October 2018

By Alan J. Kuperman and Hina Acharya

Facing U.S. diplomatic pressure and the expiration of the initial 30-year term of the 1988 U.S.-Japanese nuclear agreement, the Japan Atomic Energy Commission (JAEC) in late July revealed a plan ostensibly intended to reduce Japan’s massive 47-metric-ton stockpile of unirradiated plutonium by boosting the use of mixed-oxide (MOX) fuel in the country’s nuclear power reactors.

This plan unfortunately would make the problem worse. It also contradicts the findings of a just-published study that the Nuclear Proliferation Prevention Project researched for a year, examining the seven countries, including Japan, that have commercially used or produced MOX fuel for thermal nuclear power plants.1 The research found that five of these countries already have decided to phase out MOX fuel, which is a blend of plutonium with uranium, due to concerns about economics, security, and public acceptance.

This plan unfortunately would make the problem worse. It also contradicts the findings of a just-published study that the Nuclear Proliferation Prevention Project researched for a year, examining the seven countries, including Japan, that have commercially used or produced MOX fuel for thermal nuclear power plants.1 The research found that five of these countries already have decided to phase out MOX fuel, which is a blend of plutonium with uranium, due to concerns about economics, security, and public acceptance.

The JAEC has correctly identified the problem but not the solution. The surplus 47 metric tons of plutonium is sufficient to make more than 5,000 nuclear weapons. Japan is now the only country without such weapons that reprocesses its spent nuclear fuel, creating still more plutonium. Japan even plans to start commercial operation in 2021 of a domestic reprocessing plant that would produce up to an additional eight metric tons of plutonium annually.

All this creates the impression internationally that Japan is preserving the option to quickly produce a large nuclear weapons arsenal. Not surprisingly, South Korea, North Korea, and China have cited Japan’s plutonium stockpile as grounds to initiate or expand their own reprocessing of nuclear fuel, thereby raising the specter of a disastrous nuclear arms race in East Asia.2

The Japanese government was wise to declare a policy to reduce its plutonium stockpile. Yet, the JAEC strategy to do so by increasing the use of MOX fuel in the country’s nuclear power reactors is wrong for at least four reasons: it is impossible to do in the near term, counter-productive, not the quickest way to reduce the stockpile, and unsuitable for most of Japan’s domestic plutonium.

Roots of Japan’s Stockpile

Before discussing the flaws of the JAEC plan and offering an alternative, it is important to understand the roots of the current situation. Japan’s massive plutonium stockpile is the result of five decades of technological and policy failure. In 1966, Japan started producing nuclear energy commercially and, at its peak, the country had nearly 60 traditional light-water reactors (LWRs), using non-weapons-usable uranium fuel to supply the country with 34 percent of its energy.3 Regrettably, based on ill-founded fears of global uranium shortages, Japan also followed the trend of the 1960s by planning to construct and operate fast-neutron breeder reactors (FBRs), aiming to increase the energy value of uranium by converting more of it to plutonium for use as reactor fuel.

The government encouraged the reprocessing of Japan’s spent LWR fuel at home and abroad to separate plutonium to fuel FBRs, which the government expected to produce energy commercially as early as 1985.4 From 1974 to 2011, Japan spent $17 billion on developing FBRs,5 but the efforts failed. In December 1995, a sodium leak and fire at the prototype Monju FBR caused it to go offline until 2010,6 and in 2016 the government declared that it would decommission the facility.7

While the ill-fated breeder reactor was under development, the Japanese government also decided to mix some of its separated plutonium with uranium to make MOX fuel as a partial substitute for low-enriched uranium (LEU) fuel in its LWRs.8 In 1986, it first tested a small amount of such MOX fuel in its Tsuruga-1 reactor, laying the groundwork for commercialization.9 In 1988 testimony to the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Milton Hoenig of the Washington-based Nuclear Control Institute outlined Japan’s plans to deploy MOX fuel commercially in LWRs beginning in 1997. He testified that Japan planned to use 96 metric tons of plutonium in 12 LWRs from 1997 to 2017.10 In February 1997, Japan’s Federation of Electric Companies issued an even more ambitious plan to use MOX fuel in 16 to 18 LWRs from 1999 to 2010.11

While the ill-fated breeder reactor was under development, the Japanese government also decided to mix some of its separated plutonium with uranium to make MOX fuel as a partial substitute for low-enriched uranium (LEU) fuel in its LWRs.8 In 1986, it first tested a small amount of such MOX fuel in its Tsuruga-1 reactor, laying the groundwork for commercialization.9 In 1988 testimony to the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Milton Hoenig of the Washington-based Nuclear Control Institute outlined Japan’s plans to deploy MOX fuel commercially in LWRs beginning in 1997. He testified that Japan planned to use 96 metric tons of plutonium in 12 LWRs from 1997 to 2017.10 In February 1997, Japan’s Federation of Electric Companies issued an even more ambitious plan to use MOX fuel in 16 to 18 LWRs from 1999 to 2010.11

Japan did not come anywhere close to meeting its intended 1997 start date for deployment of MOX fuel in LWRs. Indeed, it missed by more than a decade. The multiple reasons for that delay help illustrate the foolhardiness of the JAEC’s new plan to expand MOX fuel use.

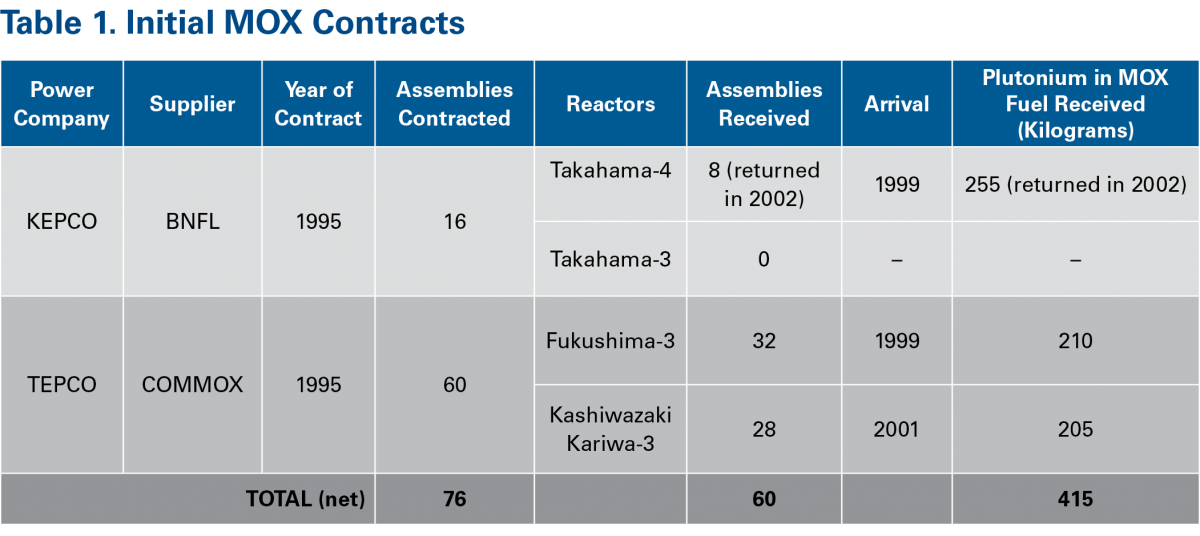

In the early 1990s, Japanese utilities signed contracts for MOX fuel supply from companies in the United Kingdom, France, and Belgium. Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO) and Kansai Electric Power Co. (KEPCO) were slated to be first to utilize MOX fuel.12 France’s Cogema, later renamed AREVA and then Orano, reprocessed TEPCO’s spent fuel, and the separated plutonium was used to fabricate MOX fuel in Belgium. Thirty-two MOX fuel assemblies for Fukushima Daichii-3, containing 210 kilograms of plutonium, were shipped to Japan in 1999, under a contract with a Franco-Belgian consortium known as COMMOX.13

KEPCO’s spent fuel was reprocessed by British Nuclear Fuel Ltd. (BNFL), which also contracted to fabricate MOX fuel for the Takahama-3 and -4 reactors.14 In 1999 the first batch from BNFL comprised eight MOX fuel assemblies containing 255 kilograms of plutonium.15 The MOX fuel assemblies from the UK and Belgium were shipped together to Japan from July to September 1999 (table 1).16

In October 1999, the Japanese utilities were on the verge of loading MOX fuel into the Fukushima Daiichi-3 and Takahama-4 reactors,17 but reports emerged that BNFL had falsified quality-control data of the MOX fuel for the KEPCO reactors. Takahama-4 was intended to be the first reactor to use MOX fuel after receiving its eight assemblies in October 1999. Two months prior, BNFL discovered and then disclosed that its employees had falsified data for other MOX fuel still in the UK but intended for the sister reactor, Takahama-3. This raised concerns that the data for the Takahama-4 fuel, just arriving in Japan, also had been falsified.

KEPCO reported in September 1999 that, on the basis of its own analysis, the Takahama-4 fuel was safe.18 Yet, two anti-nuclear Japanese nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), Green Action and Mihama-no-Kai, already had persuaded Japanese officials to obtain and provide them the BNFL data to conduct an independent analysis.19

Apparently trying to hinder such external oversight, BNFL did not release computer files but only paper books of data on the pellet size. Undeterred, the two NGOs copied and distributed the paper data sets for local citizens to assist in reviewing and then produced an analysis showing that BNFL had falsified the quality control, which UK regulatory authorities confirmed in November 1999.20 It turned out that BNFL employees had not manually measured the size of pellets, as required, but simply copied and pasted the measurements from earlier batches.

Following these disclosures, the start dates for use of MOX fuel in the Takahama-3 and -4 reactors were postponed. Unirradiated MOX fuel assemblies containing 255 kilograms of plutonium were returned to the UK in 2002, and BNFL paid $100 million compensation to KEPCO.21

After the initial delay in MOX fuel use at Takahama, Japanese citizens filed a lawsuit to stop the deployment of MOX fuel at Fukushima Daichii-3. Anti-nuclear activists presented evidence to the district court that production standards in Belgium were even lower than those at BNFL.22 The activists ultimately lost the case, but the governor of Fukushima retracted previously granted permission to deploy MOX fuel in the reactor, due to a combination of the BNFL scandal and the revelation in 2001 that TEPCO had falsified inspection data to hide the presence of cracks in some reactors.23 MOX fuel assemblies that had been shipped to the Fukushima Daichii-3 reactor were placed in storage.24

The third power plant slated for MOX fuel was Kashiwazaki Kariwa. Some surrounding communities had unsuccessfully opposed building the reactors, but the receipt of MOX fuel assemblies from France in 2001 magnified public opposition. Anti-nuclear NGOs persuaded the local legislature to hold a referendum and launched a comprehensive education campaign, including distributing informational leaflets. In the May 2001 referendum, 54 percent of voters in the village of Kariwa opposed the deployment of MOX fuel, with voter turnout of 88 percent.25

Despite this vote, the mayor of Kariwa was on the verge of approving MOX fuel use in 2002, but it was revealed that TEPCO had concealed its periodic inspections data. In September 2002, the prefecture formally withdrew its approval for MOX fuel use. As of July 2018, the fresh MOX fuel assemblies still had not been inserted into the reactor, 17 years after they were delivered.26 This poses a security risk because the unirradiated MOX fuel contains over 200 kilograms of plutonium, sufficient for at least 20 nuclear weapons.

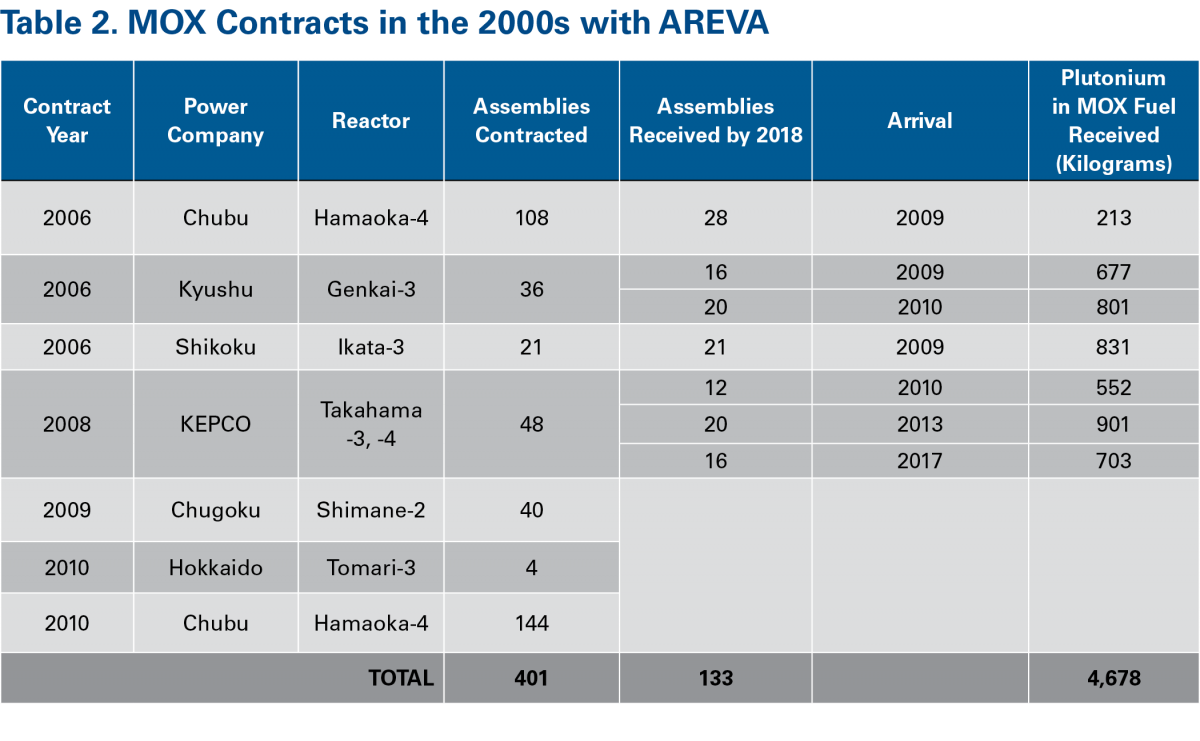

Renewed Japanese support for MOX fuel emerged in 2007, when three Japanese utilities signed contracts with AREVA, which started producing the fuel to be delivered between 2007 and 2020.27 Six Japanese utilities eventually signed MOX fuel contracts between 2006 and 2010 (table 2). Although 401 assemblies were contracted to be fabricated by AREVA, only 133 had been received by Japanese utilities as of 2018.

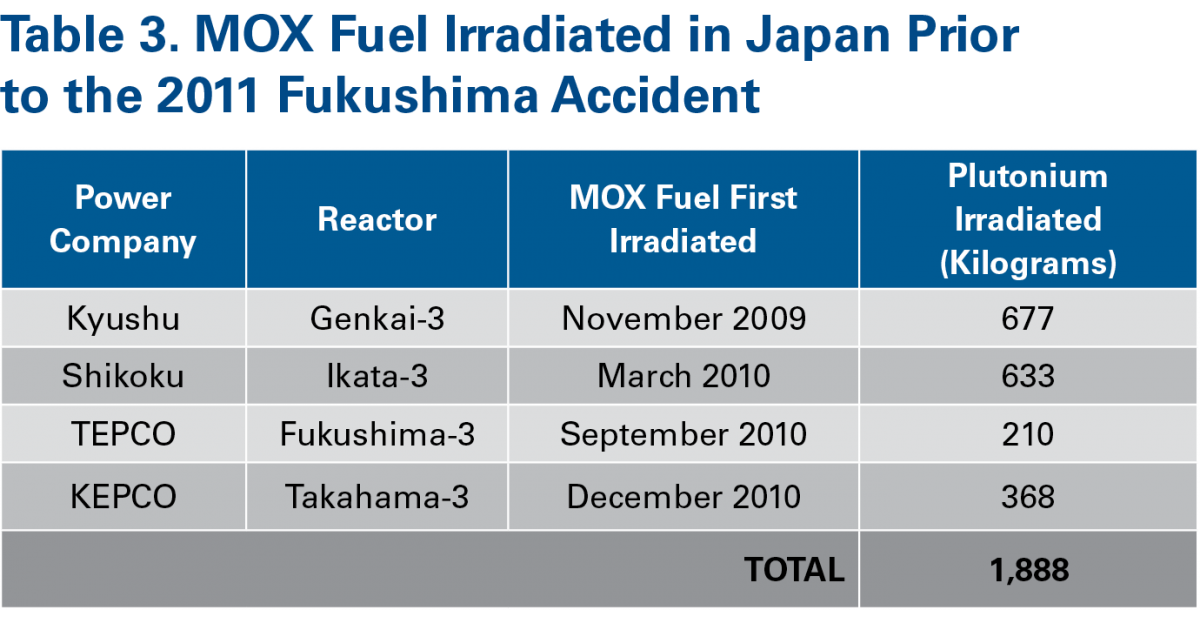

Finally, Japan commercially irradiated its first MOX fuel in an LWR in 2009, some 12 years behind the original schedule, only to be stopped two years later after use in only four reactors by the 2011 Fukushima accident (table 3). Since 2016, Japan has restarted MOX fuel usage, but failed to expand it. As of July 2018, Japan’s net imports of MOX fuel had contained 5.1 metric tons of plutonium (tables 1 and 2), and Japan was still storing unirradiated MOX fuel containing 1.7 metric tons of plutonium.28 Thus, in the history of its commercial LWR program, Japan has irradiated MOX fuel containing only about 3.4 metric tons of plutonium, a tiny fraction of its remaining plutonium stockpile.29

The Fukushima disaster, in March 2011, triggered an orderly shutdown of all nuclear power reactors in Japan by May 2012, during scheduled maintenance. Restarting these plants requires approval under the stricter regulations of a new Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA), which is tantamount to relicensing and has been partial and gradual. In July 2018, only eight of Japan’s historical total of 59 reactors, including two still under construction, were operating, of which three had some MOX fuel in their cores.30

The Fukushima disaster, in March 2011, triggered an orderly shutdown of all nuclear power reactors in Japan by May 2012, during scheduled maintenance. Restarting these plants requires approval under the stricter regulations of a new Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA), which is tantamount to relicensing and has been partial and gradual. In July 2018, only eight of Japan’s historical total of 59 reactors, including two still under construction, were operating, of which three had some MOX fuel in their cores.30

Japan’s pilot-scale reprocessing plant is being decommissioned, but the Japanese government still anticipates the start of commercial operations at the Rokkasho reprocessing plant in 2021, producing up to an additional eight metric tons of plutonium annually.31 This plan continues on apparent autopilot despite Japan having terminated the FBR program, which was the original rationale for reprocessing, and the country currently operating only a fraction of its LWRs in the wake of the Fukushima disaster.

The consequence of reprocessing spent fuel for four decades, while failing repeatedly to implement large-scale use of MOX fuel, is that Japan has accumulated more than 47 metric tons of unirradiated plutonium. That is more plutonium than in the nuclear weapons programs of the UK, France, China, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea—combined.

The plutonium is reactor-grade but fully capable of producing reliable nuclear weapons.32 At the start of 2018, Japan possessed 10.5 metric tons of plutonium domestically, while also owning 15.5 metric tons in France and 21.2 metric tons in the UK. Since then, Japan has inserted and irradiated additional MOX fuel in the Genkai-3 reactor, reducing its domestic stock of unirradiated plutonium by 640 kilograms to less than 10 metric tons, but its stockpile in the UK will soon grow by an equivalent amount.33

Flawed Plan

On July 31, 2018, the JAEC issued its revised guidelines titled “Basic Principles on Japan’s Utilization of Plutonium.”34 This document initially declares, promisingly, that “Japan will reduce the size of its plutonium stockpile,” but the strategy is actually based on boosting plutonium commerce by “promoting collaboration and cooperation among the operators” of Japan’s nuclear power plants to increase their use of MOX fuel. Further revealing the intention to expand the plutonium economy, the JAEC reports that “Japan Nuclear Fuel Limited (JNFL) plans to complete the construction of the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant and the MOX Fuel Fabrication Plant in the first half” of fiscal years 2021 and 2022, respectively.

This policy, ostensibly intended to reduce Japan’s plutonium stockpile by increasing domestic use of MOX fuel, has four major problems. First, Japan cannot quickly accelerate use of MOX fuel because it lacks the reactors to do so. Only nine Japanese reactors are licensed to use MOX fuel. Of those, two (Onagawa-3 and Kashiwazaki Kariwa-3) have not applied to restart in the wake of the 2011 earthquake-driven Fukushima disaster. The potential restart of two others (Tomari-3 and Shimane-2) is hindered by related earthquake concerns. In Shizuoka, the governor and mayors oppose the restart of another reactor (Hamaoka-4). Operation of a sixth reactor (Ikata-3) was suspended in December 2017 by court injunction. That leaves only three reactors that currently can operate with MOX fuel: Takahama-3 and -4 and Genkai-3. Together they annually can irradiate only 1.5 metric tons of plutonium, or barely 3 percent of Japan’s stockpile, a rate much too slow to address international concerns.

Second, even if Japan could increase the use of MOX fuel by licensing other reactors to use it, that would be counterproductive. Increased domestic use of MOX fuel would spur calls from Japan’s nuclear industry to finalize the domestic reprocessing plant and finish construction of the adjoining MOX fuel fabrication facility, which is only 12 percent complete because work was suspended after the Fukushima accident. The JAEC plan says the MOX fuel industry should “minimize the feedstock” of plutonium, but Japanese officials insist they will need a five-year working stock, which is potentially up to 40 metric tons of plutonium, in light of the new reprocessing plant’s capacity of eight metric tons annually. This obviously would not solve the plutonium-stockpile problem but rather perpetuate and magnify it in Japan. For perspective, the working stock of France’s MOX fuel industry is 35 metric tons of plutonium, but Japanese officials say that Japan’s more diverse reactors would require a greater variety of MOX fuel and thus extra working stock.

Third, there are quicker and safer ways for Japan to reduce its plutonium stockpile. About 21 (soon to be 22) metric tons of Japan’s plutonium, nearly half the stockpile, is in the UK, which has offered to take ownership for the right price. Other countries already have accepted this UK offer, including Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden.35 Japan should do likewise, quickly paying the UK to take title to all of its plutonium there, which overnight would cut Japan’s stockpile by 45 percent, much faster than the 3 percent annual reduction through MOX fuel use.

Japanese utilities also could save money by doing so because they would avoid the expense of storing the plutonium in the UK and eventually fabricating it into MOX fuel, which costs nine times more than LEU fuel.36 Japan’s government could even subsidize the title transfer by using its reprocessing fund, which holds payments by utilities to manage nuclear waste.

Fourth, most of Japan’s 10 metric tons of domestic unirradiated plutonium cannot currently be used in its reactors. More than six metric tons are in the form of separated plutonium, which Japan has no commercial facility to fabricate into MOX fuel. Another nearly two metric tons was fully or partially fabricated into a different type of fuel for the now-terminated FBRs, which cannot be inserted into LWRs. That means only 1.7 metric tons of the unirradiated plutonium in Japan, contained in imported MOX fuel, is readily usable in reactors, and some of it only if more reactors are restarted.

For the other eight metric tons held domestically, Japan could develop technology to dispose of it as waste in coordination with the United States, which last May announced its own plan to dispose of 34 metric tons of weapons plutonium as waste. To the JAEC’s credit, its plan calls for examining the “disposal of plutonium that is associated with research and development purposes.” Tokyo and Washington already have a mechanism for such technical cooperation, known as the U.S.-Japan Plutonium Management Experts Group, which should be revitalized to expedite such disposal.

Recommendations

Japan needs a different plan than boosting use of MOX fuel to attain its stated national goal of reducing its plutonium stockpile. To start, Japan should pay the UK to take ownership of the 22 metric tons there. Next, Tokyo should work with Washington on technology to quickly dispose as waste the eight metric tons of plutonium in Japan that cannot readily be used as fuel. That leaves about 15.5 metric tons of plutonium in France and two metric tons in Japan, a more manageable quantity that could be dealt with relatively quickly as a combination of waste and MOX fuel.

In this way, Japan could eliminate its plutonium stockpile in perhaps five years, assuming that it also terminated its costly, unnecessary, dangerous, and incomplete facilities for reprocessing spent fuel and fabricating MOX fuel. Going forward, Japan should switch to direct disposal of spent fuel, as all other countries, except France, that previously used MOX fuel in multiple thermal reactors already have done. Indeed, the JAEC’s most useful recommendation is to “[s]teadily promote efforts toward expanding storage capacity for spent fuel.”

Assuming Japan does not secretly wish to preserve a nuclear weapons option, this proposed road map could reduce its plutonium stockpile rapidly. If Japan instead expands use of MOX fuel as the JAEC recommends, thereby increasing its domestic stockpile of plutonium, neighboring countries will question Japan’s intentions and respond accordingly. That could ignite a latent or, even worse, actual nuclear arms race in East Asia. The Japanese government should think twice to make sure that its energy policy does not undermine its security policy.

ENDNOTES

1. Nuclear Proliferation Prevention Project, “Plutonium for Energy?” n.d., http://sites.utexas.edu/prp-mox-2018/.

2. Yukio Tajima, “Japan’s ‘plutonium exception’ under fire as nuclear pact extended; Beijing and Seoul question why US allows only Tokyo to reprocess,” NIKKEI Asian Review, July 14, 2018

3. Japan Atomic Energy Commission (JAEC), “Plutonium Utilization in Japan,” October 2017, p. 1, http://www.aec.go.jp/jicst/NC/iinkai/teirei/siryo2017/siryo38/siryo3-1.pdf; Susan E. Pickett, “Japan’s Nuclear Energy Policy: From Firm Commitment to Difficult Dilemma Addressing Growing Stocks of Plutonium, Program Delays, Domestic Opposition, and International Pressure,” Energy Policy, Vol. 30, No. 15 (December 2002): 1337–1355.

4. Pickett, “Japan’s Nuclear Energy Policy,” p. 1341.

5. International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM), “Plutonium Separation in Nuclear Power Programs: Status, Problems, and Prospects of Civilian Reprocessing Around the World,” July 2015, p. 62, http://fissilematerials.org/library/rr14.pdf.

6. “Opposition to Dangerous MOX Fuel,” Nuke Info Tokyo, No. 127 (November/December 2008), pp. 1-2, http://www.cnic.jp/english/newsletter/pdffiles/nit127.pdf.

7. “Japanese Government Says Monju Will Be Scrapped,” World Nuclear News, December 22, 2016, http://www.world-nuclear-news.org/NP-Japanese-government-says-Monju-will-be-scrapped-2212164.html.

8. Kenichiro Kaneda, “Plutonium Utilization Experience in Japan,” in Mixed Oxide Fuel (MOX) Exploitation and Destruction in Power Reactors, ed. E.R. Merz et al. (Dordrecht: Springer, 1995), p. 163.

9. JAEC, “Plutonium Utilization in Japan,” p. 3.

10. Milton Hoenig, “Production and Planned Use of Plutonium in Japan’s Nuclear Power Reactors During 30-Year Base Period of the Proposed U.S.-Japan Agreement” (statement before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs hearing on the United States-Japan Nuclear Cooperation Agreement, March 2, 1988).

11. “Opposition to Dangerous MOX Fuel.” In 2005 the deadline for expanding mixed-oxide (MOX) fuel to this many reactors was pushed back five years to 2015.

12. Jinzaburo Takagi et al., “Comprehensive Social Impact Assessment of MOX Use in Light Water Reactors,” Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center (CNIC), November 1997, p. 252, http://www.cnic.jp/english/publications/pdffiles/ima_fin_e.pdf.

13. Mayumi Negishi, “High Waves Hamper MOX Fuel Delivery,” Japan Times, September 22, 1999; IPFM, “Mixed Oxide (MOX) Fuel Imports/Use/Storage in Japan,” April 2015, http://fissilematerials.org/blog/MOXtransportSummary10June2014.pdf.

14. “Opposition to Dangerous MOX Fuel.”

15. IPFM, “Mixed-Oxide (MOX) Fuel Imports/Use/Storage in Japan.”

16. Cumbrians Opposed to a Radioactive Environment, “MOX Transport,” n.d., http://corecumbria.co.uk/mox-transport/ (accessed September 18, 2018).

17. Edwin S. Lyman, “The Impact of the Use of Mixed-Oxide Fuel on the Potential for Severe Nuclear Plant Accidents in Japan,” Nuclear Control Institute, October 1999, http://www.nci.org/j/japanmox.htm.

18. “The MOX Fuel Conundrum,” Japan Times, July 26, 2013.

19. Aileen Mioko Smith, interview with with Hina Acharya, Kyoto, Japan, January 6, 2018.

20. “Japan: MOX Program to Restart at Takahama,” Nuclear Monitor, No. 607 (April 2004), https://wiseinternational.org/nuclear-monitor/607/japan-mox-program-restart-

takahama.

21. “BNFL Execs Bid to Drum Up Trust and New Deals,” Japan Times, September 20, 2000.

22. “Another MOX Scandal?” Nuclear Monitor, No. 542 (January 2001), https://www.wiseinternational.org/nuclear-monitor/542/another-mox-scandal.

23. “Tepco Not to Be Punished in Reactor Crack Scandal,” Japan Times, September 15, 2001.

24. CNIC, “Japanese Nuclear Power Companies’ Pluthermal Plans,” March 2007, http://www.cnic.jp/english/topics/cycle/MOX/pluthermplans.html.

25. David Cyranoski, “Referendum Stalls Japanese Nuclear Power Strategy,” Nature, No. 411 (June 14, 2001), p. 729; “Niigata Village Says No to MOX Fuel Use at Nuke Plant,” Japan Times, May 28, 2001. “刈羽村住民投票でプルサーマル反対が多数,” May 28, 2001, http://www.kisnet.or.jp/nippo/nippo-2001-05-28-1.html.

26. “MOX Fuel Unloaded in Niigata; Security Tight as British Ship Docks at Tepco Nuclear Plant,” Kyodo, March 25, 2001.

27. Areva, “Reference Document 2006,” April 27, 2007, http://www.sa.areva.com/mediatheque/liblocal/docs/groupe/Document-reference/2006/pdf-doc-ref-06-va.pdf.

28. Japanese Office of Atomic Energy Policy, “The Status Report of Plutonium Management in Japan - 2017,” July 31, 2018, http://www.aec.go.jp/jicst/NC/about/kettei/180731_e.pdf.

29. This excludes the small amount of plutonium in experimental MOX-fuel assemblies inserted in two reactors in the 1980s.

30. “Compliance with New Nuclear Power Plant Regulatory Standards,” Kakujoho, http://kakujoho.net/npt/aec_pu2.html#moxstts; Masafumi Takubo, email to author, July 3, 2018. See Japan Nuclear Safety Institute, Licensing Status for the Japanese Nuclear Facilities,” August 10, 2018, http://www.genanshin.jp/english/facility/map/.

31. “Decommissioning Plan for Tokai Approved,” World Nuclear News, June 13, 2018, http://www.world-nuclear-news.org/WR-Decommissioning-plan-for-Tokai-approved-1306184.html; Masafumi Takubo, “Closing Japan’s Monju Fast Breeder Reactor: The Possible Implications,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 73, No. 3 (May 2017): 183.

32. Gregory S. Jones, Reactor-Grade Plutonium and Nuclear Weapons: Exploding the Myths (Arlington, VA: Nonproliferation Policy Education Center, 2018).

33. Japanese Office of Atomic Energy Policy, “The Status Report of Plutonium Management in Japan - 2017.” Japan’s plutonium in the UK will rise by another 0.6 metric tons by 2019, after proper crediting of additional plutonium separated from Japanese spent fuel by reprocessing in the United Kingdom.

34. JAEC, “The Basic Principles on Japan’s Utilization of Plutonium,” July 31, 2018, http://www.aec.go.jp/jicst/NC/iinkai/teirei/3-3set.pdf.

35. UK Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC), “Plutonium Deal Brings Security Benefits,” July 3, 2014, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/plutonium-deal-brings-security-benefits--2; DECC, “Statement by Michael Fallon: Management of Overseas Owned Plutonium in the UK,” April 23, 2013, https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/management-of-overseas-owned-plutonium-in-the-uk; UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, “Management of Overseas Owned Plutonium in the UK,” HLWS425, January 19, 2017, https://www.parliament.uk/business/publications/written-questions-answers-statements/written-statement/Lords/2017-01-19/HLWS425/.

36. “MOX imports have cost at least ¥99.4 billion, much higher than uranium fuel,” Energy Monitor Worldwide, February 23, 2015.

Alan J. Kuperman is an associate professor at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is coordinator of the Nuclear Proliferation Prevention Project (NPPP). Hina Acharya is a 2018 graduate of the school’s Master of Global Policy Studies program. This article draws on her chapter, “MOX in Japan: Ambitious Plans Derailed,” in the NPPP’s recent book Plutonium for Energy? Explaining the Global Decline of MOX. Research for this article was supported by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Japan operates a ballistic missile defense system, with Aegis-equipped warships providing the first line of defense against an incoming missile during its midcourse trajectory. Japan’s second line of defense is its Patriot Advanced Capability-3 (PAC-3) mobile systems that can be deployed to protect high-value targets, such as military bases and cities, using hit-to-kill interceptors during the terminal phase of an incoming missile’s flight path.

Japan operates a ballistic missile defense system, with Aegis-equipped warships providing the first line of defense against an incoming missile during its midcourse trajectory. Japan’s second line of defense is its Patriot Advanced Capability-3 (PAC-3) mobile systems that can be deployed to protect high-value targets, such as military bases and cities, using hit-to-kill interceptors during the terminal phase of an incoming missile’s flight path.

The defense budget for fiscal year 2018, approved at the end of March by the Japanese bicameral legislature, the Diet, included funds to introduce cruise missiles to the country’s overall military capabilities. Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera first officially announced Japan’s intentions to purchase the missiles in December 2017, saying that they would be used exclusively for defense purposes as “stand-off missiles that can be fired beyond the range of enemy threats.”

The defense budget for fiscal year 2018, approved at the end of March by the Japanese bicameral legislature, the Diet, included funds to introduce cruise missiles to the country’s overall military capabilities. Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera first officially announced Japan’s intentions to purchase the missiles in December 2017, saying that they would be used exclusively for defense purposes as “stand-off missiles that can be fired beyond the range of enemy threats.” The deal marks the first agreement between Japan and a state that has not ratified the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). Although not an NPT member, India received a waiver from the Nuclear Suppliers Group in 2008 allowing it to conduct nuclear commerce for peaceful purposes.

The deal marks the first agreement between Japan and a state that has not ratified the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). Although not an NPT member, India received a waiver from the Nuclear Suppliers Group in 2008 allowing it to conduct nuclear commerce for peaceful purposes.  For decades, citizen diplomats, scientists, physicians, students, and concerned people the world over have successfully pushed their leaders to achieve nuclear disarmament.

For decades, citizen diplomats, scientists, physicians, students, and concerned people the world over have successfully pushed their leaders to achieve nuclear disarmament. The deal will help New Delhi realize its ambitious plans to expand its civilian nuclear power program. According to the World Nuclear Association, India currently has 21 operating nuclear power reactors, six units under construction, and plans for more than 20 additional reactors.

The deal will help New Delhi realize its ambitious plans to expand its civilian nuclear power program. According to the World Nuclear Association, India currently has 21 operating nuclear power reactors, six units under construction, and plans for more than 20 additional reactors.