The Trump administration’s first Congressional budget request pushes full steam ahead with the Obama administration’s excessive, all-of-the-above approach to upgrading the U.S. nuclear arsenal.

This continuity is not surprising given the Trump administration has begun a Nuclear Posture Review that is examining U.S. nuclear policy and strategy, including force structure and spending requirements. While it remains to be seen whether the administration will take the current upgrade plans in a new direction, its Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 budget proposal illustrates the risings costs of the nuclear mission and the threat it poses to other defense priorities.

The FY 2018 proposal contains significant increases for several Defense and Energy department nuclear weapons systems, including increases for some programs above what the Obama administration projected in its final FY 2017 budget submission. (See chart below.) The request does not make significant changes to the planned development timelines for these programs.

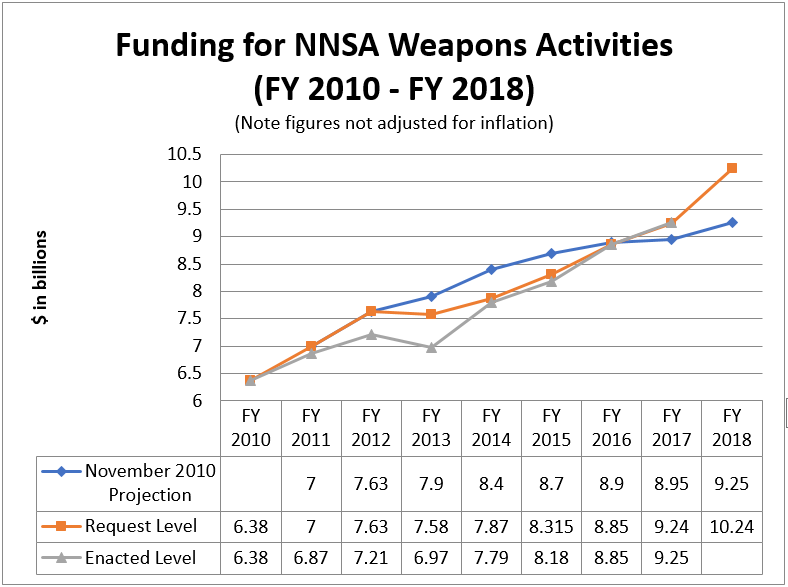

The largest increase in the budget request is for the Energy Department’s semiautonomous National Nuclear Security Administration’s (NNSA) nuclear weapons account. The proposal calls for $10.2 billion, an increase of roughly $1 billion above the FY 2017 appropriation and $570 million above the projection in Obama’s final budget request.

Despite the request for additional funding, none of the additional funds would be spent to accelerate warhead life extension programs or begin research and design on new warheads. Instead, the increase reflects cost growth in some programs, notably the refurbishment program for the B61 gravity bomb, and a commitment to address infrastructure issues.

The seeds for much of the increase were actually planted by former Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz. In a December 2015 letter to the White House, Moniz said that an additional $5.2 billion above the 5-year funding plan contained in the FY 2017 budget request would be needed to meet weapons program shortfalls.

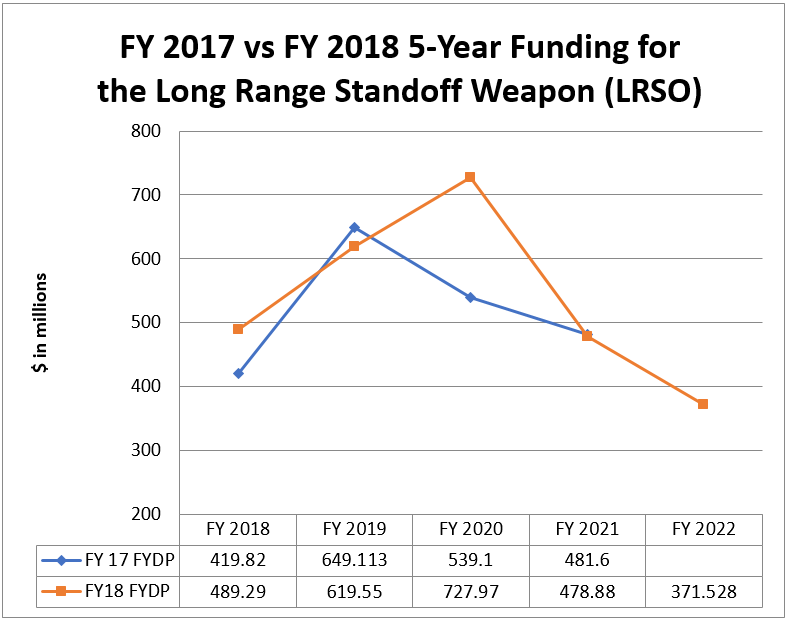

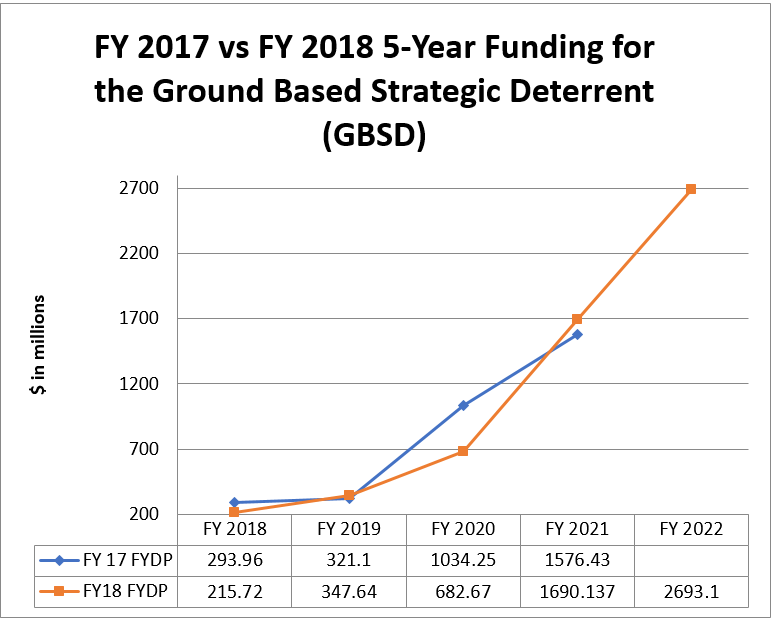

The Defense Department’s budget submission also includes larger than planned increases for the programs to build new fleets of nuclear air-launched cruise missiles and intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). Both of these programs saw their price tag rise during Pentagon reviews last summer. In the case of the new ICBM program, the cost could be double the Air Force’s initial 2015 projection of $62 billion.

If the Trump administration’s ongoing Nuclear Posture Review does not alter the current spending trajectory—or worse, accelerates or expands upon it—spending on nuclear weapons will pose a major threat to more relevant national security programs, to say nothing about Trump’s pledge to expand the non-nuclear military.

President Trump has declared his ambition to “greatly strengthen and expand” U.S. nuclear weapons capabilities, and has criticized the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) with Russia, suggesting he may be looking to change nuclear policy in significant ways.

A February 2017 Congressional Budget Office report estimates that the United States will spend $400 billion (in then-year dollars) on nuclear weapons between fiscal years 2017 and 2026. The new projection is an increase of $52 billion, or 15 percent, over the CBO’s most recent previous estimate of the 10-year cost of nuclear forces, which was published in January 2015 and put the total cost at $348 billion.

In fact, the CBO’s latest projection suggest that the cost of nuclear forces could greatly exceed $1 trillion over the next 30 years.

What makes the growing cost to sustain the nuclear mission so worrisome for military planners is that costs are scheduled to peak during the mid-2020s and overlap with large increases in projected spending on conventional weapon system modernization programs. Numerous Pentagon officials and outside experts have warned about the affordability problem posed by the current approach and that it cannot be sustained without significant and sustained increases to defense spending or cuts to other military priorities.

For example, a recent report published in April by the Government Accountability Office disputed NNSA’s claim that its long-term plans to sustain and rebuild U.S. nuclear warheads and their supporting infrastructure are affordable, calling this conclusion “optimistic.”

The costs of the nuclear upgrade plans will grow significantly between the Trump administration's first and final budget submissions.

The question is: will sufficient defense budget increases to accommodate this growth be forthcoming? Trump has called for rebuilding America's military and his calls for a bigger Navy and Army, among other proposals, would require significant spending beyond what is already planned.

While the total national defense budget request of $603 billion is $54 billion above the 2011 Budget Control Act caps in effect for FY 2018 and $19 billion above what was planned in Obama’s final budget, the increase does not include the defense buildup pledged by Trump.

In fact, the request would actually decrease defense spending by $3 billion over the next five years.

It's true that the five-year plan outlined in FY 2018 budget request is largely a placeholder and is likely to change after the Pentagon completes the various defense reviews it is undertaking. Congress could also try to add money above the request.

Yet though defense spending might see a boost during the Trump administration, it's unlikely to be as high as many people think. In any event, the proposed nuclear recapitalization effort is not a one, two, or three-year effort. It will require at least 15 years of sustained increased spending. Pressure on the defense budget, and the trade-offs such pressure will require, is likely to persist.

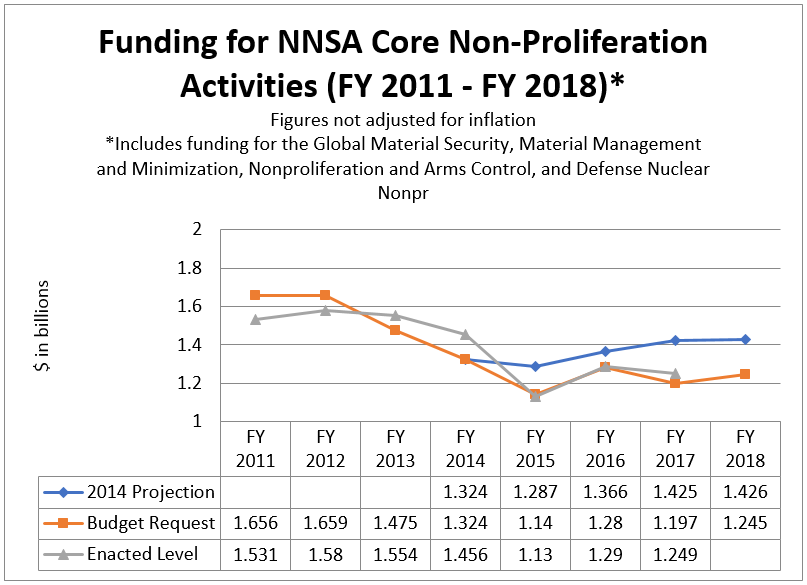

Indeed, the opportunity costs of spending on nuclear weapons are already starkly evident in NNSA’s budget request. While the submission for nuclear weapons is roughly $570 billion more than projected in FY 2017, the proposal for core nuclear terrorism prevention and nonproliferation programs is more than $200 million less than projected. This continues a trend of declining budgets for these programs, though in the Obama administration's defense it placed a high political priority on nuclear security (as evidenced by its leadership of the Nuclear Security Summitt process). There are no indications that the Trump administration plans to do the same.

“All-or-Nothing” Is a False Choice

Moving forward, the Trump administration must seriously examine options to reshape and rescale the plans and adequately fund a smaller number of projects that would still leave the United States with a capable and credible deterrent. Such options exist.

By contrast, if the Trump administration decides to accelerate or expand the scope of the nuclear weapons replacement and upgrade effort, it won't strengthen deterrence against Russia or China, but will put ever greater strain on the budget and generate significant controversy in Congress.

FY 2018 Budget Request for Defense Department Replacement Nuclear Delivery Systems and Energy Department Nuclear Weapons Activities

|

Program |

FY 2017 appropriation |

FY 2018 projection (as of FY 2017 request) |

FY 2018 request (+/- relative to FY 2017 approp) |

Program Description/Cost |

|

|

Columbia Class |

$1.86 billion |

$1.93 billion |

$1.88 billion (+$20 million) |

Would replace the current fleet of 14 Ohio class submarines with 12 new submarines. The first new submarine is scheduled to enter service in 2031. The funding request includes $1.04 billion in research and development and $843 million in advance procurement funding. The Pentagon earlier this year estimated the acquisition cost of the program at $128 billion (in then-year dollars). |

|

|

B-21 “Raider” |

$1.34 billion |

$2.17 billion |

$2 billion (+$660 million) |

Would eventually replace the B-52 and B-1 bombers. The current plan is to procure at least 100 new bombers that would begin to enter service in the late-2020s. A nuclear capability is planned for the new bomber but certification is not planned until two years after initial operating capability. The Air Force has refused to release the value of the EMD contract awarded to Northrop Grumman Corp. in October 2015 to develop the B-21 citing classification concerns. Independent experts put the total acquisition cost of the program at north of $110 billion. The Congressional Budget Office attributes 25% of the development cost of the program to the nuclear mission. |

|

|

Ground Based Strategic Deterrent |

$113.9 million |

$293.96 million |

$215.7 million (+$101.8 million) |

Would design, develop, produce, and deploy a replacement for the current Minuteman III ICBM system and its supporting infrastructure. GBSD is slated for initial fielding in FY28. The Air Force is planning to procure 666 GBSD and modernize the supporting Minuteman III infrastructure at an estimated acquisition cost $85 billion (in then-year dollars) over 30 years., though DoD CAPE believes the cost could be as high as $140 billion. |

|

|

Long-Range Standoff Weapon |

$95.6. million |

$419.82 million |

$489.3 million (+$393.7 million) |

Would develop a replacement for the nuclear-capable AGM-86B air launched cruise missile (ALCM). The new missile will be compatible with the B-2 and B-52 bombers, as well as the planned B-21 “Raider.” The first missile is slated to be produced in 2026. The current Air Force procurement plan calls for about 1,000 new missiles, roughly double the size of the existing fleet. The Air Force estimates the program will cost $10.8 billion (in then-year dollars) to acquire. The request includes $38 billion in MilCon funding. |

|

|

Nuclear Capability for F-35A Joint Strike Fighter |

$25.7 million |

$27.73 million |

$35.12 million (+$9.4 million) |

Would allow the Air Force to retain and forward deploy a dual-capable fighter aircraft, a role currently filled by the F-15E and F-16 in support of NATO commitments. The Air Force plans to provide Block 4A and Block 4B versions of the F-35A with the ability to carry the B61 mod 12 by 2022. CBO estimates that it would cost about $350 million to finish developing the modifications to make the F-35 nuclear-capable. This does not include the costs for implementing those modifications, the plan for which is still being developed. |

|

|

B61 Life Extension Program (tail kit) |

$137.9 million |

$296.4 million |

$179.5 million (+$41.6 million) |

Would provide the B61 mod 12 (a life extension program overseen by NNSA, with a new guided tail kit that would increase the accuracy of the weapon. The Air Force is currently planning to procure over 800 tail kits. The program also supports integration of the mod 12 on existing long-range bombers and short-range fighter aircraft. The Air Force estimates the tail kit will cost $1.6 billion to develop. A 2013 Pentagon report put the total life-cycle cost for the program at $3.7 billion. |

|

|

NNSA Weapons Activities |

$9.25 billion |

$9.67 billion |

$10.24 billion (+$994 million) |

Maintains and enhances the safety, security and reliability of the U.S. nuclear warhead stockpile and its supporting infrastructure. The request is an increase of roughly $580 million above the level projected for FY 2018 in Obama’s final FY 2017 budget submission. The request includes higher than projected increases for life extension programs, deferred maintenance of aging facilities, tritium sustainment, and contractor pensions. |

|

|

-B61 mod 12 LEP |

$616.1 million |

$727.2 million |

$788.6 million (+$172.5 million) |

Would refurbished the aging B61 nuclear gravity bomb by consolidating four of the five existing versions of the bomb into a single weapon known as the B61-12. The first bomb is slated to be produced in 2020. The upgraded weapon will be equipped with a new tail-kit guidance assembly (see above). NNSA estimates the cost of the LEP at $7.6 billion but the agency’s independent cost estimate thinks the cost will be $10 billion.

|

|

|

-W80-4 LEP |

$220.3 million |

$462.2 million |

$399.1 million (+$178.8 million) |

Would refurbish the aging ALCM warhead for delivery on the LRSO (see above). NNSA estimates the cost of the program will be between $7.4-9.9 billion (in then-year dollars). The first refurnished warhead is scheduled for production in 2025.

|

|