“For half a century, ACA has been providing the world … with advocacy, analysis, and awareness on some of the most critical topics of international peace and security, including on how to achieve our common, shared goal of a world free of nuclear weapons.”

Trump, Kim Make Nuclear Crisis Personal

October 2017

By Terry Atlas and Kelsey Davenport

Tensions between the United States and North Korea moved into dangerous new territory last month, as two inexperienced national leaders engaged in name-calling backed up by threats of nuclear conflict.

It remains unclear whether the tension that has been increasing for months, as North Korean leader Kim Jong Un defied international pressure to halt his nuclear weapons program, will drive a serious effort for negotiations or trigger, intentionally or by accident, military action that could cause tens or hundreds of thousands of deaths on the Korean peninsula and perhaps beyond.

Complicating matters is the fact that the two key decision-makers, Kim and U.S. President Donald Trump, are untested in such diplomatic crisis situations and have shown tendencies to provoke further confrontation.

Addressing the UN General Assembly on Sept. 19, Trump belittled Kim as “rocket man” and used the podium of the world’s pre-eminent peacemaking institution to threaten to “totally destroy” North Korea if the United States “is forced to defend itself or its allies.” In doing so, the Los Angeles Times reported, Trump ignored appeals from his national security team not to make the situation more dangerous and the path to negotiations more daunting by insulting the young dictator.

Kim quickly responded in kind and, for the first time, personally issued a statement directed at a U.S. president, saying that Trump barks like a “frightened dog” and is a “mentally deranged U.S. dotard,” which is a senile or weak-minded individual.

In a sign of further defiance, North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Yong Ho was quoted Sept. 21 as telling journalists in New York, where he was attending the UN session, that Kim is considering whether to test a hydrogen bomb in the Pacific Ocean, which would be the first atmospheric nuclear test explosion since China conducted one on Oct. 16, 1980.

Ri was likely referring to launching an intercontinental ballistic missile paired with a nuclear warhead into the Pacific Ocean to demonstrate North Korea’s capabilities. That would be a profoundly provocative action, with environmental and health implications from the radioactive fallout, and defy the norm against atmospheric nuclear tests established by the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty.

Trump fired back at Kim using his favored communications weapon, Twitter, writing that “Kim Jong Un of North Korea, who is obviously a madman who doesn’t mind starving or killing his people, will be tested like never before!” Less provocatively, U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said on Sept. 22 on ABC’s “Good Morning America” that “we will continue our efforts in the diplomatic arena, but all our military options are on the table.”

Yet, any military option comes with significant risks, particularly with South Korea’s capital, Seoul, within range of North Korea artillery just north of the Demilitarized Zone, which may dismiss it as a viable solution.

Trump’s former chief strategist, Steve Bannon, told The American Prospect in August, “Until somebody solves the part of the equation that shows me that ten million people in Seoul don’t die in the first 30 minutes from conventional weapons, I don’t know what you’re talking about, there’s no military solution here, they got us.” Defense Secretary Jim Mattis subsequently said, without providing any details, that the United States has military options that would not put Seoul at risk.

The Trump administration has paired its threats with additional sanctions targeting North Korea. Trump issued an executive order Sept. 21 that targets banks and companies that continue to do business with North Korea. U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said that Washington has the tools to “cut off banks from the banking system in the United States.”

“For much too long, North Korea has been allowed to abuse the international financial system to facilitate funding for its nuclear weapons and missile program,” Trump said in announcing the measures.

Significantly, China’s central bank agreed to cooperate and directed financial institutions throughout China to curtail their loans and other business with North Korea and the North Korean government.

In his address to the UN General Assembly on Sept. 23, Ri said it was a “forlorn hope to consider any chance that [North Korea] would be shaken an inch or change its stance due to the harsher sanctions by the hostile forces.” Ri also called out Trump’s “reckless and violent” words and said that, by insulting North Korea, he made the “irreversible mistake of making our rockets’ visit to the entire U.S. mainland inevitable all the more.”

The Trump administration is seeking to use increasing pressure from tightening economic sanctions, influence from China, and the threat of military action to force North Korea to negotiate denuclearization. “It is time for North Korea to realize that the denuclearization is its only acceptable future,” Trump declared in his address to the UN General Assembly.

In recent years, diplomacy has not gained traction. U.S. President Barack Obama tried to use UN Security Council demands and sanctions to increase pressure on North Korea while waiting for Kim Jong Un to take steps toward denuclearization, a policy called “strategic patience.” The Obama administration’s insistence on onerous preconditions and misreading of North Korean signals in favor of talks, however, failed to produce results. (See ACT, March 2015.)

In recent years, diplomacy has not gained traction. U.S. President Barack Obama tried to use UN Security Council demands and sanctions to increase pressure on North Korea while waiting for Kim Jong Un to take steps toward denuclearization, a policy called “strategic patience.” The Obama administration’s insistence on onerous preconditions and misreading of North Korean signals in favor of talks, however, failed to produce results. (See ACT, March 2015.)

As a result, North Korea’s nuclear program raced ahead to produce additional nuclear material for warheads and increasingly powerful missiles. Now, under the Trump administration, North Korea is able for the first time to reach much of the U.S. mainland with its ballistic missiles, although the accuracy and reliability is questionable.

Since taking office, Trump has redoubled sanctions pressures and demanded China step up and said on Aug. 8 that the North would feel the “fire and fury” of the United States if the regime continued its threats and destabilized the Korean peninsula and East Asia. Kim responded with further missile tests and, on Sept. 3, North Korea claimed a hydrogen bomb test vastly more powerful than previous underground tests.

On the diplomatic front, Trump so far has been dismissive of the freeze-for-freeze proposal favored by China and Russia in which North Korea would suspend nuclear and ballistic missile tests and the United States would suspend more provocative elements of its large-scale joint military exercises with South Korea.

Trump may have narrowed his leverage further with his denunciations of the Iran nuclear deal, indicating that he may walk away from that accord and seek to impose new, tougher restrictions on Iran. That may signal to Kim that any deal, even if it is endorsed by the UN Security Council as the Iran deal is, may not be upheld by the United States, meaning that nuclear weapons are needed for regime security. James Clapper, former U.S. director of national intelligence, has said that he does not foresee a scenario in which North Korea relinquishes its nuclear weapons.

That would mean accepting negotiations focused on achieving some level of nuclear arms control and reduced tensions, coupled with U.S. nuclear deterrence policies. If so, Trump may have a choice between becoming the U.S. president who acquiesced to North Korea as a nuclear weapons power or as the U.S. president who went to war to prevent that outcome. Neither of the two U.S. defense treaty allies with the most at risk, South Korea and Japan, seem politically prepared for a serious military conflict with North Korea. —TERRY ATLAS AND KELSEY DAVENPORT

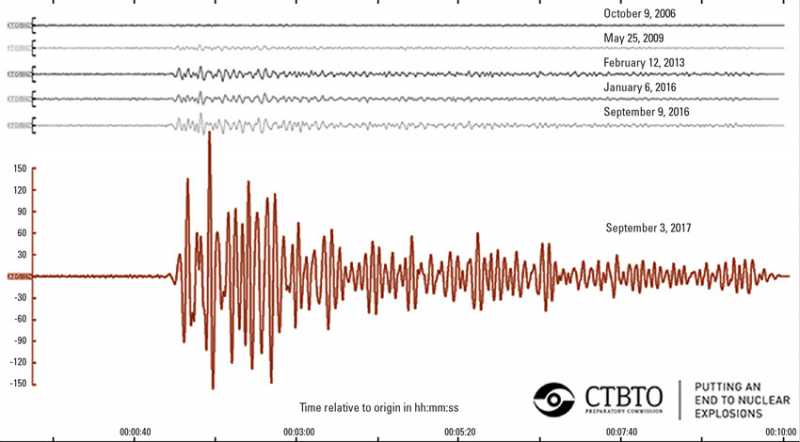

North Korea’s Sixth Test Its Largest Yet The Sept. 3 nuclear test explosion at North Korea’s underground Punggye-ri test site produced a magnitude 6.1 seismic event, according to specialists at the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) International Data Centre (IDC) in Vienna. The analysis was made on the basis of information from 41 primary and 90 auxiliary seismic stations that are part of the CTBTO International Monitoring System (IMS). Signals from the nuclear test were also detected by two hydroacoustic stations and one infrasound station. The IMS consists of 50 primary and 120 auxiliary seismic stations, of which 42 and 107 stations, respectively, are certified. The IDC detected a second event that occurred 8.5 minutes after the initial blast, at approximately the same location, but two units of magnitude smaller. That event, along with a magnitude 3.4 seismic event detected on Sept. 23, have been assessed by the CTBTO and national authorities to have been caused by geologic disturbances created by the Sept. 3 nuclear test explosion. At a magnitude of 6.1, the Sept. 3 nuclear test was by far North Korea’s largest. On Sept. 14, the CTBTO published a chart listing the range of body wave magnitudes and estimates of yield, which ranged from 140 to 450 kilotons TNT equivalent. Such a blast would be roughly 10 to 30 times the strength of the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima, which was about 15 kilotons. The largest previous North Korean nuclear test was in the 20-kiloton range. Analysts Frank V. Pabian, Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., and Jack Liu estimated the yield of the test was roughly 250 kilotons, according to their analysis published in the blog 38 North. North Korea claimed the device was a hydrogen bomb designed to be carried by a long-range missile. Whether such a North Korean device could be fitted into a warhead small enough and light enough for such a missile is not clear, according to Siegfried Hecker, a former director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory. In a Sept. 7 interview in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Hecker said the explosive power of the Sept. 3 blast “was consistent with a hydrogen bomb—that is, a fusion-based bomb. However, it could also have been a large `boosted’ fission bomb, in which the hydrogen isotopes deuterium and tritium were used to enhance the fission yield.” More testing, Hecker said, would make it possible for North Korea to arm a long-range missile with ahigh-yield warhead.—DARYL G. KIMBALL Comparison of Seismic Signals From the Six North Korean Nuclear Tests The Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization's International Data Centre estimates the seismic wave produced by the Sept. 3 explosive nuclear test was equivalent to a magnitude 6.1 earthquake. The seismic signals (shown to scale) of the six declared North Korean nuclear tests, as observed at the International Monitoring System station AS-59 in Aktyubinsk, Kazakhstan, show the latest explosion produced a much higher yield than the previous five tests

|