January/February 2020

By Kingston Reif and Shannon Bugos

The United States has conducted a second test of a missile formerly banned by the defunct Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. The Dec. 12 launch was described as “a prototype, conventionally configured, ground-launched ballistic missile from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California,” according to a Defense Department statement. The missile flew for “more than 500 kilometers,” a range capability prohibited by the treaty before the United States formally withdrew from the INF Treaty on Aug 2. (See ACT, September 2019.)

The Pentagon has not disclosed the type of missile that was tested, but some experts have speculated that the test involved the Castor IVB rocket motor, which has been used in the past for military space launches and in target vehicles for the Missile Defense Agency. The joint government-industry team began work preparing for the test after the United States suspended its treaty obligations in February 2019 and “executed the launch within nine months of contract award when the process typically takes 24 months,” said a statement from Vandenberg Air Force Base.

The Pentagon has not disclosed the type of missile that was tested, but some experts have speculated that the test involved the Castor IVB rocket motor, which has been used in the past for military space launches and in target vehicles for the Missile Defense Agency. The joint government-industry team began work preparing for the test after the United States suspended its treaty obligations in February 2019 and “executed the launch within nine months of contract award when the process typically takes 24 months,” said a statement from Vandenberg Air Force Base.

The December test followed an Aug. 18 test of a ground-launched, intermediate-range cruise missile just two weeks after the treaty withdrawal. Neither test demonstrated an operational system that the Pentagon plans to field, but rather showed initial capabilities.

The 1987 INF Treaty led to the elimination of 2,692 U.S. and Soviet nuclear and conventional, ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles having ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers.

Defense Secretary Mark Esper said on Dec. 12 that “once we develop intermediate-range missiles, and if my commanders require them, then we will work closely and consult closely with our allies in Europe, Asia, and elsewhere with regard to any possible deployments.”

Pentagon officials said in March that the department would pursue the development of a mobile, ground-launched cruise missile that has a range of about 1,000 kilometers and a mobile, ground-launched ballistic missile with a range of 3,000 to 4,000 kilometers. (See ACT, April 2019.)

The Defense Department requested $96 million in its fiscal year 2020 budget to develop three types of intermediate-range missiles. (See ACT, May 2019.) The final fiscal year 2020 defense appropriations bill approved by Congress in December provides $40 million less than the request.

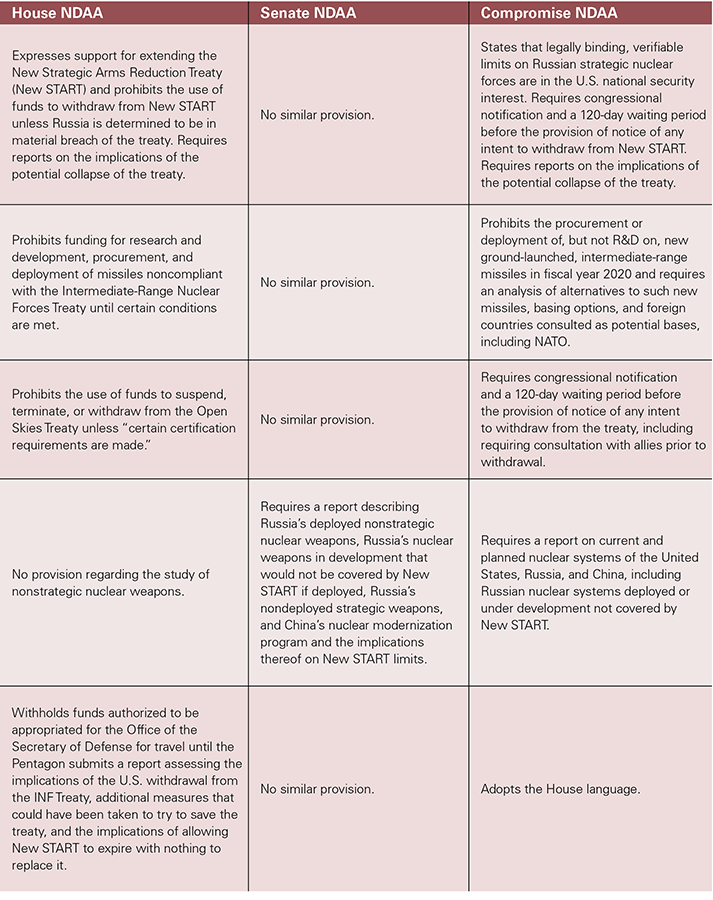

The final version of the fiscal year 2020 defense authorization bill, also approved by Congress in December, prohibits the use of current-year funds to procure and deploy missiles formerly banned by the INF Treaty, but does not prohibit their development and testing, as the House of Representatives' version of the bill had initially proposed. The bill also requires the Pentagon to report on the results of an analysis of alternatives that assesses the benefits and risks of such missiles, options for basing them in Europe or the Indo-Pacific region, and whether deploying such missile systems on the territory of a NATO ally would require a consensus decision by NATO.

Whether the Pentagon could base the missiles in Europe and East Asia remains to be seen. Despite their concerns about Russia and China, U.S. allies have not appeared eager to host them.

Russia and China reacted negatively to the ballistic missile test. Russia has “said more than once that the United States has been making preparations for violating the INF Treaty. This [missile test] clearly confirms that the treaty was ruined at the initiative of the United States,” according to Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov on Dec. 13.

Russia also claimed that the test vindicated its charge that the United States violated the INF Treaty in the past by using targets for missile defense tests with similar characteristics to treaty-prohibited missiles. Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov said on Dec. 26 that the test was “enabled by technology…which was earlier used to launch target missiles” and provided “direct proof of what we had been talking about for many years.”

A Chinese spokesperson said Dec. 13 the test “confirms…that the U.S. withdrawal is a premeditated decision. The real aim is to free itself to develop advanced missiles and seek unilateral military advantage.”

According to a Nov. 21 report in Defense News, Trump administration officials raised several concerns about the treaty at a meeting with NATO partners in Brussels and asked allies to provide their assessment of the benefits and risks of the treaty.

According to a Nov. 21 report in Defense News, Trump administration officials raised several concerns about the treaty at a meeting with NATO partners in Brussels and asked allies to provide their assessment of the benefits and risks of the treaty. Most notably, lawmakers approved the deployment beginning this fiscal year of a small number of low-yield nuclear warheads for submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) as proposed in the administration’s report of its Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), which was released in February 2018. (

Most notably, lawmakers approved the deployment beginning this fiscal year of a small number of low-yield nuclear warheads for submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) as proposed in the administration’s report of its Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), which was released in February 2018. (

The primary CEND working group held its second session in London on Nov. 20–22. (

The primary CEND working group held its second session in London on Nov. 20–22. ( Starting in 2018, China, North Korea, and Russia have held trilateral talks that have received less international attention than the stalled U.S.-North Korean diplomatic efforts to reach a settlement on denuclearization and peace on the Korean peninsula. The talks appear to have focused so far on converging the three countries’ positions to strengthen Pyongyang’s stance in negotiations with Washington. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said on Nov. 8 that the independent trilateral initiative should not be considered a substitute for the U.S.-North Korean dialogue, but the co-sponsored draft resolution purportedly calls for the “prompt resumption of the six-party talks or re-launch of multilateral consultations in any other similar format, with the goal of facilitating a peaceful and comprehensive solution through dialogue,” signaling Russia’s and China’s mounting interest in collaborating formally on North Korea’s denuclearization process.

Starting in 2018, China, North Korea, and Russia have held trilateral talks that have received less international attention than the stalled U.S.-North Korean diplomatic efforts to reach a settlement on denuclearization and peace on the Korean peninsula. The talks appear to have focused so far on converging the three countries’ positions to strengthen Pyongyang’s stance in negotiations with Washington. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said on Nov. 8 that the independent trilateral initiative should not be considered a substitute for the U.S.-North Korean dialogue, but the co-sponsored draft resolution purportedly calls for the “prompt resumption of the six-party talks or re-launch of multilateral consultations in any other similar format, with the goal of facilitating a peaceful and comprehensive solution through dialogue,” signaling Russia’s and China’s mounting interest in collaborating formally on North Korea’s denuclearization process. Conference participants adopted the Oslo Action Plan and the Oslo Declaration on a Mine-Free World, documents that reaffirmed their intent to achieve full treaty compliance, including mine destruction and clearance, “to the fullest extent possible” by 2025. Full compliance was a goal originally stated in the Maputo Action Plan, created at the 2014 review conference.

Conference participants adopted the Oslo Action Plan and the Oslo Declaration on a Mine-Free World, documents that reaffirmed their intent to achieve full treaty compliance, including mine destruction and clearance, “to the fullest extent possible” by 2025. Full compliance was a goal originally stated in the Maputo Action Plan, created at the 2014 review conference. “We did not accept the moratorium offered by Russia, but we considered that we should not just ignore it because it was open for discussion,” Macron said at a Nov. 28 press conference alongside NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg. It is in France’s interest, he said, to discuss such matters of security in a dialogue with Russia. NATO previously rejected Putin’s proposal in September, calling it not “credible.” (See

“We did not accept the moratorium offered by Russia, but we considered that we should not just ignore it because it was open for discussion,” Macron said at a Nov. 28 press conference alongside NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg. It is in France’s interest, he said, to discuss such matters of security in a dialogue with Russia. NATO previously rejected Putin’s proposal in September, calling it not “credible.” (See