear weapons. Just as the United States has been concerned with Russia’s numerical advantage in nonstrategic nuclear weapons, which are not deployed on a daily basis, Russia has expressed concern about the greater capacity of the United States to upload additional nondeployed nuclear warheads on its strategic delivery systems. This total stockpile approach would permit trade-offs to address each side’s concerns.

There are other options for addressing this weapons category. As a precursor to more ambitious agreements to limit and verify warhead stockpiles, Russia and the United States could agree to increase mutual transparency through exchanges of information about numbers, types, and locations of total warhead stockpiles, including nonstrategic nuclear weapons.

In a more ambitious approach, the two countries could agree to consolidate nuclear warheads at central storage sites away from operational bases in and near Europe west of the Urals with appropriate verification. This move could reduce the risk of short-warning nuclear attacks using not only tactical systems but also intermediate-range missiles that are no longer banned because the United States withdrew from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in 2019 in response to Russia’s violation of the treaty. For instance, such a consolidation agreement could require Russia to remove nuclear warheads from storage sites associated with operational bases near its western border, including in Kaliningrad, in exchange for the United States, in consultation with NATO allies, agreeing to remove its nonstrategic nuclear weapons from bases in Europe.

With the termination of the INF Treaty, there are no longer any constraints on nuclear-capable short- and intermediate-range land-based ballistic and cruise missiles, those having ranges of 500 to 5,500 kilometers.11 Just as the Cuban missile crisis led to new arms control agreements between the Soviet Union and the United States, an eventual end to the war in Ukraine may create opportunities to rebuild the security architecture in Europe.

With the termination of the INF Treaty, there are no longer any constraints on nuclear-capable short- and intermediate-range land-based ballistic and cruise missiles, those having ranges of 500 to 5,500 kilometers.11 Just as the Cuban missile crisis led to new arms control agreements between the Soviet Union and the United States, an eventual end to the war in Ukraine may create opportunities to rebuild the security architecture in Europe.

High on the agenda should be a verifiable agreement by Russia and the United States to ban missiles previously covered by the INF Treaty in Europe west of the Urals. Although negotiating a stand-alone ban would be the most direct path toward reestablishing a prohibition on these missiles in the Euro-Atlantic region, prohibiting or limiting this missile class within a New START successor agreement should also be considered. The United States should consult urgently with NATO on such an agreement, to potentially include transparency measures at missile defense sites in Romania and Poland to rebuff Russian assertions that the United States might deploy offensive missiles in place of missile defense interceptors located there.

Dialogue With China

Although decades of experience provide a blueprint for Russian-U.S. engagement on nuclear issues, no comparable foundation exists with China. The United States will have to adopt a more incremental approach to China on the basis of a shared interest in reducing nuclear risks and forestalling a dangerous arms race. Despite growing distrust between Beijing and Washington, neither wants a nuclear conflict, but the absence of dialogue fuels worst-case planning on both sides.

The greatest risk is miscalculation or miscommunication, particularly in a regional conflict, leading to unintended escalation and potential nuclear use. Without proactive efforts to change this dynamic, there is a growing likelihood of a nuclear arms race between the two countries with broader implications for stability between Russia and the United States and even between China and Russia.

Dialogue is an essential first step toward transparency and confidence-building measures as initial goals and eventually toward arms control agreements. Improving mutual understanding of each other’s security perceptions and concerns by itself may help shape the trajectory of China’s nuclear expansion. Just as the pace of Chinese nuclear development has accelerated in recent years, it could change again in the future, for better or worse, presumably influenced in part by the Chinese-U.S. relationship.

Beginning a dialogue on nuclear issues and agreeing on its scope will be challenging. U.S. policymakers are concerned by the opaque nature of Chinese nuclear plans, but leaders in Beijing perceive a narrow focus on nuclear weapons as a U.S. attempt to entrench the current numerical disparity and disadvantage China by seeking increased transparency about its much smaller nuclear force. Conversely, Washington perceives Beijing’s resistance to discussing Chinese nuclear weapons as a way to pursue nuclear competition without adopting the transparency and confidence-building measures that have contributed to strategic stability between Russia and the United States.

Beginning a dialogue on nuclear issues and agreeing on its scope will be challenging. U.S. policymakers are concerned by the opaque nature of Chinese nuclear plans, but leaders in Beijing perceive a narrow focus on nuclear weapons as a U.S. attempt to entrench the current numerical disparity and disadvantage China by seeking increased transparency about its much smaller nuclear force. Conversely, Washington perceives Beijing’s resistance to discussing Chinese nuclear weapons as a way to pursue nuclear competition without adopting the transparency and confidence-building measures that have contributed to strategic stability between Russia and the United States.

Establishing an effective dialogue will require an agenda that is broad enough to include the issues and capabilities that each side perceives as having strategic impact but leave to other appropriate bilateral channels challenges such as the status of Taiwan and territorial disputes in the western Pacific Ocean. At a minimum, the agenda likely will need to include nuclear capabilities and doctrine; the weaponization of outer space; anti-satellite weapons; long-range conventional strike forces, including hypersonic weapons; offensive cybercapabilities; and missile defense programs and the offense-defense relationship. In addition, talks could address regional developments that directly impact strategic stability considerations, including the North Korean nuclear and missile threat and its connection to U.S. missile defense capabilities, which China perceives as potentially undermining its second-strike capability.

At the outset, the goal should be for each side to have a better understanding of the other’s security concerns and perceptions and their influence on policy and capabilities choices. This dialogue could provide a foundation for modest measures, such as a bilateral agreement for advance notification of ballistic missile launches, to reduce the risk of misunderstanding or unintended escalation in response to false warnings. Beijing and Washington also should work toward establishing nuclear risk reduction centers on both sides to serve as a means of quick, reliable communication on select strategic and military issues.

Given both countries’ obligations under Article VI of the NPT and their respective security interests, the longer-term agenda should include discussion of capping and reducing nuclear arsenals. U.S. policymakers should begin thinking now about formulations for stopping and reversing a nuclear arms race before the size of China’s arsenal approaches that of the United States and Russia. This could include an agreement by China, France, and the UK not to exceed a certain number of warheads so long as Russia and the United States agree on a New START successor agreement and other commitments aimed at addressing key Chinese and U.S. security concerns.12

The Risk of a Trilateral Nuclear Arms Race

With Russia’s aggression and renewed hostility in Europe, Moscow’s suspension of New START, the treaty’s expiration in three years, and China’s nuclear expansion plans and tense relations with the United States, U.S. nuclear policy, posture, and arms control are at a crossroads. Although some experts believe these trends necessitate a near-term expansion of the U.S. nuclear arsenal, there is time to pursue a more stabilizing outcome with Russia and China. Strengthening and extending the 77-year taboo against the use of nuclear weapons will require renewed efforts to mutually limit and reduce nuclear stockpiles and delivery systems and the salience of nuclear weapons, while addressing other military capabilities affecting regional and global strategic stability.

None of these objectives can be achieved by engaging in a nuclear arms race with multiple countries. The U.S. national security posture and that of its allies and partners would be better served by diplomatic efforts to constrain the nuclear arsenals of its adversaries and competitors using a combination of proven tools and new approaches. Doing so will require a sober assessment of the security challenges facing the United States, the contributions and limits of nuclear weapons in assuring security, and realistic strategies for managing and reducing mutual nuclear risks with China and Russia. The obstacles are formidable, but the U.S. priority must be averting the alternative of a dangerous arms race in a complicated and unpredictable world of three near-peer nuclear competitors.

ENDNOTES

1. Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “Status of World Nuclear Forces,” Federation of American Scientists, n.d., https://fas.org/issues/nuclear-weapons/status-world-nuclear-forces/ (accessed February 9, 2023); U.S. Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, 2022: Annual Report to Congress,” n.d., https://media.defense.gov/2022/Nov/29/2003122279/-1/-1/1/2022-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF. Four other states with nuclear weapons, none of which are parties to the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, are estimated to have nuclear arsenals of 160 (India), 90 (Israel), 20 (North Korea), and 165 (Pakistan). Kristensen and Korda, “Status of World Nuclear Forces.”

2. U.S. Department of State, “Report to Congress on Implementation of the New START Treaty,” n.d., https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2022-New-START-Implementation-Report.pdf.

3. President Putin’s speech and a subsequent statement from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs were silent on whether Russia would continue with the treaty-mandated exchange of data and notifications. See “Foreign Ministry statement in connection with the Russian Federation suspending the Treaty on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (New START),” February 21, 2023, https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/1855184/.

4. U.S. Department of Defense, “2022 Nuclear Posture Review,” October 27, 2022, p. 4, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF#page=40.

5. U.S. Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, 2022: Annual Report to Congress,” pp. 94–100.

6. U.S. Defense Department, “2022 Nuclear Posture Review,” p. 17.

7. Eric S. Edelman and Franklin C. Miller, Statement before the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee on U.S. nuclear strategy and policy, September 20, 2022, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Edelman-Miller%20Opening%20Statement%20SASC%20Hearing%20Sept.%2020%2020226.pdf.

8. Russian and U.S. nuclear weapons stockpiles are roughly comparable numerically, but they are configured differently, and Russia has slightly greater numbers. Both countries are in compliance with the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) limit of 1,550 warheads on deployed strategic delivery vehicles. Beyond that, Russia is believed to have 1,000–2,000 nonstrategic nuclear weapons. The United States has several thousand nondeployed nuclear warheads, but only a small fraction of those is associated with nonstrategic aircraft based in Europe.

9. New START and all previous strategic nuclear arms control treaties with Russia have limited and counted all warheads (or reentry vehicles) attributed to intercontinental ballistic missiles and submarine-launched ballistic missiles as nuclear warheads, regardless of whether they actually are nuclear. Applying this counting rule to all strategic-range delivery systems that are subject to a new agreement would help to address the concern that even conventionally armed, strategic-range, fast-flying, highly accurate systems, such as ballistic or cruise missiles or new hypersonic vehicles, have strategic effect and should be limited because they put at risk the nuclear forces and command and control and warning systems of the other side.

10. New START counts each heavy bomber as having just one nuclear warhead, when in fact Russian and U.S. bombers can carry up to 16 nuclear bombs or cruise missiles. For more detail on possible elements of a New START successor agreement, see Lynn Rusten, “Next Steps on Strategic Stability and Arms Control With Russia,” in U.S. Nuclear Policies for a Safer World, June 2021, pp. 13–21, https://media.nti.org/documents/NTI_Paper_U.S._Nuclear_Policies_for_a_Safer_World.pdf.

11. The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty was terminated in August 2019 following the U.S. determination, which was denied by Russia, that Russia violated the treaty by deploying a land-based intermediate-range, nuclear-capable cruise missile, the 9M729. After the Trump administration withdrew the United States from the treaty, it began the development of new missiles that would have been covered by the treaty for possible deployment in Europe or Asia, saying they would be conventionally armed. Russia has proposed to the United States and NATO a moratorium on deploying this class of missiles in Europe and, although not conceding that the 9M729 missile would have been covered by the treaty, seemingly offered to include that missile in the moratorium.

12. For more detail on possible confidence-building measures China and the United States could take to address key concerns, see James McKeon and Mark Melamed, “Engaging China to Reduce Nuclear Risks,” in U.S. Nuclear Policies for a Safer World, June 2021, pp. 36–46, https://media.nti.org/documents/NTI_Paper_U.S._Nuclear_Policies_for_a_Safer_World.pdf.