Volume 12, Issue 3, March 19, 2020

The projected cost to sustain and upgrade the U.S. nuclear arsenal continues to grow. And grow. And grow some more. The Trump administration’s fiscal year 2021 budget request released in February reinforces what has long been forewarned: The administration’s excessive strategy to replace nearly the entire U.S. nuclear arsenal at roughly the same time is a ticking budget time bomb, even at historically high levels of national defense spending.

“I am concerned that … we have underestimated the risks associated with such a complex and time-constrained modernization and recapitalization effort,” Adm. Charles Richard, the head of U.S. Strategic Command, told the Senate Armed Services Committee on Feb. 13.

Vice Adm. Johnny Wolfe, the director of the Navy strategic systems programs, put it even more bluntly to the House Armed Services Committee on March 3. There is a “pervasive and overwhelming risk carried within the nuclear enterprise as refurbishment programs face capacity, funding, and schedule challenges,” he said.

Adm. Richard and Vice Adm. Wolfe support the administration’s modernization approach and believe that delays to the effort could undermine the U.S. nuclear deterrent. But their warnings should prompt renewed questions about whether the spending plans are necessary and sustainable. The need for a fundamental reassessment is magnified by the rising human and financial toll that the novel coronavirus is inflicting on the national economy. The threat to worker safety and health posed by the disease could exacerbate the execution challenges identified by Adm. Richard and Adm. Wolfe.

Last year, Congress supported the administration’s nuclear budget priorities despite strong opposition from the Democratic-led House. But the costs and opportunity costs of the plans are real and growing – and the biggest modernization bills are just beginning to hit. Scaling back the proposals for new delivery systems, warheads, and their infrastructure would make the nuclear weapons modernization effort easier to execute and save scores of billions of taxpayer dollars that should be spent on addressing higher priority national and health security challenges. Such adjustments would still leave ample funding to sustain a devasting U.S. nuclear deterrent.

The Fiscal Year 2021 Nuclear Budget Request

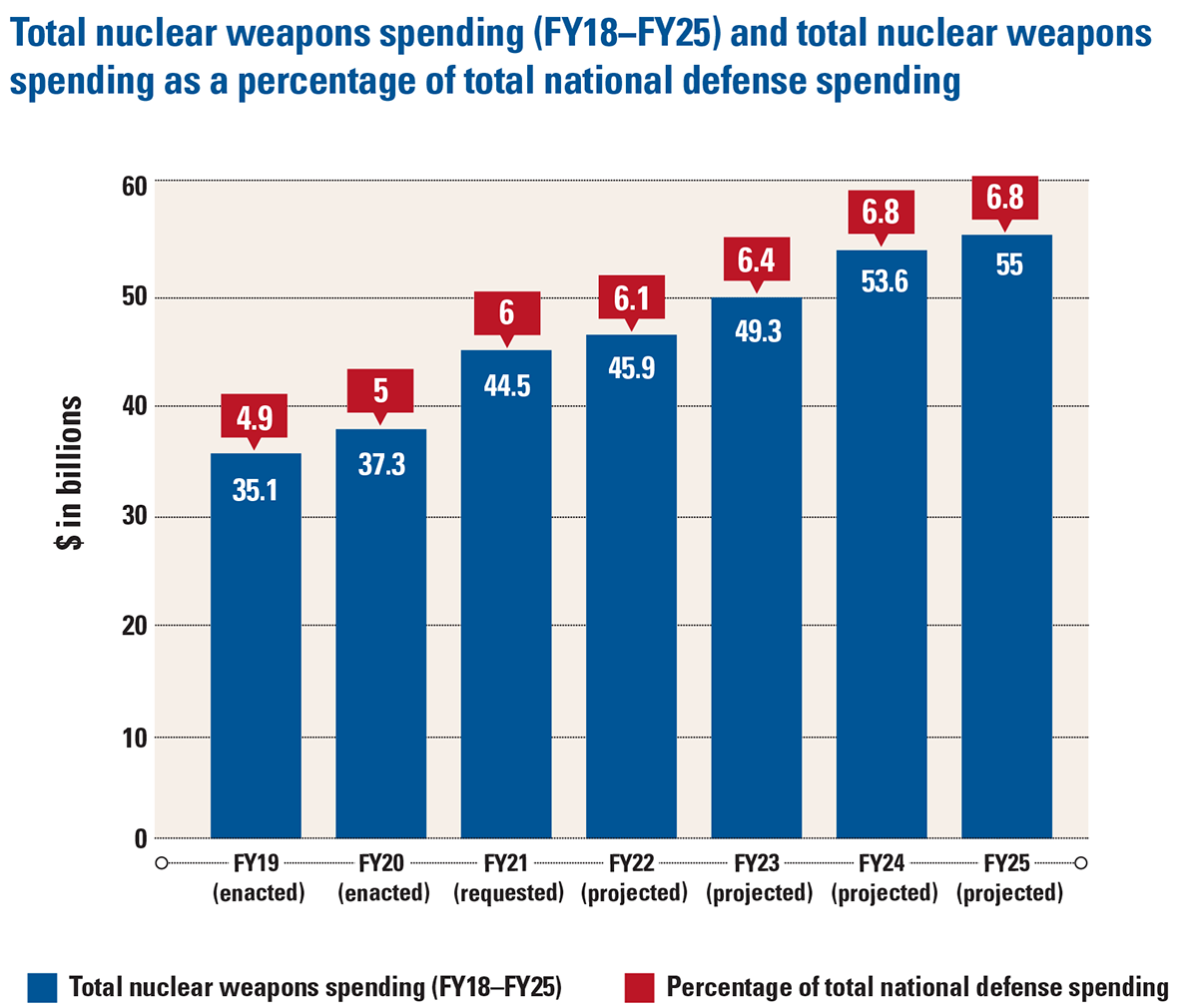

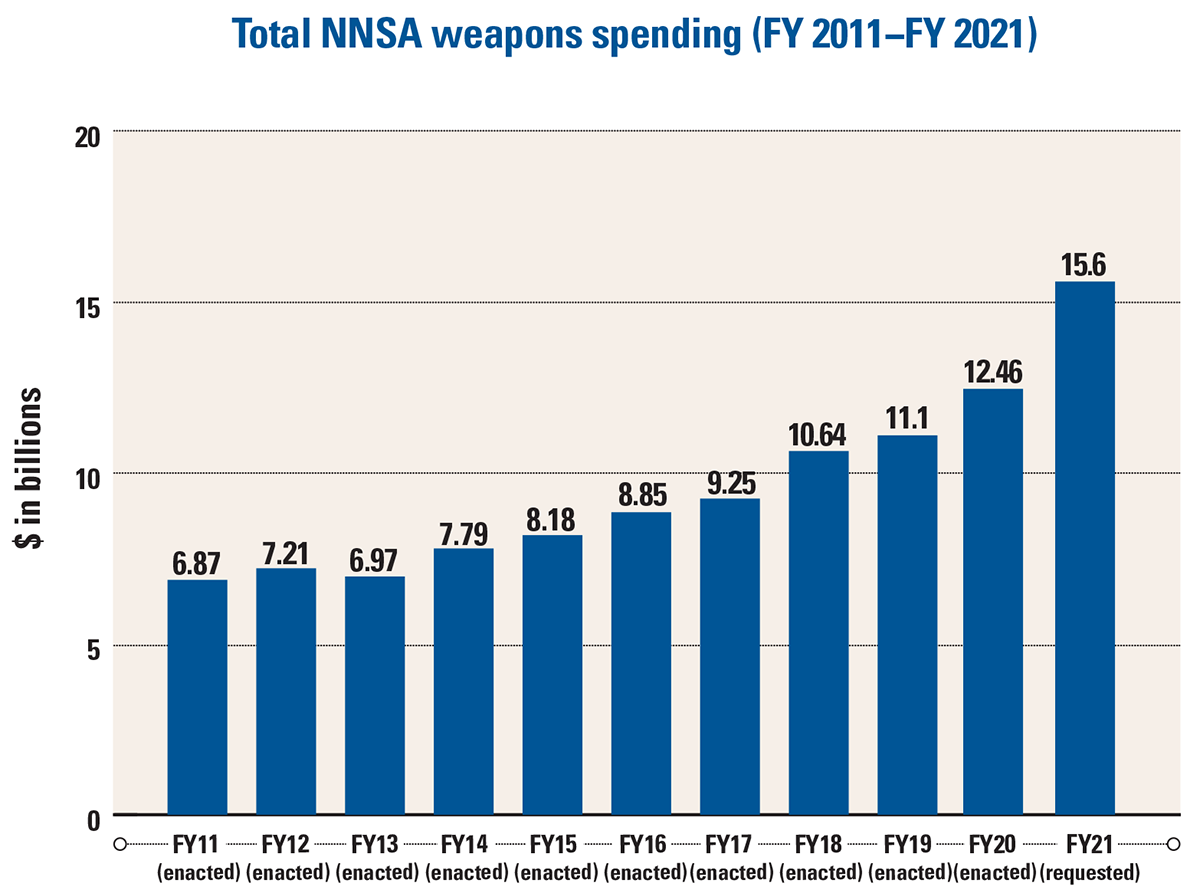

The administration is requesting $44.5 billion in fiscal year 2021 for the Defense and Energy Departments to sustain and modernize U.S. nuclear delivery systems and warheads and their supporting infrastructure, a larger-than-anticipated increase of about $7.3 billion, or 19 percent, from the fiscal year 2020 level. This includes $28.9 billion for the Pentagon and $15.6 billion for the Energy Department’s semiautonomous National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA).

The proposed spending on nuclear weapons constitutes about 6 percent of the total national defense request, up from about 5 percent last year. By 2024, projected spending on the nuclear arsenal is slated to consume 6.8% of total national defense spending. The percentage will continue to rise through the late-2020s and early-2030s when modernization spending is slated to peak.

The proposed spending on nuclear weapons constitutes about 6 percent of the total national defense request, up from about 5 percent last year. By 2024, projected spending on the nuclear arsenal is slated to consume 6.8% of total national defense spending. The percentage will continue to rise through the late-2020s and early-2030s when modernization spending is slated to peak.

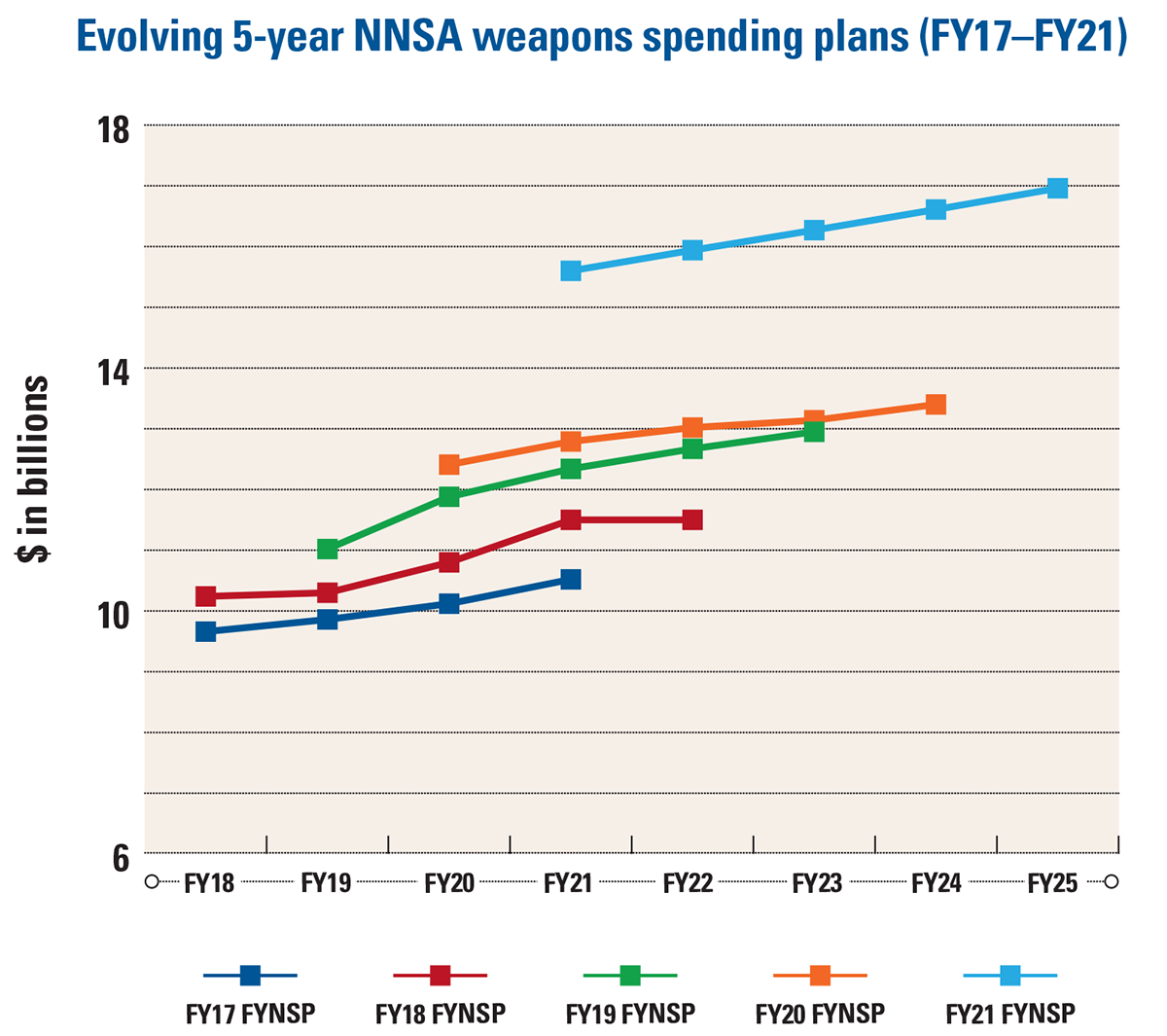

The largest increase sought is for the NNSA nuclear weapons activities account. The budget request calls for $15.6 billion, an astonishing increase of $3.1 billion, or 25 percent, above the fiscal year 2020 appropriation and $2.8 billion above the projection for 2021 in the fiscal year 2020 budget request. Over the next five years, the NNSA is planning to request over $81 billion for weapons activities, a nearly 24 percent increase over what it planned to seek over the same period as of last year.

To put the NNSA weapons activities request in perspective, $15.6 billion is almost twice as much as the $8.3 billion emergency spending bill signed into law March 6 to combat the spread of the novel coronavirus through prevention efforts and research to quickly produce a vaccine for the deadly disease.

The budget request would support continued implementation of the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), which called for expanding U.S. nuclear weapons capabilities. In addition to continuing full speed ahead with the previous administration’s plans to upgrade the arsenal on a largely like-for-like basis, the Trump administration proposed to develop two new sea-based low-yield nuclear options (one of which it has already begun deploying) and lay the groundwork to grow the size of the warhead stockpile.

The budget request would support continued implementation of the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), which called for expanding U.S. nuclear weapons capabilities. In addition to continuing full speed ahead with the previous administration’s plans to upgrade the arsenal on a largely like-for-like basis, the Trump administration proposed to develop two new sea-based low-yield nuclear options (one of which it has already begun deploying) and lay the groundwork to grow the size of the warhead stockpile.

The projected long-term cost of the proposed nuclear spending spree is even more staggering. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected last year that the United States is poised to spend nearly $500 billion, after including the effects of inflation, to maintain and replace its nuclear arsenal between fiscal years 2019 and 2028. This is an increase of nearly $100 billion, or about 23 percent, above the already enormous projected cost as of the end of the Obama administration. Over the next 30 years, the price tag is likely to top $1.5 trillion and could even approach $2 trillion.

These big nuclear bills are coming due as the Defense Department is seeking to replace large portions of its conventional forces and must contend with internal fiscal pressures, such as rising maintenance and operations costs. In addition, external fiscal pressures, such as the growing national debt and the significant economic contraction caused by the coronavirus pandemic, are all likely to limit the growth of – and perhaps reduce – military spending. Indeed, the Trump administration is recommending a lower national defense budget top line in fiscal year 2021 than Congress provided last year.

“The Pentagon must come to terms with the reality that future defense budgets are likely to be flat, which will force leaders to make some tough choices,” Defense Secretary Mark Esper said on Feb. 6.

The costs and risks of the Trump administration’s nuclear weapons spending plans are compounded by its hostility to arms control. The administration withdrew the United States from the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in August 2019 and has shown little interest in extending the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START). If New START expires in February 2021 with nothing to replace it, the incentives for the United States and Russia to grow the size of their arsenals beyond the treaty limits would grow. A new quantitative arms race would cause the already high costs of the modernization effort to soar even higher.

Triad Budget Rises as Planned

The budget request contains large but planned increases to maintain the schedule of Pentagon programs to sustain and rebuild the U.S. triad of nuclear-armed missiles, submarines, and bombers.

The request includes $4.4 billion for the Navy program to build 12 Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). The Air Force is seeking $2.8 billion to continue development of the B-21 Raider strategic bomber, $500 million for the long-range standoff weapon program to replace the existing air-launched cruise missile, and $1.5 billion for the program to replace the Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile with a missile system called the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD). The Pentagon is also asking for $4.2 billion to sustain and upgrade nuclear command, control, and communications systems.

Collectively, the request for these programs is an increase of $3.2 billion, or more than 30 percent, above the fiscal year 2020 level.

Over the next five years, the Pentagon is projecting to request $167 billion to sustain and modernize delivery systems and their supporting command and control infrastructure. The Columbia-class, GBSD, and B-21 programs could each cost between $100-$150 billion after including the effects of inflation and likely cost overruns, easily putting them among the top 10 most expensive Pentagon acquisition programs.

NNSA Budget Explodes

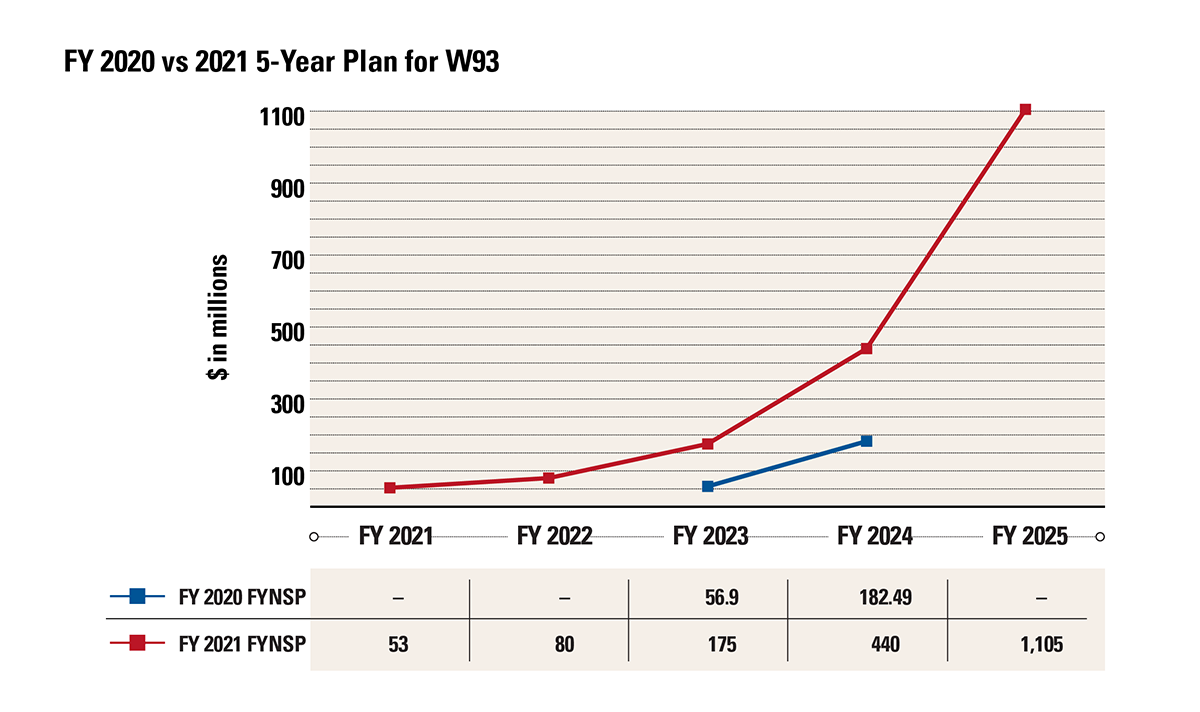

The NNSA budget submission includes large unplanned cost increases for several ongoing warhead life extension programs, the acceleration of the W93 program to develop a newly-designed submarine-launched ballistic missile warhead, the expansion of the production of plutonium pits for nuclear warheads to at least 80 per year, and other large infrastructure recapitalization projects.

The factors driving the NNSA to request such large unplanned increases are unclear. The agency said last year that its fiscal year 2020 budget plan was “fully consistent” with the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review and “affordable and executable.” Under that proposal, the NNSA did not plan to request more than $15 billion for the weapons activities account until 2030.

Several major ongoing programs would reportedly be delayed in the absence of the increase, which would suggest that they have encountered cost overruns.

It is unlikely that the NNSA will be able to spend such a large increase in one year. Allison Bawden, a director at the Government Accountability Office (GAO), told the House Armed Services Committee on March 3 that spending the requested amount “will be very challenging.” This view is supported by the fact that the weapons activities account is sitting on approximately $5.5 billion in unspent carryover balances from previous years.

Despite massive budget increases since the Trump administration took office, the executability of NNSA’s plans is highly questionable. The ambition of the agency’s modernization program is unlike anything seen since the Cold War. Bawden noted that the GAO is “concerned about the long-term affordability of the plans.” Former NNSA administrator Frank Klotz said in a January 2018 interview before the release of the Nuclear Posture Review that the agency was already “working pretty much at full capacity.”

According to Bawden, the tightly coupled nature of the NNSA’s modernization program is such that “any delay could have a significant cascading effect on the overall effort.” The agency has consistently underestimated the cost and schedule risks of major warhead life extension programs and infrastructure recapitalization projects. An independent assessment published last year found “no historical precedent” for the NNSA’s plan to produce 80 plutonium pits per year by 2030. The assessment also stated that the agency had never completed a major project costing more than $700 million in fewer than 16 years.

Moreover, while the NNSA’s five-year spending projection sustains the enormous fiscal year 2021 funding proposal, outyear funding is slated to grow at a set rate of 2.1 percent. In other words, the outyear projections aren't based on what NNSA believes it will actually need. Several major NNSA efforts, such as developing a warhead for a new sea-launched cruise missile and the full scope of the plutonium pit production and uranium enrichment recapitalization plans, are not yet part of the budget. In sum, if "past is precedent," the outyear projections will exceed growth with inflation.

Moreover, while the NNSA’s five-year spending projection sustains the enormous fiscal year 2021 funding proposal, outyear funding is slated to grow at a set rate of 2.1 percent. In other words, the outyear projections aren't based on what NNSA believes it will actually need. Several major NNSA efforts, such as developing a warhead for a new sea-launched cruise missile and the full scope of the plutonium pit production and uranium enrichment recapitalization plans, are not yet part of the budget. In sum, if "past is precedent," the outyear projections will exceed growth with inflation.

Nuclear Force Modernization Cannibalizes Conventional Military Modernization

The damaging opportunity costs of the administration’s decision to prioritize nuclear weapons are on full display in the budget request. The Navy has long been warning that the planned recapitalization of the ballistic missile submarine force will pose a particularly significant affordability challenge. The request includes funding to purchase the first submarine in the class over the next three years.

“[W]e must begin a 40-year recapitalization of our [SSBN] force,” Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas Modly wrote in a Feb. 18 memo directing the Navy to identify $40 billion in savings over the next five years. “This requirement will consume a significant portion of our shipbuilding budget in the coming years and squeeze out funds we need to build a larger fleet.”

The Navy is requesting $19.9 billion for shipbuilding in fiscal year 2021, a decrease of $4.1 billion below the fiscal year 2020 level.

The shipbuilding budget also paid the price for the enormous unplanned increase for the NNSA. The agency’s budget submission was reportedly a controversial issue within the Trump administration and was not resolved until days before the Feb. 10 public release of the budget. President Trump ultimately signed off on adding over $2 billion to the NNSA’s weapons activities account, forcing a late scramble to make room for the additional funding.

Though the Pentagon has not confirmed the exact amount that was taken to pay for the increase, members of Congress and media reports indicate that the increase for the NNSA prevented the Navy from adding a second Virginia-class attack submarine to the shipbuilding budget. The decision to cut an attack submarine to pay for a budget increase the NNSA said last year it didn’t need is hard to square with the Pentagon’s top overall defense priority of preparing for great power competition with China.

Nuclear Weapons Aren’t Cheap

The Pentagon argues that even at its peak in the late-2020s, spending on nuclear weapons is affordable because it will consume a peak of roughly 6.4 percent of total Pentagon spending in 2029. But this figure is misleading for several reasons. For starters, the figure doesn’t include spending at the NNSA. When NNSA spending is included, nuclear weapons already account for 6 percent of the total FY 2021 national defense budget request. Regardless, even 6 percent of a budget as large as the Pentagon’s is an enormous amount of money. By comparison, the March 2013 congressionally mandated sequester reduced national defense spending (minus exempt military personnel accounts) by 7 percent. Military leaders and lawmakers repeatedly described the sequester as devastating.

Meanwhile, a better measure of the opportunity costs of prioritizing nuclear modernization is to compare spending on that modernization to overall Defense Department acquisition spending. The Pentagon is requesting $17.7 billion for nuclear weapons research, development, and procurement in fiscal year 2021. This amount already accounts for 7.3 percent of the total requested Pentagon acquisition spending. While the Pentagon is projecting a decline in total acquisition spending over the next five years, nuclear acquisition spending is primed for a major increase. The CBO estimated in 2017 that by the early 2030s, spending on nuclear weapons would rise to 15 percent of the Pentagon’s total acquisition costs.

Pentagon officials also repeatedly claim that unless they get every penny that they are asking for to modernize the arsenal, the arsenal will begin to erode into obsolescence. But this is a false choice. The right question is whether the administration’s approach is necessary, sustainable, and safe, especially in the absence of any negotiated restraints on the U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals. And the right answer is that the administration’s current path is unnecessary, unsustainable, and unsafe – and must be rethought.

Recommendations for Congress

The bottom line is that Trump administration’s nuclear weapons spending plans cannot be sustained without significant and sustained increases to defense spending – which are unlikely to be forthcoming – or cuts to other security priorities. The current approach is a costly and irrational recipe for nuclear modernization program delays and scope reductions.

But while the plans pose significant challenges, they need not prevent the United States from continuing to field a powerful and credible nuclear force sufficient to deter or respond to a nuclear attack against the United States and its allies. The administration inherited a larger and more diverse nuclear arsenal than is required for deterrence and its approach to modernization and arms control would increase the risks of miscalculation, unintended escalation, and accelerated global nuclear competition.

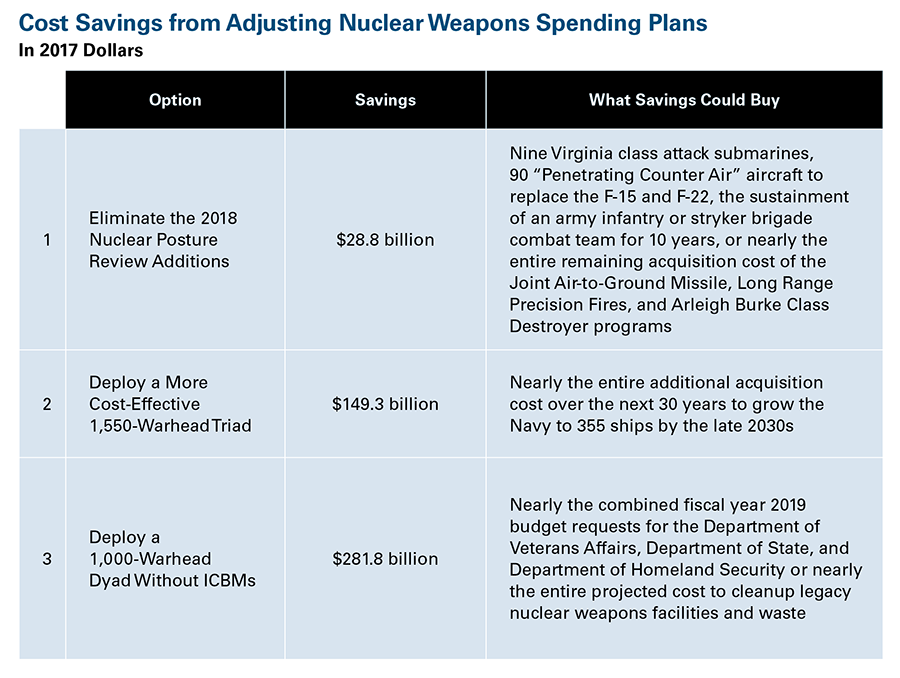

Instead, the United States could save at least $150 billion in fiscal year 2017 constant dollars through the mid-2040s by adjusting the current modernization approach while still retaining a triad and deploying the New START limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads. Such an approach would reflect a nuclear strategy that reduces reliance on nuclear weapons, emphasizes stability and survivability, de-emphasizes nuclear warfighting, reduces the risk of miscalculation, and is more affordable and executable.

Instead, the United States could save at least $150 billion in fiscal year 2017 constant dollars through the mid-2040s by adjusting the current modernization approach while still retaining a triad and deploying the New START limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads. Such an approach would reflect a nuclear strategy that reduces reliance on nuclear weapons, emphasizes stability and survivability, de-emphasizes nuclear warfighting, reduces the risk of miscalculation, and is more affordable and executable.

The options include:

- Buying 10 instead of 12 new Columbia class ballistic missile submarines;

- Extending the life of the existing Minuteman III ICBM instead of building a new missile and reducing the size of the ICBM force from 400 missiles to 300 missiles (for a detailed discussion of the case for this option, see here);

- Foregoing development of new nuclear air- and sea-launched cruise missiles;

- Scaling back plans to build newly-designed ICBM and SLBM warheads;

- Aiming for a pit production capacity of 30-50 pits per year by 2035 instead of at least 80 pits per year by 2030;

- Foregoing development of a new uranium enrichment facility; and

- Retiring the megaton-class B-83 gravity bomb.

Simply reverting to the fiscal year 2020 budget plan for NNSA weapons activities would save over $15.5 billion over the next five years.

Now is the time to re-evaluate nuclear weapons spending plans before the largest investments are made. Of course, pressure on the defense budget cannot be relieved solely by reducing nuclear weapons spending. A significant portion of the overall cost of nuclear weapons is fixed. That said, changes to the nuclear replacement program could make it easier to execute and ease some of the hard choices facing the overall defense enterprise.

In addition to pursuing adjustments to the scope and scale of the modernization program, Congress should also take steps to improve its understanding of the long-term budget challenges. These include:

- Holding in-depth hearings on U.S. nuclear weapons policy and spending;

- Requiring the Defense and Energy Departments to prepare a report on options for reducing the scale and scope of their nuclear modernization plans and the associated cost savings;

- Mandating unclassified annual government updates on the projected long-term costs of nuclear weapons;

- Requiring an independent report on alternatives to building a new ICBM;

- Tasking the GAO to annually assess the affordability of the Defense and Energy Department’s modernization plans; and

- Requiring the NNSA to perform detailed work examining the estimated life of plutonium pits.

Also, lawmakers should more aggressively highlight the relationship between arms control and upgrading the arsenal. The administration’s current one-sided approach both compounds the dangers of the spending plans and flies in the face of longstanding Congressional support for the pursuit of modernization and arms control in tandem.

If the administration continues to insist on nuclear weapons modernization without arms control, then Congress should make it clear that it will not allow the president to increase the size of the arsenal above the New START limits and will be further emboldened to seek to restrain the administration’s excessive and unsustainable spending plans.—Kingston Reif, director for disarmament and threat reduction policy, and Shannon Bugos, research assistant