Volume 12, Issue 1, February 5, 2020

With the collapse of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty on August 2, the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) is now the only remaining arms control agreement limiting at least a portion of the U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals.

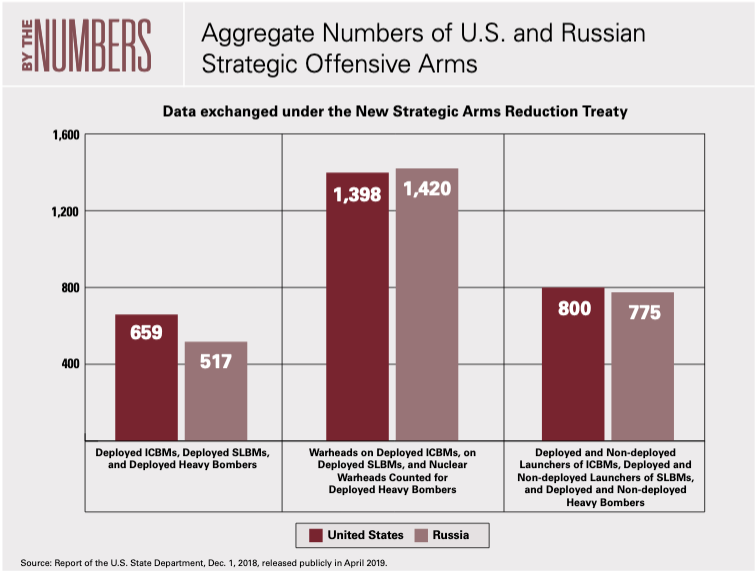

Signed in 2010, New START verifiably caps U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear arsenals at 1,550 deployed warheads, 700 deployed missiles and heavy bombers, and 800 deployed and nondeployed missile launchers and bombers. The treaty is slated to expire one year from today on February 5, 2021, but it can be extended by up to five years by agreement of the U.S. and Russian presidents.

Although Russia has indicated its support for a clean, unconditional extension, the Trump administration remains officially undecided about whether to extend the treaty and is seeking a more comprehensive arms control agreement that includes more types of Russian weapons as well as China.

If New START lapses without an extension or replacement, there will be no legally binding constraints on the world's two largest nuclear arsenals for the first time in half a century. The risk of unconstrained U.S.-Russian nuclear competition, and of even more strained bilateral relations, would grow.

Below are responses to some of the most common objections raised against New START. The criticisms range from understandable, to misleading, to disingenuous. None of them merit a decision to allow the treaty to lapse.

Claim: New START doesn’t include the new strategic nuclear delivery systems that Russian President Vladimir Putin unveiled in March 2018.

Response: In a March 2018 speech, Putin said that Russia is developing several new strategic nuclear weapons delivery systems designed to ensure that Russia can maintain an adequate nuclear deterrent in the face of unconstrained U.S. missile defenses. These systems include a new heavy ICBM (the Sarmat), hypersonic glide vehicle (the Avangard), nuclear-powered cruise missile (Skyfall), and nuclear-powered underwater torpedo (Poseidon).

U.S. Ambassador to Russia John Sullivan told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Oct. 30 that “if we were simply to extend New START now, without touching those other systems, which the Russians have been invested in, we’re tying our hands in not limiting what...the Russians see where their growth [is]…in their strategic assets.” Given the range of the new Russian weapons, it is reasonable to ask why they shouldn’t be limited by New START.

But Russia’s development of the weapons actually strengthens the case for extending New START. Russia has stated that the two systems closest to deployment (the Avangard, which began combat duty in late December, and Sarmat) would be captured by the treaty. Russia will be limited in how many of these weapons they can deploy, and the treaty’s verification regime will give the United States a clearer picture of how many of these weapons there are and where they are located. Russia last November exhibited the Avangard to U.S. inspectors per the terms of the agreement.

As for the other two weapons—Skyfall, a recent test of which resulted in a deadly explosion, and Poseidon—they are still in development and unlikely to be deployed in large numbers or before the mid-2020s at the earliest, according to independent open source and intelligence assessments. This means that these systems likely wouldn’t be fielded until after the expiration of an extended New START, which should make them less relevant in the administration’s current analysis of whether to extend the treaty.

(Putin also unveiled an air-launched ballistic missile, the Kinzhal, in his 2018 address. The missile reportedly began trial deployment in December 2017. Russia is currently planning to field the weapon on the shorter-range MiG-31 aircraft, in which case Kinzhal would not be accountable under New START.)

Moscow says that it is open to discussing limitations on the Skyfall, Poseidon, and Kinzhal in the format of strategic stability talks, but that capturing them would require an amendment to New START or a new agreement, in which case Moscow would have its own list of U.S. capabilities that should be addressed. Article V of the treaty states: “When a Party believes that a new kind of strategic offensive arm is emerging,” the two sides can discuss how to take the systems into account. Both sides are discussing the new systems, making use of this provision.

Extending New START provides the best and only chance to limit Russia's new strategic weapons. It would be illogical and irresponsible for the United States to forego another five years of limits on Russia's enormous arsenal of hundreds of existing strategic nuclear weapons because Russia might deploy some new weapons not covered by the treaty over five years from now.

Claim: New START doesn’t include Russia’s large arsenal of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

Response: Russia maintains a large arsenal of approximately 2,000 non-strategic nuclear warheads for short-range delivery. The United States is estimated to possess about 200 such weapons, approximately 180 of which are housed on the territory of five European NATO member states. David Trachtenberg, who served as Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy from October 2017 to July 2019, wrote last November that New START “ignores the significant and growing Russian advantage in non-strategic nuclear forces.”

Contrary to popular belief, Russia’s arsenal of non-strategic nuclear warheads, which are believed to be housed in central storage, has actually decreased significantly since New START was negotiated.

Talks on limiting both countries’ non-strategic nuclear weapons are nonetheless long overdue. The Senate during its review of New START in 2010 called for future negotiations with Russia to address the imbalance between the two sides in non-strategic nuclear weapons.

But New START was designed to focus on limiting Russian strategic nuclear weapons that can directly threaten the U.S. homeland. Talks to limit non-strategic nuclear warheads would be time-consuming and difficult. Russia insists that a future agreement limiting a broader range of nuclear weapons also limit U.S. missile defenses and advanced conventional strike weapons and include British and French nuclear forces. Russia is also likely to demand that any agreement limiting Russian short-range nuclear weapons mandate the removal of the U.S. short-range weapons deployed in Europe and possibly conventional forces near Russia’s border. The Trump administration has given no indication that it is willing to address these Russian demands.

Extending New START would buy five additional years with which to engage in negotiations with Russia to attempt to capture weapons and technologies not limited by the treaty while retaining limits on Russia’s strategic nuclear forces. Ditching the treaty on the other hand would leave all types of Russian weapons unconstrained. Threatening Russia with New START’s expiration is not going to force the Kremlin to unilaterally concede to U.S. demands on non-strategic weapons.

Claim: New START doesn’t include China.

Response: The Trump administration argues that China must be included in the arms control process. “[I]t is vital that nuclear arms control adapt itself to the modern strategic environment; we are committed to involving both Russia and China…by negotiating a trilateral nuclear arms control agreement,” said Assistant Secretary of State for International Security and Nonproliferation Christopher Ford in a Dec. 13 speech in Brussels. “There can be no serious future for arms control that does not involve both Moscow and Beijing, and they know it,” Ford claimed.

Seeking to convince China, which has never formally participated in the arms control process, to get off the arms control sidelines is an important and worthwhile goal. But there is no realistic possibility of concluding an unprecedented trilateral deal with Russia and China before New START expires in 2021. Though Trump has repeatedly claimed that China is excited to begin trilateral talks, China has repeatedly made its opposition to such talks clear.

Currently, the United States and Russia each have a total of about 6,000 nuclear warheads, while China has about 300. If negotiations on a new agreement including China are to become a real possibility, either “the U.S. agrees to reduce its arsenal to China’s level or agrees for China to raise its arsenal to the U.S. level,” Fu Cong, director of the arms control department at the Chinese Foreign Ministry, said Nov. 8.

In addition, nearly a year after the Trump administration first called for including China in arms control talks, officials have yet to articulate their goals for a multilateral accord or strategy for achieving it. Nor does the administration appear to have the personnel to negotiate such a deal.

Jettisoning New START’s limits on Russia’s enormous existing arsenal of deployed strategic nuclear weapons—just because it doesn't cover all Russian weapons or include China's much smaller arsenal—would be akin to cutting off our nose to spite our face. As Pranay Vaddi, a fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, has written, “there is no chance for arms control with China if New START is permitted to expire. It is unimaginable that China would join the arms control process if the U.S. and Russia walked away.”

Fortunately, extending New START is perfectly compatible with seeking to engage China on arms control and is a necessary foundation from which to pursue more ambitious arms control talks. In the near-term, the United States should pursue a sustained strategic stability dialogue with Beijing focused strengthening crisis stability, reducing the risk of unintended escalation, and exploring what would be required to enhance transparency about China’s nuclear forces and cap the growth of those forces.

Claim: Holding out on extending New START provides leverage to bring Russia and China to the negotiating table on a broader arms control agreement.

Response: As the administration continues to weigh whether to extend New START, some officials argue that whatever the final decision, it would premature to extend now. Undersecretary of Defense for Policy John Rood told the Senate Armed Services Committee on Dec. 5 that “if the United States were to agree to extend the treaty now, I think it would make it less likely that we would have the ability to persuade Russia and China to enter negotiations on a broader agreement.”

The claim that holding out on extension provides the United States with leverage over Russia and China is unconvincing for several reasons.

First, New START is useless as a bargaining chip unless the administration is willing to walk away from the treaty if Russia and China don’t meet U.S. demands for talks. But making New START a chip in a high-stakes poker game with Russia and China is a dangerous gamble because the treaty is too important to be gambled away.

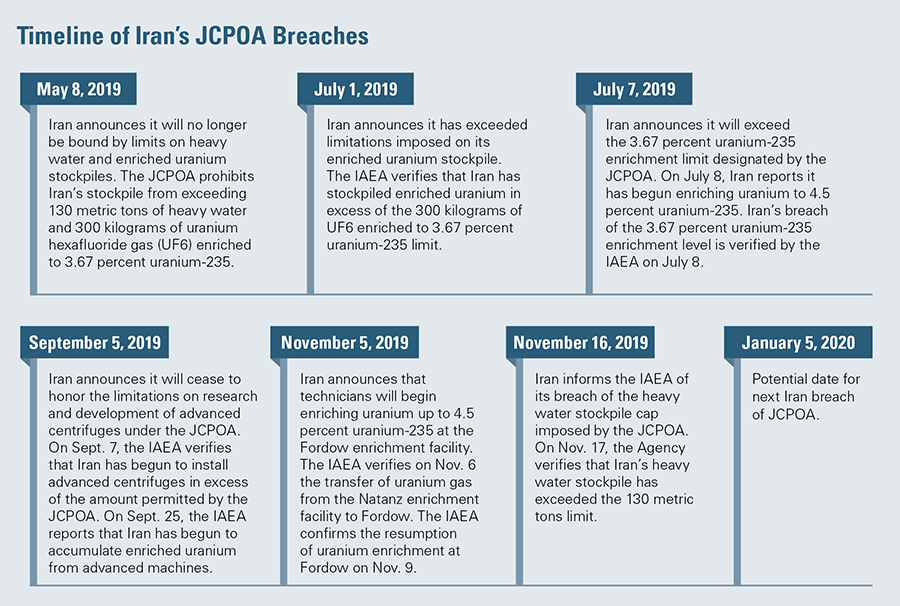

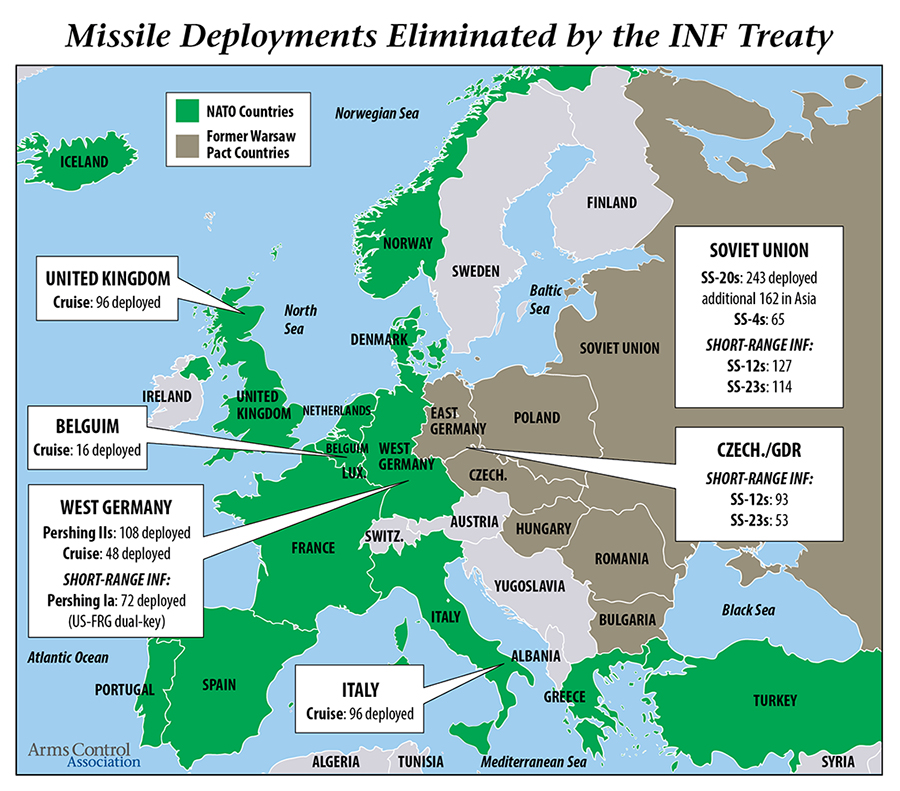

Second, the Trump administration does not have a good track record when it comes to attempting to leverage existing nuclear agreements into better deals. In the case of the Iran Deal, the administration’s threats to withdraw failed to convince Iran to agree to better terms. In the case of the INF Treaty, the administration’s threat to withdraw failed to convince Russia to return to compliance. President Trump ultimately withdrew from both agreements with no viable plan to replace them.

Third, as Vincent Manzo and Madison Estes wrote last July, the longer the administration waits to extend New START, “the more attention U.S. defense, intelligence, and diplomatic officials will likely devote to figuring out how to manage the challenges that would emerge without New START—and the less they will have to conceptualize and negotiate new and plausible arms control arrangements for the emerging strategic landscape.”

Fourth, Russia has provided no indication that it would trade an extension of New START for talks on limiting weapons not covered by the treaty. Russia has repeatedly made clear the U.S. concessions it is seeking in return for a new agreement capturing additional types of weapons. Moreover, Moscow is no doubt aware that most U.S. allies strongly support a clean extension and would likely blame Washington for the treaty’s collapses. While Moscow would prefer to extend New START, it also appears content with a world in which the treaty dies and the United States is left holding the bag.

Finally, there is no evidence that China supports New START so strongly that it would reverse its longstanding policy and join trilateral talks with the United States and Russia to avert the treaty’s collapse.

Claim: Russia is violating other arms control agreements.

Response: The Trump administration has stated that Russian noncompliance with other arms control agreements is one of the factors it is considering in weighing whether to extend New START. Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Joe Dunford said last September that “it’s difficult for me right now in the wake of the violation of the INF Treaty to say automatically that I support extending START.”

Despite its concerns with Russian noncompliance with other agreements, the United States continues to assess the Russia remains in compliance with New START. Attempting to “punish” Russia’s violations of other agreements by abandoning New START would senselessly and counterproductively free Russia to expand the number of strategic nuclear weapons pointed at the United States after New START expires in 2021. Moreover, letting New START expire won’t discourage Russia from future violations, especially since the United States is likely to be blamed for New START’s collapse.

Claim: The United States hasn’t sufficiently modernized its nuclear arsenal.

Response: Some opponents of extending New START argue that the treaty should be allowed to die because modernization of the U.S. nuclear arsenal is not proceeding swiftly enough. As Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman James Risch (R-Idaho) claimed last May, “We just haven't followed through on it [modernization] and it's—it's very unfortunate. One of the many reasons why I oppose…a gratuitous five-year extension, given where we are.”

New START was negotiated with U.S. nuclear modernization in mind and is consistent with the Pentagon and Energy Department’s planned recapitalization of U.S. nuclear forces and their supporting infrastructure.

In November 2010, when the Senate was debating New START, the Obama administration pledged to spend about $85 billion between fiscal years 2011 and 2020 on nuclear weapons activities at the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA). (Separately the Defense Department identified $100 billion in planned spending on delivery system sustainment and modernization, though it was never entirely clear what this number included).

Spending on NNSA weapons activities over the 10-year period between fiscal years 2011 and 2020 exceeded what was projected. The Obama administration initially kept pace with the pledged levels, then had to cut back due to the unwillingness of House Republican appropriators to fund the requested amounts and later the 2011 Budget Control Act, and then returned to the pledged levels in fiscal years 2016 and 2017. The Trump administration for its part has blown way above the levels projected in 2010, and press reports indicate that the FY 2021 budget request will continue that trend. Spending on nuclear weapons by the Defense Department has greatly exceeded $100 billion since fiscal year 2011.

The question then is not whether the U.S. arsenal is being upgraded (it is), but whether the administration’s nuclear weapons spending plans are necessary or sustainable. The answer is that they are not. In fact, the costs and risks of the Trump administration’s nuclear weapons spending plans are compounded by its hostility to arms control. As Senate Foreign Relations Committee ranking member Robert Menendez (D-N.J.) noted last September, “bipartisan support for nuclear modernization is tied to maintaining an arms control process that controls and seeks to reduce Russian nuclear forces…We’re not interested in writing blank checks for a nuclear arms race with Russia.”

Congress should support both extending New START and adjusting the administration’s modernization plans because doing so makes sense for U.S. security. —KINGSTON REIF, director for disarmament and threat reduction policy

With the collapse of the INF Treaty, the only remaining agreement regulating the world’s two largest nuclear stockpiles is

With the collapse of the INF Treaty, the only remaining agreement regulating the world’s two largest nuclear stockpiles is  Chemical Weapons Use in Syria

Chemical Weapons Use in Syria