Hanoi Summit Ends Abruptly: What’s Next?

The second summit between North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and U.S. President Donald Trump ended abruptly on day two without any interim agreement and without clarity about the next steps to advance denuclearization and peacebuilding on the Korean peninsula. Nonetheless, both leaders appear confident that negotiations will continue.

U.S. and North Korean officials offered different explanations for why the two leaders were unable to make any announcements during the Feb. 27-28 Hanoi meetings, which originally included a scheduled signing ceremony. The scope of a deal that exchanged verifiable dismantlement of the Yongbyon nuclear complex for easing sanctions appeared to be the cause of disagreement. But it is unclear if Trump and Kim were unable to resolve gaps that existed before the summit, or if either leader attempted to raise the stakes during the Hanoi meetings.

Trump said in a news conference at the end of the Hanoi summit that North Korea wanted U.S. sanctions lifted “in their entirety” in return for partial denuclearization, so he “had to walk away.” But a senior State Department official, speaking to press Feb. 28, said Trump challenged Kim to “go all in,” implying that Trump may have tried to expand discussions to include nuclear facilities outside of Yongbyon.

North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Yong Ho said in a March 1 news conference that North Korea asked for partial sanctions relief from UN restrictions that “hamper the civilian economy and the livelihood of our people,” in return for dismantlement of Yongbyon under U.S. inspections, as well as a permanent halt to nuclear and ballistic missile testing, but Trump’s demand for “one more measure” was unacceptable. Specifically, Ri said North Korea was looking for relief from sanctions included in five UN Security Council resolutions passed in 2016 and 2017 (see below for details.)

In addition to Yongbyon, opening liaison offices and announcing a declaration ending the Korean War were reportedly on the agenda for the summit.

Despite the abrupt end to the summit, both U.S. and North Korean officials seemed upbeat about the prospect of a future deal and remain committed to talks, although no announcement was made on when the negotiating teams will next meet. Trump said at the Feb. 28 news conference talks would continue and emphasized that he has a “strong partnership” with Kim.

The Korean Central News Agency described the meeting positively in a March 1 piece as “an important occasion for deepening mutual respect and trust” and said both Trump and Kim agreed to “continue productive dialogues for settling the issues discussed at the Hanoi Summit.”

While the United States and North Korea did not announce any new measures, Trump said Kim agreed to continue abiding by its April 2018 moratorium on long-range missile and nuclear tests. The United States also agreed to continue modifying joint military exercises with South Korea and announced March 3 that two annual exercises that North Korea views as provocative, Foal Eagle and Key Resolve, would be terminated.—ALICIA SANDERS-ZAKRE, research assistant, and KELSEY DAVENPORT, director for nonproliferation policy

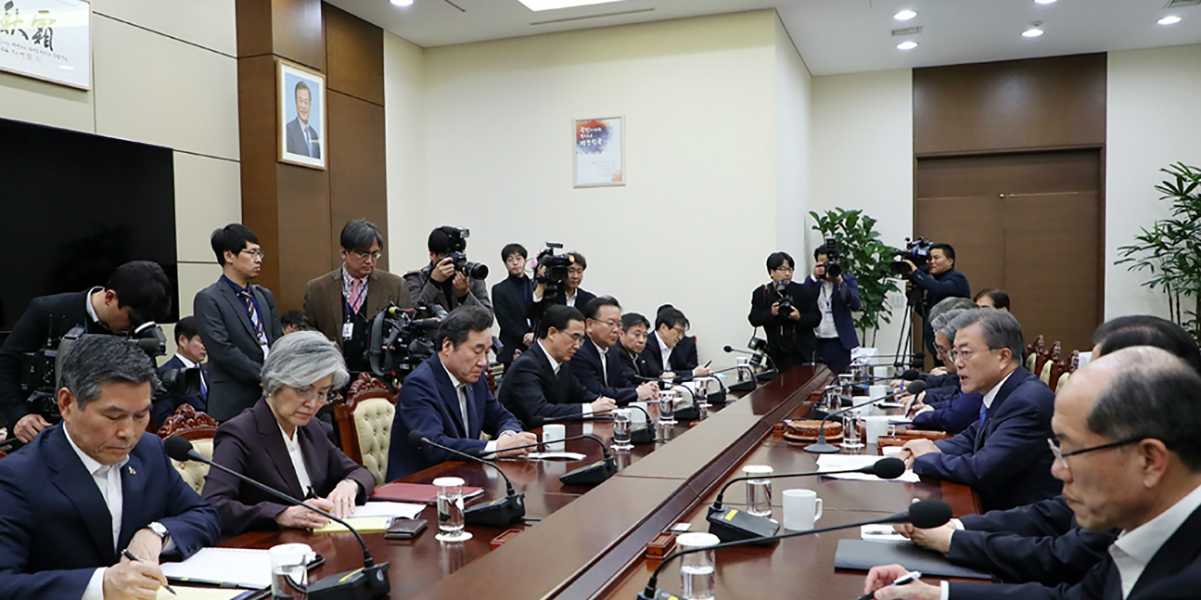

South Korea Pushes for Trilateral Working Group Talks

South Korean President Moon Jae-in said that the Hanoi summit’s failure to produce concrete results was “disappointing,” but he urged both sides to resume negotiations as soon as possible. After a March 4 National Security Council Meeting, Moon reportedly directed South Korean officials to work with the United States and North Korea to bridge the gaps between their negotiating positions on a deal trading verifiable dismantlement of Yongbyon for sanctions relief.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in said that the Hanoi summit’s failure to produce concrete results was “disappointing,” but he urged both sides to resume negotiations as soon as possible. After a March 4 National Security Council Meeting, Moon reportedly directed South Korean officials to work with the United States and North Korea to bridge the gaps between their negotiating positions on a deal trading verifiable dismantlement of Yongbyon for sanctions relief.

South Korea’s Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha said Seoul would “create a venue for the resumption of North Korea-U.S. dialogue,” including working-level meetings involving all three countries.

It is unclear, however, if the United States is still interested in pursuing a deal trading steps to dismantle Yongbyon for limited sanctions relief as a step toward complete, verifiable denuclearization. U.S. Special Envoy Steve Biegun hinted in January that the United States was shifting its negotiating strategy to an incremental approach to denuclearization that put inducements on the table earlier in the process, but statements from U.S. officials following the Hanoi meeting imply that Trump had pressed for a comprehensive agreement.

U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton told CBS March 3 that Trump would not accept an “action for action kind of arrangement” which he claimed was the mistaken approach of previous U.S. administrations. He said Trump offered North Korea “an enormous economic future” if it committed to complete denuclearization, which Bolton claimed would include its ballistic missile program and its chemical and biological weapons programs. North Korea’s refusal to accept “the big deal” and to “try to do something less than that” was “unacceptable” to the United States.

A senior State Department official made a similar comment in a Feb. 28 press briefing, noting that Trump urged Kim to “go bigger” at the Hanoi summit.

The United States has not expressed the same urgency as South Korea to restart working-level talks with North Korea and it is unclear if Washington is interested in South Korea’s participation in the working-level meetings.

“My sense is it’ll take a little while,” U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said Feb. 28 in response to a reporter’s question about when the next working-level meetings would take place. “We’ll each need to regroup a little bit. But we’re hopeful that Special Representative Biegun and that team will get together before too long. But we’ll see.”

Pompeo then told reporters March 4 that he hoped to have a team back in Pyongyang “in the next couple of weeks.”

Meetings between U.S. and North Korean negotiators lagged following the Singapore summit and were only picked up again in the two months leading up to the Hanoi summit, likely contributing to the failure to reach agreement in Hanoi. Sustaining working-level talks between the United States and North Korea following the Hanoi summit will be critical to reach agreement on practical steps forward and avoid another future summit resulting in a lack of agreement.

IAEA Reports North Korea’s Reactor is Not Operating

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Director-General Yukiya Amano reported to the agency’s Board of Governors March 4 that the agency “has not observed any indications of the operation of the 5MW(e) reactor since early December 2018.”

The 5MW(e) reactor, located in the Yongbyon complex, produces plutonium that North Korea reprocesses for its nuclear weapons. Amano also said that the agency has “not observed any indications of reprocessing activities.”

The 5MW(e) reactor, located in the Yongbyon complex, produces plutonium that North Korea reprocesses for its nuclear weapons. Amano also said that the agency has “not observed any indications of reprocessing activities.”

When Amano last addressed the Board of Governors in November, he said that the 5MW(e) reactor was “likely” shut down as North Korea may have been making changes related to its cooling system.

The Yongbyon complex also includes a centrifuge facility for uranium enrichment. Amano said the agency observed “indication of the ongoing use” of that facility but could not confirm the nature or purpose of those activities without access.

Amano said that the IAEA “stands ready to undertake verification and monitoring activities” in North Korea if an agreement is reached.

Congress Reacts to Hanoi Summit

Members of Congress reacting to the Hanoi summit largely welcomed Trump’s decision to walk away from a “bad deal,” although many Democratic members of Congress, while supporting a diplomatic approach, also expressed concern about lack of U.S. preparation going into the summit.

Members of Congress reacting to the Hanoi summit largely welcomed Trump’s decision to walk away from a “bad deal,” although many Democratic members of Congress, while supporting a diplomatic approach, also expressed concern about lack of U.S. preparation going into the summit.

“What we want is denuclearization,” Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) said at her weekly news conference following the summit. “They wanted lifting sanctions without denuclearization. I'm glad that the President walked away from that.”

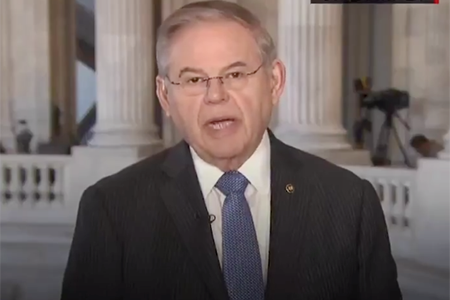

Senate Foreign Relations Committee Ranking Member Bob Menendez (D-N.J.) called the summit “amateur hour” on CNN, adding that it lacked “strategic planning.”

U.S. Senate Democratic Whip Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) said in a statement that he hoped Trump would better appreciate the importance of “doing his homework.” He added, “But there is no other acceptable way to resolve the threat posed to the U.S. and our allies by North Korea, and I hope peaceful attempts to resolve the crisis continue.”

Rep. Eliot Engel (D-N.Y.), chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, stated he was “relieved” that there had been no lifting of sanctions “given there were no major commitments by North Korea about its nuclear program.”

“[T]he president is to be commended for walking away when it became clear insufficient progress had been made on de-nuclearization,” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said in a Feb. 28 statement.

Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Jim Risch (R-ID), concurred, saying in a statement, “I applaud President Trump for rejecting North Korea’s limited offer and for seeking a complete and comprehensive agreement.”

House Foreign Affairs Committee Ranking Member Michael McCaul (R-TX) claimed it is “better to have no deal than agree to a bad one” and encouraged further discussions toward the denuclearization of North Korea.

UN Security Council Issues Waivers for Humanitarian Aid

In the lead up to the Hanoi summit, the UN Security Council sanctions committee granted more than a dozen sanctions waivers for humanitarian aid to North Korea.

The sanctions committee, established by UN Security Council Resolution 1718, granted 10 waivers for humanitarian aid to North Korea in January and three exemptions in February.

The sanctions committee, established by UN Security Council Resolution 1718, granted 10 waivers for humanitarian aid to North Korea in January and three exemptions in February.

One of those waivers was for the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent to deliver 500 bicycles, medical supplies, water purifiers and other equipment necessary for relief activities in North Korea. Waivers for the Swiss Humanitarian Aid and World Vision will help to provide North Koreans with clean drinking water. UNICEF, the Eugene Bell Foundation, Christian Friends of Korea, First Steps Health Society, Handicap International, France, Germany, Ireland, and the World Health Organization also received waivers.

Biegun publicly announced a change in U.S. policy to better support humanitarian aid to North Korea in December 2018 and he reportedly met with NGOs to discuss the implementation of the policy in January.

Inter-Korean Dialogue Continues, But Projects Remain Stalled

The inter-Korean dialogue has continued, but without U.S. sanctions waivers a number of projects Moon and Kim committed to pursuing, including reopening the Kaesong industrial complex, the Kumgang Tourist Zone, and the inter-Korean railway, have stalled. Moon had proposed the United States offer to waive sanctions allowing inter-Korean economic projects to move forward in return for North Korean steps on denuclearization.

South Korea’s efforts to send flu medicine to North Korea also appear to be held up over U.S. sanctions.

Despite the lack of progress on these projects, North and South Korean officials continued to meet over the past month to discuss liaison offices and sports cooperation. Moon said March 4 that the two countries will hold military talks in March and continue to work with the United States to find a path forward on an inter-Korean project requiring sanctions relief.

Backgrounder: UN Security Council Sanctions The UN Security Council passed its first resolution sanctioning North Korea over its nuclear weapons program in 2006, following the country’s first nuclear test. Initial sanctions resolutions targeted North Korean weaponry and luxury goods while more recent sanctions build on these restrictions and add prohibitions on major North Korean exports, like coal, iron, minerals and seafood, and imports, including oil and petroleum products. North Korea’s Foreign Minister Ri Yong Ho said March 1 that Pyongyang proposed verifiable dismantlement of Yongbyon in exchange for the partial lifting of sanctions in five UN Security Council resolutions that hamper the country’s economic development. He was likely referring to sectoral sanctions in the five resolutions passed in 2016 and 2017 in response to North Korean nuclear and missile tests. Below are select provisions from the five most recent UN Security Council resolutions that Ri may have been referring to his description of North Korea’s proposal: UN Security Council Resolution 2270 (2016)

UN Security Council Resolution 2321 (2016)

UN Security Council Resolution 2371 (2017)

UN Security Council Resolution 2375 (2017)

UN Security Council Resolution 2379 (2017)

For more information on each major sanctions resolution on North Korea passed by the UN Security Council since 2006, see our factsheet: “UN Security Council Resolutions on North Korea.” |

New Resources & Analyses

- Michael Elleman, “Why a Formal End to North Korean Missile Testing Makes Sense,” 38 North, Feb. 26, 2019

- Siegfried S. Hecker, Robert L. Carlin, and Elliot A. Serbin, “Comprehensive History of North Korea’s Nuclear Program: 2018 Update,” Center for International Security and Cooperation, Stanford University, Feb. 11, 2019

- Ronald K. Chesser, Joel S. Wit, and Samantha J. Pitz, “A How-To Guide for Disabling and Dismantling Yongbyon,” 38 North, Feb. 15, 2019

- Catherine Killough, “Begun is Half Done: Prospects for U.S.-North Korea Nuclear Diplomacy” The Ploughshares Fund, February 2019